Historical Society of Pennsylvania

By Alea Henle

Essay

Established in 1824 to gather and protect historical materials, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP) developed from a learned society and gentlemen’s club into a professional institution with a robust publication program and an extensive research library. Over the decades, the society also expanded its activities to support education and public history programs and coordinate with related organizations.

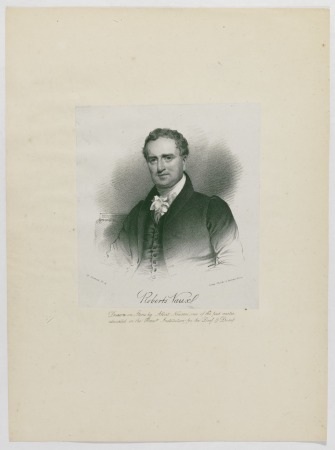

Lawyer Roberts Vaux (1786–1836) and other wealthy Philadelphia men founded the Historical Society during the triumphal tour of the United States by the Marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834), the upwelling of celebration and remembrance attendant on the upcoming fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, and celebration of the 142nd anniversary of the arrival of William Penn (1644–1718) in Pennsylvania. Attorney William Rawle (1759–1856) became the first president.

Members came from the upper middle classes, as with earlier historical societies established in Massachusetts (1791), New York (1804), and other northeastern states; lawyers predominated over ministers among the early members. French-born Peter S. Du Ponceau (1760-1844) served as the society’s second president, from 1837 to 1845, and Charles J. Stillé (1819–99), of Swedish descent, as the eighth (1892–99). Otherwise most board members were men of Anglo-American descent well into the twentieth century. The Historical Society served as a gentlemen’s club, offering a forum for exchange of historical papers and research. A voluntary association with nominal dues, it relied on the energy and support of members.

The Early Years

The Historical Society first received housing courtesy of the American Philosophical Society, then moved to rooms in the Athenaeum of Philadelphia in 1847. Records of the early decades reveal meetings canceled due to a lack of quorum, periods of inactivity, and irregular publication of its Memoirs, which contained miscellaneous articles including excerpts copied from William Penn’s correspondence. Nevertheless, the society gathered collections documenting Pennsylvania history in general and Penn in particular. Correspondence with Penn’s heirs in 1833 resulted in gifts that invigorated the society’s collecting.

Biases—in regard to race, class, and gender in particular—restricted the society’s developing collections. Members focused upon documenting the history of the worlds they knew, thus their collecting activities centered on politics, religion, civil society, and leading figures. The society avoided addressing materials documenting the history of slavery and Americans of African descent, whether free or enslaved, although it did gather printed abolition tracts. The outbreak of the Civil War initially reduced the society’s finances and attendance. However, in 1862 the society extended membership to women and individuals born outside of the United States, which revitalized the society while reducing the influence of the pro-Southern contingent. The broader membership had an immediate impact on collecting, although biases remained.

Over the second half of the nineteenth century, the society became as much research library as gentlemen’s club. Collections grew to the point where, in 1871, the society leased the Pennsylvania Hospital’s Picture Building on Spruce Street. Two years later, the society obtained sufficient funds to purchase a sizable collection of Penn’s papers. The society participated in organizing the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, marking a shift towards engagement with public history. Member Henry Armitt Brown (1844–78) delivered speeches celebrating Revolution-era leaders on the lecture circuit, and the society published brief biographies of Declaration of Independence signers in its new quarterly journal, the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, first published in 1877.

Thirteenth and Locust Streets

Outgrowing the Picture Building, society officers raised funds to purchase a mansion and adjoining lot at Thirteenth and Locust in 1883. The society built annexes in 1890 and 1905, then erected a new fireproof building in 1910, which continued to serve as the entry point to the society after a series of renovations in the mid and late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Publisher and bookseller Townsend Ward (1817–85) was elected librarian in 1851 and two years later became the society’s first paid staff member. By 1921, librarian Thomas Lynch Montgomery (1862–1929), a leader of the American Library Association, supervised a staff of thirteen including eight women. The society hired Jane C. Wylie (1853?–1925) in 1891 and she rose to head the manuscripts department. Staff learned on the job rather than through formal training; staff shortages contributed to a chronic cataloging backlog. Ongoing collecting continued to focus upon the lives and experiences of upper-class Americans of European descent.

In the 1930s, librarian Julian P. Boyd (1903–80) pushed the society to embrace progressive approaches to historical scholarship and become a professional scholarly society. In 1934, early in his tenure, he met with black Philadelphia printer Leon Gardiner (1892–1945), who contributed his collections, including extensive materials from the defunct Afro-American Historical Society, also known as the American Negro Historical Society. Five years later, Boyd facilitated the development of a statement that refocused the society’s mission on inclusion of all groups regardless of race, ethnicity, class, or religion.

Twentieth-Century Expansion

By the latter half of the twentieth century, the Historical Society expanded to include a diverse array of initiatives. Under the leadership of Nicholas Wainwright (1914–86), who served in several capacities, including editor, librarian, and director, the society formed agreements with commercial publishers in the 1960s resulting in facsimile and microfilm publications of Indian Treaties (1963), the Pennsylvania Gazette (1968), and African American–related reprints (1969). By 1976, the society held the papers of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, a process begun in the 1920s. The society also hosted related projects. In the 1970s, it provided space for the William Penn Papers project, which prepared first a microfilm and then a letterpress edition. In the 1980s, it supported the Pennsylvania Newspaper Project, another microfilming project, and in the 1990s the Biographical Dictionary of Early Pennsylvania Legislators project, although a dispute over the latter’s autonomy led it to relocate to Temple University. In addition, the society developed a closer relationship with its neighbor, the Library Company of Philadelphia, producing joint exhibitions and initiating a fellowship program to support scholarship.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the society moved to hire professionally trained library staff and added positions focused on educational programming. Members also elected their first female and African American board members: Philadelphia Museum of Art curator Beatrice Garvan (b. 1929) in 1966 and scholar Charles L. Blockson (b. 1933) in 1976. In 1990, museum administrator Susan Stitt (1942–2001) became the society’s first female president.

Society leadership played a large role in shaping and reshaping the society. Historian Peter Parker (b. 1936), first hired as head of the manuscript department in 1970, served as director in the 1980s; under his guidance, the society embraced public education through exhibits, lectures, and outreach to schools. Under Stitt, supporting research became a higher priority. She also made the controversial decision to transfer the society’s art and artifact collection to the care of the Atwater Kent Museum; this was completed in 2002 with official ownership transferred in 2009. David Moltke-Hanson (b. 1951), who succeeded Stitt and had previously served as director of the Southern Historical Society, focused attention on education, facilitated the launch of Pennsylvania Legacies in 2001, and secured grants for major archival projects. In 2002, the Historical Society successfully merged with the Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies (founded 1971), resulting in deeper and more diverse collections.

The society had a long symbiotic relationship with the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania (founded 1892); Genealogical Society members held membership in the Historical Society, which in turn provided housing and research support. Amid monetary woes in the 1990s, officers attempted to merge the societies, but failed. The two organizations developed an alliance in 2006, depositing the Genealogical Society’s holdings with the Historical Society. Genealogy became an increasingly important focus for the society in the twenty-first century.

Organized as a learned society and gentlemen’s club, successive generations of leaders expanded and contracted the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s spheres of action. Over the course of nearly two centuries, the society transformed into a professionally staffed institution and amassed extensive, diverse collections while struggling with how best to serve the public good and support historical research.

Alea Henle is head of public services librarian at Western New Mexico University. Her research interests explore how efforts to preserve materials for history have shaped what survived. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History