Library Company of Philadelphia

Essay

With a handful of like-minded associates, the twenty-one-year-old Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) formed a self-improvement club in 1727. By reading, conversing, and improving their minds, members of the Junto believed they would also improve their circumstances, their social position, and their community. Four years later, much the same group institutionalized edification and self-improvement by establishing the Library Company of Philadelphia.

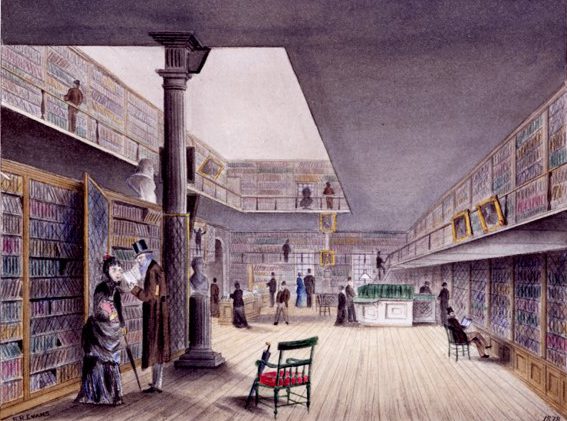

Together, shareholders acquired books that, as individuals, they would not be able to know about or afford. And from the 1730s to the middle of the nineteenth century, this earliest subscription library in the colonies grew into the largest public library in the United States. By the mid-twentieth century it transformed into an independent research library documenting every aspect of U.S. history from the colonial period through the Civil War era and beyond.

The institution supported forward thinking in the spirit of engaged inquiry—knowledge through experience. The first surviving catalog from 1741 lists 372 titles, “best sellers” from the first half of the eighteenth century. Shareholders tended to choose books they considered practical: science, history, or literature more than theology, theater, or classics in Greek, even though the library’s first directors envisioned Philadelphia as “the future Athens in America.” Acquisitions included do-it-yourself builder’s dictionaries and architectural style guides to help Philadelphians emulate London as rebuilt by Christopher Wren (1632–1723). The most expensive early purchase was the six-volume Historical and Critical Dictionary by French philosopher Pierre Bayle (1647–1706), known for its tolerant and rational perspective. By 1770, the library’s collections had expanded to 2,033 books, and the character remained similar, reflecting, as Librarian Edwin Wolf 2nd (1911–91) would much later describe it, “the basic character” of American colonial culture.

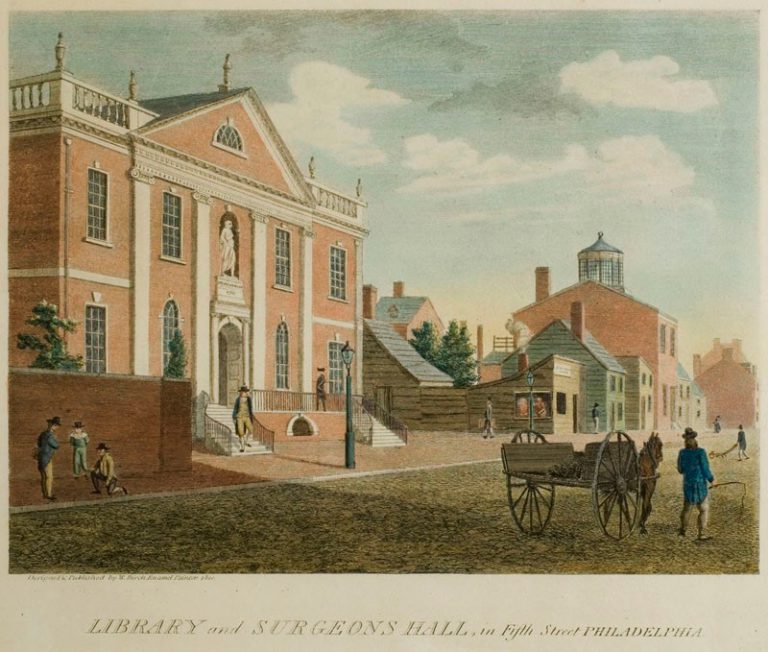

Throughout the eighteenth century, the library was itinerant, though always well-situated, occupying the west wing of the State House in 1740 and the second floor of Carpenters’ Hall by 1773, where it served as the library of the Continental Congress and of the Constitutional Convention. By the 1790s, with more than five hundred members (about a tenth of the city’s households), the library also played a part in the new federal government complex on the State House (later Independence) Square. In the first building of its own just south of Chestnut Street, at Fifth and Library Streets, the Library Company served as the de facto Library of Congress until the government moved to Washington, D.C., in 1800.

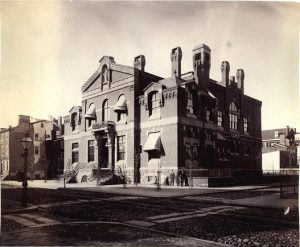

Over the next several decades, the collections outgrew the original building. In 1869, a bequest of books and cash from Dr. James Rush (1786–1869), son of Dr. Benjamin Rush (1746–1813), enabled a much-needed new library. In his will, Rush called for a Center City location, but in a subsequent codicil he left the location to the discretion of his executor. Hoping to keep the Library Company from evolving into a typical urban public library, Rush’s bequest banned “every-day novels, mind-tainting reviews, controversial politics,” and daily newspapers. Library directors had little choice but to accept the quirky terms and out-of-the-way location, accepting a new Greek Revival temple at Broad and Christian Streets (later the Philadelphia High School for Creative and Performing Arts). To maintain a presence in Center City, library directors commissioned architect Frank Furness (1839–1912) to design another building eight blocks to the north at Juniper and Locust Streets.

After the Free Library of Philadelphia was chartered in 1891, the Library Company’s public role faded further and its purpose grew marginal. The Great Depression diminished the endowment, and during World War II the library briefly operated as a branch of the Free Library. By the middle of the twentieth century, it had become clear, as Librarian James N. Green (b. 1947) later wrote, “a new raison d’etre had to be found, or the library would cease to exist.”

With virtually all the books acquired in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries still on the shelves, the library chose to move away from the circulating library model and transform into a research institution. Beginning in 1955 under the direction of Edwin Wolf 2nd, the library articulated the scope of its main interests as American history and culture up to about 1880. Wolf guided relocation back to Center City in a new building adjacent to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, with a modern reading room and environmentally controlled book stacks. Now side by side, the two institutions formed an unprecedented collaborative, collection management agreement in the mid-1960s—possibly the first in the city’s cultural community.

The Library Company’s collections continued to grow into one of the best in the nation to study early American intellectual history, enabling new ways of seeing the past. By 1969, with a broad and growing interest in African American history, Edwin Wolf decided to make that an institutional priority. A groundbreaking exhibition, Negro History: 1553–1903, was followed by a printed bibliography with 16,500 entries that became a classic reference. Ongoing acquisitions in African American history added thousands more books and graphics, transforming an interest area into one of the library’s strongest single subject areas. Over time, the library applied the same interpretive focus and collecting technique to the history of women, U.S. education, philanthropy, agriculture, and natural history, as well as Philadelphia prints and photographs and other areas of interest to researchers.

Into the twenty-first century, the Library Company continued to encourage scholarly use of its collections by offering fellowships for research within the scope of its collections. It mounted changing exhibitions of materials from the collections in the gallery, often accompanied by printed catalogs and online exhibitions. The library also sponsored scholarly symposia and published the proceedings, and its online catalogs and databases enabled access to more than five hundred thousand books and seventy-five thousand graphic materials anywhere, anytime. The city’s oldest cultural institution embraced the digital age while rededicating itself to stewardship of the past and continued sharing of useful knowledge with both scholars and the public.

Kenneth Finkel, professor (teaching/instructional) in American studies and public history at Temple University, served as curator of Prints and Photographs at the Library Company from 1977 to 1994. He is a regular contributor at the PhillyHistory blog. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University.