Yellow Fever

By Simon Finger | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

For more than a century beginning in the late seventeenth century, sudden outbreaks of yellow fever sowed death and panic throughout Philadelphia and its environs. With medical science seemingly powerless against it, yellow fever was a terrifying and mysterious threat that rivaled any disease of the era in its capacity to take lives and disrupt society.

Yellow fever is a Flavivirus that spreads among humans via the bite of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Once introduced to a human host, the virus begins replicating in the lymph nodes. Initial symptoms include aches and pains, fever, nausea, and dizziness, lasting several days before receding. In serious cases, the symptoms return with renewed intensity as the disease spreads to the liver, inducing jaundice, delirium, and internal hemorrhaging. The victim begins bleeding from the ears and nose, retching up a blend of gastric contents and blood known as the “coffee grounds” or “black vomit.” In the terminal phase, the victim falls comatose as his organs and circulatory system begin to fail, usually expiring as the liver or kidneys finally give out, some 7-10 days after the relapse. Those who survived the ordeal acquired immunity to the disease, but any population composed largely of unseasoned newcomers provided a fertile environment for an outbreak.

Epidemiological evidence suggests that both the virus and its vector originated in Africa. They crossed the Atlantic by the slave trade, becoming endemic in the sugar islands of the West Indies. Once established there, it was only a matter of time before the fever spread to North American ports. From its earliest days, Philadelphia carried on a bustling trade with the Caribbean, and a “Barbados Distemper” struck the city in 1699, felling 220.

For almost a century, yellow fever was an erratic visitor, abruptly appearing after long intervals of relative inactivity. Significant outbreaks appeared in 1741, 1747, and 1762, but major episodes were too uncommon and unpredictable to have a broader political impact until the 1790s, when the fever began striking with greater frequency and fury.

1793: Yellow Fever Returns

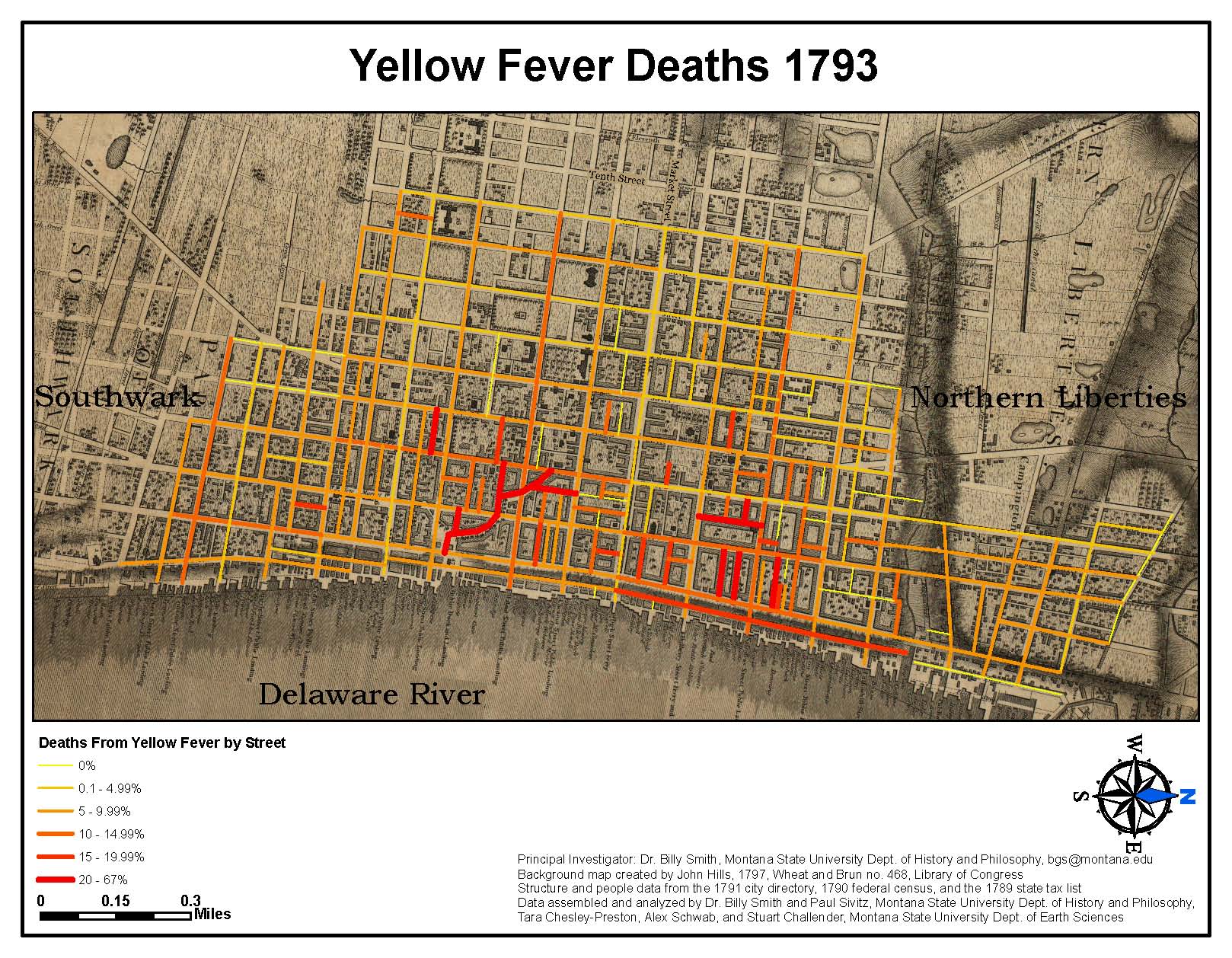

After some three decades absent, yellow fever returned to Philadelphia with a vengeance in 1793, during the period that it served as the capital of both Pennsylvania and the United States. Beginning from a cluster of infections near the Delaware waterfront, the fever spread rapidly through the summer and autumn, fueling panic throughout the city. Those who could fled the city to destinations in healthier countryside, like Germantown and Gray’s Ferry, an exodus numbering in the thousands. Among those who remained, the fever claimed an estimated 5,000 lives. Other American cities embargoed the nation’s capital, fearful that traffic from Philadelphia could introduce the infection.

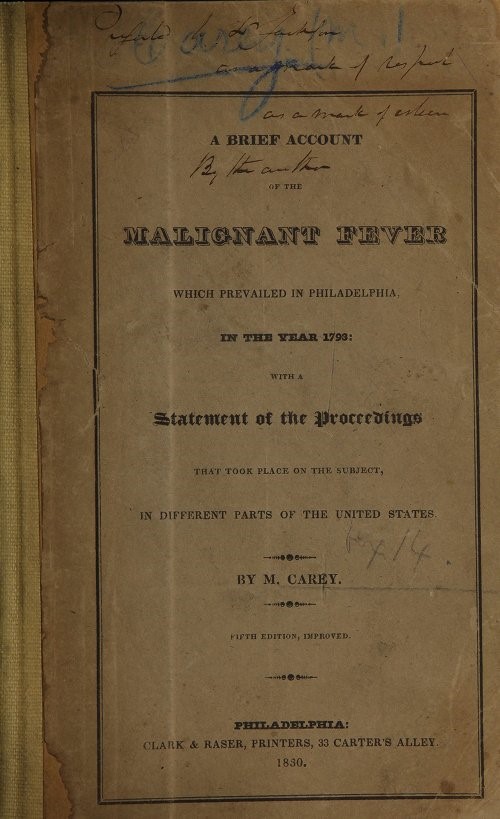

Officers of federal, state and municipal government vacated the city, leaving management of the crisis to Mayor Matthew Clarkson and a committee of volunteers led by merchant Stephen Girard, who organized a fever hospital at the Bush-Hill mansion built by Andrew Hamilton. Black Philadelphians served in disproportionate numbers, owing to a widely held belief that they were immune to the fever, and their heroic service as nurses, porters, and inspectors is widely regarded as a formative event in the history of Black Philadelphia. When printer Mathew Carey published an account of the crisis impugning the conduct of African-American volunteers, Black church leaders Absalom Jones and Richard Allen responded by publishing a powerful rebuttal of the charges, forcing Carey to amend later editions of his tract.

The epidemic also set off a wide-ranging debate over the cause of the fever and the best means of controlling it. Philadelphia’s College of Physicians contended that it was both contagious in nature and foreign in origin, while a faction led by Benjamin Rush, the city’s most celebrated doctor, argued that only domestic environmental factors were to blame. Incorporating insights from both parties, Pennsylvania established a new Philadelphia Board of Health in 1795 to enforce both quarantine and sanitary regulations.

1793: The Model Response

Notwithstanding the new measures, the fever returned seven times in the following twelve years, and 1793 set the model for how Philadelphians responded to subsequent outbreaks. Each episode spurred similar patterns of evacuation, isolation, and scapegoating, and stoked the ongoing controversy within the medical community and motivated broader, though futile, efforts to ameliorate the effects of the disease. Nursing may have offered some comfort, but only winter frost—and its extermination of the mosquitoes—brought an end to each fever year.

The ordeal of fever had a profound effect on the city and the country. It was one of several factors in Philadelphia’s decline relative to rising ports like New York City. It inspired literary and journalistic development as writers and printers discussed, described, and debated the disease. The urban nature of the fever fueled the agrarian romanticism of the Jeffersonian era. And throughout the country, and the broader Atlantic World, medical men struggled to understand a foe that thwarted their best efforts.

Yellow fever struck Philadelphia and other northern ports only sporadically after 1820, but it remained a persistent problem in the American South until the turn of the century, when researchers like Carlos Finlay and Walter Reed unraveled the etiology of the disease and formulated effective measures to control it.

Simon Finger holds a Ph.D. from Princeton University and is the author of The Contagious City: The Politics of Public Health in Early Philadelphia (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2012). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Essay Copyright 2011, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- America's oldest quarantine hospital tied to Philadelphia yellow fever history (WHYY, January 9, 2014)

- Seventh-graders mix history, literature in study of Philadelphia's 1793 yellow fever epidemic (WHYY, March 4, 2015)

- Preservation of the Lazaretto, America's oldest surviving quarantine center, finally gets underway (WHYY, October 31, 2016)

Links

- Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793 (WHYY Audio Tour)

- Yellow Fever Timeline (College of Physicians of Philadelphia)

- Mathew Carey, A short account of the malignant fever, lately prevalent in Philadelphia :with a statement of the proceedings that took place on the subject, in different parts of the United States, to which are added, accounts of the plague in London and Marseilles, and a list of the dead, from August 1, to the middle of December, 1793. (Harvard University Library)

- Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, A narrative of the proceedings of the black people, during the late awful calamity in Philadelphia, in the year 1793 :and a refutation of some censures, thrown upon them in some late publications. Philadelphia : Printed for the authors, by William W. Woodward, at Franklin's Head, no. 41, Chesnut-Street, 1794. (Harvard University Library)