Woman Suffrage

Essay

While the Philadelphia region often led the way on progressive reforms, by the twentieth century, woman suffrage was not among them. The region boasted a number of early woman suffrage advocates, and women in New Jersey had the right to vote during the early years of the republic, but by the late nineteenth century, Pennsylvania in particular lagged behind other states in granting women even limited voting rights. Twentieth-century efforts to pass referenda in support of equal suffrage in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware all failed. Throughout, divisions over strategy and among women across racial, economic, and social lines complicated the struggle. After Congress finally sent a federal amendment to the states in 1919, Pennsylvania ratified quickly, but Delaware’s vote against the amendment allowed Tennessee to become the final state needed to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment on August 18, 1920.

Earlier history had been more promising. In the years after independence, New Jersey alone granted women the right to vote, under the terms of the 1776 state constitution and confirmed by legislation passed in the 1790s. The provision, the result of partisan jockeying for voter advantage, applied only to women (and men) of sufficient property. Since few owned property in their own right, few actually voted. As a result, when the legislature rescinded that right in 1807 and limited suffrage to white males—an act of questionable legality since it overturned a constitutional provision with a legislative act—women did not fight disenfranchisement. In New Jersey and elsewhere, the gradual expansion of suffrage to all white men in the early nineteenth century was accompanied by the curtailing of voting rights for women and African Americans.

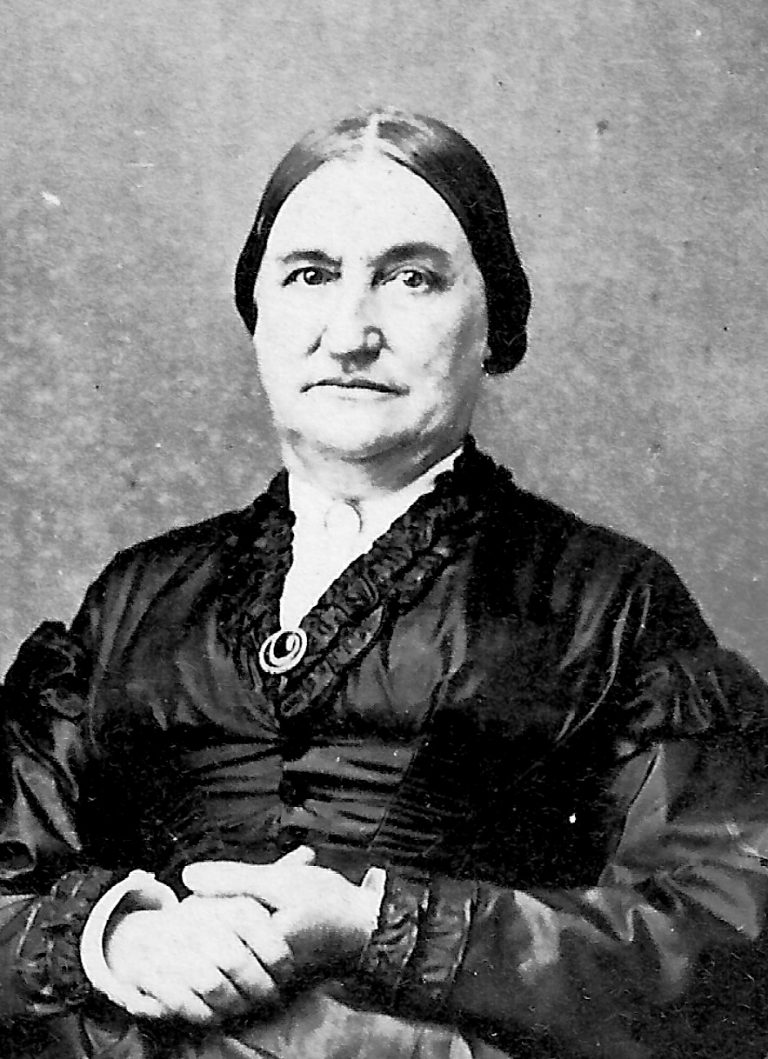

The early woman’s rights movement was closely tied to the abolition movement, with Quakers taking a leading role in the Philadelphia region. Formal agitation for the vote began when several men in Burlington County, New Jersey, unsuccessfully petitioned the state constitutional convention in 1844 to reinstate women’s right to vote. In 1852, Quaker women organized Pennsylvania’s first woman’s rights convention, at Horticultural Hall in West Chester, presided over by abolitionists Lucretia Mott (1793–1880) and Mary Ann White Johnson (1808–72). Mott and Sarah Pugh (1800–84) founded the interracial Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and organized the fifth national woman’s rights convention, held in Philadelphia’s Sansom Street Hall in October 1854. These conventions advocated not only for woman suffrage, but for woman’s rights.

Embracing Other Issues

During and following the Civil War, suffrage advocates turned their attention to emancipation and African American rights. In 1866, woman’s rights activists organized the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) to “secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex.” Lucretia Mott served as president. Philadelphia abolitionists and woman’s rights supporters formed the affiliated Pennsylvania Equal Rights Association in January 1867. Its founder, Robert Purvis (1810–98), who had been the first African American member of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society and a former president of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, was the only Black male abolitionist to support the idea that Black men should not be granted the vote until all women were also enfranchised. In December 1866, suffragists in the reform-minded community of Vineland, in Cumberland County, New Jersey, organized the Vineland Equal Rights Association and sent a petition to the Republican state convention for “Impartial Suffrage, irrespective of Sex or Color.”

In 1869, the AERA splintered over support of the Fifteenth Amendment, which granted African American men, but not women, the right to vote. Those who believed that Black men should not receive the vote until women did as well formed the new National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902) and Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906). Those who believed that this was the “Negro’s hour” formed the American Woman Suffrage Society (AWSA), led by Lucy Stone (1818–93) and Henry Blackwell (1825–1909) of New Jersey.

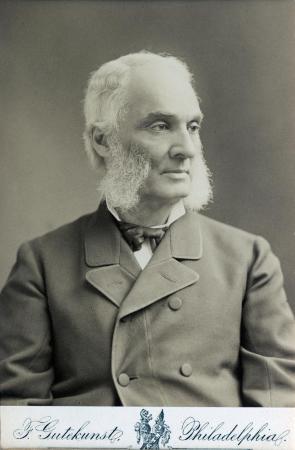

In the Philadelphia region, a number of new suffrage groups affiliated with one of these two societies. The New Jersey Woman Suffrage Society, organized in Vineland in November 1867 and led by Stone and Blackwell, which had drawn most of its early members from southern New Jersey, shifted to ally with the AWSA in 1869. More women from the northern counties became active, while the suffragists of Vineland turned to their own organization and tactics. The Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association, formed at Philadelphia’s Mercantile Hall in December 1869 and led by abolitionist Mary Grew (1813–96), also aligned with the AWSA. This society, active into the twentieth century, primarily engaged in educational activities. In March 1872, Philadelphia suffragists sympathetic to the NWSA organized the competing Citizens’ Suffrage Association at 333 Walnut Street, the office of its president, Edward M. Davis (1811–87), son-in-law of Lucretia Mott. Meanwhile, suffragists in Delaware, a border state, remained unorganized, although they held their first convention in 1868.

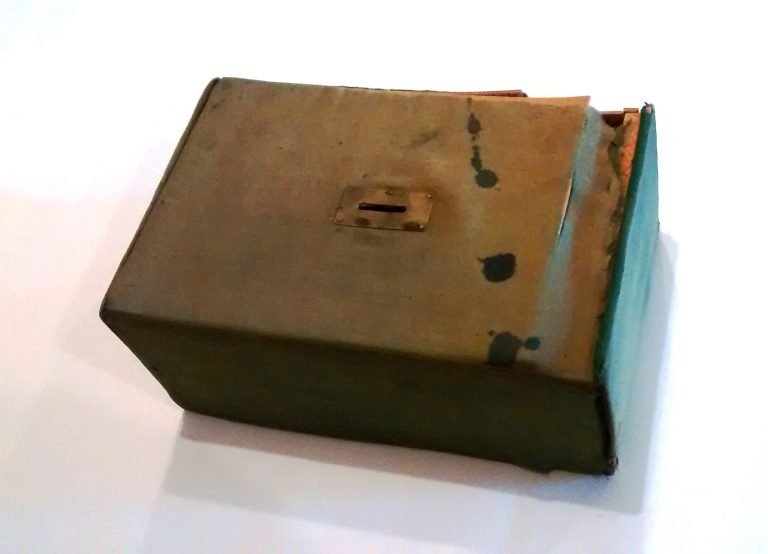

In March 1868, Portia K. Gage (1813–1903) of Vineland attempted to vote in the municipal elections but was prevented because she was not registered. That fall she returned with 171 other women, Black and white, and their own ballot box, and voted. The Vineland women continued the practice in 1869 and 1870. Their actions inspired women around the country to begin going to the polls to test the theory that women, as citizens, were enfranchised by the Fourteenth Amendment, suffrage being one of citizenship’s “privileges and immunities.” Carrie S. Burnham (1838–1909), a member of the Citizens’ Suffrage Association of Philadelphia, attempted to vote in October 1871. After a court ruled against her, she appealed to the state supreme court and also spoke before the state legislature. Burnham lost her appeal. In 1875, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Minor v. Happersett, ruled that voting was not a right of citizenship.

State Constitutions

After ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, suffragists also worked to change voting clauses in state constitutions, many of which were rewritten in the Reconstruction era. Women sought to have the word “male” removed from voter qualifications at the same time that states removed the word “white.” The Pennsylvania constitutional convention of 1872–73, however, changed its description of those eligible to vote from “white freeman” to “male citizens.” The new constitution did allow women to run—but not vote—for school offices. Neither New Jersey nor Delaware updated their constitutions.

In 1876, at the instigation of the Philadelphia Citizens’ Suffrage Association, NWSA determined to use the centennial celebration of American Independence, in Philadelphia, to point out the contradiction between the ideals of the Revolution and the reality of restricted suffrage. It also began lobbying for a sixteenth amendment for woman suffrage. As early as May 1875, Susan B. Anthony rented rooms at 1431 Chestnut Street to serve as headquarters. That fall, the leaders of NWSA began planning a Declaration of Rights of the Women of the United States, which they intended to read at Independence Hall on July 4. Denied permission to present their declaration at the event, they obtained tickets to it, and, after a reading of the Declaration of Independence, distributed it to the audience while Susan B. Anthony led a delegation onto the stage and handed it to the presiding officer. The AWSA, which had declined to sign the declaration, held its own meeting on July 3 at Horticultural Hall to recognize the centennial of woman suffrage in New Jersey and protest its loss in 1807.

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) became an important ally of the suffrage movement in the late nineteenth century. In Montgomery County, the WCTU shared space with the local suffrage society in Norristown. The New Jersey WCTU began cooperating with the New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association by 1884. In Delaware, the state WCTU organized a suffrage department in 1888, and Martha S. Cranston (1845–1926) became its superintendent in 1889. The issues of temperance and prohibition complicated arguments for woman suffrage, particularly in Philadelphia, into the final years of the suffrage campaign.

Meanwhile, in 1887, Congress defeated a woman suffrage amendment. This blow led suffragists at the national level to once again reassess strategy. For this and other reasons, the rival NWSA and AWSA reorganized in 1890 as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), with Anthony as its first president. State societies coordinated with this new national society. In 1892, Lucretia Longshore Blankenburg (1845–1937) became president of the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Society and encouraged the formation of local societies. Jane Campbell (1845–1928) founded the Woman Suffrage Society of Philadelphia that year and served as its president for nearly twenty years. The New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association also reorganized in 1890. Slow to organize, Delaware’s first suffrage society, the Wilmington Equal Suffrage Club, formed in November 1895, under the leadership of Philadelphia’s Rachel Foster Avery (1858–1919), a member of the Citizens’ Suffrage Association and leader of NWSA’s effort to organize Pennsylvania. A state suffrage society formed in 1896, with temperance advocate Martha Cranston as president.

Piecemeal Progress

In the 1890s, some suffragists focused on securing more limited voting rights. New Jersey suffragists, working with the WCTU and the Grange, lobbied for an amendment to restore (for rural women) and expand (for others) women’s right to vote for school commissioners; voters defeated the amendment in a special election in 1897. Suffrage activists were particularly interested in Delaware because it had a state constitutional convention scheduled for 1897. They were unsuccessful in getting “male” struck as a voting qualification, but Delaware did pass a law in 1898 that allowed tax-paying women to vote for school trustees.

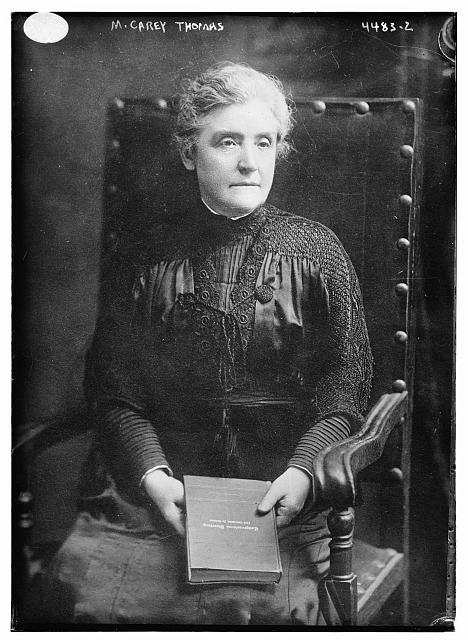

Philadelphia experienced a proliferation of local suffrage societies representing different constituencies and strategies in the early twentieth century. Among them were the Pennsylvania College Equal Suffrage League (1908), an affiliate of the National College Equal Suffrage League, led by M. Carey Thomas (1857–1935), president of Bryn Mawr College; the Pennsylvania Limited Suffrage League (1909), which, as its name implied, advocated for a limited suffrage, excluding illiterates and criminals; and the Equal Franchise Society of Philadelphia (1909), which drew its members from Philadelphia’s society women. In 1909 the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association also formed a state Woman Suffrage Party to work on the state legislature in Harrisburg, following the plan put forth by NAWSA’s Carrie Chapman Catt (1859–1947). In New Jersey, however, the defeat of 1897 had stymied state efforts for a time; by 1908 no branches of the state suffrage society were active in the southern counties. Delaware suffragists experienced similar difficulties after their 1897 defeat.

The new energy that infused the woman suffrage movement in the region, and nationally, stemmed from a new generation of leaders. Inspired by suffragists in England, where she had spent a few years after college, Alice Paul (1885–1977), a young Quaker woman from Mount Laurel, New Jersey, and graduate of Swarthmore College and the University of Pennsylvania, advocated the use of rallies, parades, and similar tactics to draw public attention to the cause. She also pushed NAWSA to focus on the goal of a federal amendment rather than its state-by-state campaign. By 1913, Paul had formed the Congressional Union (CU), which originally affiliated with NAWSA but soon broke with it over strategy.

Alice Paul

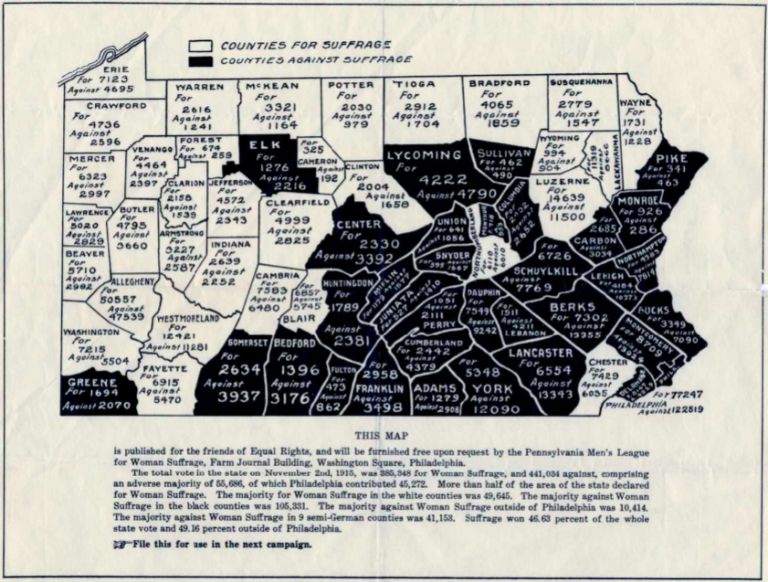

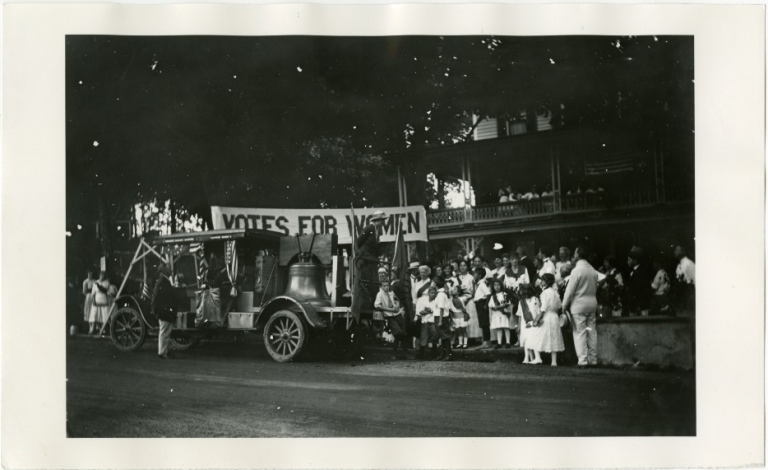

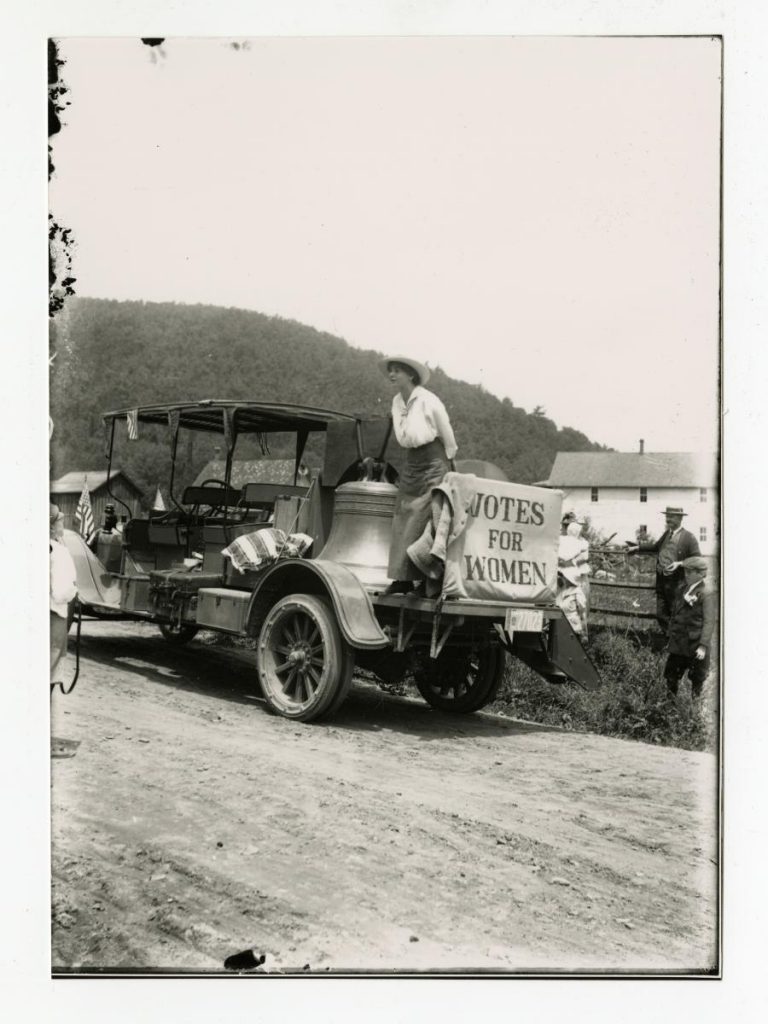

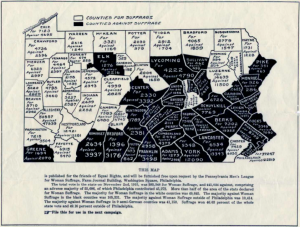

The new CU appealed to many Philadelphia suffragists. Leadership of the state suffrage society shifted to the western part of the state, where its emphasis on smaller meetings and less public spectacle was more effective. But Philadelphia became Alice Paul’s testing ground for new tactics that she later took to a national stage. In May 1914, Paul planned May Day celebrations in every state. In Philadelphia, many of the city’s suffrage societies, including the Men’s League, held the state’s first suffrage demonstration in Rittenhouse Square before marching on Market Street to Washington Square. The CU and state society cooperated, sometimes uneasily, on a successful effort to secure a state referendum, which culminated in a statewide campaign in 1915. For the most part, the CU agreed not to interfere with the state society during that campaign, the highlight of which was a statewide tour of the Justice Bell, a replica of the Liberty Bell with its clapper silenced until women won the right to vote. Financed by Katharine Wentworth Ruschenberger (1853–1943) of Chester County, the Justice Bell ended its tour in Philadelphia in October with a parade before a crowd of one hundred thousand. The referendum did not pass, however, with Philadelphia and the counties in southeastern Pennsylvania—except for Chester County—voting against suffrage, in part due to Philadelphia’s machine politics and the power of the liquor interests in the region, which associated woman suffrage with the temperance cause.

New Jersey, too, voted on a suffrage referendum in 1915. The shifting political power in the state away from the Democratic Party gave suffragists cause for hope. NAWSA sent professional organizers to the state, including to Camden, where Jenney G. Kerlin (b. 1878) led the Camden Equal Suffrage League. The anti-suffrage forces were also well organized, however, and the political parties refused to take a stand. President Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924), former governor of New Jersey, endorsed the referendum, indicating that he thought the women of New Jersey should have the vote, but as a private citizen (thus avoiding a stand on a national amendment). But voters defeated the referendum by a wide margin; it lost in every county except Ocean Country, where it won by a very narrow margin.

Meanwhile, Paul’s supporters focused on a national amendment. In Philadelphia, she found strong allies in Caroline Katzenstein (1876–1968), active in the state suffrage society and the Equal Franchise League, and Dora Kelly Lewis (1862–1928), as well as Mary A. Burnham (1852–1928), a major donor to the National Woman’s Party, which grew out of the CU. While NAWSA suspended much of its work during World War I, the National Woman’s Party pressed on, lobbying representatives in Washington and holding vigils outside the White House to highlight President Wilson’s hypocrisy in fighting for democracy overseas while women were disenfranchised at home. Lewis was among those arrested during the protests in 1917, jailed, and force fed to end a hunger strike.

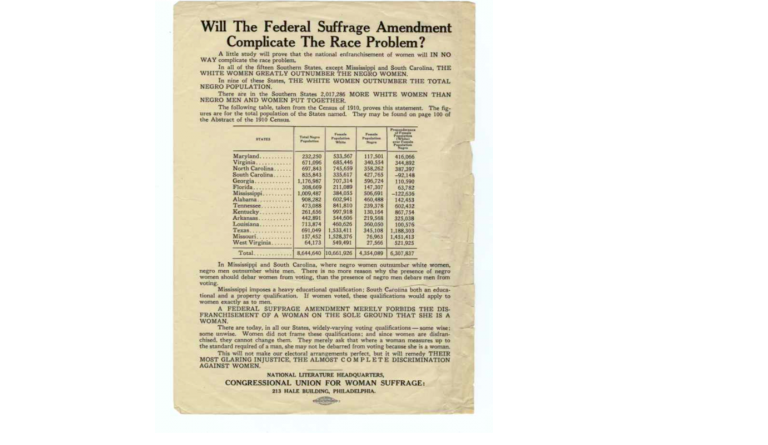

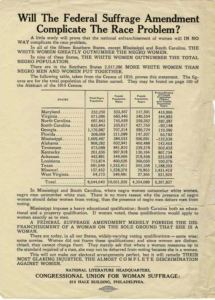

The long struggle with Congress finally ended when it passed a nineteenth amendment for woman suffrage on June 4, 1919. Suffragists in all states then turned their attention to achieving ratification in the required minimum of thirty-six states. Pennsylvania quickly ratified, on June 24. The struggle was more protracted in New Jersey and Delaware. In New Jersey, the legislature put off consideration until 1920, and suffragists worked to elect pro-suffrage representatives in the fall of 1919. After a closely contested vote, New Jersey’s legislature ratified the amendment on February 9, 1920. By the end of March, when thirty-five states had ratified, suffragists focused on a handful of states that had not yet rejected the amendment, including Delaware. As in many southern states, anti-suffrage activists exploited fears that the amendment would bring more Black voters to the polls, and the Delaware campaign ended in defeat on June 2. Tennessee became the thirty-sixth state to ratify on August 18, 1920. Delaware finally ratified the amendment on March 6, 1923.

The Justice Bell rang for the first time on September 25, 1920, on Independence Square in Philadelphia. Over one million women in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware voted in a national election for the first time on November 2, 1920. It had taken well over one hundred years for women to win that right and to push the nation forward toward living up to the ideals put forth at its founding.

Tamara Gaskell is Public Historian in Residence at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities and co-editor of The Public Historian. Previously, she was editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography and Pennsylvania Legacies, while director of publications at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and an assistant editor of the Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Portraits of American Abolitionists Collection Guide (Massachusetts Historical Society)

- For Stanton, All Women Were Not Created Equal (NPR)

- Old Friends Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Made History Together (NEH)

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton

- National American Women’s Suffrage Assocation (Harvard University)

- Woman Suffrage in New Jersey (Library of Congress)

- Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association (Cornell University Libraries)

- Women’s Suffrage Collection, 1912-1920 (Penn State Libraries)

- Commemorating the Justice Bell Tour (Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities)

- Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention of 1873 The Documents (Duquesne University Gumberg Library)

- Women’s Christian Temperance Union (University of Virginia)

- Jane Campbell Scrapbooks Finding Aid (University of Pennsylvania Libraries)

- Mill-Rae: A Monument of Women’s History Hidden in Plain Sight (Pennsylvania Historic Preservation Blog)

- In Somerton, Suffragists’ Vision Lives On (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Nineteenth Amendment in Delaware (Widener University Law Blog)

- Delaware Treated to Spectacle as Suffragists Tramp Across State (Reflections on Delmarva's Past)

- Women's Suffrage: Campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)

- In Her Own Right: Women asserting their civil rights, 1820-1920 (Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries)

- 19th Amendment and Women 's Access to the Vote Across America (National Park Service)

National History Day Resources

- Call for the First Anniversary of the American Equal Rights Association (Library of Congress)

- “On Account of Color or Sex”: A Historical Examination of the Split between Black Rights and Women’s Rights in the American Equal Rights Association, 1866-1869 (PDF, Indiana University of Pennsylvania)

- NWHM: "Three Generations Fighting for the Vote"-- Panel Discussion at George Washington University (National Women’s History Museum)

- Address of Sojourner Truth to the American Equal Rights Association First Anniversary (PBS)

- NWHM Suffrage Lesson Plan (National Women’s History Museum)

- New Equal Rights Association (Newseum)

- Projects From History 213: First Wave Feminism (Oberlin College)

- “Conflict, Consensus, and Conclusion,” Not for Ourselves Alone Classroom Guide (PBS)

- Memorial to Congress from the National American Women Suffrage Association (Library of Congress)