Broad Street

Essay

“No other street in America quite compares with Broad Street,” wrote E. Digby Baltzell, author of Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia, of the varied architecture north and south of City Hall. Philadelphia’s Broad Street goes past stores, churches, synagogues, museums, funeral parlors, fast food places, gas stations, apartment houses, and rows and rows of row houses. After driving the entire length of the street, Washington-based poet Stanley Plumly once said, “What I love is the immediate juxtaposition of neighborhoods. I don’t think there’s a street that represents America more totally in the full spectrum and range of humanity than Broad Street in Philadelphia.”

Broad Street is, as its name implies, the city’s broadest north-south street. At one hundred feet in width, the north-south arterial is indeed wide, but its length is more remarkable. From the extreme limits of South Philadelphia, it shoots north into Center City and beyond to North Philadelphia, right to the edge of Montgomery County. It is the longest straight urban boulevard in the United States and the longest straight street in Philadelphia (although traffic must circle City Hall in the middle). An old Philly aphorism is: “They say Broad Street is the straightest street, but when you get to City Hall, it gets real crooked.” Also, an old local joke is to send someone to Fourteenth Street. There is no Fourteenth Street, as Broad Street is where that street would be.

Broad Street is the north-south counterpart to Market (formerly High) Street. When surveyor Thomas Holme (1624-95) prepared the first plan of the city of Philadelphia for William Penn (1644-1718), only Broad and High Streets were named. Twelfth Street was designated as Broad Street, and this rough road bisected the town almost exactly at its middle in what was then wilderness. The plan also designated a public square in the vicinity of this intersection, supposedly the center of the city, because Holme believed it to be the watershed dividing the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. The plot was therefore called Center Square. Penn intended that the Public Buildings (City Hall) of Philadelphia would one day go there.

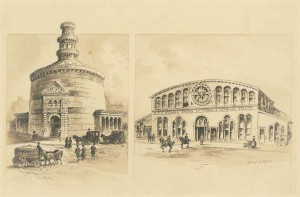

Broad Street was moved to Fourteenth Street by the 1730s, as that was closer to the actual midpoint between the two rivers. Surveyors also corrected Holme’s error regarding Center Square and placed the commons where it is today—the location of City Hall. Troops drilled in and around Center Square during the War of Independence, and the French army under Rochambeau camped there on the way to Yorktown. Later, Center Square became the site for Philadelphia’s first waterworks.

Broad Grows North and South

After the Revolution, Broad Street grew, first to the north: The road was extended from Vine Street to Ridge Road (Avenue) in 1811. It continued north through the nineteenth century, and its northernmost extensions were created between 1903 and 1923. The street was also lengthened to the south: In 1819, the road reached from South (formerly Cedar) Street to Dickinson Street. With the city-county consolidation of 1854, a rudimentary version of Broad Street extended as far south as the later site of the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

Broad Street began to fill in by the first third of the nineteenth century. As the city’s population grew westward from its original concentration near the Delaware River, South Broad Street became distinguished by elite residences, hotels, and cultural institutions. Wealthy Philadelphians who wished to escape the crowded conditions of old Philadelphia built fine mansions along South Broad. Several expensive hotels also opened on South Broad by the 1850s, including the LaPierre House at Broad and Sansom, which was touted as the most luxurious hotel in America. These hotels also housed clubrooms and rathskellars for the many social organizations based along both South and North Broad well into the twentieth century.

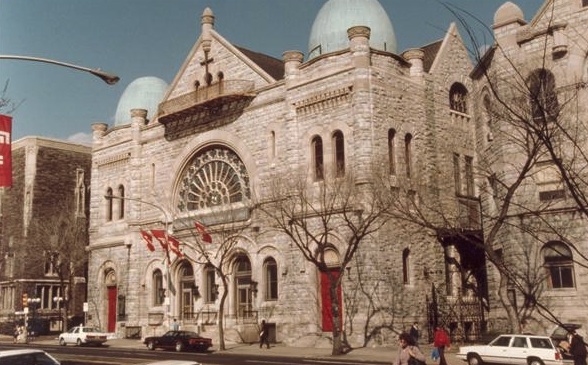

Closest to Center Square, Broad Street also became home to cultural institutions. On South Broad, the Academy of Music opened at Broad and Locust Streets in 1857, and it was joined by the Union League eight years later. To the north, during the second half of the nineteenth century Broad Street from City Hall to Race Street became lined with businesses and institutions including the Masonic Temple, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Offenbach’s Garden (replaced in 1892 by an Odd Fellows Temple), and the Adelphi Theater (demolished in 1881). Farther north, the street had an industrial character, created by Matthias Baldwin (1795-1866), who founded his great locomotive factory in the 1830s at the corner of Broad and Spring Garden (outside the city limits at that time). This industrial site grew to encompass several blocks between Callowhill and Spring Garden Streets as other manufactures joined the Baldwin Works in this gritty manufacturing area along North Broad Street.

After the Civil War, North Broad Street became one of Philadelphia’s leading elite addresses. Many mansions were built in the Gothic and Victorian styles, mostly to house the families of wealthy industrialists and middle managers, such as those who owned and worked at Baldwin Locomotive Works and associated factories. Other fabulous homes were erected for the owners and operators of traction companies who laid down trolley tracks in most of the streets of Philadelphia (and other cities too). These men—William L. Elkins (1832-1903) and Peter A. Widener (1834-1915)—and their enormous Victorian homes represented the peak of North Broad’s development.

Sidewalks Grow, Too

Reflecting the evolution of the street, Broad Street’s sidewalks were broadened and large granite blocks were used to pave the roadway in the 1870s. In 1894, Broad was the first street in Philadelphia surfaced with asphalt—the latest in paving technology at the time—for primitive automobiles. This work, instigated by Mayor Edwin S. Stuart (1853–1937), cost the city half a million dollars. The blocks of stone (Belgian blocks) that had previously lined Broad Street were used to replace the cobbles in nearby small streets. And, like Market Street, Broad Street subsequently became the route of a subway line, initially opened in 1928 with additions made in 1936, 1956, and 1970.

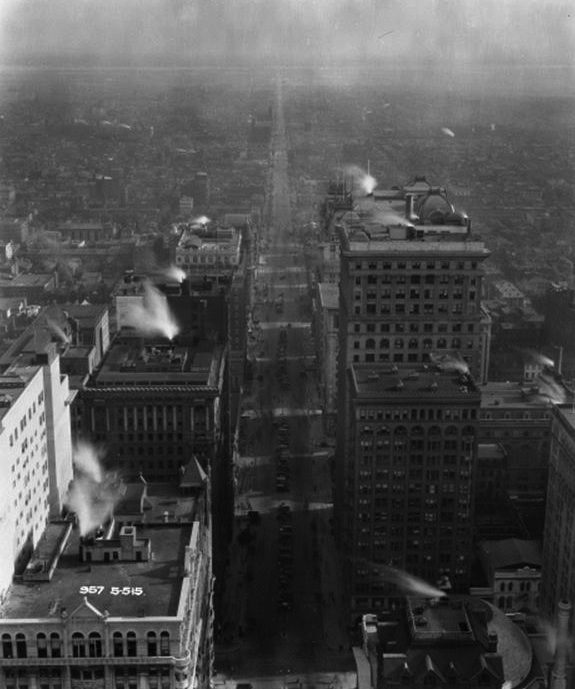

By far the biggest change for Broad Street occurred in the last decades of the nineteenth century, when City Hall was constructed on Center Square, encompassing the entire block and interrupting travel on both Broad and Market Streets. The completion of the “Public Buildings” encouraged the development of office and financial headquarters along the thoroughfare close to the new seat of government, and under the watchful eye of the statue of William Penn high atop the building’s tower. Philadelphia’s City Hall was designed to be huge in every way so as to make a statement about the city’s wealth and industrial might.

With the relocation of city government to Broad and Market, residential and office skyscrapers replaced many of the mansions and hotels along South Broad (although several fine hotels, such as the Bellevue Stratford, remained). The Pennsylvania Railroad’s Broad Street Station, opened in 1881 directly across from City Hall, added to the mix and helped transform Broad Street from a quiet institutional and residential roadway into a bustling commercial thoroughfare.

Broad Street also experienced a major building boom farther south in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Much of this was due to the Vare Brothers—William Scott (1867-1934), George (1859-1908) and Edwin (1862-1922). They were construction contractors and politicians who ran a corrupt South Philadelphia political machine and reaped most of their construction and waste-handling business through municipal contracts. Besides building projects throughout South Philadelphia, the Vare brothers were responsible for the modern grading of Broad Street south of Oregon Avenue.

Cultural Magnet

North and south, Broad Street remained a cultural magnet into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Philadelphia’s famous New Year’s Day Mummer’s Parade has strutted and strummed along two miles of South Broad for over a hundred years. In the late 1990s, the crux of theaters, galleries, and performance spaces on Broad Street between City Hall and Washington Avenue was designated the “Avenue of the Arts.” Similar plans have been envisioned for North Broad Street as well.

In addition to such longstanding musical landmarks as the Academy of Music, Broad Street around the area of South Street became known in the early twentieth century as a center for jazz and gospel music. These developments were an outgrowth of the Great Migration, the northward movement of African Americans that occurred during and after the First World War. When labor demand created by World War II precipitated another African American migration to Philadelphia, North Broad Street also became an important cultural center for Black Philadelphians with such venues as the Uptown Theater, which opened in the 1920s as a movie theater but became a destination for soul and rhythm and blues performers from the 1950s to the 1970s.

North Broad Street played a role in the nation’s transportation history as a link in the Lincoln Highway, and it became Philadelphia’s Automobile Row with showrooms for the latest models. However, by the mid-twentieth century, North Broad experienced a severe decline. The well-heeled property owners of North Broad Street moved to suburban estates north and west of Philadelphia by the 1940s. Many of their mansions were subdivided into apartment buildings, while others were demolished and replaced by retail establishments, automobile dealerships, and gas stations.

Redevelopment initiatives included those of civil rights leader Leon Sullivan (1922-2001). A Baptist minister, he moved to Philadelphia in 1950 and became the pastor of Zion Baptist Church, 3600 N. Broad Street. In 1964, Sullivan formed the Opportunities Industrialization Center along North Broad to provide job training for African Americans. He also established the Zion Investment Association, which invested in new businesses in Philadelphia. As a result, the first Black-owned and developed shopping center in the world, Progress Plaza, was built in 1968 on North Broad. Other grassroots organizations, such as North Philadelphia Block Development Corporation (founded in 1976), lobbied for increased community development funding for the downtrodden neighborhoods flanking North Broad Street.

Broad Street grew from a rural lane in the countryside into a dense urban boulevard, as well as perhaps the most important street in Philadelphia. The central axis of nineteenth century industrial tycoons became a main artery for Philadelphians of all backgrounds, extending from Center City north and south through the entire city and its diverse neighborhoods.

Harry Kyriakodis is the author of Philadelphia’s Lost Waterfront (The History Press, 2011) and Northern Liberties: The Story of a Philadelphia River Ward (The History Press, 2012). He is a founding/certified member of the Association of Philadelphia Tour Guides. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- North Broad Street renaissance underway, Philly leaders say (WHYY, May 14, 2014)

- Photos: Then and now, Philadelphia's North Broad Street (Keystone Crossroads Project via WHYY, July 10, 2014)

- Philly police headquarters moving to former Inquirer building on North Broad (WHYY, May 24, 2017)

- Boyz II Men boulevard is more than a street name for Philadelphia natives (WHYY, June 25, 2017)

- Restored to former glory, The Met opens on North Broad Street (WHYY, December 3, 2018)

Links

- Avenue of the Arts Tour (@philart.net)

- An Expressive Gateway at Broad and Fairmount (PhillyHistory.org)

- The Widener Mansion (PhillyHistory.org)

- Freedom Theater (ExplorePAHistory)

- Broad Street Station (Philadelphia Architects and Buildings)

- Old Broad Street Station (ExplorePAHistory)

- Baldwin Locomotive Works (Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network)