Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent

Essay

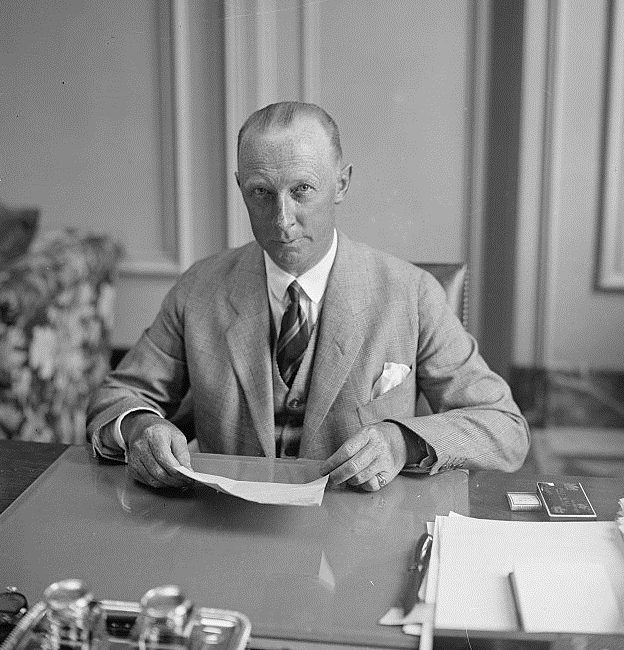

In 1938, the City of Philadelphia amended its charter to create a museum that would collect the city’s material culture and display it for the public. The institution, long known as the Atwater Kent Museum, took its name from radio manufacturer A. Atwater Kent (1873-1949), who purchased and donated the former Franklin Institute building on South Seventh Street for such a purpose. Although older institutions like the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania also documented the history of the city, the Atwater Kent Museum—renamed the Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent in 2010—placed its focus on showcasing historical artifacts for the public. Prior to announcing it would close to the public for financial reasons on June 30, 2018, the museum, its exhibits, and its staff encouraged visitors to use objects to find connections between their lives and the ongoing history of the city.

The Atwater Kent Museum was the second museum dedicated to the history of an individual American city, after the Museum of the City of New York (opened in 1924). Around the same time, other private organizations like the New-York Historical Society and the Chicago Historical Society also created city museums out of antiquarian collections. Unlike those others, however, Philadelphia city government funded the Atwater Kent as the official museum of the city, and its board of trustees included representatives from City Council and the Mayor’s Office alongside members from cultural and academic organizations.

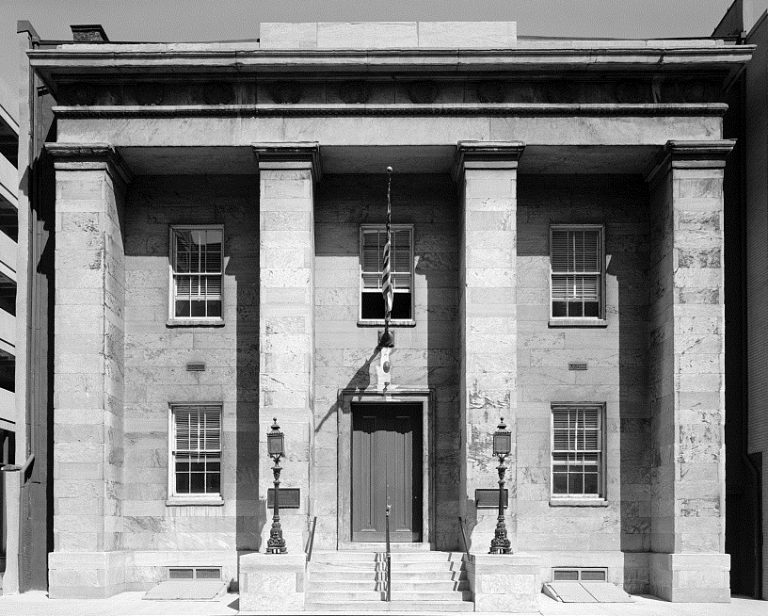

The museum officially opened in 1941 in the building Kent had purchased, a building designed for the Franklin Institute in 1826 by neoclassical architect John Haviland (1792-1852). The institute vacated the premises in 1933 to move to the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Kent’s purchase gave the city a museum, but it also saved the Philadelphia landmark from being bought by Henry Ford (1863-1947) and moved to his collection of historical buildings in Dearborn, Michigan. During the early years of the new city history museum, its collections included artifacts acquired directly from the City, Works Progress Administration (WPA) dioramas, dolls from the Society of Colonial Dames, artifacts from the Friends’ Historical Association, and furnishings from the Bank of North America that had been rescued from a Pennsylvania Railroad warehouse.

Evolving Approaches to Displays

By the 1950s, the museum employed diverse display strategies with audiovisual components, dioramas, and period rooms as well as smaller objects displayed in Art Deco cases. The museum arranged items like toy dolls, nineteenth-century bonnets, and newspapers much the way an art museum showcases decorative objects or the way an anthropology museum organizes exhibitions with discrete, if related, artifacts. Without grand continuous narratives, large-scale objects, and life-size photographs, the Atwater Kent did not yet offer the immersive exhibits that later characterized many history museums.

In its formative years, the museum maintained these exhibits and initiated educational programs to “enable the students in civics and history classes to see that they are a part of Philadelphia life and that they hold a tangible stake in the community’s present and future.” In the 1970s, inspired by the spirit of the Bicentennial, the museum returned to these ideas with a sweeping permanent exhibit covering the three-hundred-year history of the city as well as rotating galleries that traced the development of the city through its municipal services. Mainstays included exhibits about the Fire Department, Police Department, and the local gas and electric companies. The museum also presented temporary urbanist exhibits such as “Fairmount Water Works 1812-1979,” “Fairmount Park,” and “Streets & Squares: 300 Years of Philadelphia Maps & Map-Making.”

At the Atwater Kent, curators used material objects to explore social and structural relationships, document histories of urban planning, and offer systemic perspectives on everyday life in Philadelphia. However, the interaction between people and the city still formed the heart of these exhibits even when they examined seemingly impersonal infrastructures. This emphasis reflected the museum’s increasing attention to the trends of historical scholarship during the 1960s and 1970s, especially the call to write history that included the full range of society rather than simply repeating oft-told stories of great men. The Atwater Kent in this era did little, however, to incorporate people of color into civic narratives, a role taken up separately by the African American Museum created by the city in 1976.

Adapting to the Digital Age

The museum continued to stress the importance of authentic artifacts even in the digital age, for example opening “The Real Thing and Why It Matters” in 2005. This exhibit reemphasized the institution’s ongoing role as the home for Philadelphia’s material culture. Between 2002 and 2009, the Atwater Kent also took on stewardship of the art and artifacts collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, which had chosen to focus on its role as a research library. At the same time, however, financial and operational challenges mounted. From the late 1990s and into the twenty-first century, the museum received less and less funding from a city that was both financially strapped and less willing to fund arts and culture initiatives than it had in the past. The Atwater Kent had been fully funded by the city from 1938 until 1995, but by 2015 less than 20 percent of the museum’s budget came from municipal sources.

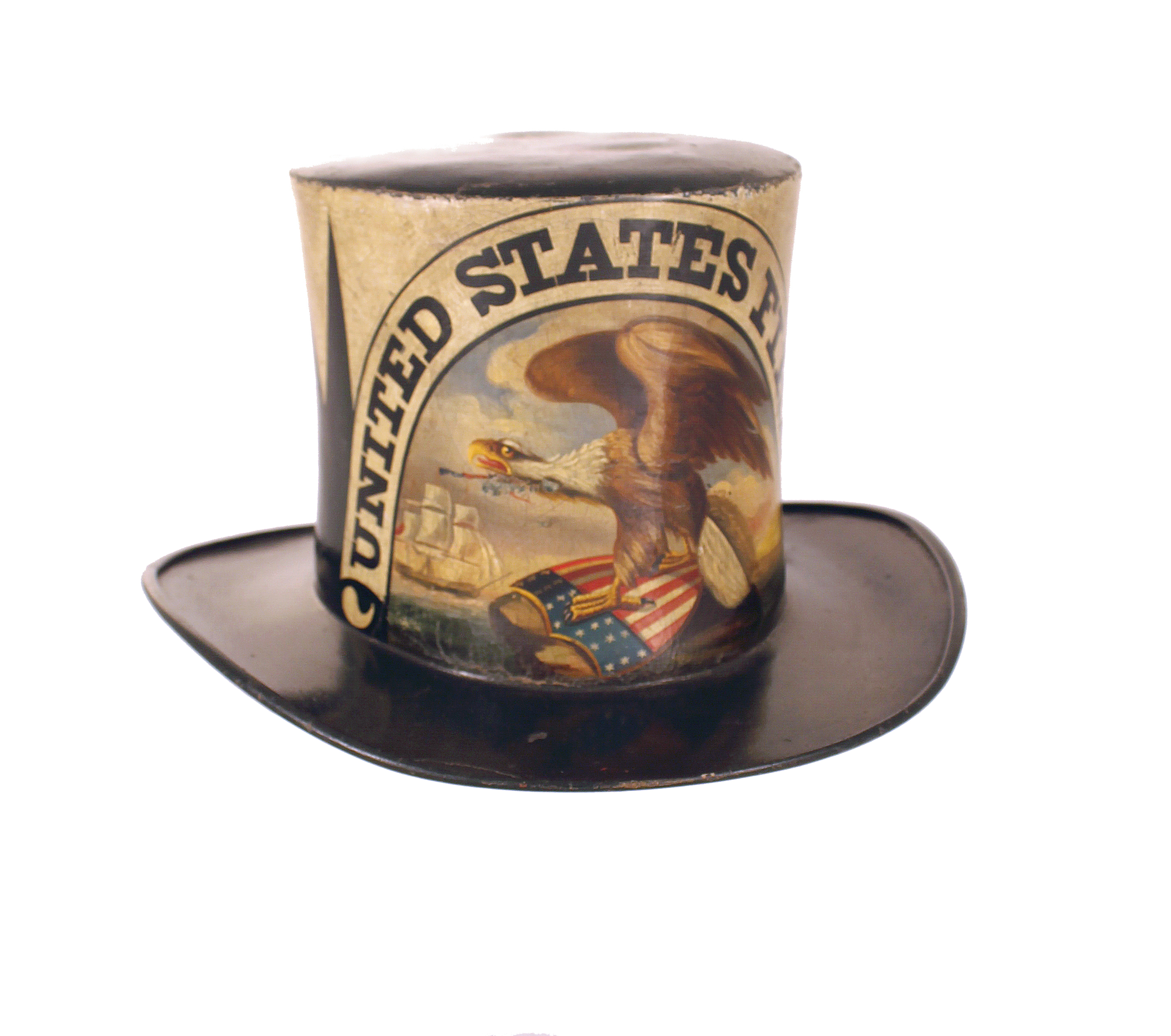

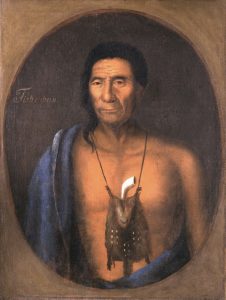

An expensive renovation of the Atwater Kent’s historic building compounded its financial dilemma. Started in 2009, the renovation stretched from an expected one year to three, and the cost ballooned from an estimated $1.5 million to $5.7 million due to unexpected structural issues and expanded plans. During that period, the museum drew attention, much of it negative, for selling art and artifacts to fund the modernization. The museum defended the sales by arguing that artworks lay beyond the scope of its collecting as a history museum and that local items should take priority even if they did not have the same monetary value as other collectors’ items. In this spirit, a portrait by Raphaelle Peale (1774-1825) and trade figures including a beloved cigar store Indian went to new owners while the museum installed exhibits such as “Face to Facebook” and the community-curated Philadelphia Voices gallery.

After completing the renovations, the museum reopened in 2012 as the Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent. As part of a broader reimagination of the museum, the name change adopted in 2010 signaled to visitors what they would find inside. The sale of art and artifacts refined the relationship between the museum’s mission and the collections, but, just as importantly, the auctions funded updates to the system of climate control to assure the preservation of the museum’s artifacts and others on loan. New displays reinterpreted the city’s three-hundred-year narrative with audiovisual technologies that incorporated contemporary perspectives on the city from everyday people of more diverse backgrounds than the museum had ever represented before, including African Americans, immigrants, and other groups. In addition, digital and interactive technologies brought the museum into the twenty-first century by providing new ways for visitors to engage with historical objects while preserving an emphasis on learning from material culture.

Encouraging Visitor Engagement

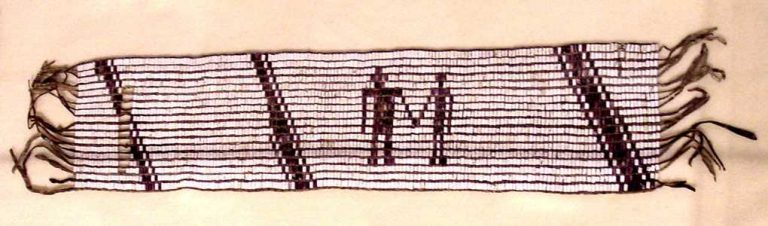

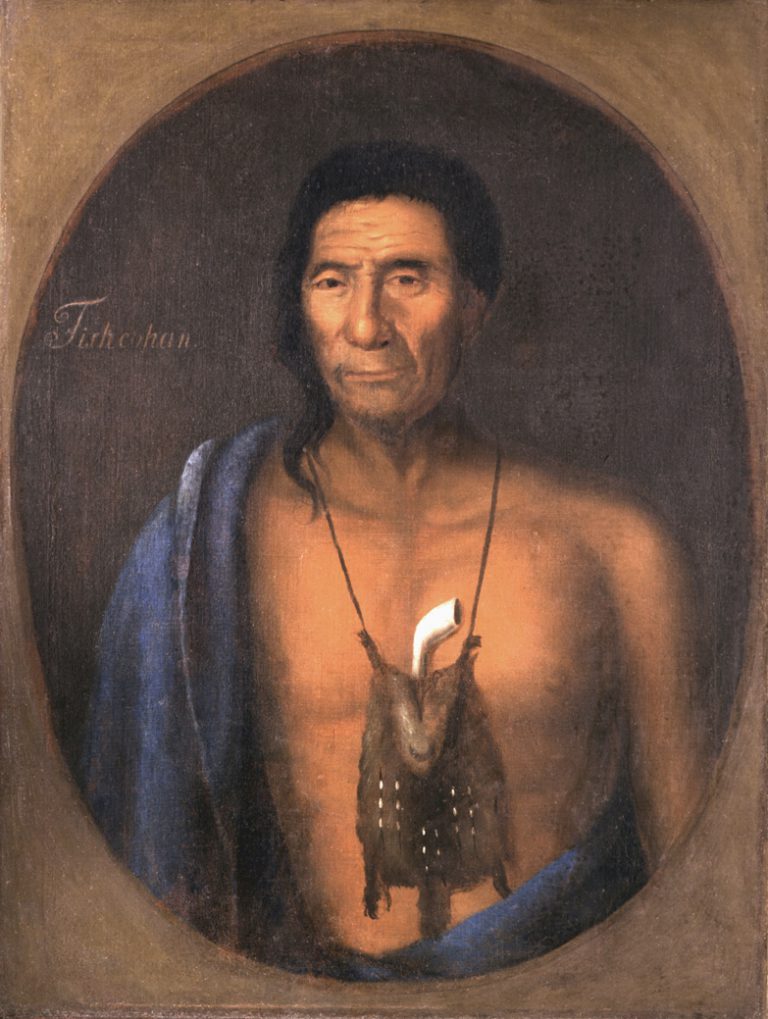

Maintaining the museum’s focus on engaging visitors through material culture, the reopened museum offered a new permanent exhibit titled “The Ordinary, Extraordinary, and the Unknown: The Power of Objects.” In a traditional white-walled gallery, curators placed artifacts like the Wampum belt believed to have been given by the Lenape to William Penn (1644-1718) and a desk that belonged to George Washington (1732-99) together with horrific items like slave shackles and pop cultural items like the boxing gloves used by Joe Frazier (1944-2011). Rather than simply describing whom the items belonged to and what they were for, the exhibit drew on new approaches to public history by asking visitors to imagine the many stories that objects can tell depending on who is looking at them, when, where, and why.

Still, the Philadelphia History Museum struggled for sustainability. Although adjacent to Independence National Park, a destination for millions of visitors every year, the Philadelphia History Museum drew far fewer visitors to its exhibits about the urban environment and the more recent history of the birthplace of the United States. Its quest for funding paled in comparison to the $120 million raised to open a new Museum of the American Revolution in 2017. Seeking new ways to sustain its operations, in 2015 the museum investigated a potential merger with the Woodmere Art Museum with the support of a large grant from the William Penn Foundation, but the partnership ultimately did not move forward. A second merger attempt with Temple University also collapsed, leading the museum to announce it would close its doors as of June 30, 2018, for an unspecified period of time. The action left in doubt the fate of the collections–the true legacy of the institution–and interrupted more than seventy-five years of public access to the museum’s powerful juxtaposition of traditional symbols of the nation with the everyday popular culture of an American city.

Mabel Rosenheck is a writer and historian in Philadelphia. She received her Ph.D. in media and cultural studies from Northwestern University and works at the Wagner Free Institute of Science.

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Northern Liberties' pre-Piazza roots on display at Philadelphia History Museum (WHYY, February 17, 2014)

- Striking photos of turbulent times in Philly history on display (WHYY, August 4, 2015)

- Philadelphia History Museum offers primer on Octavius Catto's life (WHYY, November 16, 2017)

- Philadelphia History Museum shuts its doors indefinitely (WHYY, June 28, 2018)

- Philly History Museum's future may lie with Drexel (WHYY, February 28, 2019)

Links

- Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent

- Online Exhibition: The African American Experience in Philadelphia (Philadelphia History Museum)

- Philadelphia Museum Sells Objects to Get a Face-Lift (NPR, January 5, 2011)

- Atwater Kent (WSHU Public Radio)

- Philadelphia History Museum Budget Testimony FY 2015 (PDF, Philadelphia City Council)

- Philadelphia History Museum Budget Testimony FY 2017 (PDF, Philadelphia City Council)

- Philadelphia History Museum Budget Testimony FY 2018 (PDF, Philadelphia City Council)

- Philadelphia History Museum Budget Testimony FY 2019 (PDF, Philadelphia City Council)

- Uwishunu Philly 101: Philadelphia History Museum (Visit Philadelphia via YouTube)

- Lots to See at the Philadelphia History Museum (CBS Philly via YouTube)

- Philadelphia History Museum Opening Stoop Exhibit (CBS Philly via YouTube)