Machining and Machinists

Essay

Hundreds of machine shops, large and small, built and maintained Philadelphia’s position as the “Workshop of the World” through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the city and beyond, especially in Conshohocken, Pottstown, Phoenixville, Chester, and Camden, machining made the Delaware Valley a hub of foundries, craft shops, mills, workshops, and manufactories. During the latter half of the twentieth century, however, rising labor costs and international competition led to the decline of this segment of the region’s economy.

Machining activities in Philadelphia began in the colonial period when craftsmen used hand tools to produce individual items to customer specifications. Furnacemen cast iron, brass, tin, and pewter items that finishers like blacksmiths, tinsmiths, and carpenters turned into consumer goods. One of the first metalworking operations in the city was Johnson Type Foundry, which opened at Seventh and Sansom streets to provide type settings to printers. It operated until 1897, when it became part of the American Type Founders Company, which ceased operations in 1993.

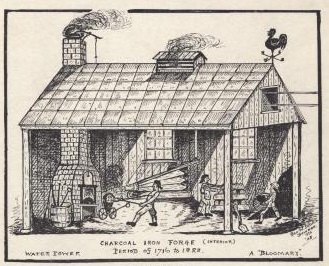

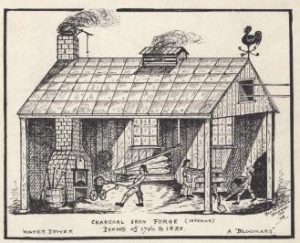

During the American Revolution a Continental Arsenal employing over one hundred men and women initiated large-scale forging and finishing in the city. Private craftsmen and forges also supplied finished metal products to the army. Numerous regional forges and furnaces produced metal products for Colonial and Revolutionary Philadelphia, including Colebrookdale and Hopewell near Pottstown and Durham near Easton.

Metalworking and manufacturing in the region grew after the war so that by 1800, 42 percent of Philadelphia’s sixty-eight thousand people worked in industrial activities. Outside the city in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, French Creek Nail Works began operations in 1790. This became Phoenix Iron Works in 1855 and expanded to producing metal consumer products. J. Wood and Son Iron opened in Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, in 1832, leading to a blooming of metal working and finishing shops and the town’s nickname, Ironborough. Plate and nail machining mills opened in Pottstown in this period. The Federal Slitting Mill, founded in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, in 1793 laid the foundations that would become Lukens Steel. In this period, only small-scale craft operations developed in Camden, New Jersey, because investors focused more on transportation and trade.

Machining and the Mint

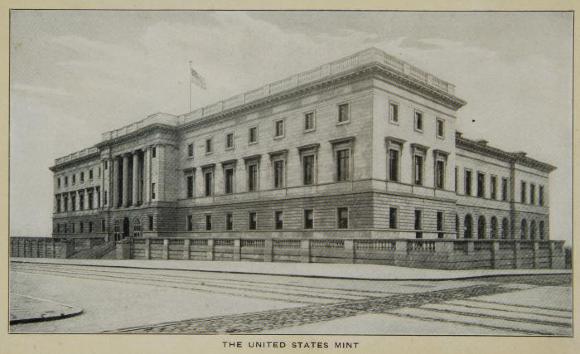

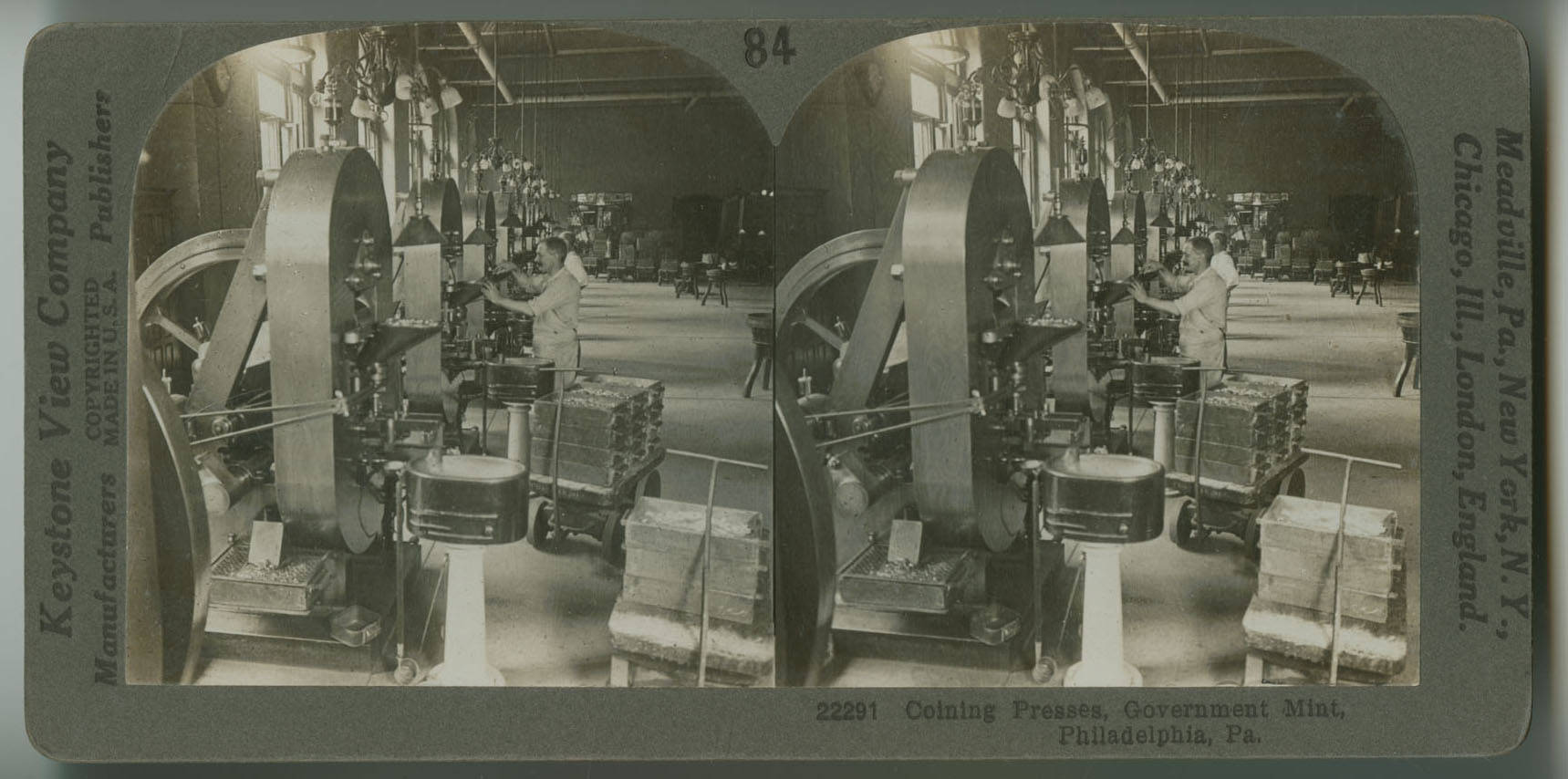

The national government played a key role in Philadelphia machining after the Revolution. The Federal Mint opened in 1792 on East Seventh Street above Market (later moving to Juniper and Chestnut Streets in 1833, to 1700 Spring Garden Street in 1901, and finally to Fifth and Arch Streets in 1969). The later versions of the mint grew to be the largest such operations in the world and turned out 501 million coins annually. The Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, which grew to include numerous machining shops, began operations in 1801 at Delaware Avenue and Federal Street. It moved to League Island in 1871 and produced and repaired naval vessels until decommissioned in 1995. In 1816, the federal government opened Frankford Arsenal, which forged and machined mostly small arms ammunition until its closure in 1977. Its operations, however, also included milling, optical grinding, and electroplating.

In the nineteenth century the development of machine lathes, milling machines, drill presses, and cutting tools allowed laborers to turn, bore, drill, mill, ream, and shape items faster with more precision. The result in Philadelphia was the rapid expansion of machining operations to match the rise of large manufacturing sites, building construction, and commercialism. Operations like the Baldwin Locomotive Works, the William D. Rogers Carriage Factory, and the Cramp & Son’s Shipyard required support from small item forgers and finishers. For commercial buildings and private housing, machining provided items like pipes, lumber, nails, and other castings. The growing population of the city purchased all types of machined products like irons, kitchen utensils, stove plates, and sewing needles.

Machining firms that answered the growing Philadelphia economy varied in size and product. The Point Pleasant Iron and Brass Foundry, founded in 1809, and the Cresswell Ironworks, opened in 1835, supplied custom castings for buildings, bridges, plumbing, and transport. Henry Troemner & Company, founded in 1840, manufactured weights, measures, and scales for doctors, pharmacists, and banks. One of its biggest clients was the Philadelphia Mint. S.S. White Dental Works, founded in 1844, made false teeth and other oral health products. In Camden, Richard Esterbrook’s steel pen factory and the Camden Iron Work became suppliers of various consumables. Likewise, in Chester, Pennsylvania, machinists and craftsmen took advantage of the rail line between Philadelphia and Baltimore to furnish items to both markets.

By the time of the Civil War, manufacturing employed nearly half of Philadelphia’s population (roughly 210,000 people in a city of about 500,000). Frankford Arsenal was critical to the war effort, as were firms like Sharp and Rankin, which machined breech-loading rifles, and Cramp & Son’s, which built the USS New Ironsides. During this period machining operations began in Norristown and Bridgeport and worked metal supplied from Pottstown and Phoenixville. Phoenix Iron cast and worked artillery for the Union and in the process developed the Phoenix cylinder, which revolutionized metal construction. It also spun off the Phoenix Bridge Company, which remained in operation until 1962.

Post-Civil War Growth

The Delaware Valley machining industry continued to grow in the decades following the Civil War. In Philadelphia, new foundries included Yale & Town, American Machine Works, the Eagle Bolt Works, and Fox Foundry. Tacony Iron Works, founded in 1881, cast the William Penn statue that was placed atop Philadelphia City Hall. Penn Steel Casting and Standard Steel Casting opened in Chester during the period, while in Camden Joseph Campbell opened a canning factory and several railroads built repair yards.

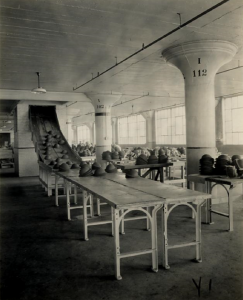

The most well-known of Philadelphia’s new machine and casting shops was Disston & Sons Keystone Saw Works, founded in 1872. Disston became the largest saw producer in the world making large commercial saws, carpentry tools, and household saws. Disston became famous for its company housing for workers and community building projects. It was also the first company in the nation, in 1906, to use an electric furnace to cast crucible steel.

Machining, like Philadelphia manufacturing generally, remained close to its crafts roots throughout the nineteenth century. Sixty-two percent of the city’s 9,100 manufacturing firms employed between one and five people. Skills passed from one generation to another within families, or companies trained workers recommended by employees. Guilds of skilled workers protected their rights to manage apprenticeships and training that limited access to machining. Outwork continued to be done at home, and street peddlers were widespread, offering custom products and finishing.

The small size, specialization, and plethora of machine shops had several implications. Machine workers retained craft skills lost by workers in industries adopting factory production. Workers had little power to organize themselves, either by specialty or business. And the number of African Americans, immigrants, and women in machining remained low. By 1900, 55 percent of the machining workforce was still white, native-born men.

Schools Promote Diversity

Diversity within the ranks of machining workers was driven by the Philadelphia School District and private schools looking to increase access to skilled jobs. In 1880, the district founded the Industrial Arts School to provide public education in trades. Five years later the Philadelphia Manual Training School was founded, and by the 1890s the city had a dozen manual arts schools. By the 1910s most high schools offered vocational training. Girard College created an industrial school to offer higher levels of training, and Drexel Institute was founded in 1891 for the same reason. Educational opportunities competed with guild and corporate training, allowing women, immigrants and African Americans at last to enter the skilled labor force.

The city’s skilled workforce drove expansion among local firms and investment by regional firms. Max Levy (1857-1926) came to the city from Baltimore and expanded his glass engraving business to photoelectrotyping, acid engraving, grinding, and x-ray plate production. Budd Company started in 1912 to manufacture auto bodies and railroad components. Its most famous product was the original Metroliner car that became the backbone of Amtrak’s passenger train operation. Arthur Atwater Kent (1873-1949) began building telephone components and voltmeters in Massachusetts, but moved into manufacturing radios in Philadelphia in 1923; until 1936 his company machined tubes, receivers, and other radio components.

Local markets like Camden, Chester, and Pottstown also saw development in this period. In 1901, Eldridge R. Johnson (1867-1945), a machinist working with the Berliner Gramophone Company in Philadelphia, started his own sound recording company in Camden, the Victor Talking Machine Company. RCA (Radio Corporation of America) acquired Victor in 1929. Ford Motor Company built an integrated steel mill and machining plant along the Delaware River in Chester in 1927. Bethlehem Steel entered the regional market by taking over sites in Pottstown and expanding them to supply Philadelphia machinists.

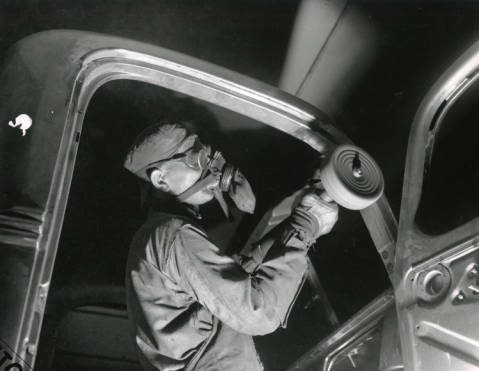

Philadelphia machining reached its pinnacle during the two world wars. Providing a vast array of items for the military ensured a change in the composition of the machining workforce. Atwater Kent produced artillery fire control equipment, while Fayette R. Plumb machined entrenching tools in World War I. Nice Ball Bearing machined ball bearings for trucks, gun mounts, and aircraft pulleys for both wars. World War II spurred creation of the Tacony Ordnance Company and the Tacony Army Plating Plant from companies decimated by the Great Depression. Frankford Arsenal was called on for ammunition, and most firms, like O.P. Schumann, refitted their works to manufacture military goods like tanks, tank guns, artillery, and weapon parts. Cramp shipyard built several cruisers and destroyers, while Philadelphia Naval Shipyard built the battleships West Virginia, New Jersey, and Wisconsin. And the U.S. Naval Aircraft Factory was charged with producing a remote control turbojet air-to-air missile. Another innovation from the period came from Dodge Steel, which replaced Tacony Iron. Foreman John Williams developed a casting process using an apparatus that maintained the pressure of molten metals during a cast. The level of production necessary to support the war effort required the hiring and training of unskilled labor. As a result, women, immigrants, and African Americans became a significant part of the machining workforce.

War and Shipbuilding

Other segments of the Delaware Valley also contributed to American efforts in both world wars. Chester’s Sun Shipbuilding and Dry Dock went into operation in 1917 just in time to build seven cargo ships for the military. Having grown substantially by 1940, Sun produced 318 various types of cargo vessels during World War II. During that war New York Shipbuilding in Camden built, among other ships, nine light aircraft carriers and the battleship South Dakota, while Bethlehem Steel used its Pottstown plant to cast and machine both naval and field artillery.

The rise of larger firms, increasing diversity, and economic collapse during the Depression led to greater organization among machine workers. Skilled workers demonstrated and struck in 1893 and 1903 for better pay and against child labor, but generally, the familial nature of craftwork made unionizing difficult. By the 1910s local guilds became more formalized in organizations like the Iron Molders Union, Amalgamated Steel Metal Workers, and Philadelphia Engravers Union, but they did not have much political influence. The Great Depression, however, challenged the labor status quo and took advantage of changing worker demographics brought on by education. Closures and consolidations cut the number of firms in Philadelphia to 5,760, each with an average of fifty-three workers. This fostered organization and activism among workers. The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and American Federation of Labor (AFL) molded local groups into larger unions such as United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers Union with the power to press for better conditions and pay. They succeeded, securing wage increases totaling 500 percent between 1950 and 1980.

The city’s casting, machining, and finishing workforce of 900,000 in 1950 dropped precipitously by century’s end. Rising wages and foreign competition undermined machining in Philadelphia following World War II. As Europe and Japan recovered from the war, they became producers of custom made consumer goods, and inexpensive machined products. Asia also became a hub for steel production, as first Japan and then China dominated its manufacture. Lower Asian labor rates and access to inexpensive resources led large domestic manufacturers in shipbuilding, electronics, and automobiles to relocate overseas. Machining concurrently declined as fewer large operations remained and labor rates made foreign products more attractive. By 1980, the number of Philadelphians engaged in manufacturing fell to 24 percent, or roughly 380,000. The majority of these lost jobs were skilled finishers and machinists.

While some urban firms moved to the suburbs, most left the region entirely or went out of business. Henry Troemner moved to West Deptford, New Jersey, in the 1960s at the same time that O.P. Schumann moved to Warminster, Pennsylvania. Baldwin Locomotive, which had left Philadelphia starting in 1928, went out of business in 1972, as did Sun Shipbuilding in 1982 and Budd Company in 2002. Ford left Chester in 1961, relocating its regional manufacturing to Mahwah, New Jersey. Likewise, in 1992 RCA (owned by General Electric) left the Victor plant, consolidating its manufacturing operations elsewhere in New Jersey. In 1997, Lukens Steel was purchased by Bethlehem Steel, which immediately thereafter closed its Pottstown operations and sold Lukens to Mittal Steel. By 2000, an additional 200,000 manufacturing jobs were lost in Philadelphia, and by 2007 the total number of manufacturing jobs left was just over twenty-eight thousand. The majority of the remaining jobs were small shop machine production and finishing for local construction and fabrication firms.

The Philadelphia region was home to numerous machining and custom manufacturing and finishing operations that contributed greatly to the development of the United States and shaped the region as a home for high quality goods. Factors including high wage costs, consolidation, and foreign competition undermined urban operations and the number of regional machining employees. However, machining continued to be an element of the regional economy in suburban locales into the twenty-first century.

Robert F. Smith is assistant dean of humanities and social sciences at Northampton Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University