Immigration (1930-Present)

By Daniel Amsterdam and Domenic Vitiello | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

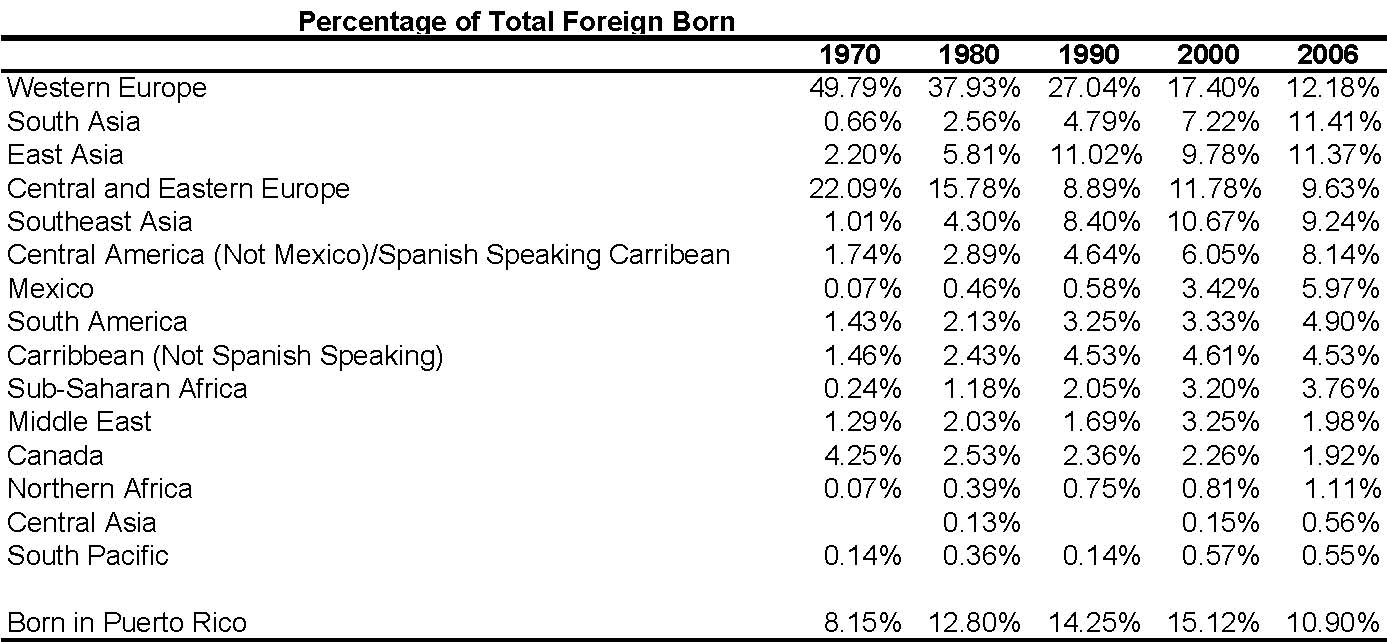

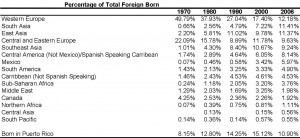

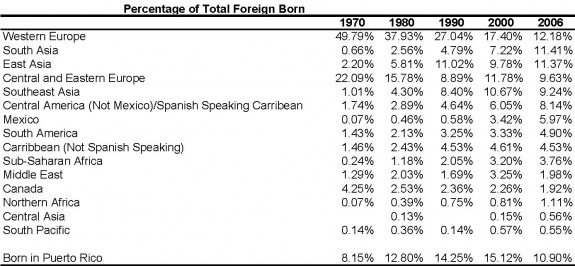

For most of the decades since the United States’ immigration restriction acts of the 1920s, Philadelphia was not a major destination for immigrants, but at the end of the twentieth century the region re-emerged as a significant gateway. Beginning with changes in U.S. law in 1965 and accelerating by the 1990s, immigration added large, diverse groups of newcomers to the city and suburbs. Immigrants and refugees dramatically altered the region’s economic, social, and political life and its geography of race and ethnicity. While the city and region remained more Black and white than the global cities of New York, Los Angeles, or Miami, newcomers from Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Eastern Europe significantly diversified the population of Greater Philadelphia.

During and after World War II, with limited foreign migration, internal migrations transformed the city and region. From the 1940s through the ’80s, two major demographic trends – the Second Great Migration of African Americans and mass suburbanization of the region’s white population – were joined by a third smaller, but significant development, the Great Migration of Puerto Ricans. Between 1940 and 1980, the nine-county region’s Black population grew from 330,000 to more than one million. The Puerto Rican population expanded from 3,000 in 1950 to almost 55,000 in 1980, and by 2010 to more than 120,000, the second-largest Puerto Rican population in the country, behind only New York. As U.S. citizens, Puerto Ricans are not an immigrant group, but as migrants to the mainland they became the largest group of newcomers to Philadelphia since the 1920s whose first language was not English.

Puerto Ricans and African Americans settled mainly in the old rowhouse neighborhoods in Philadelphia and working class suburbs like Norristown, places earlier immigrants and their children left in the post-World War II era. Unlike earlier generations, however, the new migrants entered a region whose manufacturing economy crashed in the 1950s through the ’80s, as the jobs that had sustained these communities disappeared. Socially, economically, and spatially, in this period the region became a different destination for new immigrants. Although the federal government re-opened the borders with new immigration regulations in 1965, immigrant settlement in Philadelphia intensified and diversified only after 1980 and to a greater extent after 1990. New immigrants came from a much wider range of countries outside of Europe, with large numbers of Indians, Mexicans, Southeast Asians, Africans, Chinese, and Koreans in the city and suburbs. They entered a new regional economy, with the bulk of jobs dispersed in the suburbs, including high-paid posts in service and scientific sectors like health care, higher education, finance, computers, and pharmaceuticals. These jobs have attracted well-educated immigrants, while working class immigrants have found work in food and domestic service and other low-wage jobs. These trends marked significant changes in immigration to the region and nation, as today’s newcomers are far more diverse socially and economically than the working class immigrants from Europe a century ago.

1980s Immigration

In national context, late twentieth-century Philadelphia illustrated distinct patterns and challenges of newcomer settlement in a low-immigration region that remained largely white and Black and continued to struggle with the legacy of deindustrialization, patterns shared with other Rustbelt regions and re-emerging gateways like Baltimore and Milwaukee. When new immigrants began to arrive in sizeable numbers in the early 1980s, they did not immediately follow local jobs to the suburbs. Instead, most initially settled in the old, economically debilitated urban core, where they found a city divided sharply between Black and white with a small but growing Latino population, primarily Puerto Rican, and an old Chinatown struggling to survive urban renewal. Almost exclusively white suburbs encircled the city. Yet many of the less upwardly mobile descendants of old immigrants remained in the city, vying, sometimes violently, with Blacks for power, turf, and the political upper hand. For new immigrants, the precipitous fall in the city’s population that coincided with deindustrialization meant readily available housing, but often amid racial and economic tension.

Such was the case for the many Southeast Asian refugees resettled in Philadelphia after the Vietnam War. The resettlement agencies tended to find open housing in borderland areas, where the combination of gentrification and job loss had already pushed lower-income residents out. Vietnamese, Cambodian, and other Southeast Asian refugees in Philadelphia often found themselves wedged between struggling African American communities and significantly wealthier neighborhoods. Settled in West Philadelphia, in North Philadelphia’s Olney and Logan sections, and in South Philadelphia, refugees struggled to make an already difficult cultural adjustment amid existing Black-white racial animosity and economic tension. The consequences of life in these borderlands were harsh. According to the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations, Asian Philadelphians comprised roughly a quarter of the victims of interracial incidents in the city in the late 1980s; at the time, Asians comprised only three to five percent of the city’s total population. A small group of Hmong refugees resettled in Philadelphia faced such adversity that they fled the city, mostly for established Hmong settlements in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Yet most Southeast Asian refugees in Philadelphia persisted, increasingly leaving West and Southwest Philadelphia for South Philadelphia and East Camden, where working class Cambodians and Vietnamese still concentrate, while middle-class Vietnamese families more often moved to suburbs like Upper Darby and Cherry Hill.

By 1990 Koreans also made up a sizeable proportion of Asian immigrants in Philadelphia, illustrating different conditions of migration but also some similarities in settlement experiences. Middle-class Koreans, frustrated with opportunities in their own country, took advantage of the 1965 immigration law’s skills-based employment preference system. Others obtained professional training in the United States and remained in the area. Once settled, Korean immigrants sponsored their relatives’ visa petitions, a broad pattern shared with other immigrants. Many Koreans with high levels of education struggled to transfer their credentials or to overcome an initial language barrier, and hence gravitated toward small business ownership rather than professional jobs, often experiencing considerable downward mobility for a time.

Racial Tensions and Tolerance

Korean entrepreneurs helped sustain commercial districts in North Philadelphia, West Philadelphia, Germantown, and the old streetcar suburb of Upper Darby. In each of these areas, Korean storeowners did business with the region’s working-class, especially African American, populations. And like in other cities, where Black-Korean tensions boiled over into riots, conflict sometimes defined relations in Philadelphia. Yet the relationship between Korean storeowners and their clients, as elsewhere, was most often defined by tolerance and civility. In addition to these storeowners, a considerable set of working-class Koreans also migrated to the city, often through family sponsorship. Most worked in the local garment industry, in laundries, or in small stores, frequently employed at Korean- or Chinese-owned enterprises. Many remain in the city, but more have moved to the suburbs of Delaware County, Cheltenham, or North Wales and nearby towns in central Montgomery County. Since the 1990s, Dominicans have bought and run a large portion of Koreans’ inner city stores.

Also fueling the growth, diversification, and suburbanization of the immigrant population in Philadelphia, a diverse mix of immigrants and refugees arrived from Africa, hailing from over thirty countries with Liberia and Nigeria the largest groups in the region. Highly educated Africans began arriving soon after the 1965 immigration law was passed, and many went on to sponsor the migration of family members. Beginning in the 1980s and continuing in the new millennium, first Ethiopian and Eritrean refugees, and then people displaced by wars in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Sudan, settled in the metropolitan area. Most came from large African cities and settled in West and Southwest Philadelphia, Delaware and Newcastle Counties, and Trenton, while some Sudanese moved to Northeast Philadelphia.

Black immigrants and refugees further illustrated the complexity of newcomers’ diversity of experiences. Although African immigrants to the United States had the highest educational attainment of any other immigrant group, they struggled on the whole to transfer their skills to the U.S. Africans in Philadelphia established employment niches in nursing homes, home health-care for the elderly, parking lots, and taxi service. Liberians, Sierra Leoneans, and later Haitians were granted Temporary Protected Status, meaning the U.S. government expects them to ultimately return to their countries, adding to an already diverse range of legal statuses. African and Caribbean immigrants and refugees largely settled in Black neighborhoods, suffering most of the same ill effects of segregation and discrimination as their African American neighbors. Pan-African organizing and civil society, however, succeeded in forging a politics of shared prosperity by the early twenty-first century, partly in response to violence between young native and immigrant Blacks.

Northeast Philadelphia Immigrants

Joining Black immigrants in reinforcing Black-white segregation were Eastern Europeans who settled in the 1980s and ’90s especially in the predominantly Jewish sections of Northeast Philadelphia and surrounding suburbs. Many were refugees and their families, from the USSR, Russia, and Ukraine. Poles settled in the old Polish enclave of Port Richmond. Albanian Muslims were resettled in Fishtown and South Kensington, overlapping a small Palestinian enclave that had formed after the Yom Kippur War in 1973.

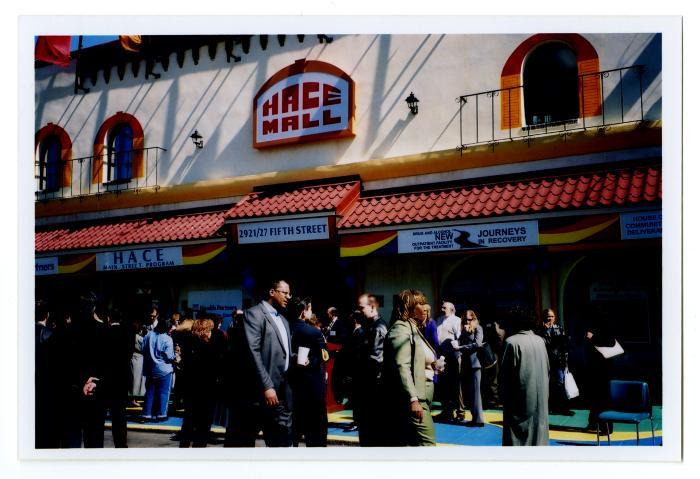

In the 1990s, Indian and Mexican immigrants finally supplanted Italians and Germans as the largest foreign-born groups in the region, as Greater Philadelphia experienced more substantial and diverse immigration continuing into the early twenty-first century. Mexican settlement in South Philadelphia and Norristown signaled the health of the downtown and suburban service economies, including the Center City restaurant scene and regional construction boom. The region’s South Asian population, predominantly Indian, mostly came for middle class jobs and higher education, settling in Northeast Philadelphia, King of Prussia and other suburbs. Some working class Indians and Bangladeshis also settled in West Philadelphia and Millbourne, a tiny borough in Delaware County and the first majority-Indian municipality in the U.S. Chinese immigration in this era also included both professional and working classes, who lived in the historic downtown Chinatown and “satellite Chinatowns” in Cherry Hill and South and Northeast Philadelphia. Like Africans, these groups illustrated the bifurcation of immigrants’ economic and residential experiences in the late twentieth century.

In 2008 the city of Philadelphia gained population for the first time since the 1950s, propelled mainly by immigration, which also helped reverse population loss in Norristown and other older suburbs and towns. According to a Brookings Institution report that year, among similar metropolitan areas Philadelphia had “the largest and fastest growing immigrant population.” Immigrants made up roughly nine percent of the region’s population, still lower than the national average though the area was an increasingly important destination. Many of its foreign-born moved to the area after originally having settled elsewhere in the U.S., especially the New York region, often choosing Greater Philadelphia because of its lower costs of property and starting businesses compared to other major urban centers.

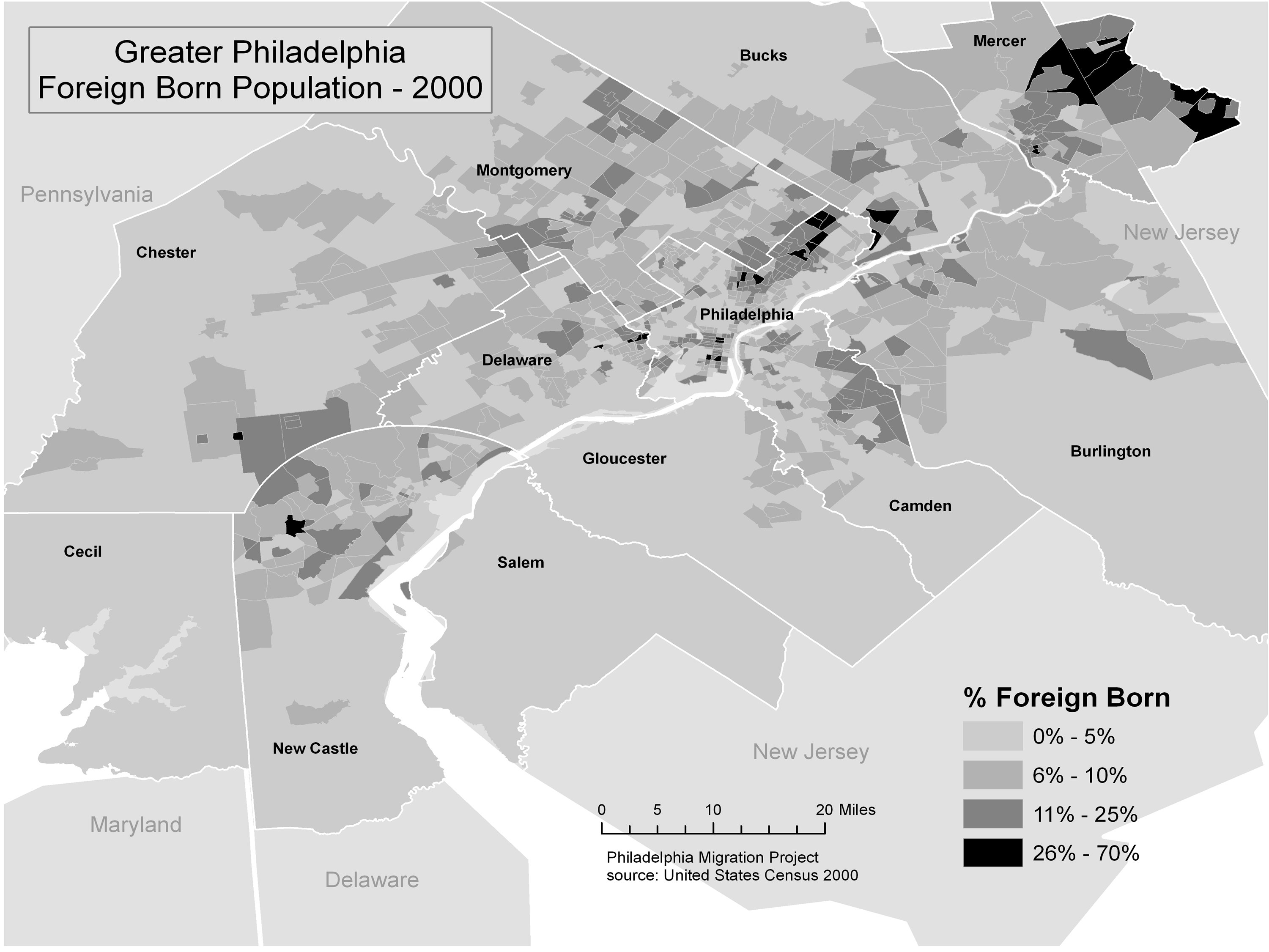

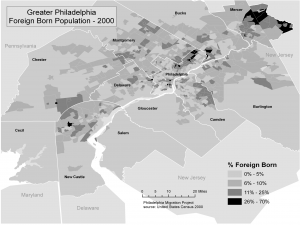

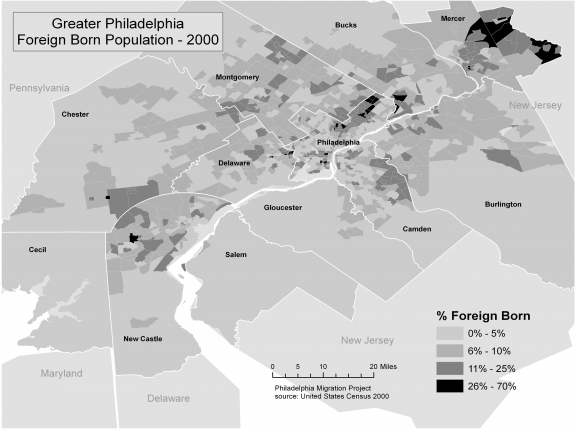

By 2000, the map of foreign-born population in the region illustrated major centers and corridors of settlement. Higher-income immigrants clustered along the route 202 corridor with its concentration of jobs in pharmaceuticals and other technology sectors, running from the suburbs of Trenton in the northeast corner of the region to the west-southwest through Bucks, Montgomery, and Chester counties and turning south to the suburbs of Wilmington in Newcastle County. Super-diverse, “global neighborhoods” had emerged in South and Upper North Philadelphia and in Upper Darby just west of the city. As the map shows, since the 1980s a Mexican community helped sustain Kennett Square in southern Chester County as the world capital of mushroom production, as well as agriculture in Bridgeton, Vineland, and other parts of South Jersey.

By 2000, the map of foreign-born population in the region illustrated major centers and corridors of settlement. Higher-income immigrants clustered along the route 202 corridor with its concentration of jobs in pharmaceuticals and other technology sectors, running from the suburbs of Trenton in the northeast corner of the region to the west-southwest through Bucks, Montgomery, and Chester counties and turning south to the suburbs of Wilmington in Newcastle County. Super-diverse, “global neighborhoods” had emerged in South and Upper North Philadelphia and in Upper Darby just west of the city. As the map shows, since the 1980s a Mexican community helped sustain Kennett Square in southern Chester County as the world capital of mushroom production, as well as agriculture in Bridgeton, Vineland, and other parts of South Jersey.

The Immigration Debate

In the early twenty-first century, Greater Philadelphia also became a national center of immigration debates and movements. Beginning in 2001 the city had a “sanctuary” policy of protecting unauthorized immigrants by forbidding local police from asking for immigration papers. In 2003, Norristown passed a law recognizing the Mexican consular identification card for access to municipal services and banks. On February 14, 2006, Independence Mall was the site of the first “Day Without an Immigrant” rally of mainly Mexican restaurant workers. By that spring, headlines juxtaposed large immigrant rights marches against disputes over an “English-Only” sign in the storefront window of the city’s famous Geno’s Steaks. That summer and fall, first the town of Hazleton in the Poconos, then Riverside, New Jersey, and then Bridgeport, Pennsylvania, passed “illegal immigration relief acts” to punish landlords and employers of unauthorized immigrants. Riverside repealed its act when it saw people leave, local businesses suffer, and out of embarrassment from negative national press.

In some ways the recent dynamics of newcomer settlement and debates over immigration recall the era of mass European immigration a century earlier, though much about the new immigration is indeed new. For example, the experiences of recent Mexican immigrants resemble those of earlier generations of Italians, from their roles as cheap labor in booming food and construction industries to the fear they have encountered among receiving communities about housing overcrowding and integration. Yet the legal status of many new working class immigrants was quite different, partly since immigration restrictions barely existed for Europeans a century ago. Receiving communities’ politics of immigration remained fragmented and polarized, yet their responses took new forms. Moreover, newcomers of the early twenty-first century settled in a region with new geographies and structures of opportunity. Finally, the newest immigration was more diverse than older eras of immigration, in every way. It began to push Philadelphia and many of its suburbs beyond the Black-white binary of their twentieth-century population and neighborhood identities.

Daniel Amsterdam is Assistant Professor of History at the Georgia Institute of Technology. Domenic Vitiello is Assistant Professor of City Planning and Urban Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. This essay is based partly on their work with colleagues in the Philadelphia Migration Project at the University of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Northeast Philly woman honored by NEA for reviving Ukrainian needlework (WHYY, July 3, 2014)

- Looking at SW Philly fire tragedy through the eyes of the city's Liberian community (WHYY, July 15, 2014)

- Liberian Women's Chorus for Change using music to heal in Southwest Philly (WHYY, July 17, 2014)

- Demonstrators, opinions clash over Central American kids coming to U.S. (WHYY, July 18, 2014)

- 117 immigrant children placed in Delaware homes (WHYY, July 25, 2014)

- Immigrants in Pennsylvania: the numbers and the programs to keep ‘em coming (WHYY, December 15, 2014)

- Immigration activists call on Pa. to stop detaining children at Berks facility (WHYY, September 15, 2015)

- Helping immigrants with business needs, Philly hopes to gain in translation (WHYY, February 19, 2016)

- After visit from Homeland Security chief, Kenney stands firm on Philly 'sanctuary city' status (WHYY, May 4, 2016)

- High court impasse frustrates immigrant families yearning to 'come out of the shadows' (WHYY, June 24, 2016)

- Philadelphia to host immigration forum on day one of DNC (WHYY, July 13, 2016)

- Sanctuary cities bill clears Pennsylvania Senate (WHYY, February 8, 2017)

- National Museum of American Jewish History exhibit links 1917 to today's debate on immigration (WHYY, March 16, 2017)

- In Philadelphia, Haitians celebrate heritage and seek U.S. protection (WHYY, May 19, 2017)

- U.S. increasingly arrests unauthorized immigrants without criminal past in Philly region (WHYY, May 26, 2017)

- Philadelphia complying with immigration regulations, city tells U.S. (WHYY, June 22, 2017)

- Pew report: Immigrants give Philly a population boost (WHYY, June 7, 2018)

- Kenney ends Philly police data-sharing deal with ICE to protect immigrants (WHYY, July 27, 2018)

Links

- Welcoming Center for New Pennsylvanians

- Facts About Immigrant New Jersey (Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers)

- Southeast Asian Mutual Assistance Associations Coalition, Inc. (SEAMAAC)

- Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society

- Nationalities Service Center

- U.S.Immigration Legislation Online (University of Washington-Bothell)

- Pennsylvania Immigration and Citizenship Coalition

- Meet the New Immigrants Reviving a Philadelphia Neighborhood (Next City, November 10, 2017)