Women’s Education

By Ben Davidson

Essay

As home to the first chartered school for girls in the United States, the country’s first medical college for women, one of the earliest chapters of the American Association of University Women (AAUW), and coeducational and women’s colleges, the Philadelphia region provided pioneering models in women’s education. These innovations operated in the context of national upheavals affecting women. Thus, in addition to a unique legacy of significant educational opportunities for elite women and a concern for the futures of working- and middle-class girls, a complex history of gender discrimination and limitations based on race and class also shaped women’s education in the Philadelphia region.

John Poor (1752-1829) established the Young Ladies’ Academy of Philadelphia in 1787, which would become the first chartered female academy in the United States five years later. The school was located on Cherry Street, a mere half-mile from where the Constitution was written. While schools for girls had existed well before the American Revolution, including one within the Philadelphia city limits run by Anthony Benezet (1713-84), the Young Ladies’ Academy represented a new kind of school for a new nation: one officially recognized by a state government. Perhaps best known as the site of Benjamin Rush’s (1746-1814) famous 1787 address on female education, the Young Ladies’ Academy educated young women from throughout the new republic’s eastern states.

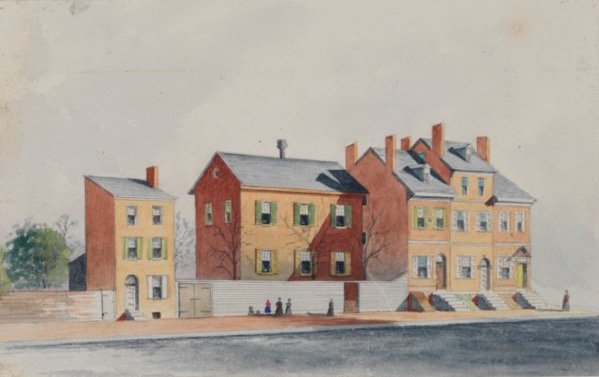

Although the academy was the only school in Philadelphia officially recognized by the state, many other schools educated girls and women in Pennsylvania. For example, the Aimwell School (also housed at one point on Cherry Street, east of Tenth), originally known as the Aimwell School for the Free Instruction of Females, accepted those who were not able to pay the fees of the Young Ladies’ Academy. Founded by the Quaker philanthropist Anne Parrish (1760-1800), it was sponsored and supported by members of the Society of Friends. Parrish’s school was notable not only for its support for impoverished girls, but also for its having been organized and financed by women.

During the Early Republic, women who attended secondary schools generally received education intended as training for domestic life or teaching, a job that was considered temporary until a woman assumed spousal duties. The middle- and upper-class women who were most likely to receive a secondary education generally were expected to marry in early adulthood and thereafter to attend to domestic affairs. Still, women in the Young Ladies’ Academy and elsewhere received a well-rounded education that included subjects such as literature, government, natural philosophy, and science while young men’s education focused on classical subjects, like Latin and Greek, logic and rhetoric.

The Growth of Public Education

Throughout the antebellum period, female seminaries like the Young Ladies’ Academy continued to be the first option for affluent women who wanted a formal education. As textile and other decorative work became acceptable occupations for those who aspired to the middle class, however, vocational schools opened their doors to provide new possibilities for women of more modest means. The most important example of this was the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, founded in 1848 by Sarah Worthington Peter (1800-1877). Thanks to a posthumous bequest from Philadelphia banker Joseph Moore Jr. (1849-1921), it became the Moore Institute of Art, Science, and Industry in 1932 and the degree-granting Moore College of Art thirty-one years later. In the nineteenth century, art and design provided the perfect vocations for aspiring women because they coexisted at the intersection of commerce and leisure. Thus a cycle emerged: vocational schools formed as a result of the growing middle class, and the education they provided helped to grow the middle class. With the market for Victorian consumer goods growing, manufacturers needed both workers who could produce them and consumers who would buy them.

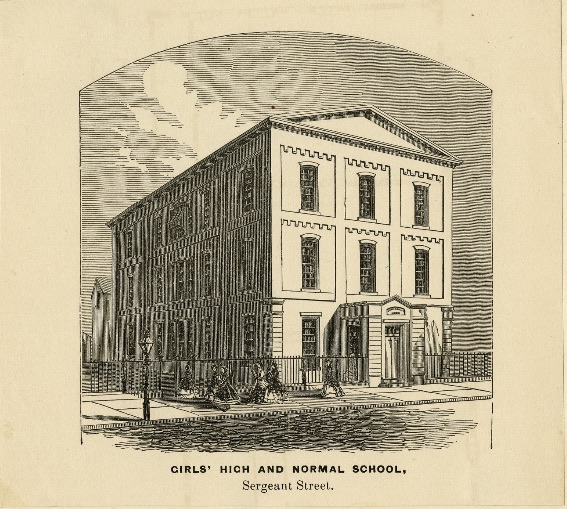

Just as vocational training expanded opportunities for women, so did the Philadelphia Normal School (eventually the Philadelphia High School for Girls), which shifted expectations for women’s participation in education, and in society more generally, by training them to be teachers. In addition to the introduction of art and teacher training, the region witnessed the opening of the first medical college for women in the United States — the Female Medical School of Pennsylvania, eventually renamed the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. The Young Ladies’ Academy had taught chemistry from its early years, and some saw women as particularly suited to scientific pursuits. Still, few women attended medical school in the United States because most men considered them better matched to the often short-lived work of teaching and long-term work inside the home.

While white women may have benefited from the expansion of school opportunities, women of color were usually denied access to a formal education. There were important exceptions, such as Caroline Le Count (1846-1923) who graduated from the Institute for Colored Youth (ICY) in 1863 and soon became the principal of the Ohio Street Colored School in Philadelphia. Like the ICY, the Lombard Street Colored School, founded in 1828, admitted female students. Still, at least some members of Black Philadelphia society thought that the educational system in Philadelphia limited their children. Charlotte Forten (1837-1914) moved to Boston as a young woman in the 1850s because her father, Robert Forten (1813-1864), had decided the education available to her in Philadelphia was not adequate. He had fought the district successfully when it attempted to close the Lombard Street School in 1840, but still decided that his daughter would be better off elsewhere.

Civil War Transformations

During the Civil War era, both Black and white women became increasingly involved in reform movements, such as temperance and abolitionism. They also worked as volunteers in war-related benevolent societies and after the war in schools for freedpeople in the South. Such work prompted the idea that women needed to be educated for lives as reformers as was seen most prominently in the examples of two Quaker schools: Swarthmore College, founded in 1864 as a coeducational institution, and Bryn Mawr College, founded in 1885 specifically for women. The University of Pennsylvania admitted some female students by 1880, including Carrie Burnham Kilgore (1838-1909), who graduated from the law school in 1883, although men and women were not admitted through the same admissions process there until the 1950s. The Delaware Women’s College, founded in 1914 and led by Winifred Robinson (1867-1962), merged with the former Delaware College in 1921 to form the University of Delaware. Temple University (founded as Temple College in 1884) included female students from the beginning, and in 1901 it opened the first coeducational medical college in Pennsylvania.

The expansion in opportunities for higher education led to the founding of private secondary schools for upper-class girls. Feeder private schools for Bryn Mawr College such as Agnes Irwin, Shipley, and Baldwin were established between 1860 and 1900. Women’s organizations in the Catholic Church also opened a number of schools for girls in the Philadelphia region in the post-Civil War era, such as the Academy of Notre Dame de Namur, Mount St. Joseph Academy, and Gwynedd Mercy Academy in Pennsylvania, and Ursuline Academy in Wilmington, Delaware.

Coeducation became the subject of heated debate in the nineteenth century. Boston doctor Edward Clarke (1820-1870) published a widely read treatise in 1873 arguing against coeducation, and Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910) published an edited volume that consisted of prominent women’s replies and counterarguments. Despite such controversy, public elementary schools were usually coeducational by the late nineteenth century due to economic and logistical constraints. In the twentieth century, enrollment of both girls and boys increased at the high school level, and these high schools were generally coeducational. It was mainly elite, private schools that remained single-sex.

Advocacy Organizations

As debates over coeducation played out in the post-Civil War years, arguments about women’s access to higher education continued to intertwine with reform movements such as the crusade for women’s suffrage and the fight for African American rights. In 1886, a group of early graduates from the colleges and universities in the Philadelphia area that admitted women organized the Women’s University Club (WUC). It would affiliate with the American Association of University Women (AAUW) in 1922, becoming an official branch in 1935. Continuing the tradition of activism in women’s education in Philadelphia, WUC members advocated the expansion of public education for girls and women. Along with other women’s organizations including AAUW branches in Delaware (founded in 1923) and southern New Jersey—the Camden County branch was founded in 1929—they worked to expand the role of women in the public sphere.

Many of these efforts coalesced around the issue of voting, and in 1919, as the 19th Amendment was being ratified, suffragists established the League of Women Voters (LWV) to support women in their efforts to become voting citizens. Philadelphia women such as those belonging to the LWV regarded the right to vote as deeply linked with other public causes. Building on informal practices for women that existed outside the educational establishment, the AAUW and the LWV worked assiduously to help women gain access to education and to their rights as citizens.

Expanded roles for women in the public sphere during wartime catalyzed the possibility of new opportunities for them after World War II. Civil rights activists linked the transformation of women’s education to the struggle to end segregation and other forms of racial discrimination. In the 1960s and 1970s, they fought to bring the Brown v. Board of Education decision to bear on Philadelphia-area schools, prompting female college students to call for changes to the education of women by engaging in sit-ins and other protests in support of innovations like the Women’s Studies Program at University of Pennsylvania (1973). Another important project of civil rights activists was the legal process that culminated in Title IX of the Education Amendments Act (1972). It banned gender discrimination in any educational program receiving federal assistance. Because of Title IX, women’s sports at secondary schools, colleges, and universities burgeoned.

Single-Sex Schooling Persists

Even as these changes occurred, however, single-sex education remained in many places. Into the 1980s, women were still excluded from Central High School, one of Philadelphia’s best magnet schools. Following an unsuccessful suit against the School District of Philadelphia that went to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1975, three seventeen-year-old women who were enrolled at the Philadelphia High School for Girls —Elizabeth Newberg, Jessica Bonn, and Pauline King — sued the school district, alleging gender discrimination. Citing the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Common Pleas Court judge William M. Marutani (1923-2004) ruled in 1983 that Central’s admissions policy constituted discrimination on the basis of sex. These young women enrolled at Central High School, but the Philadelphia High School for Girls went on as before.

Indeed, single-sex education continued to thrive in the Philadelphia area at colleges like Bryn Mawr and some private schools as well as the Philadelphia High School for Girls. While legal desegregation and significantly increased enrollment of women in institutions of higher education transformed the educational landscape, early models for female education remained strikingly resilient, as did barriers to opportunity based on race and class. Philadelphia’s history of single-sex institutions and its legacy of reform were shaped by local contexts such as powerful religious and secular reformers and a large middle class. The history of women’s education in Philadelphia demonstrates how regional stories do not always fit neatly into a national frame, as well as how trajectories of reform do not always proceed in a linear fashion.

Ben Davidson is a Ph.D. candidate in United States History at New York University. He is working on a dissertation about the generation of children who grew up during the Civil War era. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

National History Day Resources

- Benjamin Rush, “Thoughts upon Female Education,” from Essays, Literary, Moral, and Philosophical (Internet Archive)

- M. Carey Thomas Letters (Bryn Mawr College Special Collections)

- Edward H. Clarke, Sex in Education (Internet Archive)

- Sex and Education: A Response to Dr. E. H. Clarke's "Sex in Education" (Internet Archive)

- Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (United States Department of Justice)

- Newberg v. Board of Public Education, 1984 (Google Scholar)