American Philosophical Society

Essay

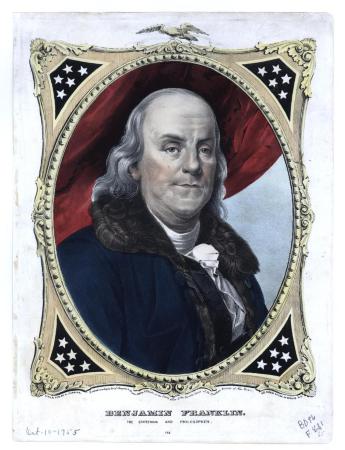

Well before the Declaration of Independence, in 1743 Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) and his friend the Quaker botanist John Bartram (1699-1777) established the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia as a declaration of scientific independence from Great Britain’s scientific domination. The APS developed from a group of local intellectuals keen on expanding human knowledge to serve informally as the national academy of science and national library for a half century after 1790, when the United States capital moved to Philadelphia. Over time, the APS expanded into a multidisciplinary society and prominent institution as members applied their expertise to endeavors ranging from charting unknown territories in the nineteenth century to examining the ethics of scientific advancement in the modern world.

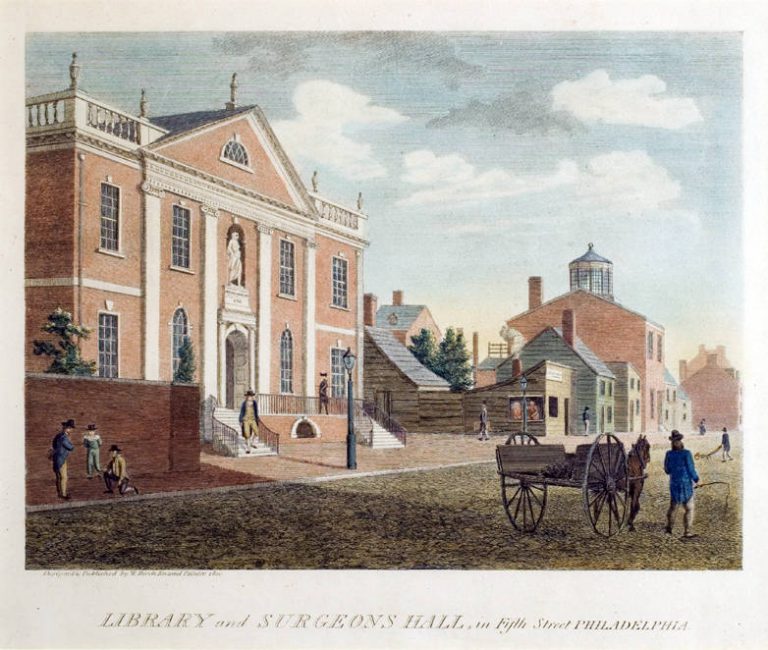

Founded in 1743, the APS was an extension of Franklin’s intellectual club the Junto and an answer to London’s Royal Society. Marking a departure from British science, the founding document of the APS asserted that because the American colonies had matured, intellectuals could employ insights from their North American experience to promote human knowledge. Franklin and Bartram designated Philadelphia as the most logical headquarters because of its location, its easy access by sea, and the vibrant bookish culture fostered by the Library Company of Philadelphia, the lending library Franklin founded in 1731. Philadelphia also had the benefit of Bartram’s unparalleled botanical knowledge, as he collected and identified species of plants found only in North America.

Franklin and Bartram organized the APS to promote advancement in all fields of science. They proposed that there should be no fewer than seven members: a physician, botanist, mathematician, chemist, mechanic, geographer, and natural philosopher, in addition to a president, treasurer, and secretary. Members would meet once a month to conduct experiments in brewing, navigation, and agriculture among other subjects. Yearly membership dues (a Spanish piece of eight) funded the cost of experiments and the publication of the society’s findings, both for distribution among society members and abroad.

The APS quickly became much more collaborative than independent as it became an important international link in the exchange of scientific information. Members such as Bartram maintained ties with their British counterparts and sent specimens overseas, even during the Revolutionary War. From its earliest days, the APS made scientific inquiry a matter of international diplomacy as it elected members from around the world. The first international member of the society, elected in 1768, was the French naturalist and cosmologist Georges-Louis Leclerc (1707-88), followed a year later by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-78). As its first female member, inducted in 1789, the APS chose the president of the Imperial Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, Princess Yekaterina Dashkova (1743-1810).

Building a Reputation

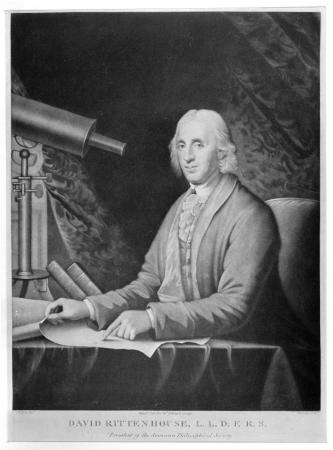

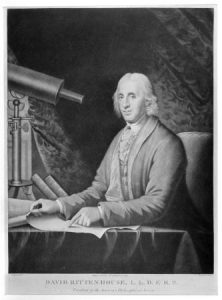

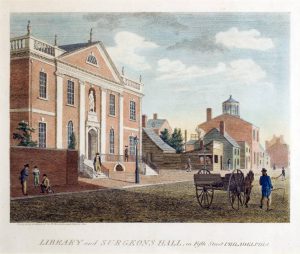

In 1769, a merger with another scholarly society in Philadelphia, the American Society for Promoting Useful Knowledge, gave the APS new vigor and initiated a series of scientific activities that solidified its mission. A crucial first step in establishing the APS as a reputable scientific authority occurred in the same year when David Rittenhouse (1732-96) observed by telescope the transit of Venus. His findings, with other observations around the globe, helped to determine the distance of Earth from the sun. Rittenhouse’s results were published in the APS’s Transactions of 1771 and distributed by Franklin across Europe, putting Rittenhouse’s findings on par with those of the Royal Society in London. In 1770, gifts from Thomas Penn (1702-75), members, and from scientific societies in Dublin and London established the APS Library.

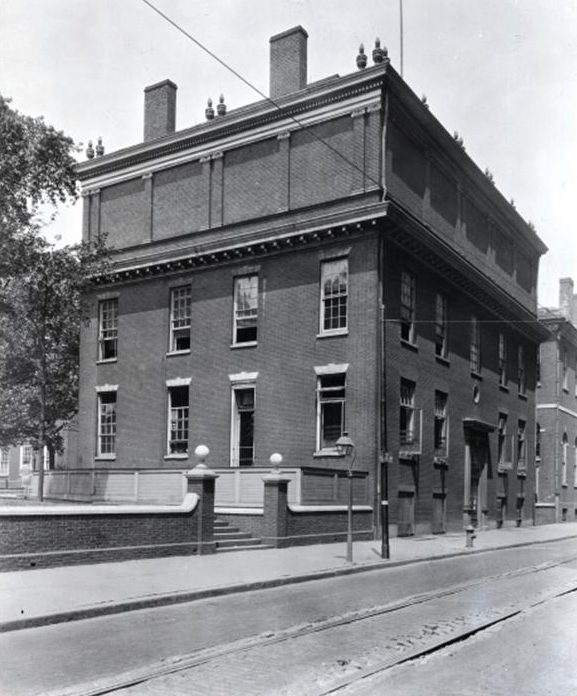

In 1783, the APS sought to further secure its future by voting to build a headquarters, a task completed in 1789. Through a combination of members’ donations and a loan from Franklin, Philosophical Hall was constructed on Fifth Street adjacent to the Pennsylvania State House (later Independence Hall) under the direction of Samuel Vaughan (1720-1802), a friend of Franklin. Vaughan’s sense of style was also responsible at the time for gardens around Philadelphia, including that of the State House, and he designed the garden of another member of the APS: George Washington (1732-99) at Mount Vernon. With its new building, the APS also became a resource for public access to the sciences. Member Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) housed his Philadelphia Museum at the APS from 1794 to 1811, and the University of Pennsylvania also used its space for five years beginning in 1789.

During and following the 1790s, when Philadelphia served as capital of the United States, the APS played a significant role in scientific activities and innovations of the early nation. As U.S. president, APS member Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) sent Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) and William Clark (1770-1838) to Philadelphia to study with other APS members, including Dr. Benjamin Rush (1746-1813), to prepare for their cross-country expedition in 1804. The APS helped to sponsor the mission, and in return the explorers contributed a huge bank of new scientific knowledge on botany, zoology, geography, and ethnology from their travels. Just as their founder Franklin was a leading statesman as well as a scientist, and especially after the success of the Lewis and Clark expedition, APS members tied their research to the service of the state and the expansion of American power. For instance, Commander Matthew Fountaine Maury (1806-73), the “Pathfinder of the Seas,” played a key role in charting the geography of the sea to support an expanding American Navy. In 1862, however, Maury was expelled from the APS for joining the Confederate Navy.

The impact of the APS extended as its members of the APS consulted on the founding of other American scientific and cultural institutions, including the National Academy of Sciences, the Franklin Institute, and the Smithsonian Institution. Ophthalmologist Isaac Hays (1796-1879), a leading member of the APS who advanced a theory of natural selection before Darwin published it in The Origin of Species (1859), was among the founders of the American Medical Association in 1847. APS membership in the nineteenth century included such prominent scientists as Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), Charles Darwin (1809-82), the Swiss-born Louis Agassiz (1807-73) and his wife American-born Elizabeth Cabot Agassiz (1822-1907), Louis Pasteur (1822-95), and Thomas Edison (1847-1931). The scope of the APS also expanded to an additional field of scholarship in 1884 when, inspired by the creation of the American Historical Association, the society began to elect leading historians into its ranks and created a Committee on Historical Manuscripts to promote access to its own rich history.

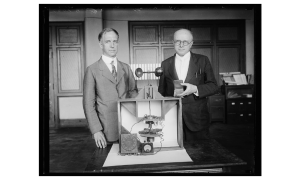

Isaac Minis Mays, Secretary and Librarian

The work of producing manuscript catalogues and calendars of historical documents, as well as editing the Proceedings and Transactions of the APS was taken up by Hays’s son, Isaac Minis Hays (1848-1925), who served as secretary and librarian from 1897 to 1922. An energetic leader, Hays ushered the society into the twentieth century. He improved the quality of the APS library, expanded access to the library for researchers and the public, accomplished a fifteen-year project to bind and catalog the papers of Benjamin Franklin, and created the Franklin Medal to recognize excellence in both science and public service.

The APS continued its transition to a multidisciplinary scholarly organization under the leadership of biologist Edwin Grant Conklin (1863-1952), who served in a variety of APS offices leading to two terms as president in 1942-45 and 1948-52. In addition to members such as Margaret Mead (1901-78) and Albert Einstein (1879-1955), in the twentieth century the society expanded its membership from the humanities: poet Robert Frost (1874-1963), philosopher Isaiah Berlin (1909-97), poet Seamus Heaney (1939-2013), and historian Natalie Zemon Davis (b. 1928). By the early twentieth century, in a departure from the society’s early history of collaboration with the United States military and government, members included scholars whose research questioned institutional power over the individual and reflected on access to justice. They included a philosopher of ethics and human rights, Martha Nussbaum (b. 1947), queer theorists Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (1950-2009) and Judith Butler (b. 1956), and post-colonial theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (b. 1942).

These APS members and many others extended and elevated Philadelphia’s vibrancy, which initially made the city fit to host the society, to a truly international stage. In the second half of the twentieth century, the society also increased its physical presence in its home city. In 1959, across Fifth Street from Philosophical Hall, the APS opened Library Hall, a reproduction of an eighteenth-century structure that originally housed the Library Company of Philadelphia. In 1984 and 2000, the APS campus expanded to include two adjacent former bank buildings on Chestnut Street. Through its rich library and manuscript collection, research grants, and such prestigious prizes as the Magellanic Premium in navigation and astronomy, established in 1786, and the Barzun Prize in history the American Philosophical Society continued its mission of promoting useful knowledge. As affirmed by a mission statement adopted in 2008, the society’s activities sought to “reflect the founder’s spirit of inquiry, provide a forum for the free exchange of ideas, and convey the conviction of its members that intellectual inquiry and critical thought are inherently in the public interest.”

Brooke Sylvia Palmieri is a Philadelphia native living in London, working toward a Ph.D. at the Centre for Editing Lives and Letters at University College London. Her dissertation details the reading, writing, and publication habits of Quakers at the end of the seventeenth century and how they circulated their ideas from London to the British colonies in the West Indies and North America. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Greenhouse of the future on display now in Philly (WHYY, September 7, 2011)

- Franklin feted for 306th birthday (WHYY, January 20, 2012)

- Old tech, new twist: NeoLucida inventor to speak in Philly Thursday (WHYY, November 5, 2013)

- American Revolution libraries to merge into one historical powerhouse (WHYY, June 1, 2019)

Links

- The American Philosophical Society and Western Exploration (Monticello)

- Letter from George Washington to the American Philosophical Society (National Archives)

- American Philosophical Society Member History (American Philosophical Society)

- Meriwether Lewis in Philadelphia (PhillyHistory Blog)

- PhilaPlace: American Philosophical Society (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The Transit of Venus Starts Here (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- David Rittenhouse's map of the transit of Venus, published in the first volume of the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society Philadelphia, 1771. (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- In the Heart of Philadelphia: The Story of Library Hall