Brickmaking and Brickmakers

By Tamara Gaskell and Sarah K. Filik

Essay

The city of Philadelphia was built with bricks, giving it an appearance many neighborhoods retained into the twenty-first century. An abundance of local clay allowed brickmaking to flourish and bricks to become the one of the most important building materials in the region. Because it could be accomplished with just a few rudimentary tools, brickmaking was one of the first industries practiced in colonial America. For two centuries, Philadelphia was America’s preeminent brickmaking city. Though brickmaking declined as clay deposits were depleted and concrete blocks became more economical, locally made bricks, and local brickmakers, made possible the distinctive built environment of Philadelphia and the surrounding region.

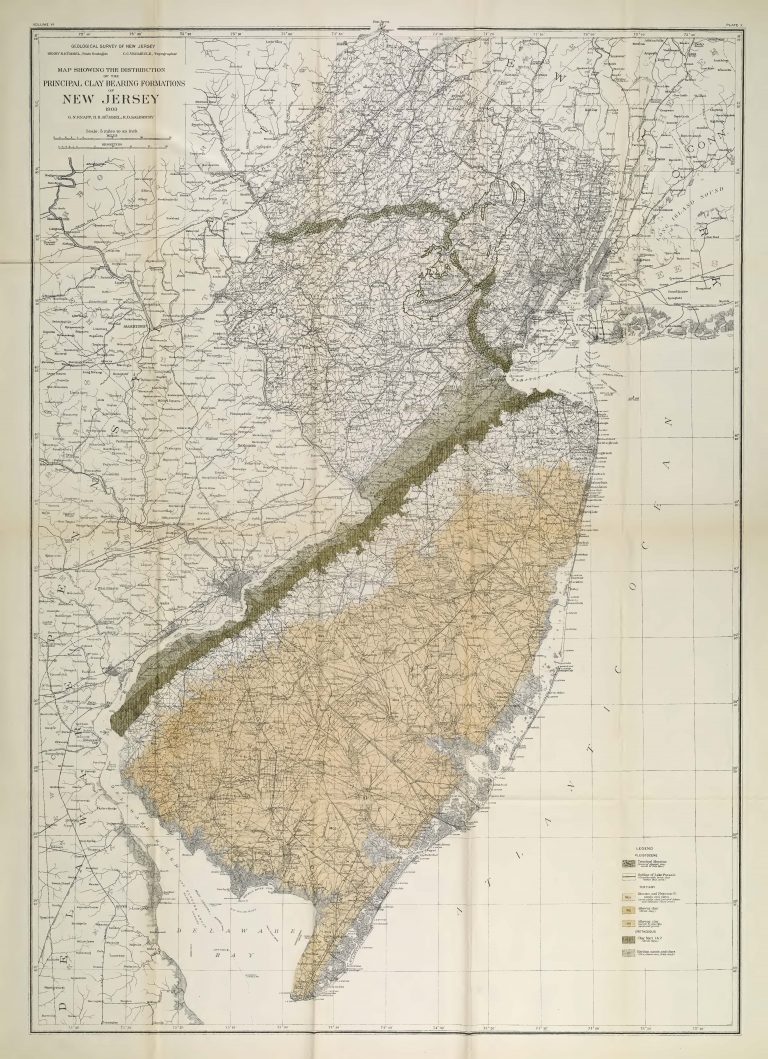

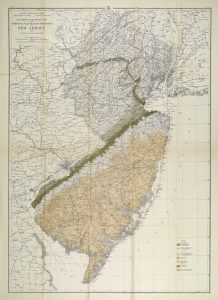

“Brickmaking was a poor man’s game, as it required no capital to start with,” noted New York brickmaker James Wood in 1830. This was especially true early on, when firing bricks required only enough bricks to build a kiln and, most importantly, an abundance of clay. Philadelphia sat atop a bed of high-quality brick clay just below the surface, so extensive that even after two centuries of mining it still provided enough clay to produce more than 200 million bricks a year by the end of the nineteenth century. The best quality brick clay was in the “Neck,” between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. New Jersey had wide-ranging deposits of clay running diagonally across much of the state. Arguably, the best quality was found in Middlesex County, however suitable clay could also be found across the southern portion, particularly along the Delaware River in Burlington County.

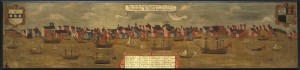

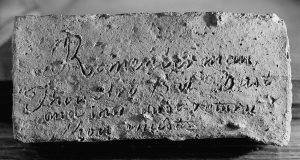

Archaeological remains, such as kilns, indicate that brickmaking began almost as soon as settlers arrived in the Philadelphia region. In the area that became Delaware, brickmaking occurred in New Castle, known then as New Amstel, at least as early as 1656 and supported construction of many of the city’s early buildings, such as the courthouse (1732) made with Flemish bond brickwork. Burlington County, New Jersey, with its rich clay deposits, had enough brickmakers by the early 1680s that it appointed two brick inspectors tasked with reporting any violations of a New Jersey law regarding the uniformity of handmade bricks. But the center of brickmaking was Philadelphia. In 1683, William Penn (1644–1718) described “divers brickeries going on.” Merchant Robert Turner (1635–1700), who built the first brick house in Philadelphia, reported to Penn in 1685, “Bricks are exceeding good, and better than when I built: More Makers fallen in, and Bricks cheaper. . . . many brave Brick Houses are going up.” Francis Daniel Pastorius (1651–c. 1720), the founder of Germantown, reported a number of brick kilns in the area in 1684, and Turner noted that Pastorius himself intended to begin brickmaking the following year. Brick was also used for public buildings: the courthouse at Second and High Streets, also known as the Guild Hall or the Great Towne House, begun in 1707, became one of the oldest public buildings in the colonies built of brick, and the Pennsylvania State House, one of the city’s most widely recognized structures, was constructed with locally made brick beginning in 1732. By the end of the eighteenth century, 80 percent of Philadelphia’s houses were made of brick. Early Philadelphia brickmakers demonstrated pride in their trade. On July 4, 1788, they marched in the Grand Federal Procession celebrating the ratification of the Constitution wearing aprons and carrying trowels and a green flag featuring a kiln.

A Family Business

Brickmaking was frequently a family business, spanning generations. Mechanics who worked in the trade became brickyard owners, often in partnership with family members. Intermarriage between brickmaking families cemented business ties. Among Philadelphia’s most prominent early brickmakers were brothers-in-law Daniel Pegg (c. 1660–1702) and Thomas Smith (?–c. 1690) and their relatives, the Coats family and William Rakestraw Jr. (c. 1678–1732). Peter Grim, who was in business by 1814 and who later, in the early 1830s, established a brickyard in Trenton and supplied the bricks for the New Jersey state prison, had many relatives in the business by midcentury. George, Michael, and Christian Lybrant all ran brickyards between 1800 and 1850. Nelson Wanamaker (c. 1812–62), father of department store pioneer John Wanamaker (1838–1922), worked with his father, John S. Wanamaker, in his brickyard in the Neck before John senior moved to Indiana in 1849. Family businesses continued their dominance until at least the mid-nineteenth century.

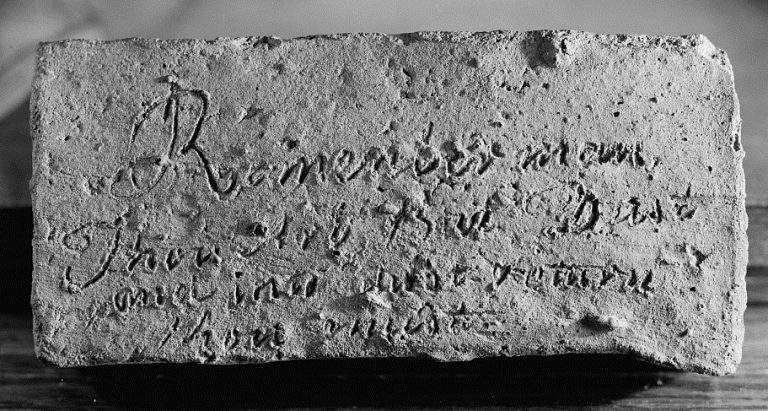

The process of making bricks changed little from its origins through the mid-nineteenth century. Brickmakers dug the clay, allowed it to weather, tempered it, molded it, let it dry, then burned the bricks in a kiln. Brickmaking began in early winter with the digging of clay, which was left exposed to the weather until the spring, allowing frost and rain to wash away salts and break up the clay. In the spring, brickmakers tempered the clay, mixing it with sand and water to get the right consistency and color and churning it in a “ring pit” with a horse- or oxen-drawn shaft. After the clay was tempered, a “wheeler” hauled it to the molder, the most experienced member of the brickmaking crew, who filled the wooden brick molds and removed excess clay. The “offbearer,” often a boy, then transported the filled molds to a drying yard and emptied the molds, leaving the bricks to dry in the open for a few days before stacking them in an open-sided shed for further drying. Once ready for burning, brickmakers stacked the bricks in a kiln, where they were “burned” over several days. They then sorted the bricks by firmness and color. Brickyards in the region typically produced about 2,400 bricks per day per crew (one molder and two offbearers).

The most significant costs of brick manufacture were for labor and fuel. Labor accounted for about 60 percent of production costs. Fuel, in the form of cordwood, accounted for another 30 percent. Each kiln burn required about twenty-five cords of wood, the fuel of choice into the late nineteenth century, even as area forests disappeared. By 1850, Philadelphia brickyards consumed about 38,000 cords of wood, or the equivalent of 1,360 acres of forest, a year.

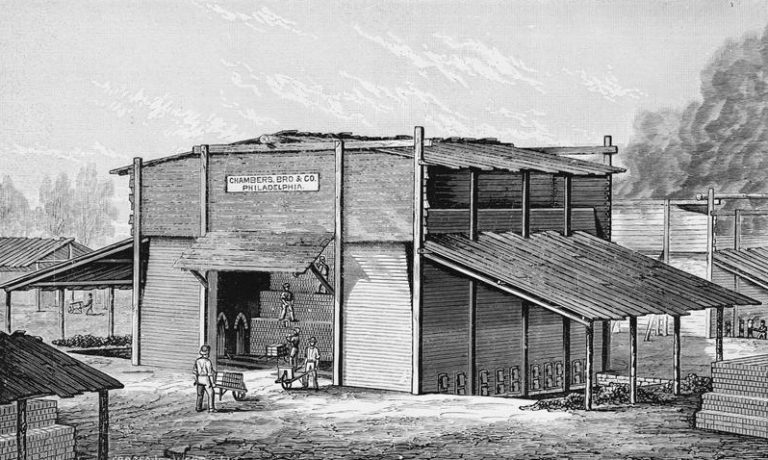

Rapid Expansion

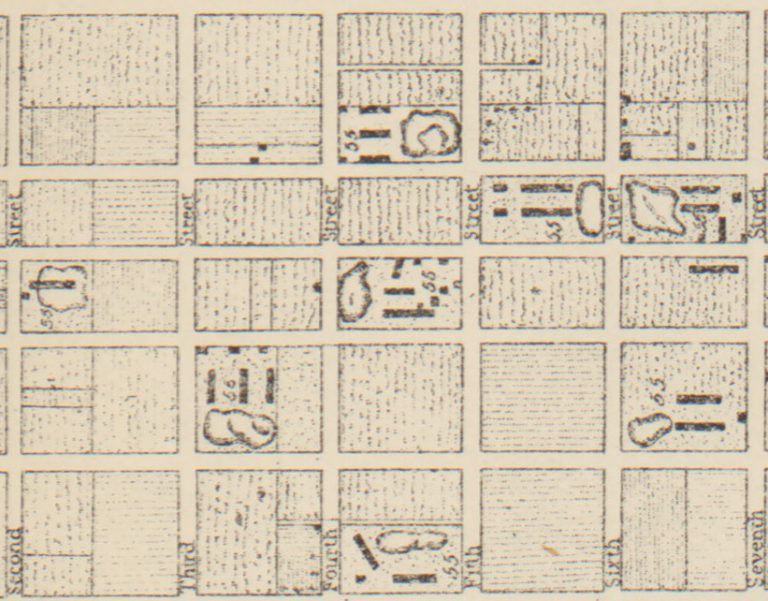

Brickmaking expanded rapidly in the region. In Wilmington, a 1791 list of area manufacturers included several bricklayers and brickmakers. By 1794 the Plan of the City and Suburbs of Philadelphia recorded fourteen brick kilns within city boundaries. Several of the earliest kilns were established in Germantown and Northern Liberties, with the latter the center of the early industry in the area. By 1799 brickmaking employed enough people that workers founded the Bricklayers Company, which persisted well into the twentieth century. In 1811, there were thirty brick kilns in Philadelphia, and by 1857, the city had at least fifty brickyards. A number of yards had also been established in and around Trenton and elsewhere in New Jersey by this time. By 1875, the number of brickmaking companies in Philadelphia peaked at about seventy-eight, and by the final decades of the nineteenth century there were many others in the surrounding region, including in West Chester, Norristown, Landsdowne, Bordentown, Maple Shade, Millville, Camden, Wilmington, and elsewhere.

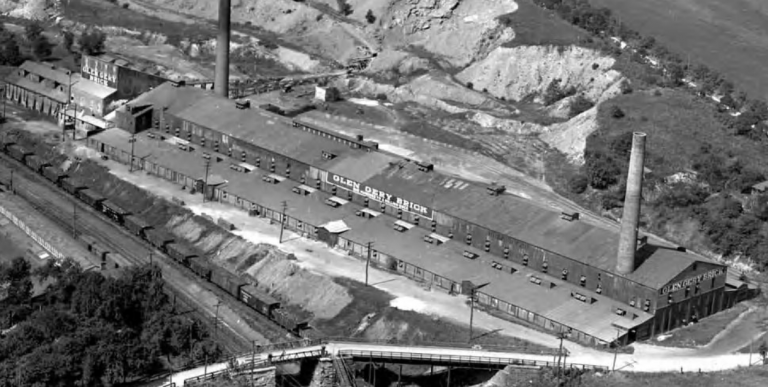

These brickyards employed a significant number of the region’s laborers. In 1810, at least six hundred men and boys were engaged in the brickmaking business in Philadelphia alone; by 1850, nearly two thousand worked in the industry. In that year, many yards employed about twenty-five men and boys, and six yards employed more than fifty workers each. The numbers continued to grow, so that by 1880 nearly three thousand men worked in the trade before the numbers started to decline at the end of the century. Though the exact numbers of laborers involved in the many smaller brickyards in the rest of the region are not known, the output of bricks suggests that growing numbers of men in southeastern Pennsylvania and in southern New Jersey also entered the brickmaking trade. In the early twentieth century, the Sayre & Fisher Brick Company in Middlesex County, New Jersey, founded in 1850 by James Sayre (1813–1908) of Newark and Peter Fisher (1818–1906) of New York, became the world’s largest brick manufacturer for a period. Sayre & Fisher employed hundreds of workers, especially new immigrants, who made up the bulk of the population of the town, soon renamed Sayreville. Much company housing, some built from the company’s bricks, survived into the twenty-first century. By its one hundredth anniversary, Sayre & Fisher had produced over six billion bricks. The plant operated until 1970. Brickmaking never became very significant in Delaware, however.

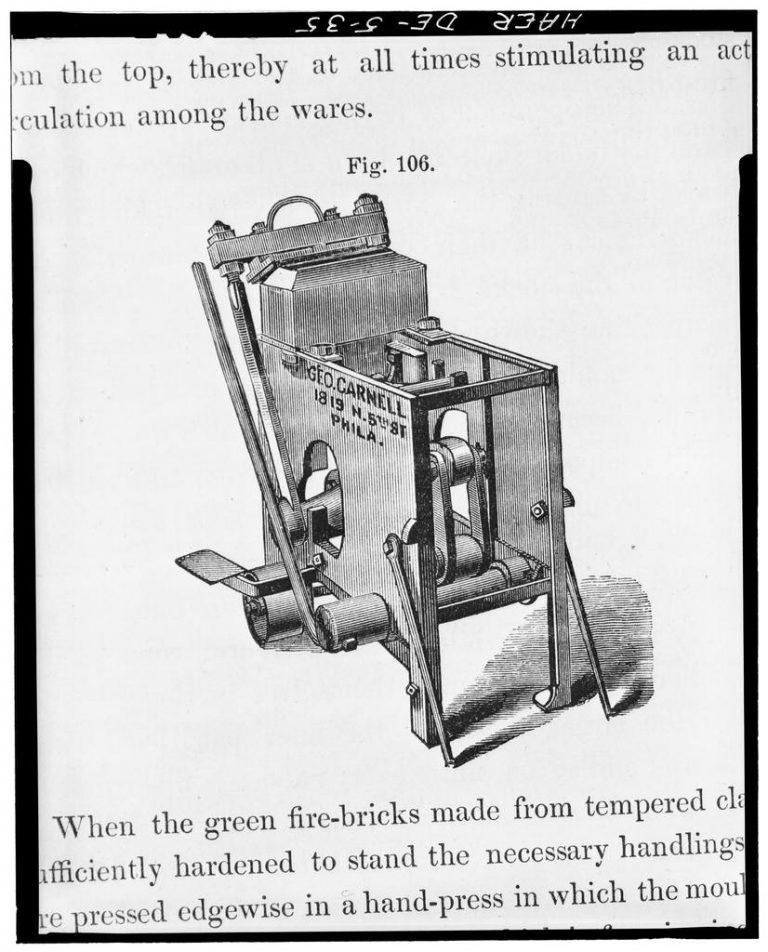

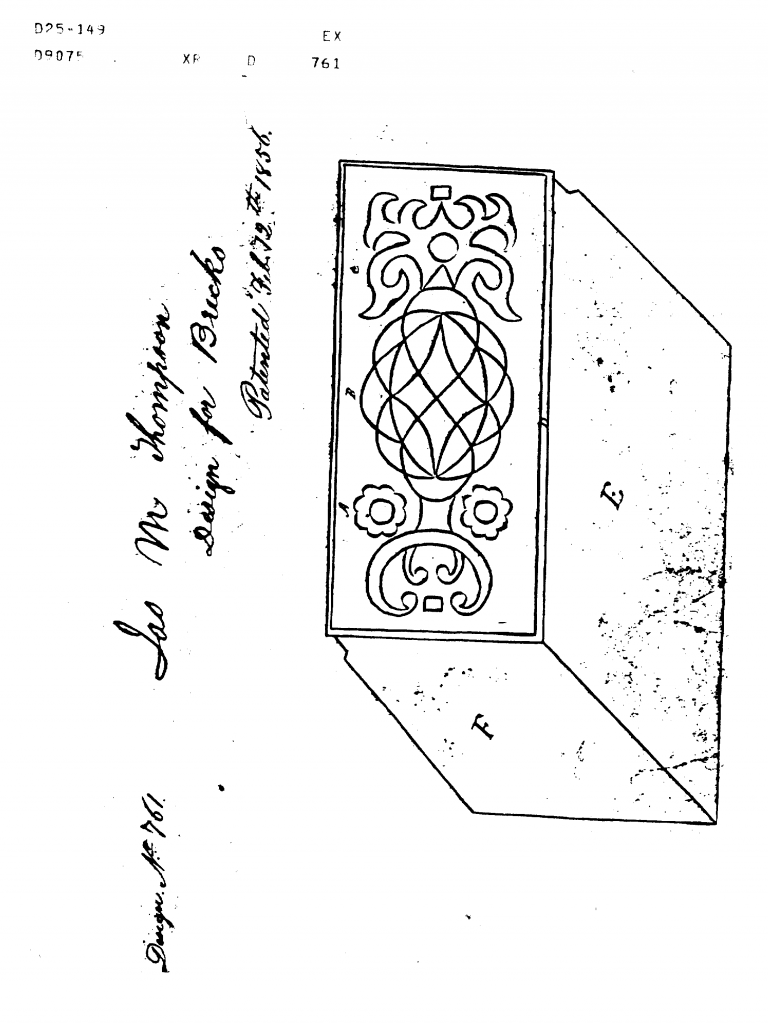

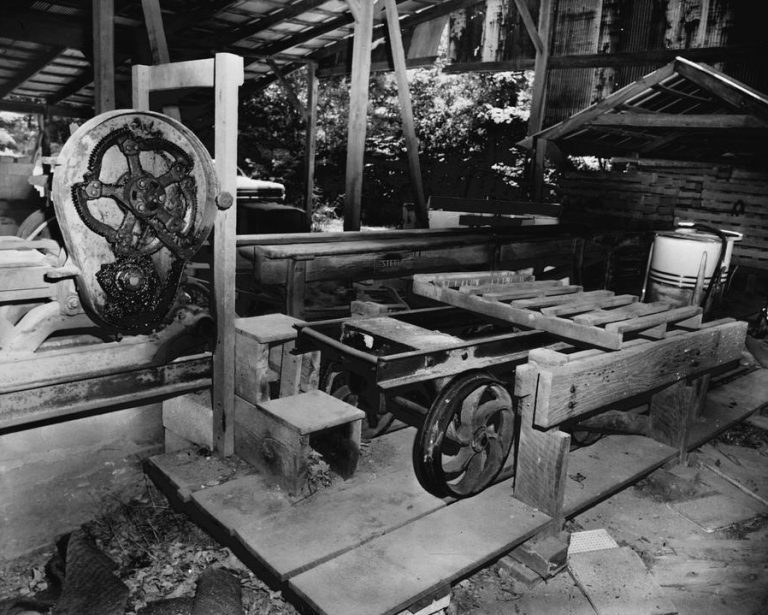

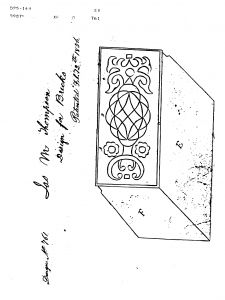

During the nineteenth century, the invention of new steam-powered machinery transformed brick production in many regions of the country, but Philadelphia brickmakers were slow to adopt these innovations. All brick had been made by hand until the mid-1830s, when Nathaniel Adams (1797–1862), who came to Philadelphia from the brickmaking region in the Hudson Valley, invented a molding machine; by about 1840 he installed a horse-powered machine in a Philadelphia brickyard. However, workers angry at the prospect of losing pay to a machine destroyed his machinery. A few years later, his brother, Samuel, installed one of his brother’s machines and then was forced to flee the city. Most Philadelphia brickmakers continued to hand mold bricks through the end of the century. The most popular innovation among Philadelphia-area brickmakers was the brick press. Samuel Fox (1777–1870) had one in his yard in 1838, a simple machine that allowed hand-molded brick to be pressed a second time to make a denser and more uniform block. By 1850, several local yards reported having presses, and Philadelphia became the leading producer of pressed bricks, commonly used for front façades and decorative purposes.

At the close of the nineteenth century, Philadelphia was producing about 220 million bricks annually. High demand for housing along with the high shipping costs for heavy material meant that it was much more economical to use locally made bricks. In 1903, Pennsylvania, led by Philadelphia, ranked second in the nation as a producer of clay products (behind Ohio), but it ranked first in the manufacture of common bricks and pressed bricks. New Jersey was not far behind, ranking fifth. Delaware, on the other hand, did not have a significant brickmaking industry.

Brickmaking declined in the twentieth century, however, and disappeared from the region by the twenty-first century. The turn of the twentieth century brought competition in the form of concrete and other building materials and new architectural styles. Concrete blocks—one eight-inch-wide concrete block could take the place of twelve bricks—began to displace bricks in foundation walls and as backup for wall facings. Brick usage decreased dramatically after the 1920s. In some areas, clay deposits had been depleted. By the mid-twentieth century, most brick manufacturers in the region had ceased operations. By the twenty-first century the region had many wholesalers that supplied brick and other masonry for construction, but it no longer was home to any active manufacturers, who operated primarily in the South and South Central United States.

Philadelphia’s built environment, however, continued to proclaim the city’s proud history as the nation’s leading brickmaking city into the twenty-first century. Without its many distinctive brick buildings, Philadelphia would lose much of the character its residents and visitors have come to enjoy.

Sarah K. Filik is a graduate of Rutgers College and obtained an M.A. in Art History from the University of Delaware. She has been a board member of the Sayreville (N.J.) Historical Society for several years. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Tamara Gaskell is Public Historian in Residence at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities and co-editor of The Public Historian. Previously, she was editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography and Pennsylvania Legacies, while director of publications at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and an assistant editor of the Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University