Gardens (Public)

By Anastasia Day and Emily T. Cooperman

Essay

More than three centuries of private and public efforts have given the Philadelphia area the highest concentration of public gardens in the United States. Although William Penn (1644-1718) originally envisioned five squares dotting his metropolis, the energies of private citizens initially cultivated the plants, gardens, and landscapes of Philadelphia. From these beginnings, public gardens became larger, more numerous, and varied, establishing the region as a place of importance in American horticultural history.

The notion of a designed, urban public garden did not exist when Penn founded Philadelphia in the seventeenth century. His vision for a “greene country towne” held no provision for public parks or gardens. Instead, this characterization referred to the private use of land within the original city. Penn envisioned a system of large lots of a minimum of half an acre, with the house placed “in the middle of its platt, . . . so there may be ground on each side for Gardens or Orchards, or fields.” In this way, he sought to make his town green.

Penn set aside public land in the form of Philadelphia’s five squares, but, with the exception of the Central Square, they were not to be used as gardens but rather “as the Moor-fields in London.” While “walks” traversed them, London’s Moorfields primarily served as a multipurpose landscape where, for example, plague victims were buried and rival guilds met in battle. Similar uses predominated in Philadelphia’s squares before they became sites of city gardens beginning in the late eighteenth century. Militia drilled there; the squares later named Washington and Franklin held burial grounds; and Washington Square hosted a livestock auction. Clay was mined from the square later named Rittenhouse, and the square later named Logan was the site of public executions. Trash was dumped in them all.

Gardens of the Wealthy

A number of wealthy Philadelphians did create gardens in their large city lots, as well as at their country estates outside the original city limits, and many Philadelphians visited these gardens in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. John Bartram (1699-1777) and his son William Bartram (1739-1823), two of the continent’s most prominent botanists, were the first of a series of Philadelphia plantsmen to create demonstration gardens and nurseries. The first early gardens fully accessible to the (paying) public in the city, however, were associated with entertainment and refreshment rather than science and education. These included the “Cherry Garden” in the area that later became known as Society Hill and “Spring Garden,” which was accessed by boat up Pegg’s Run (roughly at Callowhill Street). John Fanning Watson (1779-1860) recorded that the early “Cheese-cake-house” garden, on the west side of Fourth Street north of Arch, featured fruit trees, “arbours and summer-houses.”

One of the best known of these early public gardens was at Gray’s Inn on the west side of the Schuylkill River near the point later crossed by Gray’s Ferry Avenue. Visitors to Gray’s Gardens, located on the main route south out of the city, wrote rapturously of their experiences there before and during the period of the American Revolution. They enjoyed musical entertainment and food and toured the extensive greenhouse, a series of summerhouses and other garden structures, and meandering walks. In the early nineteenth century, merchant Henry Pratt’s (1761-1838) Lemon Hill estate northwest of Philadelphia overlooking the Schuylkill River likewise opened its doors to the ticketed public. After Pratt’s death, the estate hosted public Sangerfests (German celebrations) until bought by the city in 1855 for Fairmount Park.

The development of the first truly public garden within the city began in 1784, when Englishman Samuel Vaughan (1720-1802) began a campaign to transform the State House Yard (later Independence Square). A close associate of Benjamin Franklin, Vaughan was an enthusiastic supporter of the young republic and its new cultural institutions and organizations, particularly the American Philosophical Society. It is no accident that the creation of the permanent home for the Philosophical Society in the State House Yard coincided with Vaughan’s work to make a garden there. One of Vaughan’s goals was to plant a collection of American trees, an ambition echoed in other early gardens. In a landscape featuring serpentine gravel walks and artificial mounds, with Windsor chairs and benches provided for visitors, the State House Garden’s plantings included one hundred American elms. The site became a political emblem of the advancement of the young American civilization.

The State House Garden

The State House Garden set an important precedent for reviving Penn’s original squares as the city’s development moved west from the Delaware River in the pre-Civil War period. A public garden in Center Square surrounded Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s pumping house for the short-lived Chestnut Street Waterworks. Southeast (later Washington) Square followed in the 1810s and became the centerpiece of an elite neighborhood, much as Southwest (Rittenhouse) Square did after mid-century. The garden in Franklin Square, established in the 1830s, featured a fountain supplied by the new Fairmount Water Works; the contemporary press marveled at the technological ingenuity of it. Many of these reinventions of Penn’s squares were the product of efforts from the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, founded in 1827. In 1829, the society hosted the first Philadelphia Flower Show in Masonic Hall on Chestnut Street, where twenty-five of Philadelphia’s elite gardeners showed their finest specimens.

The horticultural transformation of Fairmount Park in anticipation of the 1876 Centennial celebration of American independence ushered in a new generation of public landscapes. The Garden of the Zoological Society of Philadelphia opened to the public on July 1, 1874. Although it became known simply as the Philadelphia Zoo, it was originally conceptualized as a botanic garden hosting a zoological collection. Two years later, the Centennial Exhibition also promoted Philadelphia’s gardening skills. More than 20,000 trees, shrubs, and decorative hedges were planted over the exhibition’s 285 acres in Fairmount Park. The Colonial Revival that the Centennial helped to popularize led to a return to orthogonal geometry in “formal” gardens, not only in Fairmont Park of Philadelphia, but across the nation.

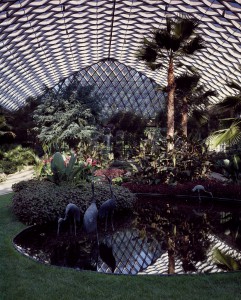

Horticultural Hall, a huge glass and iron structure and one of the two permanent buildings constructed for the Centennial, housed exotic and rare botanical specimens from around the world as well as indigenous American plants. It continued to serve as a conservatory until Hurricane Hazel ravaged it in 1954; the city razed the building the following year. For the 1976 Bicentennial, the city built a new Fairmount Park Horticulture Center on the site, complete with indoor greenhouses and outdoor perennial, annual, vegetable, and demonstration gardens.

First Large-Scale Japanese Gardens

Another legacy of the Centennial was one of the first large-scale Japanese gardens in the United States, a teahouse and garden exhibit created by the Japanese government in West Fairmount Park. After the Centennial, these features remained, later joined by the Nio-mon Temple Gate, which was moved from the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. After the gate burned down in 1955, it was replaced three years later by Pine Breeze Villa, or Shofuso, a gift from Japan to the United States. From its roots at the Centennial, this garden influenced American taste. It helped start a vogue for Japanese gardens in landed American estates and inspired appreciation for foreign gardening styles.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Philadelphians revived or invented gardens as numerous colonial-era estates became public historic sites. In 1888, the City of Philadelphia purchased Bartram’s Garden, which had remained in private hands till that time. The garden, the oldest surviving botanic garden in the United States, still holds a number of historic trees planted by the Bartrams, including the oldest ginkgo tree in the nation. Other historic estate gardens became public under the auspices of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. For example, in 1957 the state acquired the Highlands Mansion and Gardens in Fort Washington, a late eighteenth-century Georgian mansion with two acres of grounds.

The trend of turning estate gardens into public sites continued throughout the Philadelphia region over the twentieth century. In Philadelphia, the University of Pennsylvania purchased the Morris family’s Compton Estate in Chestnut Hill and then reopened it as the Morris Arboretum. In southeastern Pennsylvania and Delaware, a group of DuPont family estates also opened for visitors, notably Longwood Gardens in Chester County, which opened to the public after the death of Pierre S. DuPont (1870-1954), and sixty acres of naturalistic gardens at the nearby Winterthur Museum in Delaware. Other historic DuPont estates nearby include the Mt. Cuba Center, a preserve of the indigenous flora of the Appalachian piedmont; Nemours Mansion & Gardens, famed for its formal French gardens; and the Hagley Museum and Library, with original mansion gardens along the Brandywine River.

In May 2013, the American Public Gardens Association recognized the City of Philadelphia as “America’s Garden Capital” for National Public Gardens Day. Indeed, by the early twenty-first century Philadelphia had the highest concentration of public gardens of any area in the United States, with thirty public gardens within a thirty-mile radius. While part of this abundance sprang from Philadelphia’s original city plan, the number of private mansions turned to public gardens showed that the region’s interest in gardening extended beyond the limits of William Penn’s “greene country towne.”

Anastasia Day is a doctoral student and Hagley Fellow in the History Department of the University of Delaware. She studies environment, technology, and food, primarily in the American twentieth century. Her dissertation is on Victory Gardens in World War II. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Emily T. Cooperman is an architectural and landscape historian and historic preservation consultant. She serves as the principal of ARCH Preservation Consulting and as a senior consultant for Preservation Design Partnership. Her published work includes, with Lea Carson Sherk, William Birch: Picturing the American Scene (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- From comfort station to exhibit space in Fairmount Park (WHYY, March 23, 2013)

- Philadelphia's Franklin Square celebrates 7 years since revitalization (WHYY, July 31, 2013)

- Philadelphia Zoo nets $6M grant from William Penn Foundation (WHYY, September 16, 2013)

- Longwood Gardens doubles size of Meadow Garden (WHYY, June 9, 2014)

- Morris Arboretum birdhouses strictly for the people (WHYY, July 6, 2014)

- Conceptual designs for a lush LOVE Park (WHYY, March 25, 2015)

- Fairmount Park plans for the future (WHYY, May 4, 2015)

- A garden, a redevelopment plan, and a fight over who owns a neighborhood (WHYY, May 24, 2016)

- Reviving historic flower garden to help cultivate Philadelphia's connection with river (WHYY, July 14, 2016)

- Fall construction start for Centennial Commons park ‘porches’ in West Parkside (PlanPhilly, August 16, 2016)

- Neighborhood Gardens Trust targets preservation for 28 more gardens (PlanPhilly, October 13, 2016)

- As Norris Square changes, Las Parcelas puts down new roots (PlanPhilly, June 2, 2017)