Salem County, New Jersey

Essay

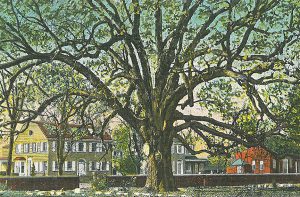

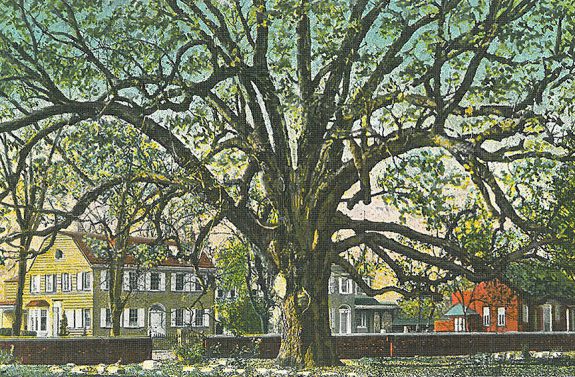

Before Philadelphia’s founding, Salem, New Jersey, was the first English Quaker colony along the Delaware River. Established in 1675, the city of Salem had early prominence and served as a port of entry, but was soon overshadowed by Philadelphia. Although eighteenth-century settlement in Salem County consisted primarily of farmers and craftsmen, the proximity of the Philadelphia market by ship, steamboat, and railroad spurred additional industry during the nineteenth century, particularly glass manufacturing, canneries, dairies, poultry, fishing, and truck farming. With the advent of World War I, DuPont Powder Works and Chambers Works permanently changed Salem County, bringing an influx of new residents and immigrants and establishing the precedence of industry over agriculture. The Delaware Memorial Bridge and the modern highway system increased the number of commuters living in the county while working in Delaware, Philadelphia, and other South Jersey counties. By the twenty-first century, Salem County remained a rural region of farm fields and small towns, still close to the urban hub of Philadelphia. However, the decline of former manufactories created a pressing need to increase jobs, industry, and tourism.

The area that became Salem County was first settled by the Lenape, followed by Swedes who arrived in the Delaware Valley in 1638 and purchased the New Jersey side of the Delaware River from Cape May to Raccoon Creek. To curb English settlement and establish their precedence over the Dutch, the Swedes built Fort Elfsborg at what was later called Elsinboro to guard the Delaware River. By 1655, when the Dutch took control, the Swedes had settled at Finns Point and other locations on the neck of land between the Delaware and the Salem River.

The first permanent English settlement in Salem County was established by John Fenwick (1618-83), who arrived with Quakers and other Englishmen on the Griffin in 1675. Prior to his departure, Fenwick had purchased the West Jersey holdings of Lord John Berkeley (1602-78)—a transaction of disputed validity. After negotiations with William Penn (1644-1718) and others, Fenwick was granted one-tenth proprietorship of West Jersey. Shortly after Fenwick arrived to plant his colony, he affirmed his claim by purchasing from the resident Lenape three tracts of land stretching along the Delaware River from Oldman’s Creek to the Maurice River, known as the Salem Tenth. At the mouth of the Salem River, Fenwick founded the city of Salem, which became a port of entry in 1682. Although the Swedes still lived in the land along the Delaware River, Fenwick brought them under English rule, and they were eventually absorbed by the English colony. Due to ongoing controversy regarding his ownership of the land, Fenwick had to relinquish all but 150,000 acres of his colony to William Penn in March 1682, just months before Fenwick died. The Salem Tenth officially organized as Salem County in 1695 with Salem City as the county seat; it was one of the two original West Jersey counties and included the region that later separated to form Cumberland County.

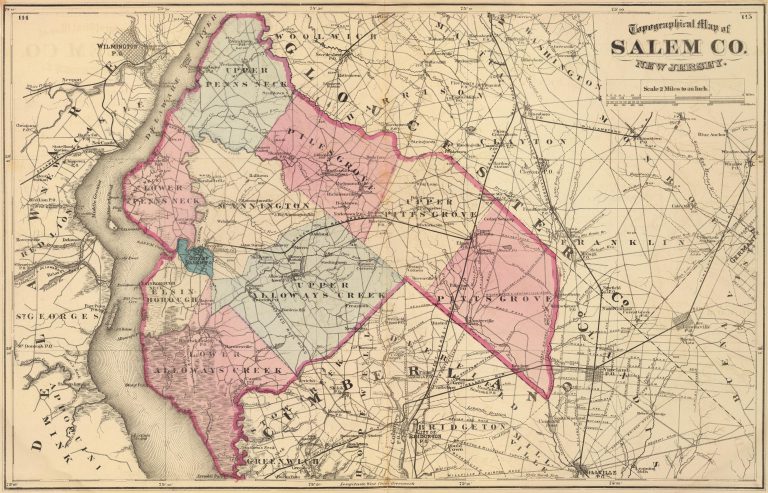

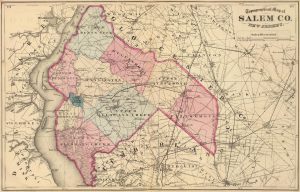

The first major road laid out in Salem County was the Kings Highway, commissioned by the West Jersey Assembly in 1681 to connect Salem with Burlington, at that time the other principal town of West Jersey. The next major roads, beginning in 1707, connected Salem with Greenwich in the area that later became Cumberland County. Settlements formed around three principal bridges across Alloways Creek: Hancock’s Bridge, Quinton’s Bridge, and Thompson’s Bridge (later Alloway). By the early 1700s, settlements had also formed inland at mills in Woodstown and Daretown along the Salem River and at Centerton along Muddy Run, feeding into the Maurice River. At the northern border of the Salem County, Pedricktown and Sculltown (later Auburn) formed along Oldman’s Creek. After Cumberland County separated from Salem County in 1748, Stow Creek became the southern border of Salem County. Roads continued to be laid out to connect these early settlements, which generally centered on mills or taverns.

During the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, additional English colonists arrived from Great Britain and New England and French Huguenots and Dutch migrated south from New York. The county’s strong Quaker presence and religious tolerance attracted Quakers and Baptists. Less nobly, wealthy Salem County residents purchased enslaved persons from the West Indies and Africa for housework and farm labor. By 1737, Salem County’s population had reached 5,884, with 184 slaves forming roughly 3 percent of the population. Initially residing in log houses, many colonists built pattern-brick houses during the early eighteenth century; a few dozen examples of this unique architectural style survived as private residences or tourist attractions into the twenty-first century.

Farms and Manufactories

From the port of Salem, the early settlers exported grains (wheat, corn, rye, and oats), animal products (beef, pork, tallow, and pelts), and timber (cedar posts, shingles, staves, and cordwood) to New York, Boston, and the West Indies. As Philadelphia emerged as a rival in foreign trade, Salem shifted focus to supplying the Philadelphia market. In addition to mills, farming, tanning, woodworking, and masonry, the first major industry was glass making, which Caspar Wistar (1696-1752) of Philadelphia established in 1738 with a glass works at Wistarburg in Alloway Township. The Wistarburg Glass Works, which operated until the Revolutionary War, attracted many German immigrants to Salem County.

The Revolutionary War figures strongly in Salem County lore, although no major battles occurred in the county. Salem County provided militiamen for the Continental Army, provided cattle and fodder for Washington’s troops at Valley Forge, and fiercely fought the British and Loyalists during skirmishes. With rich farm fields, Salem County tempted both the American and British troops, whose foraging in Salem in 1778 prompted the Battle of Quinton’s Bridge and the Hancock’s Bridge Massacre.

By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the rich soil of Salem County had been exhausted of nutrients, farms yielded poor harvests, and many farmers migrated to the Midwest. In 1826, however, the discovery of marl, an excellent fertilizer, in Pilesgrove led to revitalized soil and solidified agricultural presence in Salem County. Farmers raised cattle, potatoes, fruits, vegetables, poultry, and dairy products to supply the Philadelphia markets, and fishing for shad, herring, and sturgeon became important industries along the Delaware River. As the need for shipping increased, shipbuilders in Salem and Alloway responded by producing schooners, canal boats, brigs, and later steamboats. By the 1830s, steamboats ran regularly from Salem and Penns Grove to Philadelphia and Wilmington, transporting crops to market and goods for export.

Salem County’s population rose by 1800 to 11,371, including 85 slaves and 607 free Blacks. The oldest African Methodist Episcopal Church in New Jersey, established in Salem City in 1800, predated the founding conference of the A.M.E. denomination in Philadelphia in 1816. The Quaker influence significantly reduced slavery in Salem County, and by 1830 only one slave remained, with approximately 1,400 free Blacks among the total population of 14,155 residents. The significant increase of free Blacks (by 1830 making up 10 percent of the population) resulted partially from the Underground Railroad and an influx of escaped slaves. Because of its proximity to Philadelphia and its strong Quaker presence, Salem County became a haven for many fugitives, who settled in free Black communities in Mannington, Pilesgrove, and other townships.

When the Civil War began, Salem men quickly enlisted in the Union Army. Local women also contributed to the cause, most notably Cornelia Hancock (1840-1927), who served as a nurse after the Battle of Gettysburg. Although no battles occurred on Salem County soil, Fort Delaware in the Delaware River housed Confederate prisoners in overcrowded and unhealthy conditions; 2,436 prisoners died and were buried in Salem County at Finns Point Cemetery, across the river from Fort Delaware.

Impacts of the Railroad

In 1863, the West Jersey Railroad connected Salem to Camden and Philadelphia, passing through Salem County’s small towns along the way. The Delaware River Railroad crossed the northern region of Salem County to Penns Grove in about 1876. These railroads offered daily passenger trains between Salem County and Philadelphia, allowing residents to commute to work in the city. In addition, the railroads offered a new way to transport goods and produce to the metropolitan area. Taking advantage of the shipping opportunities, industry in Salem County expanded. Glass factories formed in Salem and Quinton in 1863; the Quinton Glassworks supplied glass for the Centennial Exhibition buildings in Philadelphia in 1876. A variety of other factories (spindles, shoes, cigars, and others) also emerged near these railroad lines. The American Oil Cloth Company started in Salem in 1868. Later, Mannington Mills became a significant flooring manufacturer.

The railroad also allowed farmers to ship tomatoes, potatoes, asparagus, and other vegetables and fruit to Philadelphia to be sold or to South Jersey canneries such as Campbell Soup in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Small local canneries emerged in several Salem County communities, and a Heinz food processing plant operated in Salem City from 1905 to 1977. The increased need for agricultural workers attracted immigrants from Europe (especially Italy), and some canneries built housing for immigrant workers. In addition to produce, caviar harvested from sturgeon became a key export from Penns Grove during the 1880s. Dairy farms shipped milk to Philadelphia, and local creameries created ice cream and other dairy products for export. Abbott’s Alderney Dairies, founded in Mannington, shipped milk by train to the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876; the creamery moved to Philadelphia the following year. By the 1920s, roads and trucks had surpassed railroads as the preferred shipping method, allowing farmers to drive produce to Camden and Philadelphia.

In addition to facilitating commerce, railroads and steamboats brought tourists, vacationers, and immigrants to Salem County. The New Jersey Southern Railroad brought Russian Jewish immigrants from New York City to Pittsgrove Township, where in 1882 they established the Alliance Colony, subdividing the land into fifteen-acre parcels with the intent of forming an agricultural utopia. With limited agricultural experience, however, the settlers had to supplement their crops with clothing factories and other industry, later adding the poultry and egg businesses. The community expanded during the early 1900s, but by 1959 the Jewish presence had waned, and a new wave of migrants–primarily African Americans and Hispanics–moved into the houses.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, vacationers from New York, Philadelphia, and other cities rode the railroad to parks at lakes such as Rainbow Lake, Centerton Lake, Palatine Lake, and Parvin State Park, while steamboats traveling daily from Philadelphia to Salem brought vacationers to groves along the Delaware River such as French’s Grove at Penns Grove and Silver Grove in Pennsville (later known as Riverview Beach Park). These parks and groves featured swimming, boating, rides, and pavilions for skating and dancing. The Wilson Line provided regular transportation from Philadelphia, Camden, and Wilmington to Penns Grove and Salem along the Delaware River, which became popular vacation spots for city residents.

As automobiles took over from railroads, the ferries crossing between Delaware and Salem County could not adequately handle the surge of vehicles, and the Delaware State Highway Department constructed the Delaware Memorial Bridge between Wilmington and Deepwater (the first span opened in 1951, and the second in 1968). Along with the bridges in Gloucester and Camden Counties, highways linked Salem County to Philadelphia, Delaware, and the rest of the country. Commuters traversed the county on the New Jersey Turnpike (completed 1951) and I-295, vacationers headed through the county to the shore, and trucks exported and delivered goods.

Population Growth and Change

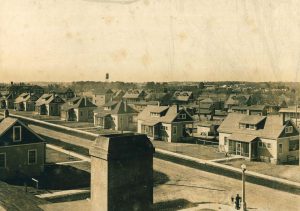

Industry boomed at the DuPont Powder Works once World War I broke out, and Salem County changed forever. DuPont opened the Powder Works at Carneys Point just south of Penns Grove in 1893 to create smokeless gunpowder for the Spanish-American War, but World War I dramatically increased the need for munitions. Workers from around the United States, as well as immigrants from Italy, Russia, Poland, Ireland, Germany, and other countries, flooded into Carneys Point, Penns Grove, and Pennsville to work at DuPont. Between 1910 and 1920, Salem County’s population increased by about ten thousand, compared to a typical increase of one thousand in prior decades. Carneys Point’s population jumped from 744 to 6,259, while neighboring Penns Grove’s population increased from 2,118 to 6,060. During World War I, the plant employed a high of over twenty thousand people. To accommodate the influx of workers, DuPont built temporary housing, barracks, and bungalows, and even put up tents to house the workers. With dramatic increases of students, Penns Grove and Carneys Point expanded and built new schools.

In 1917, DuPont started the Dye Works (renamed Chambers Works in 1945) at Deepwater in Pennsville Township, initially focusing on creating dyes, an industry previously dominated by war-torn Germany. The Chambers Works became a worldwide leader in organic chemicals by discovering and creating materials such as Teflon, nylon, and Freon. DuPont remained a major employer for the rest of the century, with high wages that continued to draw both locals and new residents to Salem County. By 1964, approximately 25 percent of county households included a DuPont employee. Although Carneys Point’s population dropped after World War I, the population increased again from 1930 to 1960, remaining around seven thousand or eight thousand for the rest of the century. From 1930 to 1970, Pennsville dramatically increased in population, rising from 2,933 to 13,296, making it the most populous municipality of the county. A once-rural area had become densely populated, lining the industrial belt along the Delaware River between Salem City and Penns Grove.

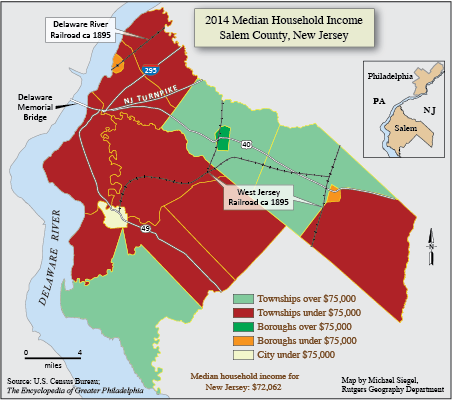

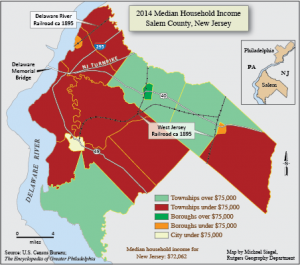

In the latter half of the twentieth century, Salem County’s industrial towns slumped, especially Salem City and the Borough of Penns Grove. Both places experienced decreases in jobs and industry as factories and small businesses closed, prompting a rise in poverty and abandoned housing. Because Salem and Penns Grove also had high minority populations, racial tensions aggravated the situation. At the time schools integrated in 1947, most Salem County elementary schools were segregated while high schools were integrated. It took several years before all the schools integrated, due to reluctance as well as the need for additional facilities to accommodate extra students. An NBC television special in 1964, which calculated that Salem City most embodied “Average Town USA,” also revealed local prejudice. Racial tensions continued to escalate during the following decade with a few cross burnings that were soon halted. At the time, African Americans comprised 29 percent of Salem City’s population.

By 2010, minorities had become the majority in Salem and Penns Grove; Salem City was 62 percent African American, and Penns Grove was 40 percent African American and 28 percent Hispanic. These regions, along with Carneys Point and Pennsville, also had the highest numbers of foreign-born residents and Hispanics. Puerto Rican migrant workers began arriving after World War II to pick vegetables between spring and fall, and later settled permanently. The Puerto Rican Action Committee (PRAC) of Southern Jersey, formed in 1971 by Salem County Agricultural Workers to rally the Hispanic community and advance opportunities, remained active into the twenty-first century.

Blighted by poverty, over 20 percent of the households in Salem City and Penns Grove received public assistance in 2010, and the unemployment rate was 27 percent in Penns Grove and 18 percent in Salem. Over 60 percent of houses in these cities were rentals, with high percentages of multiple unit dwellings and several hundred vacant homes, 22 percent vacant in Salem City in 2010. Volunteers from organizations such as Stand Up For Salem (established in 1988) attempted to revitalize the county seat through restoring neglected buildings, developing downtown businesses, fund-raising, and promoting events with moderate results.

Small Town Survival in the Suburban Era

In contrast to the declining urban populations, Salem County’s rural regions gained residents as suburban housing and commuting became popular in the second half of the twentieth century. Rural townships experienced growth in the 1950s or gradually increased throughout the century. Pittsgrove Township received the most new residents, increasing from 2,808 in 1950 to 8,121 in 1990. Developments such as Palatine Lake Village and trailer parks attracted new residents, many of whom longed to live in a rural setting. The completion of Route 55 in 1989 and the ease of access to I-295 and the New Jersey Turnpike made living in rural Salem County, while commuting to jobs outside the county, feasible. According to the 2010 census, although 14,002 Salem County residents worked within the county, 10,730 residents commuted to work in other South Jersey counties or out of state, with the top work locations being Cumberland County (30 percent), Delaware (24 percent), Pennsylvania (16 percent), and Camden County (11 percent).

PSE&G’s Salem Generating Station, built between 1968 and 1981, became Salem county’s largest employer. Consisting of three nuclear power plants on Artificial Island off the coast of Lower Alloways Creek, the facility supplied New Jersey, Philadelphia, and the Delmarva Peninsula. DuPont Chambers Works, Mannington Mills, and hospitals in Mannington and Elmer continued to be significant employers. Although Salem’s glass factory closed in 2014, Salem Community College (founded in 1972) continued the glass tradition by offering Glass Art and the only Scientific Glass Technology degree in the country. The Salem County government attempted to expand use of the railroad between Salem and Swedesboro, repairing it to connect with the port of Salem, another underused asset in the twenty-first century. New businesses in Salem County included distribution centers and warehouses at the Gateway Business Park in Oldmans Township. Still, the need for more jobs and businesses to counteract high property taxes remained.

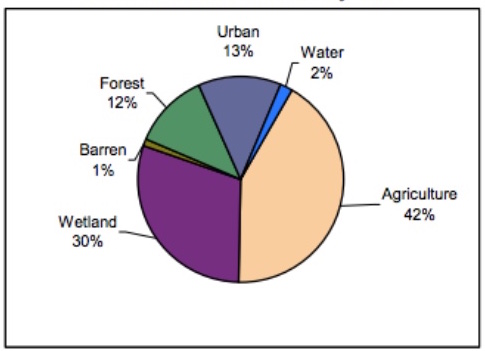

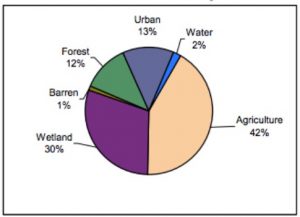

Despite its industrial presence, Salem County remained primarily agricultural with small towns, and many residents resisted further development. In response to the community’s desire to preserve farmland, the county freeholders established the Salem County Agriculture Development Board and the Agricultural Land Preservation Program (1990) and the Farmland Preservation Plan (2006). At both the county and municipal levels, voters approved taxes dedicated to support Farmland Preservation, resulting in over three hundred farms preserved after 1990. By May 2017, Salem County had the most preserved farmland in the state, with 35,726 acres under protection. Salem County farms still produced corn, hay, soybeans, vegetables, and fruits for market; horse farms, nurseries, sod farms, and wineries also were on the rise. The biggest tourist attraction in Salem County remained the Cowtown Rodeo, founded in 1929, which is the longest running weekly rodeo in the United States. Other cultural attractions bringing tourists from urban areas included the Salem County Fair, the Appel Farm Arts & Music Center, the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Pow Wow, the Arts in Bloom tour, historic house tours, wine trails, and other festivals, as well as a multitude of outdoor activities at local state parks and nature preserves. Whether marketing rural charm, exporting goods and produce, or seeking employment at a commutable distance, Salem County continued to benefit from both the opportunities and the needs of Philadelphia and its suburban area.

Bonny Beth Elwell is a Salem County historian and genealogist, serving on the board of several historical organizations. She works as the editor of the Elmer Times newspaper, the Library Director of the Camden County Historical Society, and is the author of Upper Pittsgrove, Elmer, and Pittsgrove (2013) and other publications. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Salem County, New Jersey

- Southern NJ Reports: Salem County (Senator Walter Rand Institute for Public Affairs, Rutgers-Camden)

- Salem County News (NJ.com)

- David Brinkley’s Journal, “Election Year in Averagetown,” Salem New Jersey, 1964 (YouTube).

- Salem County Economic Development Council

- Salem County Data Book (Salem County Planning Board, 2013)

- Salem County and the American Revolution

- Salem County Farm First to Install Conservation Project Under New Program to Help Farmers Protect Water Quality (New Jersey Department of Agriculture)

- 100th Salem Farm Preserved, June 2003 (Salem County Agriculture Development Board)

- Farm Markets in Salem County