Bakeries and Bakers

Essay

Baking, one of the earliest businesses in Philadelphia, did not become a major part of the local economy until the late nineteenth century. It remained a viable industry throughout the region’s history, however, ranging from small neighborhood bakeries to large baking companies with national product distribution.

Philadelphia supported several commercial bakers from the beginning. A list of businesses in the city in 1690 included seven “Master Bakers,” while a 1700 report to the Commissioners of Customs noted that the fertile farmlands of southeastern Pennsylvania allowed for the export of large quantities of bread and flour, staples of Philadelphia’s substantial trade with the West Indies. As the city grew in its early years, bakers were among the many providers of essential goods and services to the expanding population. Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) recalled that one of the first things he did upon arriving in Philadelphia in 1723 was to purchase “three great puffy rolls” from a baker on Second Street.

Philadelphia’s leading trading firms sold large amounts of bread and hard crackers to Caribbean and European customers in the colonial period. The region’s bakeries sometimes had to supply other groups as well. In September 1757, during the Seven Years’ War, the city’s largest trading company, Willing and Morris, wrote to associates in Barbados that it was difficult to procure bread for export because “the Bakers are all engaged in Baking Bread for the different Fleets & Troops in America.” Commercial bakers also did the baking for poorer families that did not have the facilities to bake at home; women would make the dough themselves and pay the local baker a small fee to bake it.

One of the region’s earliest large-scale bakers was Evan Thomas (1690-1746), a Quaker miller who in 1735 bought a tract of land on the Delaware River at the northern edge of Philadelphia County, where he built a very large bake oven. The “Bake House,” as it was known, was a major operation that supplied bread and biscuit to ships that plied the river. When Thomas died, his son Evan (b. 1724) continued the business. Although there is no documentary evidence, tradition holds that the Bake House provided bread for American troops in the area during the Revolutionary War.

Bread for the Troops

Cyrus Bustill (1732–1806) also supplied bread to continental troops during the war. A mixed race African American born a slave in Burlington, New Jersey, Bustill was purchased by a Quaker baker who taught him the trade. After his owner freed him in 1769, Bustill set up a bakery in Burlington, from which he supplied troops in the area with bread. He later moved to Philadelphia, where he operated a bakery on Arch Street above Second Street and became a leader in the city’s African American community.

Germans were among the largest immigrant groups to bring baking traditions from their homeland to the Philadelphia area in the colonial period. German-born Christopher Ludwig (1720–1801) was one of the most successful such immigrant bakers. The son of a baker, he served in that capacity in various militaries in Europe and later received culinary training in London before immigrating to Philadelphia in 1754. Ludwig established a prosperous bakery and confectionary shop in Letitia Court, between Market and Chestnut and Front and Second Streets. Although a wealthy entrepreneur in his mid-fifties at the time of the Revolutionary War, Ludwig nevertheless volunteered for service and in 1777 the Continental Congress appointed him Superintendent of Bakers for the Continental army.

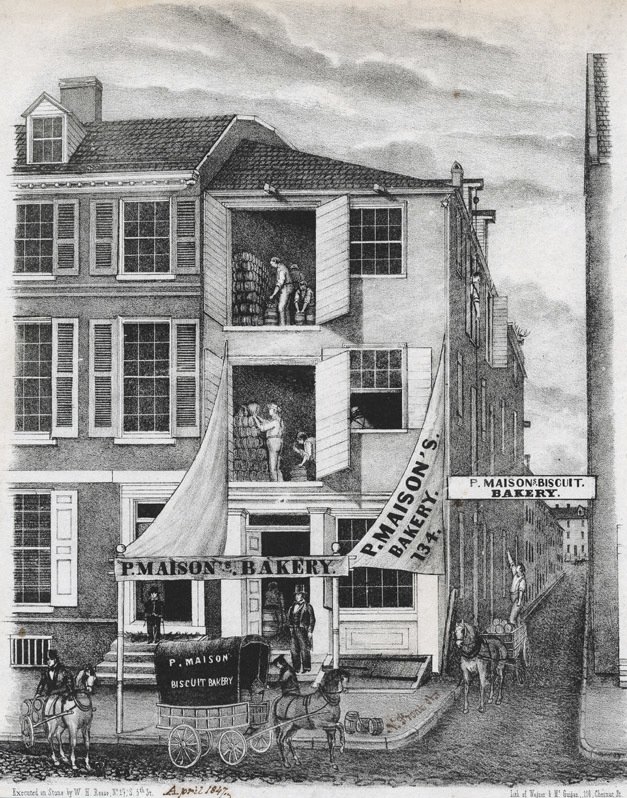

A few large-scale operations notwithstanding, the region’s baking industry was comprised primarily of small shops in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. For example, there were three biscuit makers and four cake bakers among Philadelphia’s self-employed free African American women in 1838. An 1857 report on Philadelphia manufacturers found that while there were many bread makers in the city, only two or three produced enough to be considered wholesalers. A new bread-making firm incorporated in 1856 as the Pennsylvania Farina Company built a large steam-powered bakery at Broad and Vine Streets, but it failed within a few years. The 1857 report noted that baking of pies had recently developed into a considerable business, but that overall, the city’s only major commercial baking activity involved making biscuits, crackers, and ship bread (the latter known as “hard tack”). Nine such establishments operated in Philadelphia in 1857, employing a total of 125 men who made 120,000 barrels of crackers annually.

Biscuits, Crackers, and Cookies

The city’s largest mid-nineteenth-century biscuit and cracker maker was T. Wattson & Sons, which occupied a four-story building on North Front Street. Thomas Wattson (1788–1874) started the business in 1846 and in 1852 sold it to his son-in-law John T. Ricketts (1805–63). One of Rickett’s chief employees was German immigrant Godfrey Keebler (1822–93), who came to America at age ten and at nineteen settled in Philadelphia to learn the baking trade. Keebler operated a small bakery in the city in the early 1840s, moved out of the area for several years, and returned in 1850 to work for Ricketts. In 1862 he went out on his own, first opening a small bakery at Twelfth and Christian Streets in South Philadelphia and then a large factory, Godfrey Keebler’s Steam Biscuit, Cracker and Cake Bakery, at Twenty-Second and Vine Streets. By 1890 Keebler had one hundred employees. He entered into a partnership that year with Augustus Weyl (1835–1926), son of a German-born baker, to form Keebler-Weyl Baking Company, which became one of the nation’s largest cookie and cracker makers.

Another mid-nineteenth century Philadelphia baking company, J.S. Ivins & Sons, rose to prominence on the strength of its cookie products. Founded in 1846 by Job S. Ivins (d. 1894), the company had various locations on North Front Street before moving in 1898 to a large factory on North Broad Street below Ridge Avenue. Ivins produced a variety of cakes and cookies, including Spiced Wafers, a cookie that became a longtime regional favorite after its introduction in 1910.

Vienna Model Bakery of 1876

At the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the Fleishmann brothers, natives of Austria-Hungary who were based in Cincinnati, Ohio, exhibited their “Vienna Model Bakery,” which featured a bread-baking process using packaged compressed yeast cake they had invented. The Fleishmann’s process greatly improved the commercial production of bread, and when the Exposition closed they moved the Model Bakery to Broad Street near Vine Street. From there they expanded into a nationwide baking and restaurant company, while their packaged yeast became widely used in commercial baking, ushering in the era of mass-produced, store-bought bread.

An 1882 census of Philadelphia manufacturers noted that the city was home to 934 baking establishments, employing a total of 3,240 workers, including 2,363 men, 396 women, and 481 children. Curiously, only ten of the establishments were listed as “steam” bakeries; the rest were listed as “hand.” Steam was used to heat baking ovens as well as to power machines that kneaded, mixed, and rolled dough. At a time when most industries were powered by steam engines and many manufacturing processes were automated, baking in Philadelphia was still done primarily by hand. By 1909 Philadelphia boasted 1,208 baking establishments employing 4,598 workers and ranked third in the nation in bread and bakery products.

One of the most successful local baking firms was the Freihofer Baking Company, established by brothers Charles (1860–1942) and William (1858–1932) Freihofer in Camden, New Jersey, in 1893. The company moved to Philadelphia several years later and in 1900 merged into the larger Freihofer Vienna Baking Company. By the mid-1910s Freihofer was one of the largest bread makers in the nation, with nine hundred workers in two large plants in North Philadelphia.

In 1927 Keebler-Weyl merged with a nationwide group of bakeries to form the Union Biscuit Company, whose headquarters were in Chicago. Although part of national conglomerate, Keebler-Weyl maintained major baking operations in Philadelphia. In 1934, the company began making cookies for the Girl Scouts of Greater Philadelphia Council. Local Girl Scout troops throughout the nation had been selling cookies as a fund-raising activity since the 1910s, but Keebler-Weyl was the first commercial bakery to bake and package cookies for the Girl Scouts on a council-wide scale. Other area councils joined the arrangement and Keebler-Weyl became the official baker of what soon came to be known as “Girl Scout Cookies.”

Ethnic Bakeries

The types of baked goods available in the area expanded significantly in the early twentieth century with the influx of large numbers of southern and eastern European immigrants who brought their ethnic baking traditions with them. Italian and Jewish bakeries became especially common, joining German bakeries, which had long been part of the area’s food landscape. Area residents could now purchase a wide range of baked goods in countless neighborhood ethnic bakeries throughout the region.

Local Italian bakers supplied the rolls for Philadelphia’s unique hoagie and cheesesteak sandwiches. The area’s largest roll maker, Amoroso’s Baking Company, was founded by Italian immigrant Vincenzo Amoroso (1862–1927) and his two sons in Camden, New Jersey, in 1904. In 1914 the company moved to West Philadelphia, first to Sixty-Fifth Street and Haverford Avenue and then in 1960 to South Fifty-Fifth Street, where it grew to over four hundred workers. Still family-owned in the mid-2010s, Amoroso’s moved to Bellmawr, New Jersey. In nearby Glassboro, New Jersey, Liscio’s Bakery, another large family-owned Italian bread maker, began in 1994.

German bakers introduced pretzels in the nineteenth century. By the twentieth century pretzels were a signature Philadelphia snack, widely available and popular throughout the area. The Oakdale Baking Company, established in 1903 at North Tenth Street and West Susquehanna Avenue in North Philadelphia, was a major pretzel maker in the first half of the twentieth century. Under the direction of businessman L. J. Schumaker (1878–1948), it merged with several pretzel makers nationwide to form the American Pretzel Company, which by the late 1910s controlled about 80 percent of the U.S. pretzel business.

National and Multinational Bakers

In addition to local companies, Philadelphia was home to the production facilities of large national and multinational baking firms in the twentieth century. Bond Bread, a brand name of the General Baking Company conglomerate based in Rochester, New York, established several plants in Philadelphia early in the twentieth century, including operations in Lower Northeast, South, and West Philadelphia. Cookie and cracker maker National Biscuit Company (later Nabisco) opened a plant at Broad and Glenwood Streets in North Philadelphia in the early twentieth century, then moved in the 1950s to a large plant on Roosevelt Boulevard in the Far Northeast. After going through several ownership changes, the plant closed in 2015. By this time, much of the industry had consolidated and moved out of the area, leaving just one large-scale bakery in the city, the Tasty Baking Company.

Philip Baur (1885–1951), a baker from Pittsburgh, and Herbert Morris (1882–1960), an egg salesman from Boston, founded the Tasty Baking Company in Philadelphia in 1914 with the novel idea of selling individually wrapped, fresh-baked snack cakes. Their first bakery on Sedgley Avenue in Germantown was successful, and in 1922 Baur and Morris opened a large plant on Hunting Park Avenue in Nicetown. The company’s “Tastykake” products became longtime area favorites. In 2010 the Tasty Baking Company moved to a new modern production facility at the Philadelphia Naval Business Center in South Philadelphia, where it employed eight hundred workers. In 2011 Georgia-based food conglomerate Flowers Foods acquired Tastykake and began to distribute its products nationwide.

From modest beginnings in the late seventeenth century to the growth of large-scale baking operations in the twentieth century, the Philadelphia area has a long, rich history of bakers and bakeries. The region’s signature baked goods–Italian rolls, pretzels, and snack cakes–were still made locally in the early twenty-first century, while the area continued to support a wide range of baking operations from small family-run bakeries to large industrial bakers with regional and national distribution.

Jack McCarthy is an archivist and historian who specializes in three areas of Philadelphia history: music, business and industry, and Northeast Philadelphia. He regularly writes, lectures, and gives tours on these subjects. His book In the Cradle of Industry and Liberty: A History of Manufacturing in Philadelphia was published in 2016, and he curated the 2017–18 exhibit Risk & Reward: Entrepreneurship and the Making of Philadelphia for the Abraham Lincoln Foundation of the Union League of Philadelphia. He serves as consulting archivist for the Philadelphia Orchestra and Mann Music Center and directs a project for Jazz Bridge entitled Documenting & Interpreting the Philly Jazz Legacy, funded by the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University