Gloucester County, New Jersey

Essay

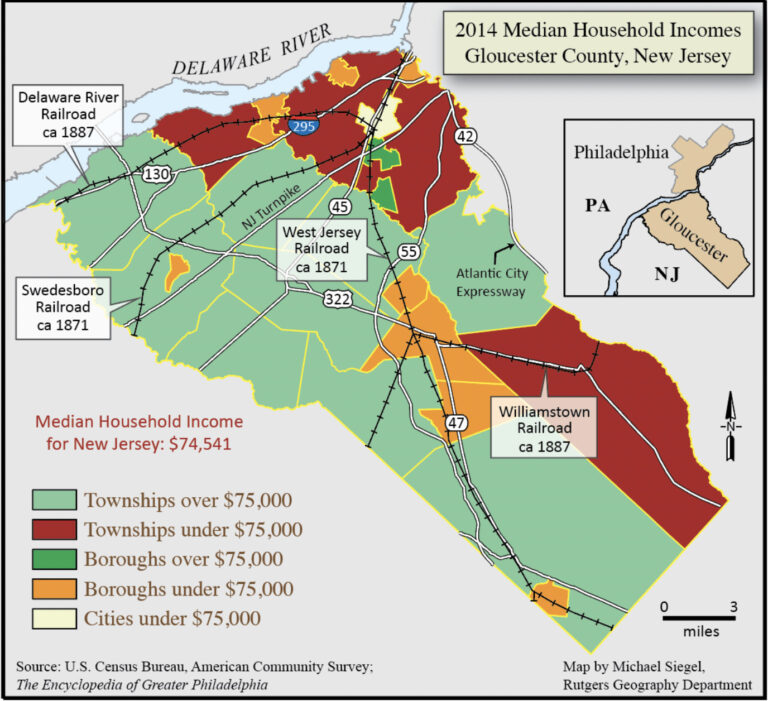

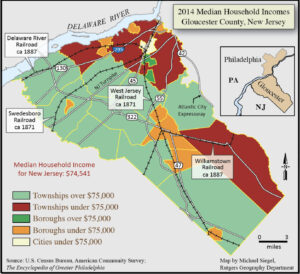

Strategically located along the Delaware River opposite the southern portion of Philadelphia, Gloucester County played an important role in the region, as a location for waves of settlement, industry and recreation, and even defense during the American Revolution. Formed in 1686 with the intention of establishing townships and jurisdictional courts and named for Gloucestershire, England, the county originally stretched from the Delaware to the ocean, encompassing what later became Camden and Atlantic Counties. With a mix of farms, suburban settlement and industry, the county represents a complex mix of historic practices and modern adaptations.

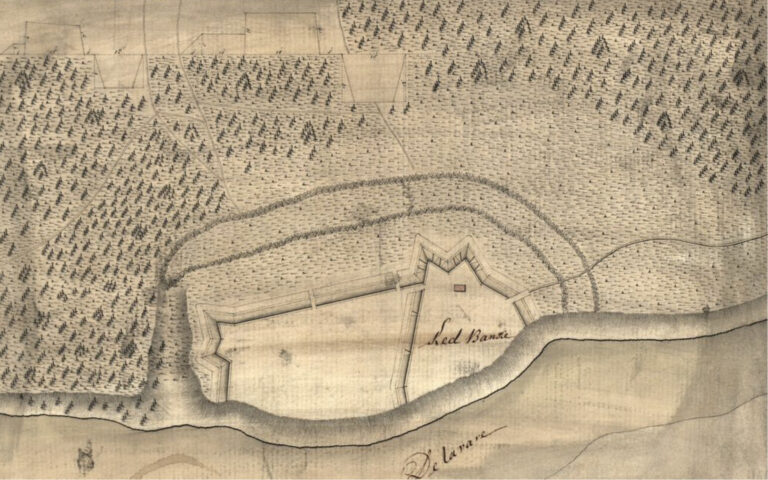

The 337-square-mile territory was first inhabited by the Lenape, who formed villages along the county’s many creeks. Dutch traders arrived in 1623, seeking to trade with the Lenape for furs. Establishing a base at the Big Timber Creek, a tributary entering the Delaware across from Philadelphia, they built Fort Nassau for defense, only to abandon it in 1651 for a location on the other side of the river. The decision was prompted in part by the arrival in 1642 of Swedes, who were themselves anxious both to trade with natives and to establish a new-world outpost, which they christened New Gothenberg. Instructed to treat the Indians fairly and to buy any land that they would sell, settlers purchased land from the Mantua Creek to the Raccoon Creek, further tributaries running from the area’s interior to the Delaware. There they formed the settlement of Raccoon (from the Lenape word “narraticon”). Under a Lease System, unique to New Jersey, the settlement developed south from Raccoon Creek to the present center of Swedesboro, as it came to be known in 1765. It was incorporated in 1903.

In 1664 England, after being stymied by years of internal division, joined the race for settlement in the area when King Charles (1630-85) granted the land between the Connecticut River and the Delaware Bay to his brother, James, Duke of York (1633-1701), who in turn sold it to Sir John Berkeley (1602-78) and Sir George Carteret (c. 1610-80). In 1674, the proprietorship of New Jersey was divided in half, with Berkeley taking West New Jersey, which he promptly sold to John Fenwick (c. 1618-1683) in trust for the wealthy London brewer Edward Byllynge (c. 1623-1687). When the English Quakers Fenwick and Byllynge quarreled over settlement rights, three Quaker trustees, including William Penn (1644-1718), mediated the dispute. Byllynge was awarded the land between Oldman’s Creek and Timber Creek to the river, narrowly avoiding the area’s incorporation into territory subsequently designated as Penn’s Philadelphia. Two hundred and thirty settlers who came with Penn and Byllynge bought land for one penny an acre. The place was named Byllings Port, now Billingsport.

Development Yields Prosperity

With the resolution of his claim, Byllynge became part of a group of prosperous landowning families who dominated the area through their prime locations along the tidal creeks and tributary streams that granted them control over the remaining undeveloped land. Damming streams to make millponds for their sawmills and securing legislation to bank the creeks to nourish their fields, they brought prosperity to themselves and the area. As Philadelphia emerged across the river, they marketed land for sale, stressing its salubrious qualities as a salve to city dwellers.

Settlement increased gradually, with farming dominating most of the occupied land and mills scattered along area creeks. Dating back to the settlement of the first Quaker family in the area in 1683, Woodbury, a part of Deptford Township and located along the creek that gave the village its name, became the county seat in 1786 after fire destroyed the courthouse and jail in Gloucester City, at the mouth of Big Timber Creek, where the county seat had been previously located. A Quaker community from its onset, the village constructed its Friends meetinghouse in 1715.

As revolution captured the country, Quakers in the area struggled. While they opposed taxation by the British Parliament, their pacifism prevented them from taking up arms. Some chose to pay taxes only on that portion unrelated to the war effort, risking fines and even imprisonment, which proved the fate of some who refused to serve. When American troops requisitioned a large part of the 400-acre Red Bank farm of the prominent Whitall family in Woodbury, they inflicted extensive damage to the property where they constructed fortifications—named Fort Mercer—immediately north of the house in an effort to prevent British ships from ascending the Delaware to Philadelphia. Paired with another fortification, Fort Mifflin on Mud Island at Billingsport, the installations utilized chains of large iron-tipped logs known as cheveaux-de-frise spread across the river channels to prevent British warships from coming upriver. American troops successfully repelled a land assault by Hessian troops at the Woodbury Creek in October 1777 and turned back a naval attack the following day. Known as the battle of Red Bank, the fighting focused on the fort at the Whitall farm, which was turned into a military hospital. Success was short-lived, however, as both forts in the county were abandoned by November. Starting in 1895, the Red Bank battlefield area was commercially developed as National Park on the Delaware, a religious resort and retreat for members of the Methodist Episcopal Church, and eventually becoming the borough of National Park.

Given the area’s early Quaker influence, it could not be too surprising that Gloucester County played an active role in the Underground Railroad. In the years before the Civil War several thousand runaway slaves from the upper South traveled through Woodbury north to Mount Laurel or through Greenwich to Swedesboro to Mt. Holly in Burlington County. One of the most important stops on the way was Mount Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church in what was known then as Small Gloucester, now Woolwich Township. Constructed in 1834, the one-story frame building had a secret, three-by-four-foot trapdoor in the floor of the church’s vestibule, affording refuge in the crawlspace under the floor.

Quaker Dominance Slips

Peace brought new challenges to Quaker domination, as national pride advanced military measures anathema to them and aggressive settlement by other denominations reduced their dominance. Further settlement extended along the area’s many creeks, including Big Timber, which powered a number of mills into the 1950s, and Mantua Creek, which enabled transportation, supported saw and grist mills, and encouraged floodplain development for agriculture. Settlement remained limited, however, as evidenced by the modest beginnings of Paulsboro (originally Crown Point), which despite its prime location at the confluence of Mantua Creek with the Delaware, had attracted only a handful of households by the mid-nineteenth century. As new counties formed out of Gloucester—Atlantic in 1837 and Camden in 1844—the county remained thinly settled, with a high of 28,431 residents in 1830, dropping to only 14,655 in 1850 and rising again to 28,649 by 1890.

Early growth was constrained by the limits of overland travel. During the colonial period it took place largely along the Indian trail that ran from Salem to Burlington, a pathway that ultimately became the route of the “Salem Road.” Authorized in 1681 by the “General Free Assembly” held at Burlington, the highway that later became the Kings Road or Highway, was fairly well laid out but not complete by 1688. Where it crossed Big Timber Creek, that crossing spawned a town since few fords of large streams existed at the time. Thomas West built a tavern a few hundred yards away from the creek, which became a favorite stopping place for travelers going to or coming from the lower counties. Originally given the name Buck Tavern, the settlement was renamed Westville in 1840, gaining the reputation in the process as serving as the “Gateway to South Jersey.” As a sign of how limited travel was in the county’s early days, the area’s first turnpike, the Gloucester Turnpike, did not open until 1851.

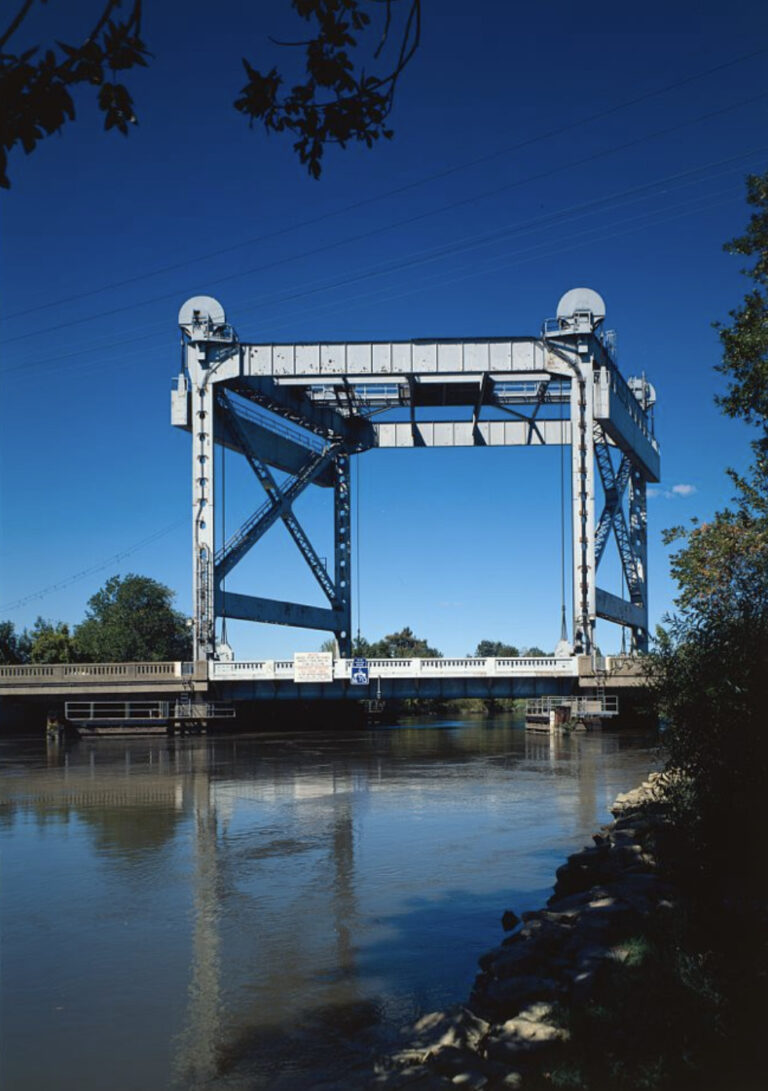

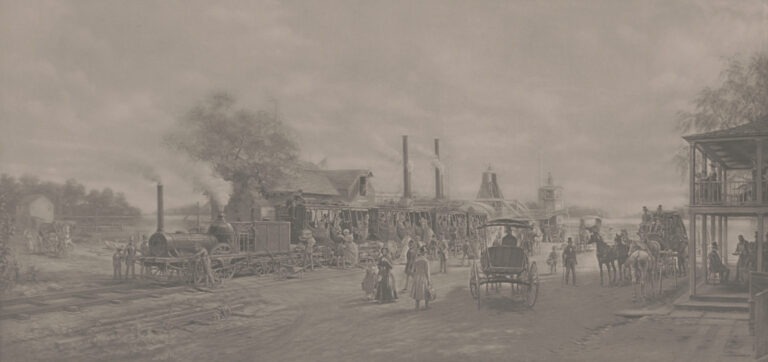

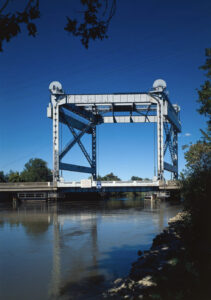

Stagecoaches ultimately gave way to railways, following the advent, in 1838, of the area’s first rail service, offered by the Camden and Amboy Railroad between Camden and Woodbury. Stronger and sturdier bridges made the railroads possible. The line operated three trains each way daily excepting Sundays. Other lines followed, albeit sporadically, and with limited effect. The Millville and Glassboro Railroad incorporated in 1859; the 10.8-mile Swedesboro Railroad extended to Woodbury in 1869; and the Delaware-Shore Line entered Paulsboro in 1876.

It took a pair of regional recreational destinations to spur robust rail traffic to the area. Trolleys from Camden brought picnickers from Philadelphia and points between to the beach in Westville and to Washington Park complete with Ferris wheel and toboggan slide. Although Washington Park succumbed to fire in 1913, never to reopen, area vacationers continued to summer in Westville. Farther south along the Delaware River, at the 28-acre Lincoln Park amusement center, opened in 1890 in Paulsboro, visitors could enjoy concerts and fireworks that were offered every two weeks. Sixteen trains a day brought visitors from the Philadelphia-Camden area. Two ferries and five steamboats made the trip across the river daily. Trains terminated in the historic Quaker settlement of Billingsport located within Greenwich, the county’s first incorporated township. It joined with Crown Point to become the independent borough of Paulsboro 1904. The advent of the automobile forced Lincoln Park’s closure, but Philadelphians continued to use the area as they built their own small resort homes along the shore.

The Emergence of Glass Works

Although agriculture continued to dominate the area, the presence of fine sand encouraged the production of glass as it did in other parts of South Jersey. As early as 1799, Solomon Stranger established the second major glassworks in New Jersey. Known initially only as “Glass Works in the Woods,” the town eventually came to be known, appropriately enough, as Glassboro. Among the survivals of the era is the handsome Victorian Hollybush Whitney Mansion, built in 1849 by Thomas (1813-82) and Samuel (1819-90) Whitney, owners of the Whitney Glass Works. Designed by John Notman (1810-65) and constructed of native Jersey sandstone obtained from the Chestnut Branch quarry, it later became part of the Rowan University campus. It gained international attention when President Lyndon Johnson (1908-73) and Russian Premier Alexei Kosygin (1904-80) met there for their famed summit meetings in June 1967. Nearby, Jacob Fisler (1789-1868), the son of a Swedish immigrant, and his business partner, Benjamin Beckett, began glass manufacturing in 1850 in a central part of the county known as Fislerville. The Fislerville Glass Works spurred the growth of the community to the point in 1858 that the area was incorporated as Clayton. Fisler’s fortunes suffered, however, and two brothers, John M. and David W. Moore, assumed ownership of the plant where workers continued successfully blowing glass until 1911, when the shift to mass-production machinery directed business elsewhere. Despite the loss, William Henry Clevenger, who had come to work for the Moore Brothers in 1890, opened a new facility. Describing himself as a “master glass shearer” or a “window glass blower,” his company passed through several generations until it finally closed in 1964. Taken over once again, and the old forms of reproduction rekindled, the Clevenger plant continued the craft to critical acclaim into the twenty-first century.

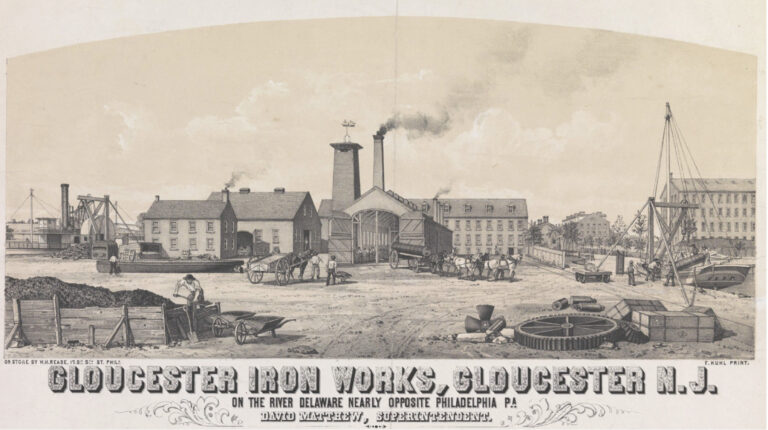

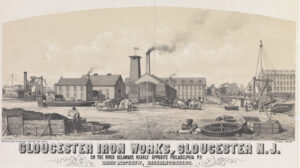

The county’s industrial base diversified in the latter part of the nineteenth century. The DuPont Company opened the Repauno Chemical Works in 1880 in Greenwich, also known as Gibbstown, after Ethan Gibbs, a blacksmith and major landowner, to distinguish the town from Greenwich, Warren County. Repauno was the first of the major chemical and petroleum refiners that would come to dominate the county’s riverfront from West Deptford to Paulsboro. Incorporated in 1880 for the purpose of manufacturing the new high explosive dynamite at a remote site on the Delaware River near Gibbstown and taking its name from nearby Repaupo Creek, the plant was the site of a number of explosions, including one that claimed the life of co-founder Lammot du Pont (1831-84). In 1917 Vacuum Oil opened a refinery to support its export business, also in Gibbstown, though it was popularly known as the Paulsboro plant. Subsequently assumed by Mobil Oil, the site added a research laboratory to its production facility to generate lubricating oil.

Paulsboro itself attracted its share of industry, including an oil storage and fueling terminal that first came into use during World War I. Purchased by Patterson Oil in 1929, the terminal expanded under the new ownership of Eastern Gas & Fuels in 1954, eventually operating under the ownership of British Petroleum until its closure in 1996. Nearby, West Deptford, another town dating back to early settlement, witnessed the transformation of its agricultural roots as industries streamed in. These included Coe and Richman, the largest phosphate works in the country, in 1880, Vacuum Oil in 1917, and Hangsterfer Laboratories, a producer of metalworking lubricants and compounds, in 1935, among others.

Highways Solidify Links to Philadelphia

The introduction of a modern system of state highways in the twentieth century brought Gloucester County further into the orbit of greater Philadelphia’s employment market, spurring suburban growth and development, especially in the towns most easily within reach of the city. In the northeast sector of the county Deptford, which took its name from the English seaport and dated its origins to 1695, remained largely agricultural until the suburban boom that followed World War II. From a population of 7,304 in 1950, the town jumped to 17,878 in 1960 and 24,232 in 1970. With the opening of the Deptford Mall in 1975, it became a regional shopping destination. At Deptford’s southern border, Washington Township, having remained overwhelmingly agricultural since its incorporation in 1836, boomed in the late twentieth century, becoming the county’s most populated jurisdiction with 48,559 people in 2010. Its easy connection to employment centers to the north by Routes 42 (Black Horse Pike) and 168 spurred its growth in the twenty-first century as a premier bedroom community. Directly across the county, the smaller jurisdiction of Woolwich also boomed, growing to 10,200, a 236 percent increase from 2000, in the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Such growth prompted county officials to actively seek the preservation of farmland. Starting in the mid-1990s, the county first issued bonds and, after 2011, drew on state funds to put farmland under covenants to preserve its character. By 2018, the county had preserved more than fifteen thousand acres, the eighth highest total in the state, at a cost of $118.4 million. Targeted especially were the three communities along the Delaware River, Logan, Woolwich, and South Harrison, where development pressures were especially intense.

The importance of the effort was confirmed in the history of Pureland in Logan Township, which formed through the 1970 consolidation of fifty-five farms under the ownership of the State Mutual Life Assurance Company of America and opened for construction in 1975. Praised from its inception as the nation’s first ecologically planned industrial complex, Pureland not just converted farm use, it became the largest industrial complex in New Jersey, hosting 180 companies employing over 8,500 people by 2015, mostly in the arena of warehousing and distribution. Much later, Amazon located its first warehouse in South Jersey in Logan, following shortly thereafter in 2018 with an additional warehouse—this one the equivalent of thirty football fields—in West Deptford. Together the facilities employed about five thousand people.

Overall, Gloucester County was largely white over the course of its history. Although pockets of African American settlement remained from the pre-Civil War settlement associated with the underground railroad—Jerico in Woodbury Heights, for instance—in 2010 county population was still 83.5 percent white, 10 percent Black, and 4.8 percent Latino.

Growth of Pollution

Industry did not come without serious problems of pollution, and in 1979 British Petroleum began a long process of remediation under state supervision at its Paulsboro facility. The company ultimately abandoned the terminal; its demolition began in 1996. Even as remediation continued, public officials debated how best to reuse the site until reaching a decision in 2002 to build the river’s first deep-water general cargo port in fifty years. The 2008 recession delayed the project, but it finally launched in 2014 when shipping company Holt Logistics agreed to give up a sliver of land in Camden to facilitate construction of Holtec International’s new headquarters at the former New York Ship facility in return for the right to operate the new terminal. Shortly afterward, Holt secured a steel company as its first tenant. The terminal processed more than four million tons of imported steel slabs in the first three years after its opening in 2017.

Not all such reclamation projects worked out as well. Mobil Oil’s operation in Paulsboro and East Greenwich also proved devastating to the environment as the disposal of drums containing petroleum products and other hazardous materials polluted soil, surface and ground waters, wetlands, and fish, according to the state. Although Mobil conducted some cleanup efforts, many contaminants remained, prompting a lawsuit against the company. Governor Chris Christie’s (b. 1962) settlement, for $225 million, ended litigation but brought charges that the amount was much lower than it should have been. When Greenwich Township sold the 1,800-acre former DuPont Repauno plant to private investors in 2019, they expected to create a port-related industrial park for imports and exports. Not expected was the new owners’ decision, cleared by the Delaware River Basin Commission, to use the facility to store and export large volumes of liquid fuels produced from fracking Pennsylvania shale gas wells. Under the plan, objected to by state environmentalists, liquefied natural gas would be shipped from a facility in Wyalusing, Pennsylvania, by road or by rail to Gibbstown where it would be loaded directly onto ships for sale overseas or barged to domestic customers.

The reconfiguration of work and living arrangements inevitably set jurisdictions on the path of seeking further revenue sources to keep their tax rates down. As the shopping mall in West Deptford faltered, the township encouraged its renovation. In Paulsboro, city officials hoped to use the opening of its new port facility to attract investment to rehabilitate the two hundred abandoned properties within its jurisdiction. In a particularly distinct set of circumstances, Woolwich sought buyers to redevelop for mixed commercial use and a park a 33-acre Nike missile base that had been closed since 1974, two years after consummation of the SALT I treaty eliminating the nation’s anti-ballistic systems. Change as it might, the county was destined to retain a central position both in South Jersey and in the Greater Philadelphia region.

Howard Gillette is Professor of History Emeritus at Rutgers-Camden and co-editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Information in this essay was current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History