Boarding and Lodging Houses

By Wendy Gamber

Essay

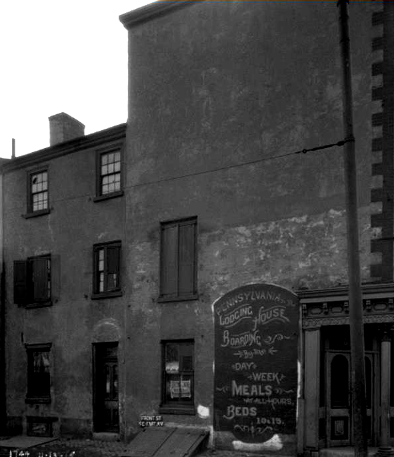

Distinguished by its ubiquitous row houses and high rates of home ownership, Philadelphia has been long been known as a “city of homes.” But for much of its history, it also has been a city of boardinghouses. “Boarding” and “lodging” houses did not enter the local lexicon until the late eighteenth century, but the practice of feeding and sheltering strangers was far older. These establishments, which proliferated in the nineteenth century, remained vital into the twenty-first century, as an alternative to the idealized single family home.

In eighteenth-century Philadelphia, master mechanics customarily boarded apprentices, who received food, lodging, and craft training in exchange for their labor. Farmers in the surrounding rural counties boarded hired hands. Families of all social ranks took in lodgers, accommodating unmarried men and women who had few other housing options. Taverns sheltered both travelers and long-term residents. By the 1780s, however, enterprising proprietors began advertising “genteel” boarding and lodging in the city’s newspapers, sometimes promoting their establishments as superior to taverns. The trend spread rapidly; Robinson’s Philadelphia Register and City Directory for 1799 included nearly one hundred boardinghouses.

By the late nineteenth century these numbers had increased tenfold. Indeed, by accommodating migrants from the surrounding countryside as well as immigrants from Ireland, Germany, Britain, and, later, Italy, Poland, and Russia, boardinghouses helped to make Philadelphia’s rapid economic and population growth possible. Nearby cities experienced similar boardinghouse booms. Wilmington directories listed seven boardinghouses in 1814, forty-three in 1874, and 174 in 1900; the number of boarding places in Camden rose from only eight in the early 1860s to 137 at the turn of the twentieth century.

How Boarding Shaped Urban Life

These statistics vastly underestimate the degree to which boarding shaped urban life. Historians estimate that one in four nineteenth-century Philadelphia households included boarders. These residences ranged from relatively large concerns that resembled small hotels to homes that sheltered a single lodger. Boardinghouses could be remarkably cosmopolitan, bringing together people who otherwise never would have met. More often they reinforced ethnic, racial, class, and occupational distinctions. Boardinghouses near Independence Hall housed middle-class clerks and merchants who worked nearby. Establishments that catered to the elite, such as the boardinghouse on Spruce Street run by Ann Smith, could be found in Society Hill. Working-class families who lived in the alleys off major downtown streets took in boarders; so, too, did the inhabitants of the heavily Irish neighborhoods of Southwark, Kensington, and Moyamensing. Immigrants from other ethnic groups settled into their own boarding places, usually run by a woman from the old country. Sailors’ and stevedores’ boardinghouses clustered near the Delaware River docks. Before the University of Pennsylvania opened its first dormitories in 1900, most of its students lived in the nearby “boarding house colony.” Not all boardinghouses were urban. In rural New Castle County, E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company paid its married workers to board bachelor employees.

Before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and in some cases after, public accommodations, even in northern cities, were segregated by race. African American boardinghouse keepers performed a vital function by accommodating people of color, both travelers and permanent residents. And before the Civil War, African American boardinghouses in Philadelphia and Camden occasionally functioned as informal stops on the Underground Railroad by sheltering fugitives from slavery.

If boardinghouses provided food and shelter to transients and newcomers, they also provided women with a means of making a living or supplementing their families’ incomes. In 1880 Margret McNamara (b. c.1840), the wife of a peddler, housed nine boarders, all of them Irish immigrants like herself, in her residence on Mifflin Street in South Philadelphia. McNamara did not describe herself as a boardinghouse keeper, perhaps because doing so might suggest her husband’s income was insufficient to support her. As her experience suggests, much boarding and lodging housekeeping in Greater Philadelphia, as elsewhere, consisted of what economists call hidden market labor. Even when census takers or city directories identified a man as the establishment’s proprietor, women undertook the considerable labor keeping boarders entailed—cooking, cleaning, monitoring comings and goings, collecting rents. When the DuPont Company paid male employees who agreed to house unmarried workers, they paid men for work their wives performed.

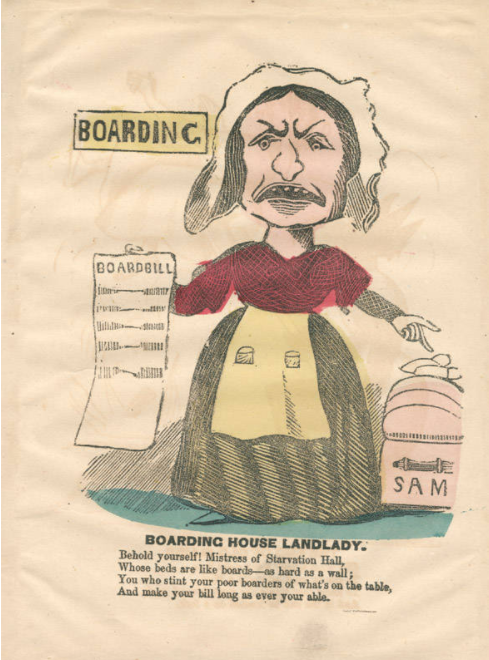

Boarding as the Butt of Jokes

Boarders did not always appreciate the fruits of these labors. Philadelphians, like their counterparts elsewhere, participated in a lively, often humorous, anti-boardinghouse discourse. An 1854 issue of the Philadelphia Mercury carried the surely apocryphal story of a boardinghouse keeper who saved money by serving soup made with kittens. Irish longshoremen who labored on Philadelphia’s docks in the early twentieth century recalled a landlady who smeared fat on the faces of sleeping inhabitants to deceive them into thinking they had been fed. In 1881 the Wilmington Morning News poked fun at the less than desirable accouterments, including smelly mattresses and dingy sheets, at a boardinghouse that advertised “meels & login cheep.” Even the social elite were not exempt from the unsavory conditions that supposedly afflicted boardinghouses. In the 1860s one resident of a fashionable Philadelphia establishment complained about an unwelcome nocturnal visitor—a “promenading” rat. Criticisms of this sort no doubt reflected the realities of boardinghouse life. Most landladies could not afford to lavish delicacies on their tenants, nor did they typically command a labor force capable of maintaining exacting standards of cleanliness. By the same token, most boarders could afford to pay only modest rents—more often than not they got what they paid for. But the sheer ubiquity of boardinghouse folklore also revealed a persistent cultural tendency to contrast the deficiencies of boardinghouses with idealized single-family homes.

By the turn of the twentieth century, these complaints had taken a more ominous turn. City officials and social reformers bemoaned the “lodger evil,” especially in Little Italy and the African American neighborhoods clustered along Lombard Street in Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward. While the authors of various housing studies recognized the importance of boarders and lodgers to working-class family economies, they feared the moral danger paying guests allegedly posed. W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963), for instance, condemned the “pernicious” influence of lodgers, whom he believed destroyed “the privacy and intimacy of home life.”

Early twentieth-century social reformers believed that lodging houses—more commonly called “furnished room houses”—presented a different kind of moral problem. While nineteenth-century commentators sometimes used “boarding” and “lodging” interchangeably, semantic distinctions became more important as lodging houses rapidly replaced boardinghouses in downtown Philadelphia, Camden, and Wilmington. Lodgers, also called roomers, took their meals at nearby restaurants instead of at a common table. Unlike boarders, they came and went as they pleased. The salesmen, clerks, stenographers, and secretaries who rented furnished rooms enjoyed the greater privacy and social freedom lodging—as opposed to boarding—offered them.

Reformers and social scientists, however, voiced increasing alarm about “the furnished room problem.” The problem was less acute in cities such as Camden, which boasted only a few dozen furnished-room houses, most of them located near the block that became Johnson Park. Philadelphia’s rooming houses numbered close to a thousand. Contemporary observers acknowledged the difficulties of pinpointing the precise boundaries of the city’s constantly changing furnished-room districts, which encompassed portions of Society Hill as well as Frankford, Richmond, and Kensington. They agreed that the most prominent lodging-house neighborhood lay just north of Center City, bordered roughly by Race Street, Girard Avenue, Broad, and Sixth Streets. Reformers lamented roomers’ easy proximity to the saloons, movie theaters, vaudeville shows, and peep shows clustered on Eighth Street; they claimed furnished-room districts attracted crime, vice, and prostitution. Lodging-house critics even succumbed to historical amnesia by extolling the virtues of “the old-fashioned boardinghouse,” which, they argued, had provided a homelike atmosphere and familial supervision.

Boardinghouse Era Fades

By the 1950s, if not earlier, white-collar workers had decamped for apartments and rooming houses had become synonymous with skid row. Many of the latter, known in official terminology as single room occupancies (SROs), fell victim to gentrification and urban renewal, processes that left former residents homeless. While some old-style establishments survived into the 1950s and 1960s, by midcentury boardinghouses more commonly sheltered the poor, the elderly, and the mentally ill, often under unsafe and unsanitary conditions.

Nevertheless, boardinghouses—albeit by other names—survived and even flourished in the twenty-first century. During the Great Recession more than a few homeowners stayed afloat by taking in boarders, as suggested by the title of a 2009 Philadelphia Inquirer article: “Rooms for Rent: In a Flashback to Earlier Times, Recession-Pinched Homeowners are Seeking Paying Guests to Share their Space.” And whether they realized it or not, those residents of Greater Philadelphia who embraced alternative living arrangements out of choice rather than necessity also invoked past practices. Collective ventures such as West Philadelphia’s Life Center houses, the Penn Haven Housing Co-op, and the Friends Housing Cooperative owed their origins at least in part to these earlier forms of multifamily housing.

Wendy Gamber is the Robert F. Byrnes Professor in History at Indiana University, Bloomington. She is the author of three books: The Female Economy: The Millinery and Dressmaking Trades, 1860-1930, The Boardinghouse in Nineteenth-Century America, and The Notorious Mrs. Clem: Murder and Money in the Gilded Age. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Wissahickon civic group addresses upswing in "boarding house" variance requests (WHYY, February 8, 2012)

- N.J. boarding home housing people with mental illness comes under scrutiny (WHYY, July 4, 2014)

- Atlantic City boarding house that outlasted two casinos goes to auction (WHYY, July 18, 2014)

- Advocates: N.J. measure would expose 'filthy conditions' in boarding homes (WHYY, September 26, 2014)