Philadelphia Public Parks

Essay

Philadelphia boasts the oldest and one of the largest urban park systems in the United States, comprising more than one hundred parks encompassing some ten thousand acres. With origins in William Penn’s innovative city plan, Philadelphia’s public green spaces range in size and type from small neighborhood squares to extensive watershed and estuary parks along the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers and their tributaries. Central to the evolution of the city proper, these spaces have served over time as an indispensable resource to the Greater Philadelphia region.

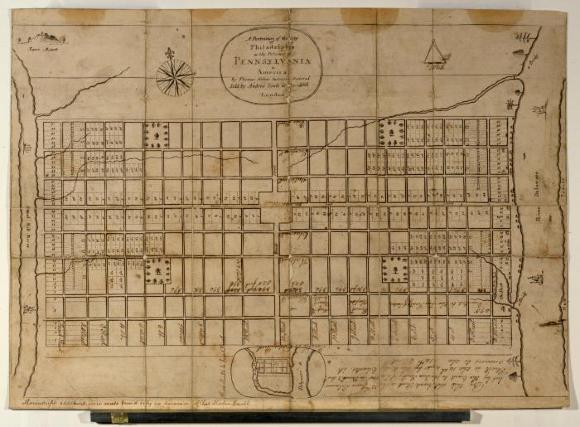

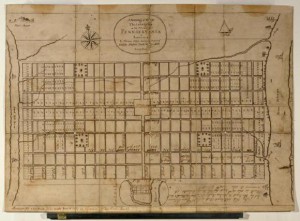

Penn’s Squares

In their 1682 “Portraiture” of Philadelphia, William Penn (1644-1718) and Surveyor-General Thomas Holme (1624-95) laid out a two-square-mile street grid in quadrants, with a ten-acre center square reserved for public buildings and four surrounding eight-acre public squares, modeled after the popular London park called Moorfields. Penn intended that Philadelphia’s city government would landscape and administer the squares, but because he neglected to transfer title to the city no efforts were made to develop them. As a result, the squares lay vacant or were used for pasture, trash dumps, and potter’s fields for more than a century.

Philadelphia’s first true public park was created on the grounds of the State House, when Samuel Vaughan (1720-1802), a merchant and member of the American Philosophical Society, laid out walkways lined with elm saplings in double rows there in 1784. After the state and federal governments departed in 1799 and 1800 respectively, municipal offices moved into the State House and, after resisting efforts by the state to open streets through the grounds, the city purchased the site in 1816 and renovated the gardens.

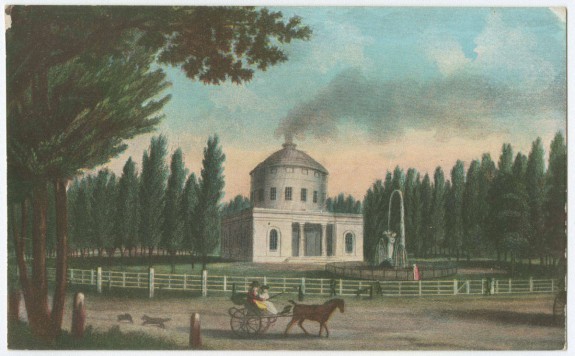

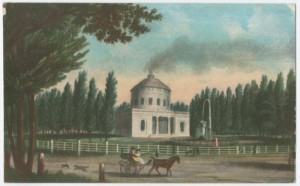

Because the 1779 Divesting Act had transferred proprietary properties to the state, including Penn’s squares, Philadelphians feared that the legislature might cut streets through these spaces. Efforts to improve public health proved effective in the city’s efforts to gain control of the squares, however. In 1799, in response to devastating yellow fever epidemics, city councils established a municipally-run water distribution system, managed by an appointed watering committee charged with overseeing the delivery of water pumped from the Schuylkill River to homes and businesses. Benjamin Latrobe (1764-1820) designed the main pumping station that was erected at the center square. When lawns and Lombardy poplars were planted in the square and a fountain installed, this became a popular gathering place and residents petitioned for upgrades to the other squares so they could be used as recreational spaces. Believing that tree plantings would also purify the atmosphere, the city undertook landscaping in the eastern squares by the 1820s, and in 1825 city councils formally renamed the five original squares—Penn (center), Washington (southeast), Franklin (northeast), Rittenhouse (southwest) and Logan (northwest). The city block containing the State House and its adjacent garden were renamed Independence Square. Improvements at the western squares were underway by the 1840s, as residential development proceeded to the Schuylkill and beyond.

Fairmount and the Schuylkill Park

Larger parks also evolved from the city’s innovative municipal water distribution system. When Latrobe’s Centre Square pumphouse proved inadequate, the Watering Committee built a larger and more efficient pumping facility at the base of a reservoir excavated atop the hill called Fairmount just north of the center city limits. The waterworks began operating in 1815. In scale and style, the elegant neoclassical waterworks, designed by Frederick Graff (1775-1847), echoed the private villas lining the nearby river built by wealthy Philadelphians in the previous century. Tourists flocked to Fairmount to stroll through gardens and walkways laid out around the water works and to admire the view from the reservoir of the picturesque Schuylkill district.

But the innovative water delivery system also fueled a burgeoning industrial economy. Mills and factories were built along the Schuylkill River and the Wissahickon Creek from Manayunk and Roxborough northward. Industrial wastes were dumped into waterways, as well as sewage produced in the growing communities. But a semi-rural zone separated the center city from these industrializing riverside towns because many of the eighteenth-century Schuylkill estates remained in private hands. By the 1840s, Philadelphians had begun to lobby the city to acquire these properties for use as public parks so as to create a buffer to protect the water supply. Advocates reasoned that because the city had purchased property at Fairmount (outside the city limits) for the municipal waterworks, the city should be able to purchase additional properties thereabouts. When the Lemon Hill estate was put up for sale, Quaker merchant and Watering Committee member Thomas Cope (1768-1854) led a campaign to secure its purchase, which was finalized in 1844.

Faced with the onward march of development in the center city and the surrounding county, Philadelphia’s social reformers envisioned public parks as the “lungs” of the city, believing that they refreshed the health of city dwellers by providing opportunities to commune with nature. Parks could improve the mind as well as the body, an 1851 editorial in the North American declared, by providing “an uncorrupted atmosphere” and places “where we can sometimes turn the sickened eye from the red glare of man’s habitations to the softened hues of bountiful nature.”

City-County Consolidation, 1854

By the mid-nineteenth century, Penn’s public squares were too small to accomplish these ends. Consolidation of the city with the county in 1854 aimed to solve that problem by directing city government to create more public parks, but it did not specify where those spaces should be located or how they would be funded or administered. Some residents advocated a network of small neighborhood parks, following the model of Penn’s squares. Others lobbied for larger properties, as in 1856 when a group of investors led by John Jay Smith (1798-1881) purchased a forty-five-acre tract in the north of the city, renamed it Hunting Park, and hired landscape gardeners to develop the site as a public park.

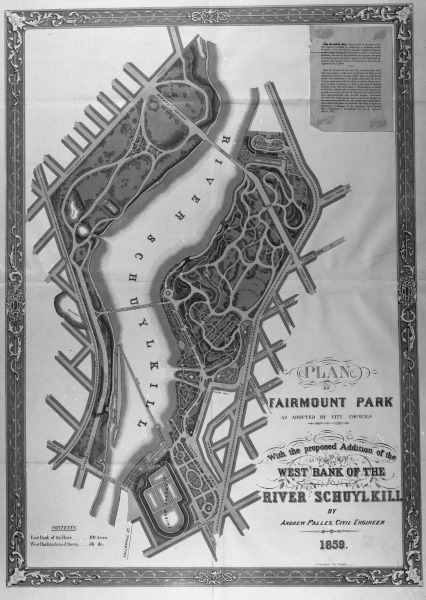

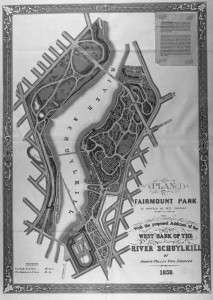

The enlargement of parks along the Schuylkill, both for recreation and to protect the river, accelerated with consolidation, and in 1855 the city dedicated Lemon Hill as “Fairmount Park.” Two years later, the city acquired the adjoining Sedgeley estate and commissioned James C. Sidney (c. 1819-1881) and Andrew Adams (c. 1800-1860) to relandscape the conjoined properties, although work on this project was suspended in the mid-1860s in response to calls to create a much larger park along both sides of the Schuylkill. Park advocates emphasized the economic and cultural benefits of a large “central” park. It could provide some sense of spatial unity within the sprawling metropolis, similar to New York’s Central Park, and, as in New York, they argued, the park would raise real estate values in surrounding neighborhoods. After the state expanded the city’s power of eminent domain, park supporters in the business community pushed ahead to add hundreds of acres along both banks of the Schuylkill by donating properties and by lobbying for further state legislation in support of expropriating more properties along the Schuylkill to extend the park.

That legislation was enacted in 1867, when the Pennsylvania legislature passed an Act of Assembly creating the sixteen-member Fairmount Park Commission (FPC) with authority to acquire land along the east and west banks of the Schuylkill, “for the health and enjoyment of the people of said city, and the preservation of the purity of the water supply.” In 1868, a second act doubled the East and West Schuylkill parks north to East Falls and added a new park in the Wissahickon Valley. The Wissahickon Creek was a popular recreational destination celebrated for its picturesque scenery by such writers as Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) and George Lippard (1822-1854). But like the Schuylkill, it was also a major industrial waterway. By expropriating land along the creek and closing down the mills, the FPC hoped to expand the pollution buffer and diversify the park landscapes by adding the Wissahickon’s steep bluffs and forests to compleiment the dells and rolling meadows of the Schuylkill properties.

Fairmount Park’s Incremental Development

In contrast to New York’s Central Park or Prospect Park in Brooklyn, where designers were hired to prepare comprehensive plans to reconfigure topography and plantings within a defined precinct, the FPC developed Fairmount Park incrementally and opportunistically. This history of land acquisition set the pattern for growth within Philadelphia’s evolving park system. Although the FPC consulted landscape architects about reconfiguring park properties, it ultimately decided to make minimal changes, both to save expense and to protect the “scenic contours” of the historic river estates as well as to preserve the eighteenth-century houses so as to enshrine the memory of Philadelphia’s colonial grandeur. While the FPC drew on appropriations from the city to compensate landowners whose properties were expropriated, the city was unwilling to finance comprehensive landscape improvements.

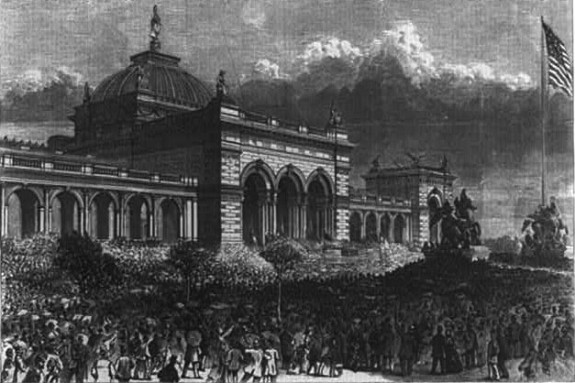

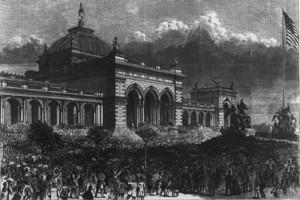

Subscribing to Andrew Jackson Downing’s (1815-52) vision of public parks as appropriate sites for cultural institutions, the FPC facilitated the establishment of major civic institutions and organizations. To that end, the Fairmount Park Art Association was formed in 1871 to commission works of public sculpture throughout the city; the first of these commissions were erected in Fairmount Park. Three years later, the Philadelphia Zoo opened on the grounds of The Solitude, formerly the estate of John Penn (1760-1834), one of William Penn’s grandsons. Funding for the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, held on a four-hundred-acre site in West Park, enabled the FPC to make much-needed infrastructure improvements. Memorial Hall, one of two permanent buildings erected for the Centennial, became the home of the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art that opened in 1877. A second permanent building was Horticulture Hall, operated by the FPC as a public conservatory.

The FPC’s willingness to accommodate the Centennial Exhibition reveals how Fairmount Park differed significantly from contemporary parks created in other American cities by landscape architects. These places were methodically laid out and planted so as to create a choreographed landscape experience. As integrated designs, these parks could not accommodate significant intrusions such as new roadways or buildings. Frederick Law Olmsted, for example, discouraged museums and zoos in his parks. The FPC pursued a more laissez-faire policy. The absence of a comprehensive design meant that roads or buildings could be added as needed. This approach also extended to recreation. Olmsted required that recreation be permitted only in designated areas because his parks were newly invented works of art. Fairmount Park was not a new creation nor did it introduce new recreational areas. On the contrary, the city and then the FPC simply assumed control of spaces that had been used informally for recreation for many decades.

Neighborhood Parks and Watersheds

Despite limited appropriations, the FPC continued to acquire acreage, and by 1900 Fairmount Park (the East and West Parks and the Wissahickon) encompassed just under three thousand acres. Tens of thousands of residents visited the park areas annually for boating and team sports, to hike or ride along the Wissahickon paths, or to visit the zoo, the Pennsylvania Museum, or Horticultural Hall. Yet many members of city government questioned whether the park was too large and too expensive to maintain. Residents of the city’s eastern, northeastern, and southern neighborhoods also complained that the parks were “as inaccessible as the forests of the Alleghenies,” prompting the FPC to partner with transit companies to lay out streetcar lines to and within East and West parks.

Concerns about access revived the campaign for smaller neighborhood parks dispersed throughout the city. Beginning in the 1880s, city councils partnered with the newly-created City Parks Association (CPA), a voluntary organization, to acquire properties that would be administered by the Department of Public Works independently of the FPC. These included League Island, Bartram’s Garden, and Stenton (the house and adjoining property), as well as new playgrounds. Additional acreage, such as the Burholme estate in the northeast section of Philadelphia, came through private donations. Inspired by urban planning approaches promoted during the City Beautiful era, the CPA and city government envisioned an integrated network of parks, encompassing the Cobb’s Creek, Pennypack Creek, and Tacony Creek watersheds that would be linked by parkways. Unlike the opportunistically assembled and managed Fairmount Park, landscape designers were involved in reconfiguring and improving many of these areas, as in 1912, when the Olmsted Brothers firm was commissioned to design League Island Park in south Philadelphia. Portions of this park were later used for the 1926 Sesquicentennial Exposition, and the park was later renamed for Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

By the 1920s, the administration of Philadelphia’s public parks had split between two separate entities. The Bureau of Recreation, a city agency, administered many of the small parks and playgrounds developed with the CPA. The semiautonomous FPC had enlarged its purview by gaining control of the watershed parks, as well as many smaller parks, notably Penn’s original squares. It was the FPC that implemented many of the projected parkways, such as cutting a diagonal avenue through the center city street grid from Penn Square to Fairmount to link the Schuylkill parks to the center city. When completed in 1918, the Benjamin Franklin Parkway also opened access to the city’s northwest districts from Center City. The FPC also continued the development of watershed parks along Cobb’s Creek, Pennypack Creek, Tacony Creek as well as Poquessing Creek, and opened new parkways to those areas. Roosevelt Boulevard, also completed in 1918, opened up the greater northeast to residential development by linking Hunting Park to the Tacony and Pennypack. Because of the FPC’s leadership, Philadelphia’s park system as a whole came to be referred to as the “Fairmount Park system.”

A Complicated Park System

Philadelphia’s parks may have been among the nation’s most extensive in the early twentieth century, but the opportunistic approach to park building produced an ad hoc system that left many Philadelphians farther than a ten-minute walk from any public green space. As industry in the region declined and Philadelphia’s tax base shrank, park appropriations—never generous—decreased. Divided administration between the Recreation Department and the FPC—which survived the 1951 implementation of the Home Rule Charter—also complicated matters. Under new rules, city politicians were more likely to seek funding for a recreation center or playground in their respective districts than to finance the improvement or maintenance of parks or historic houses administered by the court-appointed FPC, many of whose members were drawn from the ranks of the social and business elite. In 1960, appropriations for parks made up 2.26 percent of the general operating budget. By 1980, appropriations had declined to 0.71 percent, forcing the park commissioners to make deep cuts in staffing and operations. By 2009, appropriations amounted to only 0.32 percent of the municipal operating budget.

After World War II, the FPC had a mixed record of protecting parks and watersheds from development. The commissioners failed to prevent construction of the Schuylkill Expressway (I-76) through the West Park, though this project was facilitated by the fact that railroads already traversed many sections of the park and an alternate route farther to the west would have been more expansive and controversial because it entailed demolishing residential neighborhoods. A notable success was the defeat of attempts to build the Pulaski Expressway (Pa. Route A 90) through the Tacony and Pennypack watersheds.

During the postwar period, the federal government became involved in Philadelphia’s public parks after Congress authorized the creation of Independence National Historical Park, administered by the National Park Service. As formally established in 1956, the park encompassed more than forty acres around Independence Hall and included such landmarks as Carpenters’ Hall, the American Philosophical Society, First Bank of the United States, Second Bank of the United States, Mikveh Israel Cemetery, and Independence Mall.

First Comprehensive Master Plan

In the 1970s and 1980s, the FPC spearheaded a number of conservation and preservation initiatives. In 1983, it initiated the first comprehensive master plan to define strategies for conservation as well as policies and guidelines for land acquisition, finance, and administration in the park system through the year 2000. This plan in turn informed the grant-funded Natural Lands Restoration and Environmental Education Program, begun in 1996 to restore the natural areas in seven watershed and estuary parks throughout the city (FDR Park, Cobbs Creek, Fairmount [East and West Parks], Tacony Creek, Pennypack, Poquessing Creek, and the Wissahickon Valley), and build a constituency for the park’s protection through environmental education and public stewardship.

By the late 1990s, the FPC’s effectiveness was in rapid decline. Perceived redundancies with the Department of Recreation, which managed recreational facilities and historic houses as well as parks, prompted cuts in municipal funding. It did not help the FPC that it had been criticized for many years for a lack of transparency and accountability in policy-making decisions and for insufficient park management expertise. A city proposal to generate revenue by leasing parklands to private entities further stymied the commission as its members divided over the advisability (and legality) of the proposal. In a 2008 referendum, Philadelphians voted to abolish the FPC. The Home Rule Charter was duly amended to create a new combined Parks & Recreation Department (PPR), led by a commissioner appointed by the mayor, who would work with an advisory Commission on Parks and Recreation, appointed by City Council, to draft and implement policies and standards governing the use of Philadelphia’s parks and recreational facilities.

PPR subsequently undertook management of the city’s parks system within a comprehensive and holistic model for urban sustainability throughout all park areas. The Philadelphia Trail Master Plan, completed in 2011, was developed in cooperation with the City Planning Commission. As part of GreenWorks Philadelphia, launched in 2009, PPR expanded green space acquisitions and upgraded points of access. PPR also partnered with the Philadelphia Water Department, the Philadelphia School District, and the Trust for Public Lands to upgrade infrastructure maintenance, in particular by improving storm water and forest management.

Importance of Public-Private Partnerships

Even before the demise of the FPC, Philadelphia’s parks relied heavily on public-private partnerships to fund capital projects, park stewardship, and programming. Volunteer groups, such as the Friends of the Wissahickon, long played an important role in caring for individual parks, though the financial and logistical resources available to these groups varied widely. The Philadelphia Parks Alliance, an independent advocacy group, formed in 1985 to monitor public policies as well as best practices in parks management and to generate public support for parks and recreation in Philadelphia. The Fairmount Park Conservancy, founded in 2001, took a leading role in several projects such as the revitalization of Hunting Park and Penn Treaty Park and participated in master planning for the East and West Parks. PPR also worked with both the Schuylkill River Development Corporation and the Delaware River City Corporation to revitalize the banks of Philadelphia’s major rivers, most notably with the Schuylkill River Trail, a system of multiuse boardwalks, bike paths, and trails along the length of the Schuylkill, and the establishment of Lardner’s Point Park that link the city and its parks with the surrounding region.

Evolving from William Penn’s innovative vision, Philadelphia’s parks grew first as the result of community activism and then expanded through well-intentioned paternalism. The fate of the city’s parks lies with public-private partnerships that bring elected politicians, municipal managers, and community groups together as equals to identify shared goals, identify viable funding sources, and thereby to plan strategically for the future.

Elizabeth Milroy is Professor and Department Head of Art & Art History at the Antoinette Westphal College of Media Arts & Design, Drexel University. She is the author of The Grid and the River: Philadelphia’s Green Places, 1682-1876 (2016). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Association for Public Art (formerly the Fairmount Park Art Association)

- City of Philadelphia Parks and Recreation

- Fairmount Park Conservancy

- Historic Houses administered by the Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Philadelphia Parks Alliance

- Urban Parks in the United States (Exhibit, Digital Public Library of America)

- The Rail Park

- Friends of Matthias Baldwin Park