New Castle County, Delaware

Essay

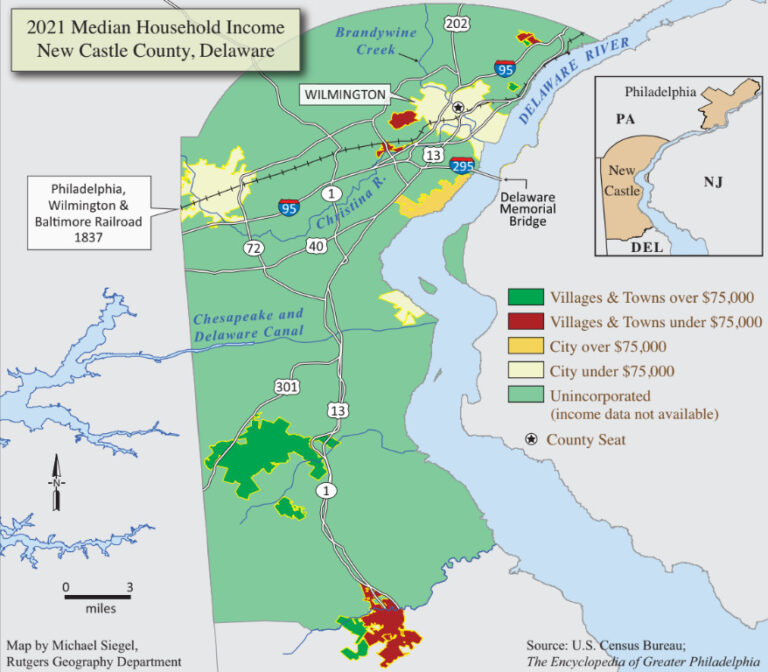

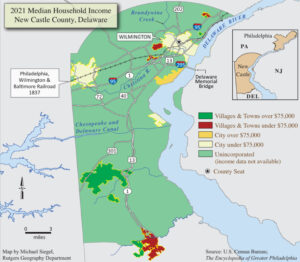

Of the eleven counties in the Philadelphia metropolitan statistical area, New Castle County is perhaps the most varied geographically. Stretching from the Piedmont to the Coastal Plain, it is marked by rolling hills and fast-flowing crystalline streams to the north, sluggish brown tidal creeks meandering towards Delaware Bay to the south. Its northernmost neighborhood at Claymont is virtually an outer suburb of Philadelphia; to the south, the county extends down to the latitude of Baltimore, where Southern culture begins to be detectable. The great majority of the county lies south of the Mason-Dixon Line (drawn between 1763 and 1768). Of all the counties around Philadelphia, it may be the most culturally heterogeneous, for no other touches three states, with distinctive influences flowing in. Southern New Castle County shares the Delmarva Peninsula with Maryland and partly drains into Chesapeake Bay; Wilmington is a stone’s throw across the river from New Jersey; scenic Brandywine Creek knits New Castle County together with Pennsylvania.

Not only is New Castle County diverse, its early settlement history is unusual among the American colonies for the multitude of European nations that claimed it. Sweden, the Netherlands, and England all jockeyed for control throughout the seventeenth century, each establishing settlements that indicated serious claims to the fur trade and other bounties of the New World. Pushed aside were the native peoples who belonged to the Delaware or Lenni Lenape tribe.

Arriving on the ship Kalmar Nyckel, the Swedes built Fort Christina near the later site of Wilmington in 1638. The fort comprised the first Swedish settlement in the Western Hemisphere. Dutch director-general Peter Stuyvesant (ca. 1592-1672) established Fort Casimir, later called New Castle, just south on the Delaware River in 1651.

The British Take Over

Fort Casimir, later New Amstel, in 1651, became the most important Dutch town in America outside of the New York region. A British takeover came in 1664, with New Amstel renamed New Castle after the populous riverfront port in northeast England. By 1682 Quakers were starting to flood the region, quickly diluting whatever remained of the culture of New Sweden. Upon arrival in America—at the wharf in New Castle in 1682—William Penn (1644-1718) moved quickly to give representative government to the Three Lower Counties, including New Castle County, which had officially been founded in 1673, with its courthouse at New Castle. Otherwise, he feared that these counties could be wrested from his control by Lord Baltimore (1605-1675), who dreamed of annexing them to Maryland. The matter was hotly contested: Lawsuits raged in London until 1750, finally determining that the Delaware counties belonged to Pennsylvania. Not that the marriage was always amicable. Anglican Delawareans often clashed with their pacifist Quaker neighbors to the north, finding them dilatory in appropriating funds for military necessities, in particular the protection of Delaware Bay against enemy ships and pirates.

The early history of New Castle County was inextricable from that of Philadelphia. It was one of Pennsylvania’s “Three Lower Counties,” providing crucial access to the sea. The town of New Castle thrived as an overnight stop for travelers coming and going from Philadelphia, and to the south of there, Port Penn attempted to compete with Philadelphia’s shipping trade.

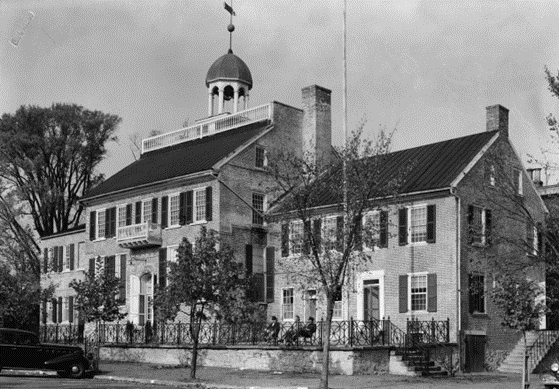

Philadelphia’s influence on Wilmington (chartered in 1739) was extensive. Along streets that bore the familiar Philadelphia names (Walnut, Spruce, and Pine) rose sturdy brick Georgian houses as fireproof as those recommended by William Penn in the Quaker City, and the handsome Old Town Hall (1798) virtually copied Philadelphia’s Congress Hall. Even Wilmington’s Old Swedes Church was built in 1698-99 by a Philadelphia mason of English descent in an English architectural style. The sophisticated colonial houses of Odessa in southern New Castle County showed how closely the leading families there were tied to Philadelphia by the grain trade around 1770.

War Comes, 1777

The Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolution brought war to the quiet agricultural landscapes of New Castle County. George Washington’s September 1777 efforts to protect Philadelphia from British attack centered on Delaware before shifting just north to the banks of the Brandywine at Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, where the second largest land battle of the Revolutionary War was fought, the Battle of the Brandywine. The opening skirmish of that campaign happened in New Castle County, the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge, on a site preserved in the twentieth century by the State of Delaware and, according to much-debated legend, the place where the Stars and Stripes may have first flown in battle. Later Washington’s army marched rapidly to Chadds Ford along the river, through what later became First State National Historical Park (founded 2013), Delaware’s first and only federal park.

New Castle County’s early history was thoroughly shaped by rivers and boats, the only practicable means of getting products to market, and a galaxy of little towns sprang up along waterways, only to dwindle and fade once the railroad passed them by. The town of New Castle is perhaps the best example, filled with stylish houses of the Federal period, clustered near the once-thriving riverfront. Several blocks from the wharfs stands the Court House (begun ca. 1730), one of the nation’s oldest surviving government facilities, scene of heated trials regarding slavery and abolitionism—a reminder that slavery was legal in more Southern-leaning New Castle County for eighty years after Pennsylvania first took steps in 1780 to abolish it. The Court House was also, according to legend, the point from which Delaware’s distinctive Circular Border with Pennsylvania was measured in colonial times (1701 and again in 1750, actually from multiple center points). But New Castle’s economy sputtered once railroads eclipsed water transportation. The gradual nineteenth-century decline of the town was measured by the fact that the county seat eventually shifted to flourishing Wilmington in 1881, leaving New Castle as a time capsule of early American architecture.

At New Castle, the full impact of successive changes in transportation is evident. The historic road that linked to Wilmington crossed the top of an ancient dike, one of several built by the Dutch and English starting in the 1650s to improve transport and reclaim marshland for agriculture. Remarkably, these still protect the low-lying town from flooding, and some were rehabilitated as barriers against sea-level rise as recently as 2014. Later, travelers both famous and obscure got off boats to and from Philadelphia, then trudged up narrow Packet Alley in New Castle to catch overland transport to the Chesapeake Bay. In 1832, New Castle briefly became the terminus for one of America’s first railroads, the New Castle & Frenchtown, and the nation’s second-oldest train station still stands there, though exhibiting a typically modest Delawarean scale, hardly bigger than a broom closet.

Canals, Railroads, Highways

The 1820s brought a nationwide canal mania. A canal through New Castle County linking the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays had been proposed as early as the seventeenth century. As Philadelphia and Baltimore grew, a fourteen-mile canal emerged as a favored way of reducing the four-hundred-mile trip between them to less than one hundred. Partly funded by the federal government and constructed between 1824 and 1829, the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal extended along the middle of the Delmarva Peninsula. The Deep Cut at Summit Bridge (east of Chesapeake City, Maryland) excavated by 2,500 men with shovels, was one of the most arduous engineering feats of the age. The C & D Canal cost nearly nine times more per mile than the slightly earlier Erie Canal as the route through soft Coastal Plain sediments was constantly plagued by mudslides.

The ambitiously titled Delaware City was established at the east end of the canal in anticipation of a boom. It was backed by two brothers, originally from New Jersey, who hoped it would steal much of Philadelphia’s shipping. The canal did see steady increases in tonnage through 1872 and played a critical role in Union troop movements during the Civil War. Thereafter, competition from railroads was stiff, and Delaware City largely fizzled. Much enlarged in the twentieth century, the C & D Canal grew to one of the busiest waterways in the nation, carrying forty percent of the maritime freight of the Port of Baltimore and much of Philadelphia’s as well. Culturally, it formed an unofficial divide between North and South, “Below the Canal” being a Delaware byword for a more rural and relaxed lifestyle in the so-called “Slower Lower” part of the state—a distinction that blurred with rapid suburbanization.

The advent of the railroad completely refigured the patterns of travel and commerce in New Castle County. Wilmington mushroomed due to its location on the main line between New York and Washington, D.C. The routing of the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore (1837) through northern New Castle County triggered an explosion of industry, including tanneries, carriage factories, and textile and flour mills. Starting in the 1830s, Lobdell Car Wheel Company mastered the difficult art of forging metal wheels tough enough to withstand high-speed railroad use. Nearby, Jackson & Sharp dominated American production of railroad coaches after the Civil War. Another historic railroad line cut through the county (and the outer suburbs of Wilmington) in the 1880s, the Baltimore & Ohio, with picturesque stations on the northwestern edge of Wilmington and at Newark designed by renowned Philadelphia architect Frank Furness (1839-1912), both subsequently demolished in the automobile age.

New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad

But the most historic railroad story in New Castle County was the first-ever attempt to cross the Delmarva Peninsula by rail: the New Castle & Frenchtown Railroad. It came extremely early, with surveying begun in spring 1830, the year the Baltimore & Ohio opened for business in Maryland as America’s very first railroad. A private company undertook the project, with Philadelphia investors playing a key role and Philadelphia architect and engineer William Strickland (1788-1854) working as a consultant. The reach of this enterprise was remarkable. Trains ran on granite blocks hauled from Maryland and Pennsylvania, on which were stretched timbers from Georgia, topped with iron straps from Liverpool, England, nailed in with spikes forged at Troy Nail Works in New York. Notably, two locomotives were imported from England in 1832, duplicates of the lightest locomotives in use on the famous Liverpool & Manchester Railroad (opened 1830), designed by the esteemed Robert Stephenson (1803-1859). Locomotives were named Delaware and Maryland; Pennsylvania was ordered a year later, in 1832.

Another hundred years later New Castle County again saw a transportation innovation of importance, not just nationally but internationally. Delaware’s fertile farms lay tantalizingly close to the giant urban market of Philadelphia, but poor roads meant that highway transport was slow, causing fruits and vegetables to perish. Industrialist T. Coleman du Pont (1863-1930) proposed a concrete highway to stretch the entire length of the state, hoping for a multilane thoroughfare with swift cars separated from slower trolleys, trucks, and horses, a suggestion only partially acted upon. He personally funded the DuPont Highway, later U.S. Routes 13 and 113, which was completed in 1923 and served as a key proving ground for highway-improvement campaigners nationwide. The smooth, white concrete invited high speeds, but problems were soon identified. Curves were frighteningly tight, headlight glare dazzled drivers, and head-on collisions were frequent. An experiment followed in 1929-1933, when the forty-five miles from Wilmington to Dover were reconfigured as a divided highway, Delaware Dual Road, said to be the first in the world to adopt the dual roadway technique (well before the German autobahns opened in 1935-36, or the Merritt Parkway, Connecticut, in 1938-40, or the Pennsylvania Turnpike in 1940). Closely involved with the DuPont Highway was Coleman’s son, Francis V. du Pont (1894-1962), later a leading figure in the creation of the U.S. interstate highway system under President Dwight Eisenhower (1890-1969).

Heritage of the du Ponts

For most of its history, New Castle County was heavily agricultural, in common with the entire state. As late as the 1920s, Delaware was first in the country for its percentage of land under cultivation. But at the same time, New Castle County’s Brandywine Creek had been a key center of the industrial revolution in the United States, with scores of mills springing up. Here about 1790 occurred the historic American debut of the mechanized production of flour and, in 1817, machine-made paper for newsprint and books, helping spur the nineteenth-century explosion in publishing. Well before that, in 1794, Scottish immigrant William Young (1755-1829) had opened the Delaware Paper Mill at Rockland, providing paper for his shop and printing press on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, so that Brandywine paper from New Castle County became the watermarked standard for U. S. government documents.

In 1802 the du Ponts arrived as part of the larger wave of refugees from the French Revolution to found their famous gunpower-manufacturing complex along Brandywine Creek and subsequently dominate the state economy. By the early twentieth century, the DuPont company was the nation’s top producer of gunpower and dynamite and increasingly dominating the chemical industry as well, with products woven into the daily life of every American, from toothpaste to nylon hosiery to automotive paints. Later still came Tyvek for building insulation, Kevlar for bulletproof vests, Teflon for nonstick pans. The wealth of the family became legendary. The corporation brought high salaries and an influx of talent, making Wilmington the wealthiest city per capita in the United States following World War I. The family was ardently philanthropic, founding schools and churches for the company’s early Irish and Italian workforce. Pierre S. du Pont (1870-1954), great-grandson of E. I. du Pont (1771-1834) who immigrated from France, proved one of the most generous contributors to charity in the nation’s history. Concerned about the poor quality of schools throughout Delaware, he began to finance them himself, including the sumptuous P. S. duPont Middle School in Wilmington (1935), one of the most beautiful public schools in the country, a brick-and-limestone masterpiece in Delaware’s signature Colonial Revival style. He also paid for eighty-nine mostly rural schools for African Americans (built 1919-28), one of which, School House #112C, remains preserved as Iron Hill Museum near Newark after it was shuttered, like virtually all of the Black schools, following the court-ordered desegregation of all Delaware schools in 1965.

Another legacy of the du Pont family was the preservation of scenic land in Piedmont New Castle County and the creation of house-museums that enjoy a national reputation as “Chateau Country,” a major driver of tourism to the region. Countless workers were employed on these estates, from housekeepers to chauffeurs and gardeners, many of them recent immigrants from Europe. When not engaged in his legendary feud with certain du Pont cousins, Alfred I. du Pont (1864-1935)—proud of his direct line of descent via “oldest sons” from the family in France—built a state-of-the-art children’s hospital on the grounds of his French-style estate, later called Nemours Mansion & Gardens. Hagley Museum & Library preserves the first du Pont home in America, Eleutherian Mills, and the nearby gunpowder manufactory. Winterthur was the dream of Henry Francis du Pont (1880-1969), another cousin of A. I.’s. Starting in 1927, he built a gigantic addition to showcase his growing collections of classic American interiors and antiques. The existing thirty-two-room mansion was supplemented by a wing with more than a hundred “period rooms” housing the largest collection of American antiques in the world.

Farm Fields and Crossroads Towns

Long overwhelmingly rural outside of Wilmington, New Castle County developed slowly, with farmers cultivating grain that was ground at mills along local streams, then shipped by the Delaware River to distant markets. At crossroads that sometimes dated back to Indian times, settlements sprang up with taverns to serve travelers who were just passing through Delaware on their way to somewhere more populous. Often these were millers transporting grain. At the hamlet of Christiana, near Christiana Mall, the crossroads settlement pattern remains intact. The main north-south colonial highway ran directly through town, as did an important east-west county road, so that a Connecticut visitor of 1749 was surprised to find, after countless Mid-Atlantic log houses, “a Clump of very fine brick houses a Dozen or more & Several Taverns,” this being “a place . . . of much Business.” A wharf on the Christiana River provided a small but prosperous port for this well-inland settlement. George Washington (1732-1799) slept regularly in Christiana taverns during his frequent travels between Virginia and the North.

Milling flourished on many of New Castle County’s streams, as at the John England Mill east of Newark, founded by an immigrant from Staffordshire in the 1720s, two decades before he built the sturdy brick colonial house that survives amidst modern suburban development. This miller was English, but many of his neighbors were Scots-Irish, the most populous minority in the county, and not far west were a group of Welsh settlers at Iron Hill. Newark itself was, in the eighteenth century, yet another crossroads town, although strung along a considerable straightaway, later named Main Street. Just outside of town, the Curtis Paper Company operated on White Clay Creek from 1789 until 1997, the longest-running paper mill in America. Home to the University of Delaware, Newark was a sleepy place for generations, but after World War II, with the expansion of the school and construction of two DuPont facilities and a Chrysler plant, it grew to be Delaware’s third-largest town (population 31,000), nearly as large as Dover.

Unusual in Delaware for having been founded away from any navigable river, Middletown in southern New Castle County coalesced at another early crossroads. The place experienced rapid growth after the railroad came through in 1855. Peach farming on the fertile “Levels” brought prosperity, and sizable Victorian houses went up on Cass and Broad Streets. Demographically, the lower county was Southern, with slaves working in the peach orchards. Freedom was not far away in Pennsylvania, however, making Middletown a vital link in the Underground Railroad that extended straight through New Castle County, up to the dreaded Market Street Bridge over the Brandywine in Wilmington—a covered span watched closely for runaways. In a celebrated 1845 case, a Quaker farmer and abolitionist of Middletown, John Hunn (1818-1894), assisted a group of escaped slaves who arrived in the night from Maryland’s Eastern Shore, part of a regular flow from the South seeking freedom. Neighbors called the local constable, who arrested the runaways and delivered them to the jail in New Castle.

Ethnic Diversification, Rise of Suburbia

The familiar agricultural ethos of New Castle County persisted for centuries until finally succumbing to implacable economic forces in the mid-twentieth-century. A 1992 memoir by elderly Emma Mariane (1903-2005) about farm life in Brandywine Hundred, north of Wilmington, recounts the swift disappearance of a rural way of life, long organized around haymaking, cutting corn with knives, bottling milk. She tells how small-scale dairies, once thriving, were finally regulated out of existence by modernizing state health authorities. With the coming of supermarkets after 1945, the King Street farmers market downtown—where curbs were lined with hundreds of horse wagons bearing eggs, broiler chickens, and an array of vegetables—was ruled unsanitary and closed, meaning locals had nowhere to sell their products. With big business ascendant, self-sufficient farms failed. Mariane’s little farm converted into a nursery serving the front-yard needs of suburban homeowners; all the neighboring ones were paved over for housing developments.

Along with the rest of the Philadelphia region, New Castle County was utterly transformed by suburbanization and the automobile after World War II. Growth in industry, stimulated in part by the war effort, reshaped the county. Companies relocated to the area to take advantage of cheap land and proximity to major markets, the area lying in the burgeoning megalopolis about midway between New York and Washington. Wilmington had long been ringed by trolley suburbs, but now the automobile allowed neighborhoods to spring up in odd corners largely untethered from the city—for example, seven hundred boxy housing units sprouting in a cow pasture at Fairfax in 1950, by developer Alfred J. Vilone (1905-98).

Like many of his customers, Vilone was of Italian descent. New Castle County long had relatively little ethnic diversity, other than African Americans and the many Irish who had built antebellum canals and railroads and later worked in cotton mills. But a huge influx starting in the 1880s changed the picture dramatically. German immigrants became bakers, butchers, and cabinetmakers; Poles excelled in leather-tanning and ironworking. After 1900 they were joined by Italians whose many enterprises included boot- and shoemaking, tailoring, and masonry. Compared to other ethnic groups, Italians grouped tightly together rather than dispersing, with concentrations at Wilmington’s Little Italy around landmark St. Anthony’s Church (1926) as well as at Hockessin and Claymont. By midcentury their descendants had mastered the English language and spread throughout the county, producing a dominant cultural strain marked by intermarriage between Irish and Italians. The postwar suburbanization of northern New Castle County owed much to these ethnic groups abandoning Wilmington rowhouses, joined by many others who sought to escape crowded city conditions in South Philadelphia.

For generations, practically everybody had gone to Market and King Streets in downtown Wilmington to go shopping—old photographs show the sidewalks thronged at Christmastime. The focus shifted dramatically after World War II when the Philadelphia firm of John Wanamaker (1838-1922) proposed to build a state-of-the-art department store on sixteen acres along the edge of a forest far outside of town (1948-50). Seemingly audacious, this marked the beginning of a whole new era of land use in the county, as the company broke free from Wilmington taxes and zoning and felled trees to build an enormous parking lot of the kind one never found in crowded downtown. The elegant marble architecture in “conservative-modern” style by local architect Alfred V. du Pont (1900-70), son of A. I. who owned Nemours, was meant to suggest a country club, with an Ivy Tea Room overlooking the Brandywine River, an aspirational design for upscale Wilmingtonians moving to the suburbs. The idea was to lure out-of-state shoppers as well, a model later taken up by the Christiana Mall, which opened east of Newark (Delaware 1 at Interstate 95) in 1978. Its name, borrowed from the nearby village, recalled Queen Christina of Sweden (1626-1689) and Delaware’s earliest permanent European settlement. It became one of the most successful regional malls in the country, with an appraised value of a billion dollars. New Castle County’s convenient location, low property taxes, and lack of sales tax kept Christiana Mall thriving, although the Brandywine Wanamaker’s succumbed by the end of the twentieth century to a plethora of new malls and retail outlets in the booming region.

Delaware Memorial Bridge

The Wanamaker store had been planned to coincide with the opening of the Delaware Memorial Bridge (1948-51), which finally linked northern Delaware to the New Jersey Turnpike and allowed an influx of commerce, fully linking New Castle County to the surging economy of the larger megalopolis. A plan for the bridge was conceived in earnest during the last months of World War II, as a war memorial, with Francis V. du Pont a key proponent. This suspension bridge represented an extraordinary engineering achievement, its 2,150-foot span over the busy shipping lanes of the Delaware River claiming for a time the title of sixth-longest bridge ever built.

New highways and automobiles shook old-fashioned Wilmington to the core. The city had long dominated New Castle County and as recently as 1920, . But during the 1950s, Wilmington’s stature swiftly collapsed as riverfront industries shut down and the population of its suburbs nearly doubled, and it ignominiously fell out of the list of American cities of 100,000 for the first time in fifty years. By 1960, only 31 percent of county residents lived in Wilmington, the suburban population of the county having . Although urban depopulation was a national trend, the DuPont company remained, and as a result the Wilmington urban area in 1955 was the sixth wealthiest in the U.S. in terms of average family income ($6,900). By 1960, DuPont . Money was available for a vast rebuilding of downtown, revolving around a key question broached as early as a Wilmington Chamber of Commerce publication in 1926: “‘Where shall we park the car?’ Wanamaker’s had shown that suburbanites would skip downtown altogether, so long as parking was easy outside of town. As an answer, in the 1960s twenty-two vast blocks downtown were leveled for urban renewal—mostly replaced by parking lots, along with a few governmental buildings, as commercial development seldom materialized. Increasingly, drivers found little to lure them into Wilmington, then palpably in decline, with stores closing and aging Victorian neighborhoods looking decrepit.

As with Philadelphia, Interstate 95 had a powerful and ultimately deleterious effect on urban planning in Wilmington. New Castle County had long been a place that one traveled through to get somewhere else, going back to the Kings Highway of colonial times. Now the greatest of America’s north-south interstate highways would run directly through the county, traversing twenty-three miles. It could have bypassed Wilmington through wealthy suburbs to the west, but this was overruled in favor of annihilation of several blocks through the residential sections adjoining downtown, starting in 1959.

The Impact of Interstate 95

The damage that I-95 did to Wilmington has been emphasized to the point, perhaps, of overstatement; the centuries-old city might have declined in any case. The highway did contribute to economic growth outside of the town, allowing a rapid commute to Newark in the 1960s and then, in the 1980s, to sprawling new developments in Pike Creek and Hockessin. Thanks in part to that often-maligned interstate, New Castle County has thrived in recent decades. Delaware , incorporating more than a million businesses (including two-thirds of the Fortune 500), with thousands of local jobs the result, from bankruptcy lawyers to corporate-service specialists. Powerful New Castle County politicians have long nurtured relationships with corporations. A disproportionate number of governors, congressmen, and senators have lived in this one corner of a small state, including a charismatic senator who became president of the United States, Joseph R. Biden (b. 1942). Like many residents of New Castle County, Biden was born someplace farther north—in Scranton, Pennsylvania, a fading town that his father soon fled, seeking economic opportunity as a used-car salesman in Delaware and buying a house in a new development near Claymont. The 1981 Financial Center Development Act built on Delaware’s business-friendly reputation by giving special breaks to the credit card industry. An influx of highly educated outsiders came to the area from New Jersey and elsewhere, tipping the political scales firmly towards the Democratic party in a state long considered Southern-leaning and conservative. Many banks are headquartered in New Castle County, and residents are engaged in financial careers at nearly twice the national average. Service-sector jobs have supplanted manufacturing: recently demolished were the post-World War II Chrysler automotive plant at Newark and the General Motors plant at Newport, replaced, respectively, by a high-tech “innovation community” associated with the University of Delaware (2010) and a colossal Amazon fulfillment center (2019)—both symbolic of the constantly changing economic and demographic picture in an ever-evolving New Castle County.

W. Barksdale Maynard is the author of eight books on American history, art, and architecture, including Buildings of Delaware in the Buildings of the United States series (University of Virginia Press, 2008), The Brandywine: An Intimate Portrait (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014), and Artists of Wyeth Country: Howard Pyle, N. C. Wyeth, and Andrew Wyeth (Temple University Press, 2021). He lives in Greenville, Delaware. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2023, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- Battle of Brandywine (Brandywine Battlefield)

- Historical Context for the DuPont Highway (Delaware Department of Transportation)

- The Gilpins and Their Endless Papermaking Machine (The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography)

- The History of Rockland Mills at Brandywine Creek State Park (Delaware State Park Adventures Blog)

- History of the Winterthur Estate (Winterthur Portfolio)

- Evidences of American Home Life: Henry Francis du Pont and the Winterthur Period Rooms (Winterthur Portfolio)

- New Castle County, Delaware QuickFacts (United States Census Bureau)

- The Tiny State Whose Laws Affect Workers Everywhere (The Atlantic)

- National Historic Landmark Nomination for the Middletown Historic District (National Park Service)