Savings Societies

Essay

The two most prominent forms of savings societies are the mutual savings bank and the savings and loan association, and Philadelphia is the home to the first institution for both. The Philadelphia Saving Fund Society (PSFS), founded 1816, and Oxford Provident Building Association, formed in 1831, were member-owned cooperatives whose success helped launch two financial industries that would aid millions of Americans saving for a variety of goals, including retirement, starting a business, or the purchase of a home. Savings societies thrived in the Philadelphia region until the 1980s when changes in the regulatory environment led to increased competition with other financial industries. The resulting turmoil caused PSFS and dozens of savings and loans to cease operations, and by the end of the twentieth century only a handful of savings societies remained in business.

The ideals and operating principles for savings societies came to America from England and Scotland, where they originated around the turn of the nineteenth century. Designed as self-help institutions, both savings banks and savings and loans assisted people of modest means in achieving long-term financial goals by promoting habits of systematic savings and mutual cooperation. Significantly, people often joined either of these businesses for a specific goal—savings bank members tended to save for the expenses associated with illness, retirement, or death, while savings and loans attracted people who wanted to purchase a home. Members made weekly or monthly deposits that the managers accumulated and invested for their benefit. Savings banks’ funds were invested in low-risk securities like government bonds in order to preserve capital and earn steady income. Savings and loans, however, used their funds to make mortgage loans to the members, which were repaid with interest over time. Because the members of both institutions shared in any profits, it was in the interest of all to stay current on their deposits and payments. At the same time, because these profits were credited to their accounts, members earned compound interest on their savings.

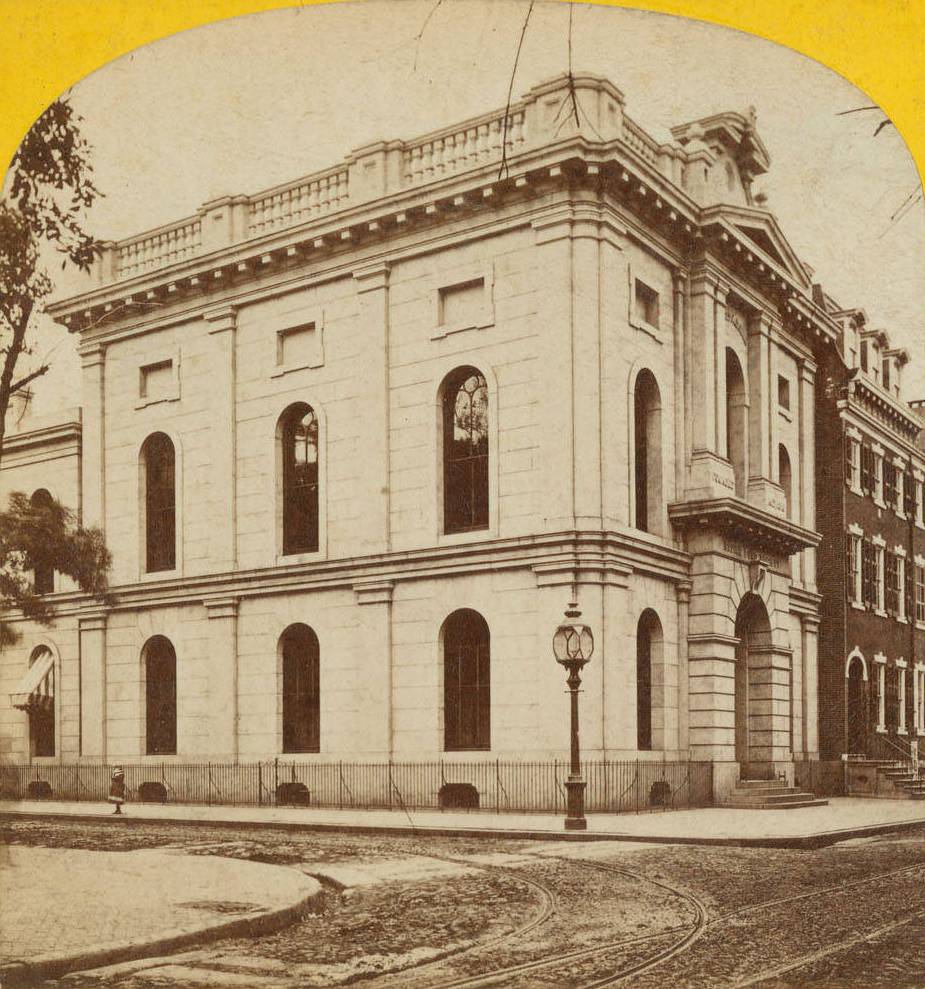

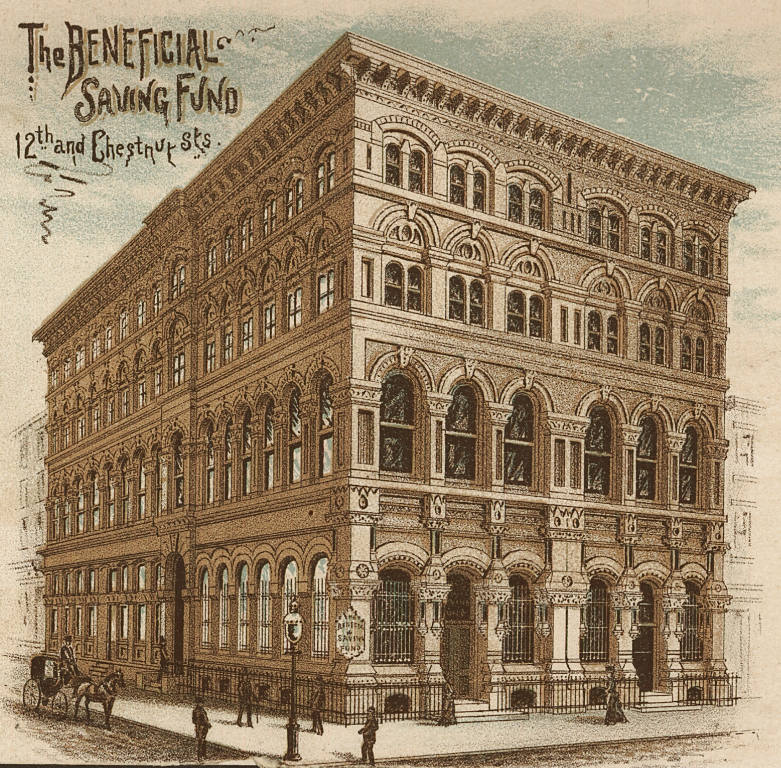

In late 1816, Condy Raguet (1784-1842), a merchant and diplomat, met with several of Philadelphia’s other prominent social and business leaders to organize PSFS. It opened its first office at 22 S. Sixth Street with the express goal of encouraging in Philadelphia’s poor and working classes the practice of regular savings. In 1818, PSFS made its first mortgage (for $7,000) to renowned architect William Strickland (1788-1854), and as word of its reputation as a safe repository spread, the institution grew. By 1850 it had more than 10,000 members, including men and women, white and African American. The first depositor was, in fact, Raguet’s African American servant Curtis Roberts. By 1916, PSFS had the largest number of depositors of any savings bank in America, and was the second largest in terms of deposits. In addition to PSFS, three other savings fund societies formed in the region: Wilmington Savings Fund Society in 1832, Western Savings Fund Society in 1847 (located on Chestnut between Tenth and Eleventh Streets), and Beneficial Savings Fund Society in 1853 at Thirteenth Street below Market Street. The mutual savings bank idea spread to other states, primarily in the Northeast, and by 1930 a total of 592 savings banks were in operation, controlling assets of nearly $10.5 billion.

1831: Oxford Provident Building Association

In 1831, community leaders in the Frankford section of Philadelphia met to organize the country’s first savings and loan association, the Oxford Provident Building Association. Originally called building and loans or thrifts, these associations had the specific goal of helping the members become homeowners. People joined by subscribing to shares in the association that were equal to the amount needed to purchase a home. They paid for them in regular installments, for a period of seven to twelve years. As these share payments accumulated, members applied for an advance equal to the face value of the unpaid shares that would be used to buy a house; these loans would then be repaid with interest over the same terms as the original shares.

The first loan made by Oxford Provident was to Comly Rich, a lamplighter and comb maker, for $375 to purchase a home at 4276 Orchard Street in Frankford. Interestingly, the first building and loans were supposed to go out of business once the original members had all repaid their loans, but soon associations formed that took in new members on a regular basis, and their numbers multiplied. An 1893 federal survey showed that Philadelphia had the largest number of thrifts of any city in the country (more than 400), and their work in helping working-class people buy houses contributed to Philadelphia’s reputation as the “City of Homes.” Like savings banks, the thrift industry spread to other states. By 1930 there were 11,777 savings and loans in operation nationwide, and these small neighborhood businesses controlled $8.8 billion in assets.

One of the significant aspects of this early development of savings societies in Philadelphia was their broad appeal to all elements of the working classes. Both mutual savings banks and savings and loans encouraged men and women to join, and by the early twentieth century many of these institutions (of which PSFS was one of the first) had created special programs to enable children to save. At the same time, savings and loans often formed to serve specific neighborhoods or ethnic communities, a trend reflected in such names as the Thirtieth Ward Building and Loan and the Shamrock Building and Loan. In the 1920s, minority-owned thrifts appeared to address the needs of the city’s growing African American population; and by the end of the decade, Philadelphia had 36 such associations, the most of any city in the country. The oldest of these was the Berean Building and Loan Association founded in 1888 at the Berean Presbyterian Church on South College Avenue.

Depression-Era Foreclosures

The Great Depression took a significant toll on Philadelphia’s savings societies, just as it did on all financial institutions. As members fell behind on their share payments and associations had to foreclose on delinquent loans, more than half of all building and loans in the city went out of business. While Philadelphia’s four major savings banks survived the decade, each experienced difficulties, like deposit runs, that tested the mutual spirit of these businesses. One bright spot during this decade was the opening of the PSFS Building in 1932 at 1200 Market Street in downtown Philadelphia. The 36-floor building is considered the first modern skyscraper in America and included design features that were a stark contrast to traditional bank buildings, including PSFS’s old headquarters at Seventh and Walnut Streets. Based on the new “international style” of architecture, the PSFS building was sleek and streamlined, with identical glass-walled floors wrapped around a T-shaped steel skeleton. A 27-foot, red neon sign on top spelled out PSFS and could be seen for miles.

The return of economic growth in the 1950s and 1960s was especially good for savings societies. While there was not a significant increase in the number of new institutions, the surge in new housing construction (especially in the suburbs like Levittown, Pennsylvania), as well as an increase in the number of branch offices, caused existing savings and loans and savings banks to grow significantly larger. This period of prosperity came to an end in the 1970s as unprecedented increases in interest rates and inflation led to the first significant number of bank failures since the 1930s. Among these was First Pennsylvania Bank, Philadelphia’s oldest bank, which was bailed out by regulators in 1980.

Because of these problems, Congress passed two laws, the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 and the Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982, which significantly deregulated all financial industries and gave both savings banks and savings and loans broad new lending powers. One effect of these new laws was that many Philadelphia savings societies entered new areas of business, with PSFS being arguably the most aggressive in this type of expansion. It merged with Western SFS in 1982, converted from mutual to stock ownership in 1983, and two years later acquired several savings and loans in Florida and the mortgage lending operations of General Electric Credit Corp. By the end of 1985, PSFS was not only the largest savings bank in the country but as part of Meritor Financial Group had become a diversified financial services holding company with $16.7 billion in assets. Another high-flying institution was Hill Financial Savings in Red Hill, which through aggressive lending and acquisitions had become by 1988 Pennsylvania’s largest savings association with more than $2.2 billion in assets.

Rapid Growth, Then Turmoil

Eventually, the problems associated with the rapid growth of the nation’s financial institutions became evident, as hundreds of banks began to fail across the country. While the majority of savings societies in the Philadelphia region escaped the turmoil, there were several notable exceptions. Among these was the collapse of Hill Financial in 1989, later shown to be due to fraud and mismanagement. It became one of the ten most expensive savings and loan failures in history. The 1990 failure of $5.8 billion Atlantic Financial Savings of Bala Cynwyd was the state’s most severe; both of these institutions were eventually sold to Wells Fargo. The most significant loss, however, was PSFS, seized by federal regulators in December 1992 and sold to Mellon Bank. While PSFS ceased to exist, the iconic PSFS building remains a part of the city, having begun a new life in 2000 as the Loews Philadelphia Hotel.

Despite the turmoil and consolidation of the 1980s and 1990s, the Philadelphia region is still home to several billion-dollar savings institutions. These include Beneficial Mutual Savings Bank (successor to Beneficial SFS) and Wilmington Society for Savings FSB, as well as Firstrust Savings Bank, Fox Chase Bank, and First Savings Bank of Perkasie, all of which were originally founded as mutual savings and loans or savings banks prior to World War II.

David L. Mason is an Associate Professor of History at Georgia Gwinnett College, Lawrenceville, Georgia, and has written extensively on the savings and loan industry. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University