Immigration (1870-1930)

By Barbara Klaczynska | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

During the national explosion of immigration that took place between 1870 and the 1920s, the Philadelphia region became more diverse and cosmopolitan as it was energized by immigrants who indelibly changed the character of the places where they settled. With its reputation as the “Workshop of the World,” Philadelphia attracted immigrants to jobs in industry, construction, and its vibrant port. Immigrants spread through the city and region, but they were more likely to organize in small clusters drawn to centers of employment, churches and synagogues, schools, shops, friends and families. The upsurge lasted until the United States government enacted unprecedented restrictions on immigration in 1924.

By the 1870s, Philadelphia’s diverse population included the descendants of earlier immigrants, including the English, Swedes, Germans, and Dutch. The city also had one of the largest African American populations of any northern city and overflowed with the first and second generation of Irish immigrants whose numbers had increased dramatically with the 1840s potato famine. Into this already-diverse region new waves of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe, China, Latin America, and the Caribbean arrived. Philadelphia neighborhoods changed in response to the increasing numbers of arriving immigrants as particular ethnic groups came to dominate areas that had once been mixed. Nevertheless, Philadelphia was marked by the scattering of ethnic groups throughout the city and the region; for example, the city had eight different Polish parishes in different neighborhoods.

Philadelphia is commonly described as a “low immigration city” because its proportion of foreign-born residents lagged behind other cities. While New York had a 40 percent foreign-born population between 1870 and 1920, and Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Chicago were even higher, Philadelphia reached its peak of 27 percent foreign born in 1870. In 1910, Philadelphia, with a population of more than a million and a half, had a foreign-born population of about 25 percent, still well below the median that year for all major cities (29 percent). Still, at the turn of the twentieth century Philadelphia was the third-largest city in the United States and the total number of immigrants surpassed most other American cities. In addition to newcomers from abroad, the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of earlier immigrants sustained distinct religious and cultural traditions.

Philadelphia as Refuge

Philadelphia became a home for immigrants fleeing political turmoil, persecution, and drastic poverty who came to places where they could find relatives, countrymen, churches, synagogues, and agencies able to understand and in some cases welcome them. They found employers who spoke their language and needed workers with their skill sets, such as leather workers from Poland, lace makers from Ireland, and cigar makers from Puerto Rico. The push and pull combined to make Philadelphia a receptive immigrant destination.

The number of foreign born in Philadelphia grew steadily between 1870 through 1920, even though the percentage of foreign-born dropped from 27 percent in 1870 to 22 percent in 1920. Census figures illustrate how new migrations changed the ethnic composition of the city and region. In 1890 the largest group of immigrants in Philadelphia was the Irish, numbering 110,935 or 41 percent of the foreign-born population. German immigrants numbered 74,971 and made up 27.8 percent of the total foreign-born population. By 1920, Philadelphia’s foreign-born numbered 400,744 with the leading groups being Russians (95,744), Irish (64,500), Italians (63,223), Germans (39,766), Poles (31,112), English (30,866), Austrians (13,387), Hungarians (11,513), Rumanians (5,645), and Lithuanians (4,392). Most of the Russians and many other Eastern Europeans were Jews who fled persecution.

The number of Italians in Philadelphia skyrocketed from only 516 in the 1870 census to 18,000 by 1900. The surge continued with 77,000 Italian immigrants and their children living in Philadelphia in 1910, 137,000 in 1920, and 182,368 by 1930–making Italians the second-largest ethnic group in Philadelphia. By 1930, more than two-fifths of all foreign-born residents in the city of Philadelphia were Russian Jews (22.5 percent) or Italians (18.3 percent). These two groups made up almost as much of the larger region’s foreign-born residents (Italians, 19.7 percent, and Russians, 18.4 percent). Italians settled outside the central city more often than other groups, such as the Irish, who made up 13.4 percent of the city’s foreign born but just 8.3 percent in the region.

By 1900, only 5.5 percent of Philadelphia’s immigrants were German, but as the city was at that time the third-largest in the United States, there were more German-born residents than in traditionally identified German strongholds in Buffalo, Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and St. Louis. In 1901, Philadelphia activists founded the National German American Alliance, which served as a key organization to encourage resisting assimilation. As historian Russell Kazal has shown, lively German immigrant communities along Girard Avenue, which included churches, shops, and social clubs, helped sustain that identity. Kensington in eastern North Philadelphia became a place where German immigrants lived along with Irish, Polish, and other native born and immigrant groups who found work in the local mills.

Social Clubs and More

Immigrant communities placed their indelible marks on Philadelphia’s neighborhoods and the city as a whole. The immigrants established social clubs (such as the Venetian Club for Northern Italians in Chestnut Hill), fraternal organizations for men and women that provided insurance and social opportunities (such as the Union of Polish Women in America), and banks throughout the city. They operated bakeries, groceries, restaurants, travel agencies, and shipping services originally designed to cater to their fellow immigrants but in some cases serving the entire communities where they were located. The Jesuit priest Father Felix Joseph Barbelin, S.J., established Saint Joseph’s Hospital on Girard Avenue as a hospital to serve Irish immigrants while other ethnic groups established health services for their populations in the twentieth century. The Drueding family brought an order of German sisters to America to operate their North Philadelphia workers’ infirmary, which developed into the Holy Redeemer Health System.

Immigrant groups settled throughout the region. Germans and Poles who were farmers in their homeland moved into small farms throughout the metropolitan region. Immigrants also were attracted to mill towns and smaller industrial cities including Camden, Chester, Norristown, Pottstown, and Trenton, where men, women, and children could find work. African Americans migrating from the South arrived in some of these places, including Camden and Chester, in large numbers at the same time, drawn by employment opportunities and family networks.

Initially, many of the immigrants lived in the inner core of the city but by the early twentieth century many German, Irish, and other European immigrants moved along with native-born citizens to the suburbs. It is possible to trace the mass movements of ethnic groups to the near and, later, far suburbs of the city. For example, Germans and Jews from North Philadelphia moved to Elkins Park and Melrose Park north of the city; Italian, Polish, and Jewish residents of the river wards crossed the river into South Jersey; and Irish residents of West Philadelphia took a foothold in Delaware County suburbs.

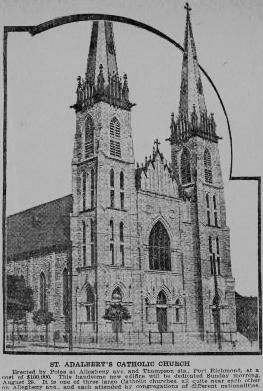

The immigrant groups of this period significantly changed the cultural and religious landscapes of the metropolis. To serve the influx of newcomers, Roman Catholic ethnic parishes took up entire city blocks with churches, school buildings, convents, and rectories. Within four blocks on Allegheny Avenue in Port Richmond, three massive Roman Catholic parishes converged, each created to carry out liturgies in different languages and cultures. Throughout the region, national parishes developed to serve the needs of immigrant groups. These included many operated by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, such as Sacred Heart Parish in Clifton Heights, Delaware County, and Sacred Heart Church in Swedesburg, Montgomery County, for Polish populations, and Saint Ann’s Parish in Bristol, Bucks County, for Italian parishioners. New synagogues served immigrant founders from Russia and Germany. Among Protestant denominations, churches and traditions harked back to German and Swedish origins. Orthodox churches reflected Greek, Russian, Ukrainian, and Armenian traditions.

Second-Largest Little Italy

During this period, South Philadelphia resembled New York’s Lower East Side as large numbers of immigrants arrived right off the boat from Europe or by train from New York or Boston. Philadelphia’s Little Italy was the second largest in the country–surpassed only by New York. The unification of Italy in 1870 and the unsettling changes that followed prompted many to leave for other parts of Europe, South America, and North America. As scholars Richard Juliani and Stefano Luconi have documented, Philadelphia’s largely Ligurian colony in 1870 expanded to encompass arrivals from Northern Abruzzi, Molise, Campania, Puglia, Basilicata, Calabria, and Sicily. Sub-national colonies of Italians developed throughout the city and region. Immigrants from the province of Catanzaro, in the Calabria region, lived along Ellsworth Street, while the territory around Eighth and Fitzwater Street was home primarily to people from Abruzzi. These settlers split in even smaller districts in which specific streets had settlers from specific towns in Abruzzi. Italians lived in enclaves of row houses in South Philadelphia and in clusters in West Philadelphia, North Philadelphia, Nicetown, Mayfair, Manayunk, Germantown, Chestnut Hill, and Southwest Philadelphia as well as outside the city in Norristown, Bristol, Strafford, Chester, Conshohocken, Coatesville, Marcus Hook, Narberth, Ardmore, and Bridgeport, and in Camden, New Jersey.

While many Italians came through an elaborate recruitment system of contract labor, immigrants generally were drawn to Philadelphia by their ties with friends and relatives already living in the region and work opportunities in manufacturing and construction. Stonemasons came from Friuli to help build the homes and estates of Chestnut Hill and established an ongoing presence in that area, where their descendants continued to live. Italians worked in the textile and clothing industry, building trades, and railroads. In the clothing industry Italian men and women worked in the shops, but the largest numbers of Italians were found in the contracted home work until the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933 shut down this business. In the 1890s, Italians owned 110 contract clothing workshops out of a total of 600 citywide.

Italians often came as temporary workers with the intention of returning their wages and eventually themselves to Italy once money had been made. However, when they were not able to save the money needed to make the return trip home or once home failed to establish themselves and their families they often chose to return to or remain in the United States.

Italian Parishes Grow

A majority of Italian immigrants and their offspring were Catholic, with distinct parishes for northern and southern Italians. In 1852, the first Italian parish established in the United States, Saint Mary Magdalen de Pazzi near the Ninth Street Market in South Philadelphia, served the early Italian settlers from Liguria and Piedmont in Northern Italy. When Southern Italians began to arrive in the 1890s they were discouraged from attending Saint Mary Magdalen and instead were directed to Our Lady of Good Counsel, Philadelphia’s second Italian parish founded in 1898, a few blocks east. By 1930 sixteen parishes served Italians in various parts of the city–a number that, according to Richard Varbero, reflected not only the optimism of the Catholic Church but also its miscalculations about projected growth and stability of immigrant-ethnic communities.

Philadelphia’s Jewish population dated from the colonial era, but in the late nineteenth century Russian Jews became the largest foreign-born group in the city. Jewish immigrants from Russia, Poland, and other parts of Eastern Europe arrived at the Christian Street wharf and in many cases walked a few blocks to the homes of relatives and countrymen. The Jewish population of South Philadelphia grew from 55,000 in 1907 to 100,000 in 1920. Even though a Philadelphia Housing Association survey reported continuing decreases in South Philadelphia, it remained the most populous Jewish neighborhood in the city, numbering close to 50,000, according to Rakhmiel Peltz.

North Philadelphia, with 50,000 Jewish residents in 1930, was the fifth-largest Jewish section in the city. It developed as a center for Jewish institutional life with social associations, two Jewish colleges, and the Jewish Publication Society. Synagogues began to follow Central and Eastern European, or Ashkenazi rituals in response to new immigrant groups, and to adopt Reform practices. A vibrant shopping area at Marshall Street along the Girard Avenue corridor became a major hub operated by Jewish merchants and patronized by Polish and German Christian customers who shared common languages and tastes.

A variety of organizations addressed the needs of Jewish workers in Philadelphia. Poor working conditions and the presence of Jewish anarchists and socialists made the community a center for labor organizing, leading to workers associations and unions for a variety of occupations including bakers, men’s clothing tailors, and ritual slaughterers who worked in kosher butcher plants. Synagogues, based on the ethnic background of their membership and the types of services performed, included the first Russian synagogue in Philadelphia, B’naa Abraham; Kesher Israel; and the Romanian American Synagogue. Jewish institutions included a Labor Lyceum formed by nine branches of the Workmen’s Circle and the Downtown Orphanage. The Neighborhood Settlement was started at Fifth and Bainbridge to serve Jewish families and stayed there until 1948, when it moved to North Philadelphia, where it again served as an important hub of Jewish life.

New Jerusalem in Port Richmond

Another Jewish community, New Jerusalem in the Port Richmond section of the city, became a destination for Russian Jews who met with discrimination by more established and prosperous Jews of German descent. In New Jerusalem, residents worked as peddlers and rag pickers and began to translate work they had done in the Russian shtetl to occupations such as shoemakers, horseshoers, water carriers, coopers, tailors, leather workers, cigar makers, umbrella repairmen, horseradish vendors, and eventually hardware merchants, dealers in glass, grocers, and dry goods merchants. New Jerusalem established Orthodox synagogues, and the Hebrew Education Society opened a school to teach children English and marketable skills including carpentry, cigar making, and sewing. By 1908, New Jerusalem had 4,000 residents and they remained an important component of this multiethnic community through the 1970s, when the last of the merchants left the area. Russian Jews also moved into North Philadelphia, where they replaced an earlier population of German Jews, who by the early 1900s had begun a migration from their original enclaves to other parts of Philadelphia including Logan, Parkside, Southwest Philadelphia, Strawberry Mansion, and Wynnefield.

As historian Caroline Golab has shown, Polish immigrants clustered throughout the city in small communities in Nicetown, Port Richmond, Bridesburg, and Manayunk, as well as in Conshohocken and Camden. In each of these communities they quickly constructed churches, parochial schools for their children, and networks of institutions and businesses. Many Polish immigrants who arrived in Philadelphia did not remain, but instead quickly traveled to other regions. With little experience in the type of work available in Philadelphia’s textile and clothing industries, they often headed to places offering work they had done in Poland, such as coal mining in central and western Pennsylvania or labor in the steel mills, iron foundries, sugar and oil refineries, leather tanneries, and slaughterhouses in Chicago, Buffalo, Milwaukee, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh.

Although the vast majority of immigrants came from Europe during this period, the Asian Exclusion Acts of 1882 resulted in violence and intimidation in the western United States that drove Chinese immigrants to eastern cities, including Philadelphia. The beginnings of the city’s Chinatown date to this era, when laundries and later restaurants and stores clustered in the area of Ninth and Race Streets.

Caribbean Immigration

Newcomers also came from the Caribbean, although in fewer numbers than from Europe. In the 1890s immigrants from Cuba and Puerto Rico arrived on the same boats that carried sugar and tobacco grown in the islands, according to historian Victor Vasquez. These immigrants worked as cigar makers for firms including Bayuk Brothers, the largest manufacturer of cigars in the area. The Cubans who arrived in the 1890s brought with them experience and interest in the Cuba Libre movement that was working toward Cuban independence and set up political clubs to support the effort. Cigar making continued to offer employment opportunities in Philadelphia through the 1950s and drew additional newcomers as the industry declined in Florida, Cuba, and Puerto Rico.

Spanish speakers clustered in Northern Liberties, where they worked at the local small cigar factories and shopped at Marshall Street. The neighborhood resembled South Philadelphia and New York’s Lower East Side in its density, ethnic diversity, economy, and civil society. To serve Spanish-speakers, the Catholic Church established the Mission of the Miraculous Medal at Old Saint Mary’s Church on Fourth Street as a place of worship and the home for weddings, baptisms, and holy communions. This and other community organizations would help receive the larger migration of Puerto Ricans and other Latino groups that followed after World War II.

Immigrants encountered increased hostility, prejudice, exploitation and violence in America in the early twentieth century. For example, Philadelphia newspapers once committed to praising the Italian immigrants increasingly criticized immigrants in the period leading to the restriction laws in 1924. Italians faced growing prejudice during the Prohibition years when they came to represent organized crime and various “families” came to control narcotics rings, prostitution, bootlegging, and numbers writing in South Philadelphia. The Ku Klux Klan in Philadelphia boasted the third-largest number of initiations in any American city in the interwar years (35,000) and targeted Italian immigrants because they were Catholic, foreign born, and former or current subjects of a totalitarian regime. While upper class Nativists such as Henry Cabot Lodge drew distinctions between Northern and Southern Italians, the Klan attacked all Italians without discernment.

The Immigration Restriction laws in 1924, which exempted migrants from the Western Hemisphere, created opportunities for increased migration from Cuba and Puerto Rico. Cubans and Puerto Ricans found jobs and housing in working-class neighborhoods of Southwark, Spring Garden, and Northern Liberties, mixing with other ethnic groups who had been in these communities for generations. Latin American and Caribbean migrants of the early and mid-twentieth century also settled temporarily in the region for seasonal agricultural work, often brought by labor recruiters. Some also left the city in the summer for Hammonton and other New Jersey farms to pick berries, tomatoes, and other crops.

Between 1870 and 1930, what had been a city and region of mainly Northern Europeans and African Americans became a far more diverse metropolis of residents from Eastern and Southern Europe, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean. While anti-immigrant acts and sentiments persisted, immigrants and migrants including African Americans from the South and Puerto Ricans found ways to live and work together. Although statistically Philadelphia had a smaller percentage of immigrants than other cities, it is clear that the immigrant groups left an indelible imprint, which long continued to influence the region’s people, places, and institutions.

Barbara Klaczynska researches, writes and teaches about urban, ethnic, labor, and women’s history. She teaches at Saint Joseph’s University and Penn State University Abington and works in preservation and interpretation with museums, public gardens, historic houses and sacred places. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Continue to Immigration (1930-Present)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Washington Avenue Immigration Station (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Philadelphia's Italian Market (PhillyHistory.org)

- Immigrant Jewish Philadelphia: School Days (PhillyHistory.org)

- The Jewish Quarter of Philadelphia (PhillyHistory.org)

- 9th Street Curb Market (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- North Marshall Street: Life in a Bazaar (PhilaPlace.org)

- Immigration and Americanization, 1880-1930, Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)