Eugenics

Essay

In 1883 Francis Galton (1822–1911), an English statistician and sociologist, invented a term for his decades-long genealogical investigations into “fit” and “unfit” families: eugenics, the scientific study of being well-born. While Galton tended to focus on the fit, in the United States, enthusiasts for eugenics more often focused on those deemed biologically unfit. Elwyn, Pennsylvania, and Vineland, New Jersey, housed two key institutional centers and many individuals responsible for studying the supposed biological basis for social deviancy and dependency. They and their political and professional allies used those dubious findings to promote a sweeping agenda of eugenic policies, including sterilizations. Vineland, in particular, became one of the most important centers for eugenic research and propaganda in America, while Elwyn witnessed some of the first sterilizations to be performed in an institution.

Interest in studying and perhaps channeling human heredity long predated eugenics. Philadelphia in particular, with its extensive network of academic, medical, scientific, and philanthropic institutions, helped develop some of the key early institutions that applied quasi-scientific theories of fitness to issues of social welfare. The Philadelphia Society for Organizing Charity (SOC), established in 1878, one of the first of about two hundred similar organizations nationwide, exemplified the new “scientific” approach to treating dependent persons based on their perceived moral and biological worthiness, or lack thereof. These charity organizers, many of whom eventually moved into eugenics, argued that the chronically poor, the insane, alcoholics, some criminals, the “feeble-minded,” and prostitutes represented a single, biologically distinct substratum of humanity that passed on its defects from generation to generation. Leaders claimed that by identifying such individuals and promoting cooperation between charities, they could prevent such persons from sustaining themselves by going from one charity to the next. This in turn would motivate those who could work to find gainful employment, end the need for taxpayer-funded relief, and cause the truly degenerate to wither and die, unable to pass on their defective taint.

Based on such logic, within a year of the SOC’s founding, Philadelphia eliminated all public funds given to support the poor outside of institutions. In doing so, the city was at the forefront of a nationwide trend in reducing or eliminating public relief. Efforts to bring greater efficiency and scientific scrutiny to poor relief in the greater Philadelphia area echoed associated work to reform charitable and correctional institutions. Pennsylvania had long boasted of its leading role in providing humane institutional care, but by the 1880s institutions nationwide were besieged by critics who simultaneously argued that they were too great a drain on public funds, yet also provided inadequate and inhumane services based on outdated principles. The insane asylum in Philadelphia, for instance, was kept within the larger confines of the Blockley Almshouse on Thirty-Fourth Street. When a fire swept through on February 12, 1885, more than twenty inmates, locked into their rooms from the outside and many physically restrained, died.

“Race Suicide”

Complaints about wasteful spending on inhumane social welfare programs, coupled with alarm over “race suicide”—a theory that held lower-class, biologically suspect whites were out-reproducing the white upper class, which, along with immigration and births in African American families, would result in the swamping of the better heredity of the white professional class—gave rise to the nationwide eugenic agenda to identify, isolate, and even sterilize certain classes of dependent persons. This effort was in large part built on the work of Drs. Isaac Kerlin (1834–93) and Martin Barr (1860–1938) at the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble-Minded Children in Elwyn, in Delaware County, and Henry Goddard (1866–1957) at the Vineland Training School in New Jersey. Under their direction, these institutions became two of the most important centers for eugenic research and pro-sterilization arguments in America. Kerlin, the superintendent at Elwyn from 1864 to 1893, was one of the nation’s foremost experts on the education and institutional care of children with intellectual disability. In his 1892 presidential address to the Association of Medical Officers of American Institutions for Idiotic and Feeble-Minded Persons—an organization he founded—he acknowledged an “asexualization” surgery performed at his institution, and he became one of if not the first to recommend the practice. Records are spotty, but historians generally believe that Kerlin’s also were the first sterilizations performed in an American institution.

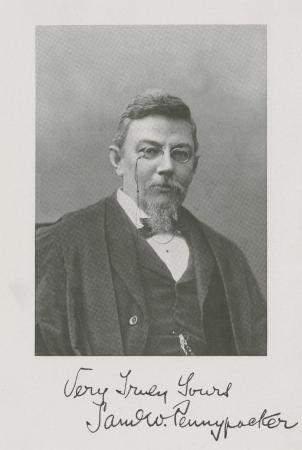

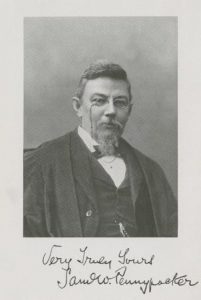

His protégé and subsequent superintendent at Elwyn, Martin Barr, led the Philadelphia area’s lobbying effort for a state law authorizing sterilizations. The 1901 “Bill for the Prevention of Idiocy” would have given legal sanction to the castrations he already was performing. It passed both houses before a “technicality” in language led Governor William Stone (1846–1920) to conclude it had not passed properly and return it to the legislature, where it died. A sterilization law passed in 1905 would have been the first in the nation had not Governor Samuel Pennypacker (1843–1916) vetoed it with a rousing statement in defense of the rights of institutionalized persons. Several more bills failed to get through the legislature in subsequent years. All the while, Barr continued sterilizing residents of the Pennsylvania Training School and pivoted from arguments about the procedure’s educational and therapeutic value to more extravagant claims that it might eliminate the supposed hereditary source of many cases of intellectual disability. From Kerlin’s first sterilization through 1931, the school oversaw about 270 sterilizations. It is unclear how many of those involved consent from the individuals or their guardians; notions that vulnerable people might have a right to informed consent before submitting to medical procedures did not become prominent in America medical ethics until the 1950s and 1960s. While the Supreme Court had ruled in favor of the legality of involuntary sterilization in the notorious Buck v. Bell case in 1927, Pennsylvania had passed no law ruling on its permissibility within the state. Indeed, at no point did Pennsylvania actually enact a law permitting sterilizations of persons in institutions, though thirty-three other states did. Still, superintendents at Elwyn persisted. The superintendent who succeeded Barr, Dr. E. Arthur Whitney (1895–1966), proposed such legislation at every legislative session from 1929 to 1951.

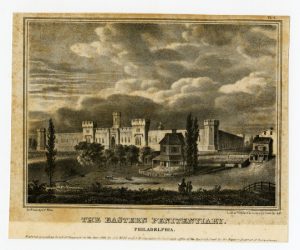

Though the Pennsylvania Training School led the effort to pair medical and scientific expertise with state authority to restrict reproductive rights, it had many allies. The administration at Eastern State Penitentiary similarly turned to eugenic arguments to explain the underlying causes of crime. Like the training school, Eastern State had been founded on the progressive premise that its charges could be reformed and improved, but according to a 1907 report of the inspectors, favored “restricting the liberty and power of degenerates to transmit their criminal propensities to unfortunate progeny” as the only solution.

The explosive growth in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries of institutions for people with intellectual disabilities, including the facilities in Polk and Pennhurst, Pennsylvania, also expressed the eugenic aspiration of restricting the right to reproduce among the “unfit.” So too did efforts nationwide to require medical examinations determining couples’ fitness to marry or prohibiting marriage for persons with certain classifications of mental illness or intellectual disability, including New Jersey’s 1904 marriage law, and the judicial reform movement to allow for indeterminate sentencing of criminals. In such efforts, eugenic reformers in the greater Philadelphia area and nationwide resembled and often overlapped with the public health movement, which similarly used the threat of illness and promise of scientific cures—most notably, the discovery by Robert Koch (1843–1910) that tuberculosis was contagious—to argue for coercive measures to advance the nation’s health.

Henry Goddard

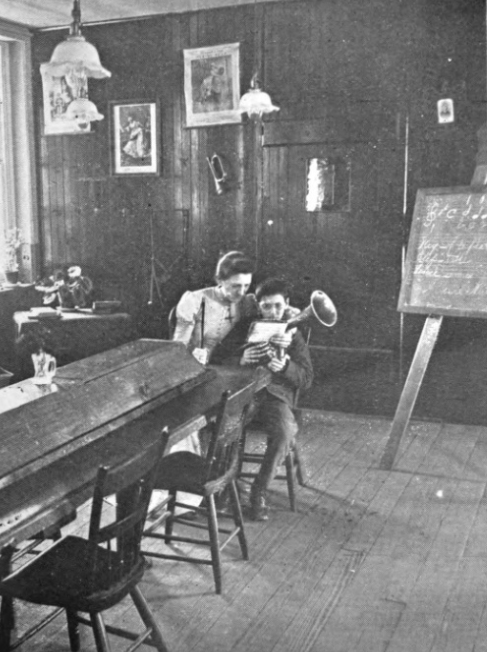

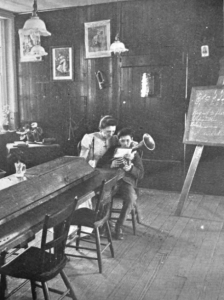

The eugenicists’ work culminated in Henry Goddard’s work for the Vineland Training School for Feeble-Minded Boys and Girls. After completing his doctorate of psychology at Clark University in 1899, Goddard taught pedagogical courses for the West Chester State Normal School. He did so at a moment when Pennsylvania and New Jersey struggled to meet the challenge of educating children with intellectual disability in their rapidly expanding public school systems. His interest in this challenge resulted in an opportunity for him to serve as the first director for research at Vineland, a position he accepted in 1906. Vineland’s superintendent envisioned the new research department to function as a psychological laboratory for investigating good teaching practice in the field later known as special education. Goddard, however, soon came to share the pessimism of physicians like Barr, with whom he collaborated. His research produced two crucial works justifying sterilizations of persons with intellectual disability. First, Goddard’s assistant, Elizabeth Kite (1864–1954), a Philadelphian, translated the works on childhood intelligence of French psychologist Alfred Binet, (1857–1911), and from this Goddard created some of the first intelligence tests. He used these to classify the children at Vineland based on their intelligence and capacity to improve from education, and from there, such testing soon swept the nation.

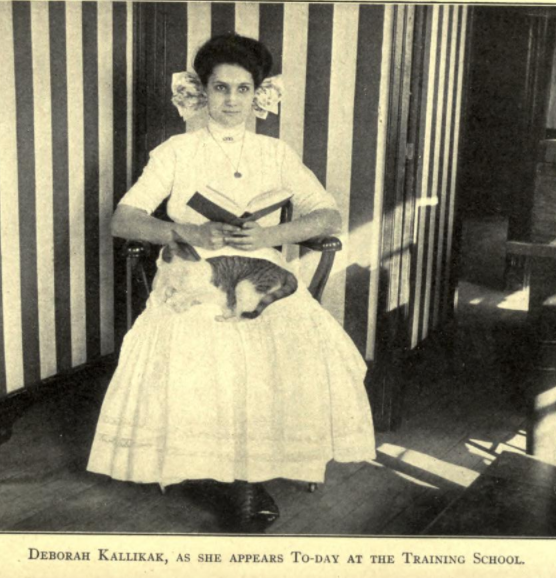

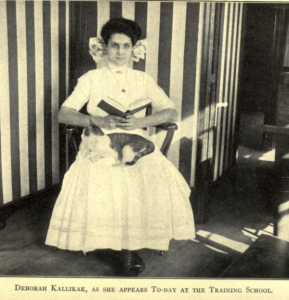

Armed with these tests and a new scheme for classifying levels of intellectual disability, Goddard’s staff of field workers—mostly college-educated women whose work was supported by Philadelphia philanthropist Samuel Fels (1860–1950)—sought to identify families with long histories of intellectual disability and immoral living. Their work resulted in the 1912 publication of The Kallikak Family. In it, Goddard traced a legacy of criminality, sexual wantonness, feeble-mindedness, and poverty across six generations, arguing that their causes were hereditary, not environmental. It is a work whose lack of rigor and amount of outright fabrication were exceeded only by its enthusiastic reception in its time. The Kallikak Family became an international phenomenon and made Goddard one of the figures most closely associated with American eugenics. Vineland’s Committee on Provision for the Feeble-Minded functioned as a national campaign office and soon relocated to Philadelphia, where it produced public pro-eugenic exhibits that attracted one hundred thousand visitors. Goddard also brought his tests to Ellis Island, where the dismal—and very flawed—results quickly became fodder for anti-immigration activists. Ironically, New Jersey had passed a sterilization law the year before publication of The Kallikak Family and the state supreme court overturned it the year after, with no sterilizations having occurred. Delaware, by contrast, had legalized sterilizations in 1923, without granting a right to counsel for those to be sterilized, most done at the Delaware State Hospital at Farnhurst.

Delaware frequently led the nation in involuntary sterilizations per capita in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, but several trends brought about a slow unwinding of eugenic policies nationwide. Diminishing fears of “race suicide” and revulsion at Nazi Germany’s sterilization program, which had been modeled on the legislative proposals of American eugenicist Harry Laughlin (1880–1943), a better understanding of the interplay of heredity and environment, changing medical ethics standards for informed consent, and disability rights activism all helped curtail the eugenics movement.

Yet echoes of such attitudes endured. Perhaps most infamous among regional examples, a 1990 editorial in the Philadelphia Inquirer became a source of nationwide controversy when it suggested offering incentives to mothers who received welfare if they used the long-term contraceptive Norplant. Though the paper insisted it did not mean to suggest eugenics and its concern for making birth control affordable and easily available to all women presaged more recent political debates, the editorial’s suggestion that birth control could solve generational poverty among the “underclass” reminded many critics of the simplified explanations and solutions for dependence characteristic of the eugenicists, as well as its racist baggage.

Brent Ruswick is an Assistant Professor of History at West Chester University of Pennsylvania. His historical research—including the monograph Almost Worthy: The Poor, Paupers, and the Science of Charity in America, 1877–1917 (2012)—concentrates on how professional communities defined and treated social deviancy in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. He also publishes and teaches in social studies education. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Mental Defectives: Their History, Treatment, and Training (Archive.org)

- “The Imbecile and Epileptic versus the Taxpayer and the Community.” (Google Books)

- The Kallikak family : a study in the heredity of feeble-mindedness (Archive.org)

- Manual of Elwyn (HathiTrust)

- National Conference on Social Welfare Proceedings (1874–1982)