Department Stores

By David Sullivan | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

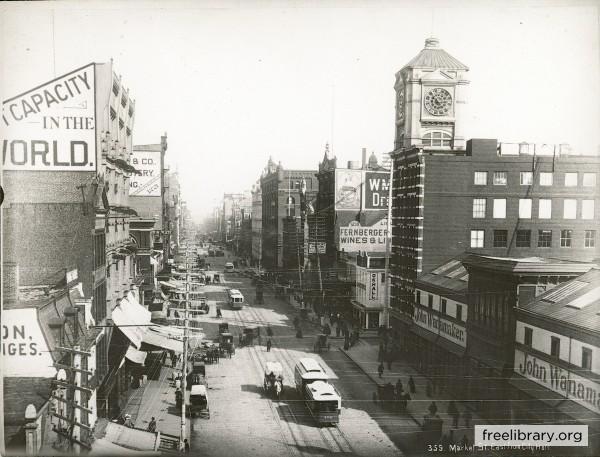

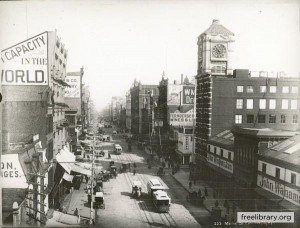

As department stores became central to retailing in American cities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Philadelphia played a major role. Led by John Wanamaker, whose store was a national model, Market Street became home to the giant stores known as the “Big Six,” which were close to rail terminals and subway stations. As the suburbs grew before and after World War II, department stores expanded into developing areas, from the affluent Main Line to working-class Northeast Philadelphia. But while the big stores seemed at their height in the 1950s and 1960s, they were already starting to succumb to new competitors and lifestyle changes, and each decade eliminated one or more of the institutions that once seemed impregnable.

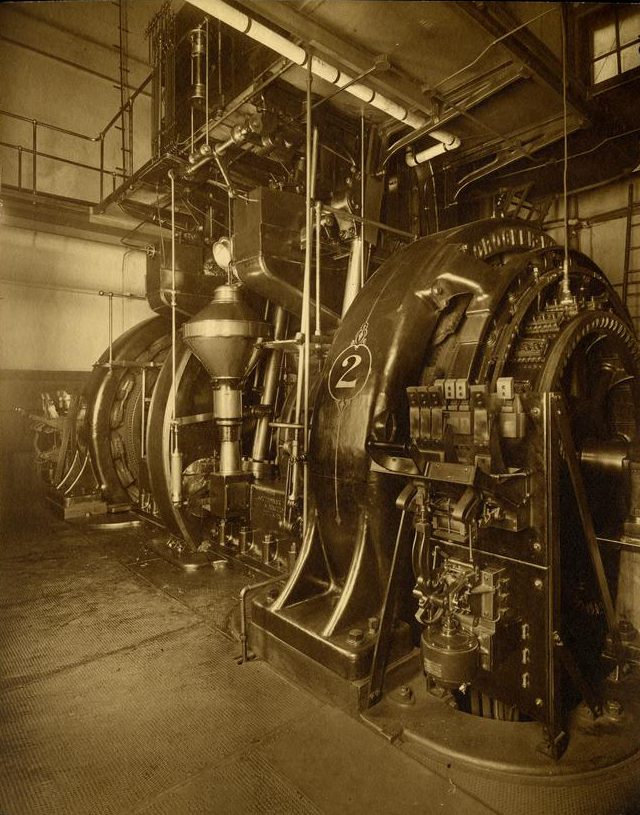

The department store – an emporium selling different kinds of merchandise organized into separate departments with their own accounting – was a Parisian invention of the 1850s that underwent further refinements in the United States. The name “department store” first appeared in the mid-1880s. New technologies, especially mass transportation, made department stores possible as trolleys, elevated rail lines, and later subways brought massive numbers of shoppers to “downtowns” – also a new word. Also important were elevators, fast newspaper presses, and improvements in shipping fashions from London and Paris to foreign shores.

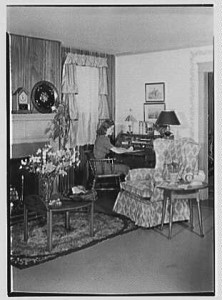

The department stores’ preeminence came not just from their size, but from how they influenced culture. In addition to filling immediate wants, the stores created enticing windows, in-store displays, and advertising that fueled shoppers’ aspirations. As the United States became a land of immigrants and cities, department stores displayed how Americans lived, or how they might live, while giving them choices about exactly how to do so. Shoppers flocked to Wanamaker’s store and its imitators locally and around the nation, drawn by low prices, vast merchandise, and innovations such as charge accounts and tea rooms – the latter among the stores’ most fondly remembered elements. Department stores learned to make use of decoration and pageantry, not only lifting shopping out of the mundane but solidifying their roles as community institutions.

Dry-Goods Stores Grow Up

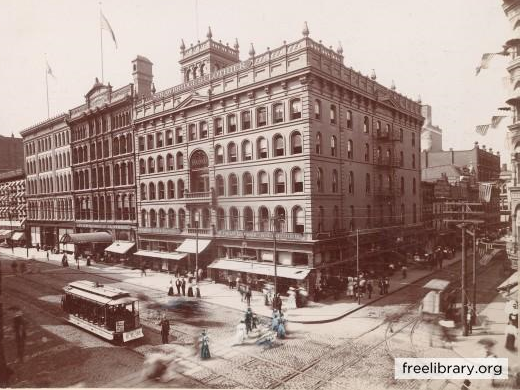

Most U.S. department stores grew out of dry-goods stores, which in 1860s Philadelphia centered on two main areas – on Second Street, and on Market and Chestnut Streets west from Eighth Street. The development of City Hall at Broad and Market Streets and the surrounding railroad stations in the 1870s and 1880sthen pulled retailing west, although Eighth and Market remained the eastern anchor of department stores into the late twentieth century.

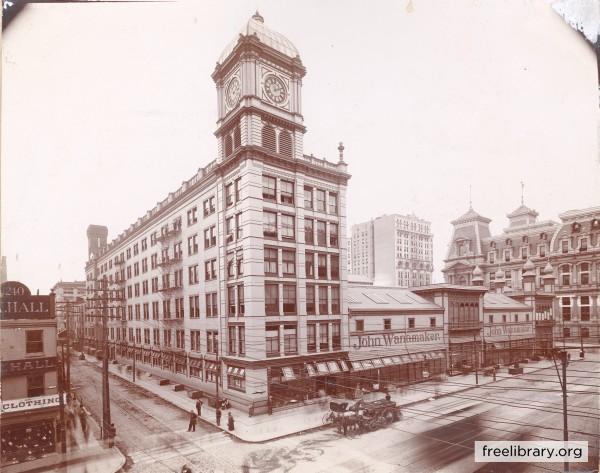

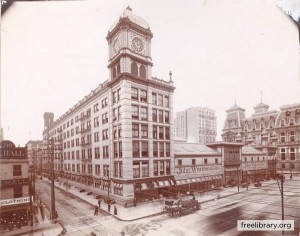

John Wanamaker (1838-1922), who grew up in Grays Ferry, dreamed of becoming a merchant prince in the manner of Alexander T. Stewart (1803-1876), the New Yorker whose Marble Palace was a Manhattan landmark. In 1861 Wanamaker became a partner in Oak Hall, a manufacturer and retailer of men’s clothing at Sixth and Market Streets, and saw success in manufacturing clothing for Civil War soldiers. By 1871 his men’s store was the largest in the country. Seeing opportunities in the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, which would draw people to rail depots around City Hall, Wanamaker purchased an old freight depot southeast of Centre Square and opened his “Grand Depot.” By fair’s end, Wanamaker and his store were becoming nationally known.

Wanamaker, a devout Presbyterian, represented many of the conflicts between commerce and piety produced by the new consumer culture. His advertising – he is credited with the first full-page newspaper ad – emphasized the goods on sale but often contained moral aphorisms he wrote, such as saying his “New Kind of Store… came to life at the cry of human need… It rehabilitated the people in their rights by the new deal we instituted.”

Wanamaker and others presented their stores as not simply businesses but as community institutions. Nearly all emphasized that their job was not simply to sell, but to offer a high level of customer service. Fair treatment of staff was emphasized by cutting work hours and establishing clinics, clubs, and summer camps. The underlying belief was that a happy employee would more pleasantly serve the customer – and that service, as an expression of Christian feeling or as a substitute for it, allowed the newly middle-class shopper to buy a little more without feeling hedonistic.

Wanamaker Success Spurs Imitators

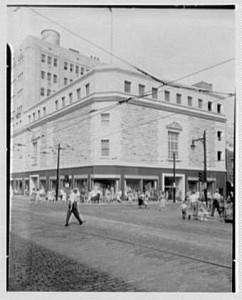

As Wanamaker set national precedents, other Philadelphia merchants took note. Strawbridge & Clothier was a dry goods house founded in 1868 on the northwest corner of Eighth and Market, where it remained until it closed in 2006. A partnership of two Quaker families, who remained in control until 1996, Strawbridge’s emphasized low prices, high quality, and cash sales. It prided itself on fair dealing and its sense of Philadelphia history, as shown by its “Seal of Confidence,” evoking William Penn’s treaty with the Indians, introduced in 1911.

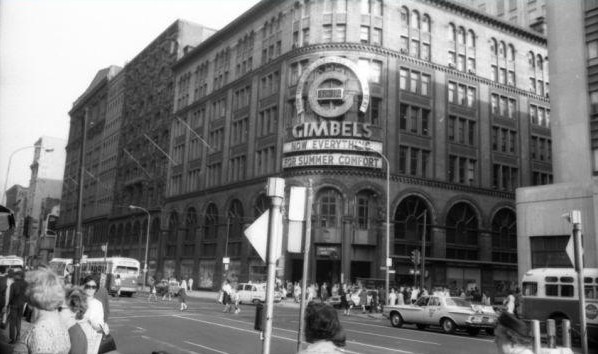

Directly across Market from Strawbridge was Gimbel Bros., a firm that began in Vincennes, Ind., in 1842. The sons of trader Adam Gimbel (1817-1896) moved through small towns in Illinois until opening their first big-city store in Milwaukee in 1887. In Philadelphia in1894 they purchased the large store built by Cooper & Conard at Ninth and Market that had been operated briefly by Granville Haines. Most of the Gimbel family moved to Philadelphia and made it their base of operations for years, even after opening in New York in 1910.

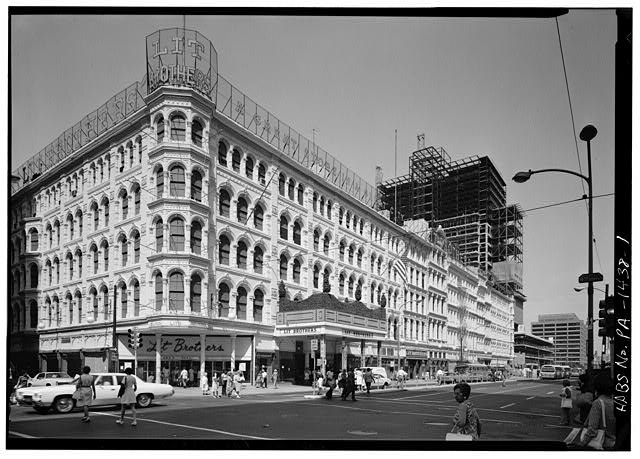

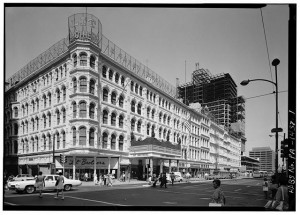

While Gimbels walked the line between upscale and downscale, the rest of the Big Six went straight for the lower-to-middle market. The third store at Eighth and Market was Lit Bros., famed for its block of five-story buildings and its mottos, “Hats Trimmed Free of Charge” and “A Great Store in a Great City.” Lits grew out of a dress store opened on North Eighth Street in 1891 by Rachel Weddell (1858-1919), who became known for trimming hats free if the materials were bought from her. Two years later, her brothers, Samuel (1859-1929) and Jacob Lit (1872-1950), expanded it into a department store.

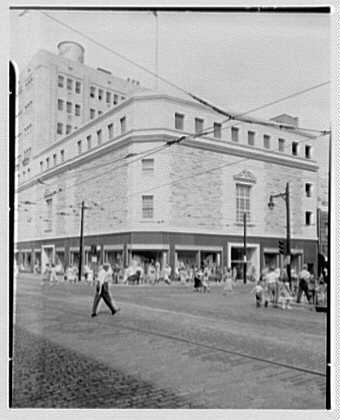

Completing the Big Six were two stores at Eleventh and Market, N. Snellenburg & Co. and Frank & Seder. Snellenburg’s began on South Street in 1873 and moved uptown in 1889. The last store to arrive, in 1915, was Frank & Seder, a branch of a Pittsburgh store that also operated in Detroit. Eventually twelve floors, it was the city’s tallest store except for Wanamakers. In Philadelphia’s neighborhoods, meanwhile, Frankford and Kensington also had small local department stores and Germantown was home to George Allen Inc. and C.H. Rowell.

1911: Taft Dedicates Wanamaker’s

Wanamaker took steps to stay ahead of the competition. In the early twentieth century, he commissioned Daniel H. Burnham (1846-1912), architect of the Chicago Columbian Exposition, to design a new fourteen-story store on the site of his Grand Depot. Work progressed in three parts, with internal divisions that remained visible in the completed store. The building was opened in 1911 with an address from President William H. Taft (1857-1930), making it the only department store to be dedicated by a sitting president. Also, like the Gimbels, Wanamaker invaded New York, buying the store of his former idol, Stewart.

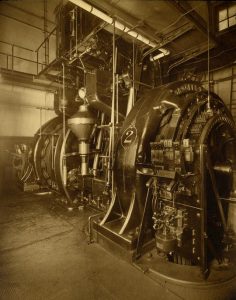

The giant stores became stages for pageantry that underscored their role in civic life and the culture of downtown. Wanamakers installed a 10,000-pipe Grand Organ from the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, added 8,000 pipes, and on occasion brought in the Philadelphia Orchestra to accompany it. At peak shopping seasons, Wanamakers and other stores re-created the richness of Rome or the Belle Epoque. To balance the frivolity, during each Lent the Wanamaker store exhibited paintings of Jesus before Pilate and on the cross.

For Christmas, store windows drew families to Market Street to see the tableaux of animated dolls skating, opening presents, and writing lists to Santa, who awaited upstairs. Inside, Lits created the Colonial Christmas Village and Strawbridge offered the Dickens Christmas Village. Wanamakers’ Christmas Light Show, introduced in 1955, packed the Grand Court hourly with children and parents watching the antics of Frosty, the Sugar Plum Fairy, and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer – a character created by the national department store chain Montgomery Ward & Co. in the 1930s.

Although generations of Philadelphians cherished these traditions, as early as the 1920s automobile ownership and suburban housing development signaled a new era in which retailing shifted away from downtowns. In Camden, local stores in the downtown area, such as Munger & Long and Baker-Flick, began to disappear around the time of the opening of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in 1926, briefly leaving only a J.C. Penney store downtown. Although Philadelphia’s main stores continued to expand in Center City, they also opened branches, at first small and confined to resorts and affluent suburbs. Strawbridge responded more assertively by opening some of the city’s first branch department stores, at Suburban Square in Ardmore in 1930 and just outside Jenkintown on Old York Road in 1931. Frank & Seder also adopted a suburban strategy, opening a store near the 69th Street Terminal in Upper Darby in 1929.

Lits Is Sold

Most of the Big Six remained family-owned, but Lits was sold to one of the new chains of department stores being organized in the 1920s, City Stores, an amalgamation of three stores in the South and the Goerke family’s operations around Newark, N.J. The Depression put then City Stores into the hands of Albert Greenfield’s Philadelphia-based Bankers Securities Corp., which broke off Lits as a separate unit.

When suburban growth resumed after the Great Depression and World War II, department stores continued their expansion. Strawbridge’s and Wanamakers opened branches in Wilmington, whose department stores were weakening. Lits bought a store in Trenton, took over from Frank & Seder in Upper Darby, and built new stores in the Northeast and in Camden. Snellenburg’s – another part of the Bankers Securities empire since 1951 – went to Lawrence Park, Willow Grove, and South Philadelphia, and bought the largest store in Atlantic City. Wanamakers branched out to Jenkintown and Wynnewood, and Strawbridge also went to Springfield, Delaware County.

The cost of staying competitive was too much for Frank & Seder, which withdrew from Philadelphia in 1953 and went out of business entirely in 1959. Next to fall was Snellenburg’s. In 1962, its branches were rebranded as Lit’s, leaving just the downtown store. One day, the store abruptly closed, with customers being ordered onto the street at 2 p.m.

On the other hand, Strawbridge in 1961 became one of the anchors in Cherry Hill Mall, the first enclosed mall on the East Coast and the second in the nation. Strawbridge also responded to the rise of discounters, which were stealing department stores’ business, by creating the Clover division, named after the family’s estate, Cloverly, in East Falls, as were the widely anticipated Clover Days sales.

Slowly, the Tide Turns

While department stores seemed to be booming in the 1960s, they had in fact passed their peak, as discounters, malls, and big-box stores offered wider selections at lower prices and with lower fixed costs, and more new competitors moved in from other cities. Macy’s entered the field in 1962 through its Bamberger’s division at Cherry Hill Mall. High-fashion New York stores such as Saks Fifth Avenue, Lord & Taylor, and B. Altman & Co. were already on the Main Line, and Bloomingdale’s opened local branches.

The national chains of Sears, Roebuck & Co. and J.C. Penney Co. had longtime local operations but had never tried to compete in Center City. Sears had one of its national catalog centers in a huge building on Roosevelt Boulevard, and its longtime chairman, Lessing Rosenwald (1891-1978), lived in Montgomery County. Sears’ executive staff remained at the company’s home base in Chicago, although it opened one of its first retail stores on the Admiral Wilson Boulevard in Camden. Penney’s was even less visible, though it had stores in Germantown and on 69th Street (and later in the Gallery in Center City).

For Philadelphia’s department stores, decline and transition quickened in the 1970s and 1980s. Lits fell in 1977. The Philadelphia-area Gimbels stores were purchased by the Allied Stores chain and assigned to its Stern’s division. By 1989 Stern’s was done in Philadelphia, and the Reading-based Boscov’s Department Stores Inc. began picking up vacated stores. Boscov’s also for a number of years sponsored the city’s Thanksgiving parade, which had been established by Gimbels in 1920 as the first celebration of its kind in the nation.

Even Wanamakers was sold, first in 1978 to Carter Hawley Hale Stores from California and then in 1986 to Woodward & Lothrop, a Washington store owned by Detroit mall developer Alfred Taubman (1924-2015). After “Woodies” went bankrupt in 1994, Wanamakers became part of the Hecht’s division of May Department Stores, which then bought Strawbridge & Clothier in 1996.

Finally, in 2005, Federated Department Stores bought May. The firm renamed all of its stores across the nation as Macy’s, except for Bloomingdale’s stores. Thus, in 2006, Macy’s came to Market Street. The Strawbridge location closed and Macy’s moved into the store built by John Wanamaker. Macy’s pledged to maintain and improve the Christmas Light Show that had delighted generations of children and adults, and it remained a tradition to meet “at the Eagle” – a statue brought back to Philadelphia from the St. Louis world’s fair by Wanamaker, the brickmason’s son whose words, still inscribed on a column on the main floor of his store, spoke to a vanished era in retailing:

Let those who follow me continue to build with the plumb of honor, the level of truth, and the square of integrity, education, courtesy and mutuality.

David Sullivan is an editor at the Philadelphia Inquirer. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2011, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- "Random Act of Culture," 2010: The "Hallelujah Chorus" by the Opera Company of Philadelphia with the Wanamaker Organ (YouTube)

- John Wanamaker and his "New Kind of Store" - A Lesson Plan (ExplorePAhistory.com)

- John Wanamaker [Industries] Historical Marker (ExplorePAhistory.com)

- John Wanamaker [Great Depression] Historical Marker (ExplorePAhistory.com)

- John Wanamaker (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment

- Better Philadelphia Exhibit (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)