Abolitionism

By Richard S. Newman | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Few regions in the United States can claim an abolitionist heritage as rich as Philadelphia. By the time Boston abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison (1805-79) launched The Liberator in 1831, the Philadelphia area’s confrontation with human bondage was nearly 150 years old. Still, Philadelphia abolitionism has often been treated as a distant cousin of the epic nineteenth-century antislavery struggle. The milestone 2013 documentary The Abolitionists (PBS), for example, celebrated Garrison as the antislavery struggle’s first great innovator. Before him, the documentary declared, there was barely an abolitionist movement anywhere in America.

Perhaps it is fitting that a place long associated with Quaker circumspection ceded the abolitionist spotlight to other locales. But Philadelphia’s ambivalent relationship to the abolitionist struggle, particularly during the nineteenth century when the movement became more diverse and aggressive, also explains its marginalized status. The city had vast economic ties to the South and Atlantic world, connecting Philadelphians to the mighty engine of slavery. Brotherly Love was not always accorded to racial reformers – particularly African Americans and women. For a city steeped in notions of tolerance, that is a difficult reality to confront.

For many years, Philadelphia abolitionism was a story of firsts. The 1688 Germantown Protest, which challenged the Society of Friends to treat African-descended people as brethren and not bondsmen, was the first formal protest against slavery in North America. While generations of Quakers gained wealth from both slaveholding and slave-derived commerce, the Philadelphia region soon became a seedbed of abolitionist thought. By the early 1700s, monthly meetings stretching from Burlington in West Jersey to Chester south of Philadelphia began debating slavery’s morality. The visible saints of this inaugural abolitionist wave – Ralph Sandiford (1693-1733) , Benjamin Lay (1677-1759), John Woolman (1720-72), Anthony Benezet (1713-84) – rejected bondage as a necessary part of the modern world, but they were not always popular, even within the Society of Friends. Yet by crafting printed antislavery discourses steeped in secular as well as sacred tones, they also charted new directions for humanitarian reform. No longer was the righteous figure an inward-looking perfectionist; rather he or she was motivated to improve society too. By the Revolutionary era, when the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting banned bondage, Philadelphia Quakers could look proudly on a long history of abolitionism.

Pennsylvania Abolition Society

The second wave of abolitionism was also defined by firsts. The creation of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society (PAS) in 1775, and its reorganization and expansion in the 1780s, marked the beginning of secular abolitionism in the United States. Agitating for slavery’s end at the state and federal levels, and protecting endangered Blacks in courts of law, the PAS gained a glowing reputation throughout the Atlantic world. Although Pennsylvania’s gradual abolition law of 1780 – the world’s first such statute, which liberated enslaved people born after the law’s passage at 28 – did not rely solely on PAS agitation, it drew from the matrix of ideas established by Benezet and his abolitionist colleagues. Over the next several decades, the group perfected legal and political lobbying by gaining support from respectable figures such as William Rawle (1759-1836), David Paul Brown 1795-1872), and Evan Lewis (1782-1834), noted lawyers all. With the American Convention of Abolition Societies, a biennial meeting of gradual antislavery groups created in 1794, often convening in the City of Brotherly Love, Philadelphia was again an abolitionist stronghold.

Yet cracks emerged by the early 1800s. While the PAS aided many African Americans, the group failed to forcefully condemn the rising colonization movement, which supported Black exportation as a means of encouraging southern manumission. Popular in the North as well as the South, colonization deemed free Blacks anathema to white liberty. Still, the PAS did not launch an anti-colonization campaign – even as African Americans in Philadelphia did. Some PAS members also believed that abolitionism must never endanger the Union, no matter how much slavery expanded. The abolitionist cause sagged.

Hoping to reignite the movement, a third wave of abolitionism washed over the region between the 1820s and 1850s. Drawing energy from Black and female reformers, so-called “modern” abolitionists embraced more aggressive forms of protest. Following in the footsteps of Black founders like Richard Allen (1760-1831) and James Forten (1766-1842), who advocated racial equality but were prevented from joining the PAS (which did not admit its first Black member – Robert Purvis (1810-1898) – until 1842), Philadelphia’s Black abolitionist community supported new abolitionist ventures. These included both The Liberator and the American Anti-Slavery Society (a national organization formed in 1833 in Philadelphia), both of which espoused immediate, uncompensated, universal abolition and no compromises with slaveholders. Names told the tale of this abolitionist transformation, both in Philadelphia and beyond. While old-school “abolitionist” groups like the PAS sought to eradicate the legal institution of slavery, new-school “antislavery” societies rejected slaveholding itself as immoral. While some PASers joined the new antislavery crusade, relations between venerable and modern abolitionists remained fraught.

Black Activism

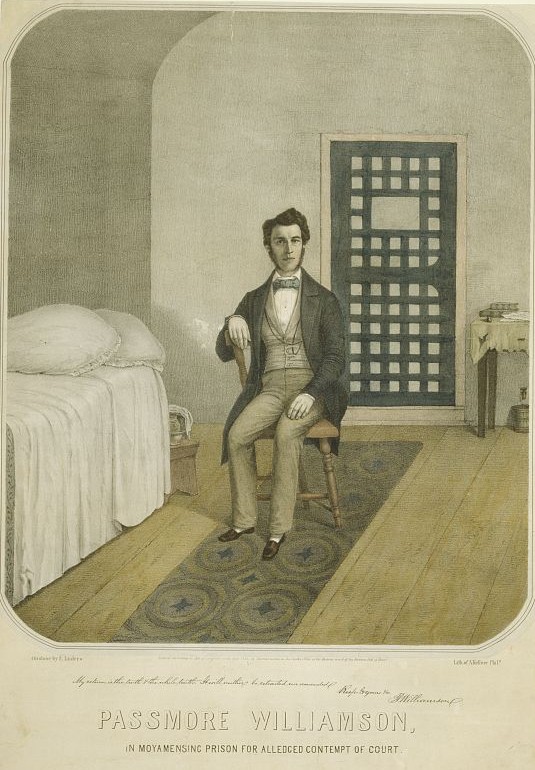

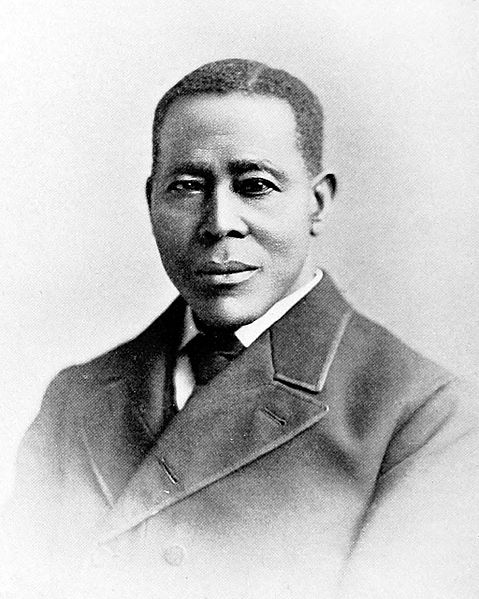

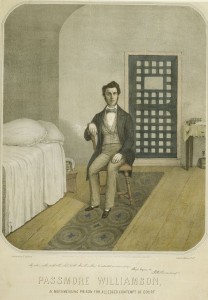

For that reason, Black activists played critical roles in antebellum antislavery circles. Serving as lecturers, fundraisers, and authentic voices of the oppressed, they pictured slavery and racism as twin evils haunting American society. With antislavery contacts stretching from New Jersey to Delaware, Black activists also made the Philadelphia region a hub of fugitive slave activity before the Civil War. In 1837, Black Philadelphians under the leadership of Purvis launched the Vigilant Committee to aid southern runaways, including such celebrated figures as William Crafts (1824-1900) and Ellen Crafts (1826-97) and Henry “box” Brown (c.1816-89). By the early 1850s, when the group was reborn as the Vigilance Committee (now including white members), free Black activist William Still (1821-1902), who hailed from New Jersey, served as its leading figure. Still’s group aided roughly 900 fugitives in the 1850s alone.

Female reformers also emerged as key antebellum abolitionists, locally and nationally. During the 1820s Elizabeth Chandler (1807-34), who worked alongside Garrison at Benjamin Lundy’s Genius of Universal Emancipation, wrote powerfully about female abolitionists’ potential to reshape American antislavery struggles. At nearly the same time, Lucretia Mott (1793-1880) helped build the Free Produce Society (which disavowed slave-derived goods) into a powerful movement aimed at undercutting slavery’s economic standing in northern households. Angelina Grimke (1805-1879) and Sarah Grimke (1792-1873), South Carolinians who rejected bondage after settling in Philadelphia, became perhaps the most prominent female abolitionists in the nation during the 1830s when they began agitating against bondage. Angelina, who married celebrated abolitionist orator Theodore Dwight Weld and subsequently moved to Belleville, New Jersey, became the first woman to address a political body when she spoke before the Massachusetts legislature in 1838.

Women demonstrated their radicalism by establishing Philadelphia’s first integrated abolitionist organization in December 1833: the Philadelphia Female Antislavery Society (PFASS). Predating both the Philadelphia Antislavery Society (1834) and the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society (1837), the group was composed of Black and white women who espoused immediate abolitionism. Between the 1830s and 1850s, members of the PFASS led petition drives, ran antislavery fairs, and served as the organizational backbone of area abolitionism. Little wonder that, by the early 1860s, a woman became perhaps the city’s leading antislavery voice: Republican Party activist Anna Dickinson (1842-1932).

Backlash

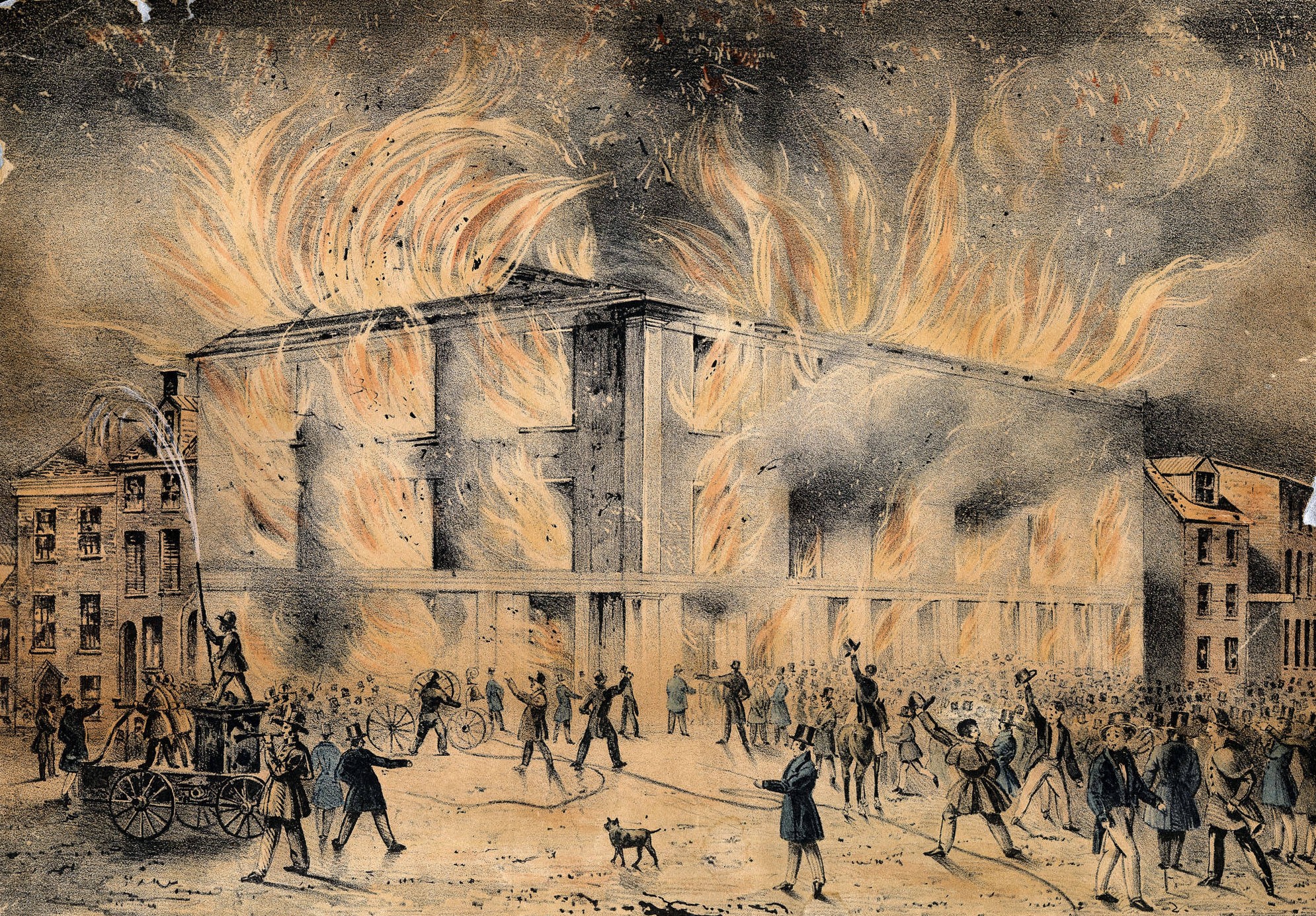

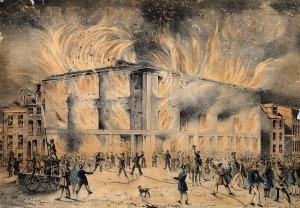

This newly aggressive brand of abolition caused a severe backlash. Indeed, Philadelphia witnessed a series of anti-abolition and anti-Black riots in the 1830s and 1840s that cast a long shadow over racial politics in the city. The infamous burning of Pennsylvania Hall (a newly built abolitionist meeting place) in May 1838 reminded activists that seemingly tolerant Philadelphia supported a violent brand of anti-abolitionism. Viewing race reformers – rather than their foes – as disturbers of the peace, many Philadelphia leaders kept a wary eye on abolitionists for years to come. At both the Great Central Fair of 1864 and the Centennial Exposition of 1876, civic authorities suppressed civil rights activity to prevent a reprise of 1838.

Ironically, while the Civil War vindicated northern abolition, it did not compel Philadelphians to honor living abolitionists in their midst. Instead, distant generations of Quakers became the face of Philadelphia abolitionism for their seeming quietude (a notion forgetting that they too were one-time agitators). It took new rounds of activism to overturn streetcar segregation in Philadelphia (in 1867) and return voting rights to African American men in Pennsylvania (via the Fifteenth amendment in 1870). Perhaps for that reason Black abolitionists like Octavius Catto (1839-71), an egalitarian reformer who was gunned down on election day in 1871, were still viewed as rabble rousers during Reconstruction. More than a century passed before Philadelphians truly reappraised antebellum reformers as civil rights heroes.

Richard S. Newman is Professor of History at Rochester Institute of Technology and the author of Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers (NYU Press). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- American Anti-Slavery and Civil Rights Timeline (UShistory.org)

- Quakers and Slavery (Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College, and Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections)

- Pennsylvania Abolition Society

- Teaching Unit: The Pennsylvania Abolition Society and the Free Black Community (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- William Still: An African-American Abolitionist (Temple University)

- Petitioning for Freedom (National Archives)

- Abolition of the Slave Trade (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- The American Abolitionist Movement Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)

National History Day Resources

- Quaker Protest Against Slavery in the New World, 1688 (Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections)

- Pennsylvania Abolition Society Papers (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, 1780 (Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission)

- Petition Against the Slave Trade, 1799 (DocsTeach)

- Constitution of the Free Produce Society of Pennsylvania, 1827 (Swarthmore College Peace Collection)

- Journal C of Station No. 2 of the Underground Railroad, Agent William Still, 1852-1857 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)