Poverty

By Paul A. Jargowsky, Christopher A. Wheeler, and Howard Gillette Jr. | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Urban areas in the United States have always attracted destitute persons, including immigrants and internal migrants fleeing even worse poverty and harsher conditions elsewhere. Philadelphia and its environs were no exception, having had a reputation as “the best poor man’s country” reaching as far back as the city’s founding in 1682. Despite the area’s vibrant economy and opportunities for social mobility, however, poverty remained very much a part of its history, even as both the nature and extent of the problem shifted over time.

Assistance for the poor in early Philadelphia was shaped by the tenets of English Poor Law and administered by churches and private organizations, particularly the Quaker Society of Friends, which in 1685 found itself “greatly burthened and oppressed by the increase of the poor.” Responsibility for the poor depended on their origin and condition. Indigent persons deemed able to work were viewed as unworthy of assistance and were imprisoned, whipped, or turned away. Widows, orphans, and invalids received aid, but only if they could not rely on relatives, friends, or other parties deemed to have responsibility for them. Children were often removed from destitute families and placed in apprenticeships.

Pennsylvania was an early leader in developing legislation to provide and regulate public support for the poor. The Pennsylvania Poor Law of 1705 authorized counties to establish overseers of the poor, who could collect taxes for poor relief, and prison workhouses for “felons, thieves, vagrants, and loose and idle persons.” The stigma and harshness of workhouses provided an effective deterrent to seeking public relief. Subsequent laws limited immigrants except for those of unquestionable health, established strict residency requirements for public aid, and allowed Philadelphia to expel vagabonds and paupers from other colonies. The Poor Law of 1771, passed again in substantially the same form in 1778 after statehood, reaffirmed residency requirements (“law of settlement”) and the primary responsibility of grandparents, parents, and children for the care of poor family members.

Uncertain Employment

Working was no guarantee of escaping poverty. Employment was seasonal and subject to economic gyrations. In years that the Delaware River froze in the winter, many were thrown out of work. Those who could not support themselves through market employment or who had debts they could not pay would often be auctioned off as indentured servants, a condition that in practice was little better than slavery, the chief difference being that it was not permanent. Indentured servants could be assigned or leased by their master, could be beaten or whipped for punishment, and needed their master’s permission to quit, marry, or have children. Indentured servitude flourished in Pennsylvania and persisted until the 1830s.

An influx of immigrants in the 1750s and armed conflict—most notably the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763)—boosted the number of poor and forced additional measures to manage the consequences. In Philadelphia, the number of asylums for the poor expanded. Confirming a shift in attitude toward blaming poverty on personal failure rather than the economy, those who turned to institutions for relief faced increasingly unappetizing work requirements. However, such measures did nothing to reduce the number in need. According to figures compiled by historian Gary Nash, the city’s poor rose from 3 percent of the taxable population in the 1720s and 1730s to between 5 and 6 percent by 1759. By the time of the Revolution, one in four free men in Philadelphia were living in poverty.

Immigrants could be counted among the poorest of area residents. To combat their hardships, they formed mutual aid societies, starting with the Welsh Society in 1729. The German Society of Pennsylvania, formed to protect German immigrants who traveled to the colony as indentured servants, followed in 1764. The Hibernian Society and the French Benevolent Society were among other such groups formed for similar purposes.

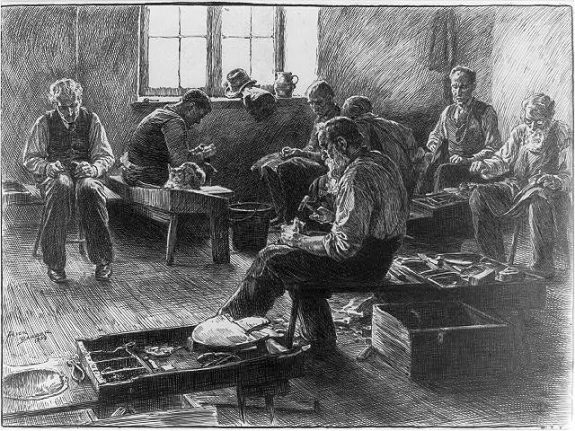

Although the Revolution bolstered Philadelphia’s status as the nation’s richest city by boosting the market economy, prosperity was not widely shared. As agriculture commercialized and manufacturing intensified at accelerated rates inside and outside the city limits, wage laborers endured extended periods of unemployment and hardship. Winter weather cut off many occupations, leaving those who did not plan sufficiently well ahead dependent on a growing number of charitable institutions in the city and surrounding hinterland. As the largest occupational group in Philadelphia, mariners faced particular hardship at the bottom of the income scale together with laborers, but even lower sorts of artisans, notably shoemakers and tailors, struggled to sustain their households. Women, whether living independently or with a husband, were often compelled to work in occupations that did not exclude them where they earned half the wages of men at best.

Crowding on the Fringe

In the first part of the nineteenth century, when pedestrian traffic predominated, the most desirable housing remained at the urban core, close to primary sources of employment. Those lacking the financial resources to buy or rent preferred housing were compelled to find marginal accommodations in courts, lanes, and alleys in the central city or in built-up suburbs immediately adjacent to the city limits–Southwark and Moyamensing to the south and Kensington, Northern Liberties, and Spring Garden to the north—where crowding and inadequate services combined to tarnish their presence. A surge of Irish and German immigrants joining native-born workers in these areas roused concern among Philadelphia’s ruling elite as rising budgets for poor relief failed to reverse the presence of widescale economic distress. Seeking first to impose oversight through the moral suasion of temperance campaigns, Philadelphia’s leadership ultimately imposed administrative control, first by extending the area’s newly formed professional police force to the suburbs and, shortly thereafter in 1854, consolidating all of Philadelphia County with the city. What had once been an effort to assure the deference of the lower classes to those of higher wealth through the assertion of status and position now materialized in new means of administrative control.

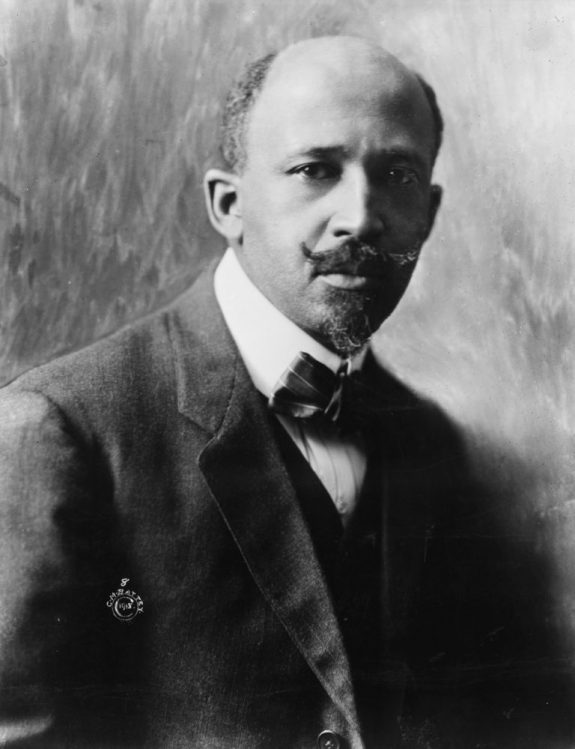

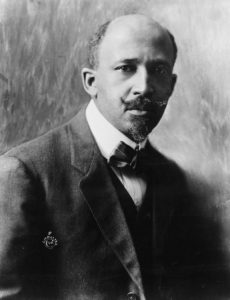

Increasingly marginally poor neighborhoods were associated with immigrants, with Germans congregating first in the northern precincts, while Irish concentrated in the area’s least desirable locations at the city’s edges: Moyamensing, Southwark, and Grays Ferry. By the end of the nineteenth century, Russian Jews and Italians joined earlier streams of poor immigrants hoping to gain an economic foothold in the region’s robust industrial economy. Mixing in the precincts south of the central city, these newcomers settled near the growing presence of African Americans—some eighty-five thousand in total by 1910—a great number of whom were themselves poor migrants from the South. As the competition for jobs intensified, thereby depressing wages, African Americans too had to settle for inferior housing as they crowded into “blind alleys and dark holes,” as the sociologist W. E. B. DuBois (1868-1963) described them in his groundbreaking The Philadelphia Negro (1899), where they filled “trinities,” tiny houses “with three rooms one above the other, small, poorly lighted, and poorly ventilated.” According to DuBois, fully 90 percent of the black families he studied in the city’s Seventh Ward fell below the line set by what he described as the “minimum adequacy budget.” Wary of established institutional forms of relief, he reported, African Americans devised their own network of mutual benefit societies to get by.

Echoing earlier responses to people marginalized in the modern economy, these clusters of poor, but largely working people prompted calls for reform—in schools promoting Americanization and in homes through instruction brought by settlement and later social workers. Reflecting a growing confidence among reformers that environmental intervention constituted an effective means of lifting the poor out of poverty, Progressive era reformers sought to improve both housing and adjacent infrastructure in neighborhoods where the poor congregated in unsanitary and often physically dangerous conditions. Their research, often buttressed by dramatic photographic evidence, roused public conscience to induce both new philanthropic and government investments in areas considered slums.

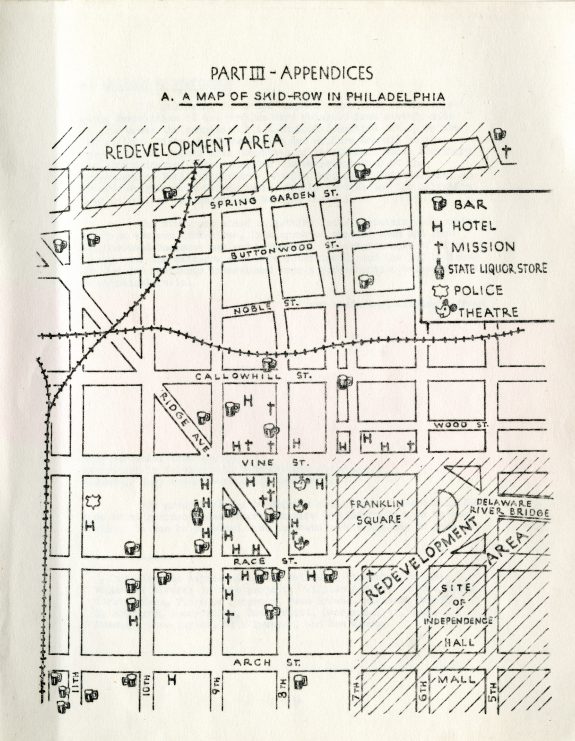

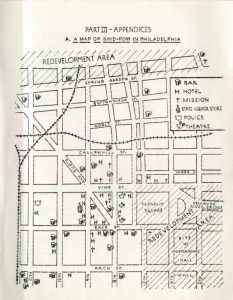

As streetcar and train service provided access to better living conditions beyond the core city, once desirable residential areas downtown declined, giving way to the city’s first tenderloin district and a skid row stretching east to the Delaware River, an area where poor, homeless, and transient men congregated amid the missions, saloons, and cheap establishments that catered to them.

African American Migration

African American migration to the city accelerated in the first part of the twentieth century, driven by conditions in the South and the prospect of employment spurred by World War I. From less than forty thousand in 1890, the city’s black population climbed to 134,229 by 1920. With the advent of peace, these newcomers were dismissed from wartime jobs and, lacking access to either manufacturing employment or housing in the outer residential neighborhoods, sought accommodations in locations once dominated by immigrant workers. This was especially true in the area just north of the central city. By 1930 some seventy-eight thousand African Americans concentrated in the lower part of North Philadelphia, prompting its reputation over time as a location of high poverty and associated crime as “the jungle.”

The Great Depression brought hardship to all area residents, but in Philadelphia, where unemployment among whites reached 11.5 percent in 1933, the situation was even worse for blacks and immigrants, who suffered rates of unemployment of 16.2 and 19.1 percent respectively. Ultimately, 60 percent of African Americans were eligible for poor relief or public assistance, and 51 percent of black renters lived in substandard housing compared to 14 percent of white renters. New Deal initiatives, providing public housing and employment, ameliorated some aspects of poverty among African Americans but did not substantially close the gap with whites.

Despite the boost World War II gave to employment for blacks as well as whites, the loss of manufacturing jobs in the region after the war hit African Americans, whose employment was concentrated in industry and service, especially hard. As Philadelphia lost ninety thousand jobs between 1952 and 1962, black unemployment rose to 11 percent, compared to only 5 percent among whites. As redlining, racial steering, and other forms of housing discrimination kept the bulk of the region’s African American population deeply segregated from whites, geographic disparities widened. A survey of some of the city’s poorest African American neighborhoods reported 37 percent of the labor force jobless and 42 percent employed only irregularly as domestics, service workers, and common laborers.

The civil rights movement, race riots, and the War on Poverty called attention to the problems of poverty, particularly with respect to the nation’s urban cores. Philadelphia’s political elite responded with a variety of programs, much in line with the anti-poverty spirit of the time encouraged by the Johnson administration’s Great Society initiatives. To tackle the growing poverty problem, the federally-funded Model Cities program targeted Lower North Philadelphia with special health, education, transportation, and employment programs. In addition, the program focused targeted investments on the neighborhood’s housing stock while constructing large amounts of public housing. The overwhelming concentration of subsidized housing in impoverished neighborhoods nonetheless effectively concentrated the region’s chronically poor in contained, high-poverty areas. Such programs also failed to stimulate private sector investment and reverse the abandonment and neglect afflicting Philadelphia’s poorest neighborhoods.

Flawed Anti-Poverty Agencies

Supplementing the Model Cities program, Philadelphia’s federally-funded anti-poverty Community Action Agency was among the first in the nation to be created. However, such city anti-poverty agencies were wracked with internal conflict and power struggles over the composition of the governing boards. These programs did not actively engage the poor themselves in planning and implementation, and the heavy involvement of local political elites transformed it into a form of political patronage. For example, Philadelphia Mayor James Tate (1910-83) offered just enough participation and control for African American community leaders to control some patronage, but not substantially affect the distribution of political power in the city. More importantly, none of these programs were designed to or capable of addressing the fundamental dynamic of rampant suburbanization that was undermining the economic and fiscal conditions of the region’s central cities. Moreover, funding for these programs, inadequate to begin with, fell sharply in the poor economic conditions of the 1970s. In the process, anti-poverty efforts became more localized with the emergence of community development corporations in Philadelphia and Camden. These community-based nonprofit entities did their best to attack neighborhood poverty by providing vital social and human services while promoting locally-based business development, job creation, and housing rehabilitation and development activities.

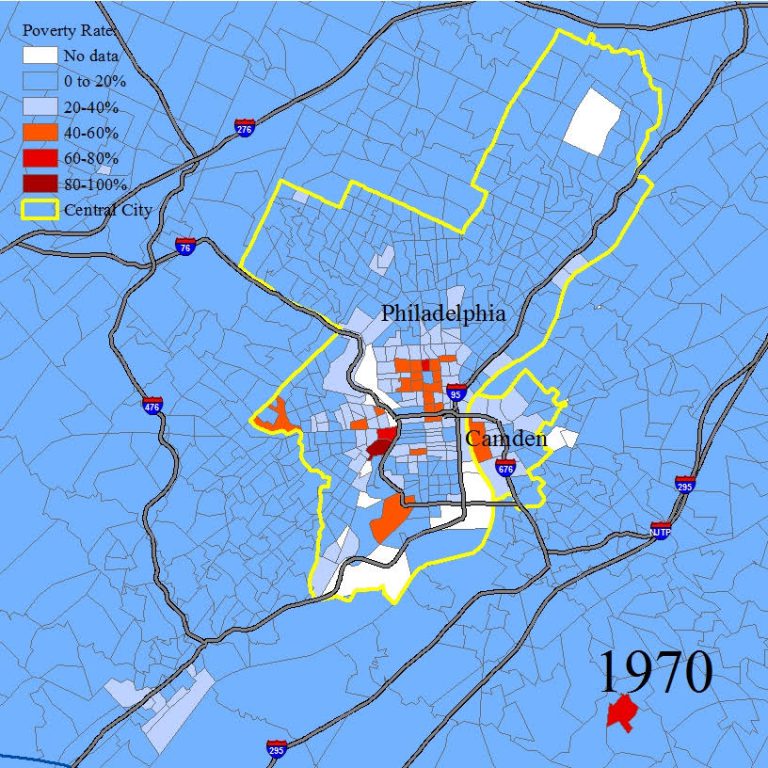

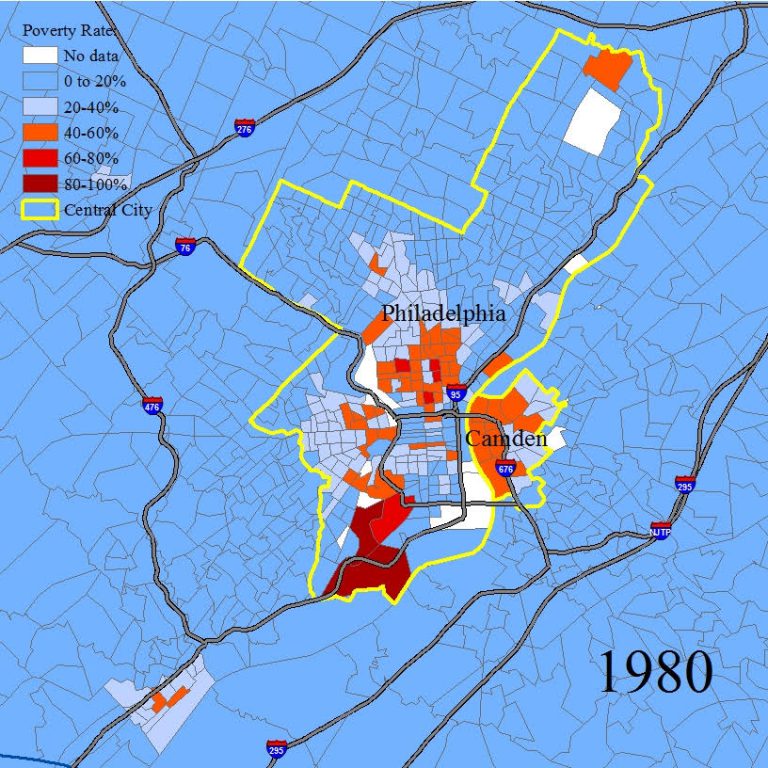

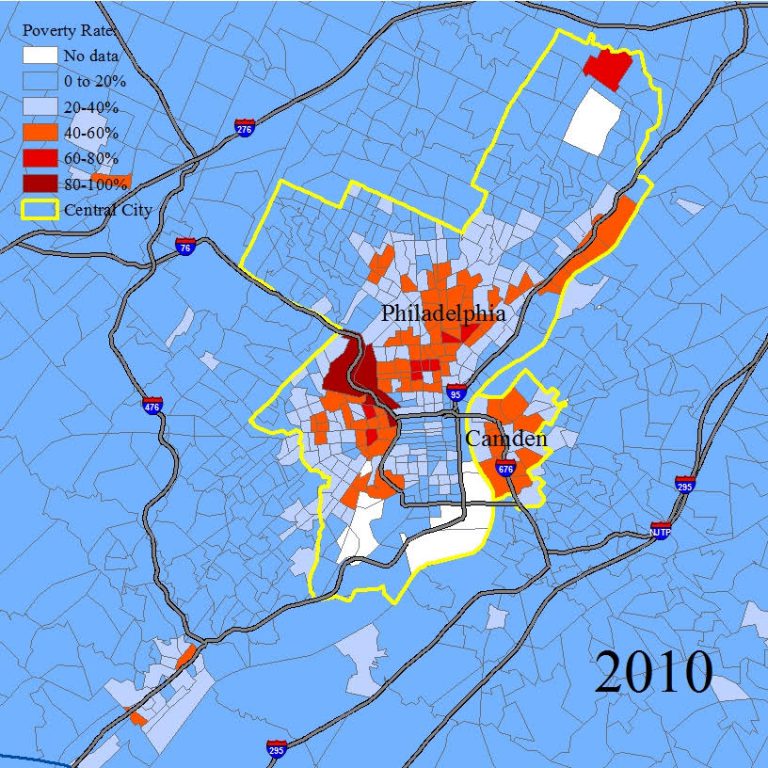

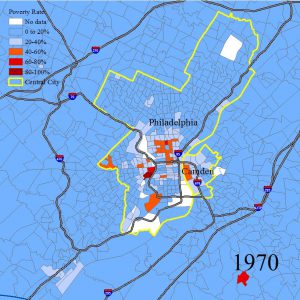

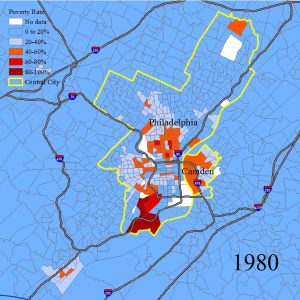

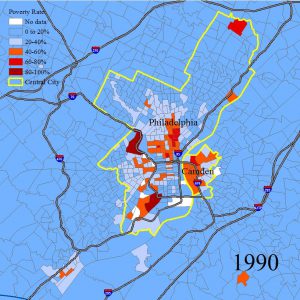

The manufacturing share of the eight-county region’s jobs continued to decline, falling from one third in 1970 to one in ten by 2010; over that period, over 340,000 manufacturing jobs were lost. This economic transformation had profound implications on the concentration of poverty across the Philadelphia region. As poverty and crime escalated in the city, those who had the means joined the migration from the city to new suburban areas with the promise of better housing and a higher standard of living. Suburbs were built at such a fast pace that their growth was essentially cannibalistic, leading the population of the urban core to decline even as the region continued to grow. Through exclusionary zoning and other restrictive land use policies, these new suburbs drew the most affluent families, changing the city by subtraction and leaving a higher share of its population in poverty.

Poverty in the region was not limited to Philadelphia proper. Some racially diverse working-class and middle-class industrial towns, such as Camden, Norristown, and Chester, quickly became centers of racially concentrated poverty. Across the Delaware River, Camden, New Jersey, a shipping and manufacturing center since the nineteenth century with a diverse industrial base, experienced rapid economic decline in the decades immediately following World War II. The city’s traditional population, largely European immigrants and their descendants, moved to fast-growing suburban areas as African American and Hispanic populations moved in, just as the city’s manufacturing jobs were disappearing. The city’s poverty rate rose from 23.5 percent in 1970 to 42.6 percent in 2013 while the inflation-adjusted median household income dropped by over a quarter from $29,793 in 1980 to $22,043 in 2013. Unemployment in the city in 2013 stood at 18.7 percent, nearly two times the regional rate.

Norristown, a center for the textile industry since the nineteenth century, suffered greatly from the decline of industry in the nation’s older urban centers. The borough’s poverty rate rose from approximately 9 percent in 1970 to 19.3 percent in 2010, while unemployment rose from 3.3 percent to 11.3 percent. Norristown experienced a sharp decline in its white population, replaced largely with African Americans and Hispanics.

New Arrivals in a Time of Decline

Chester, long a center for shipbuilding and auto manufacturing, lost thousands of jobs as industries moved to other regions and overseas. Due to its status as a hub for manufacturing jobs, Chester attracted a large influx of African Americans, rising to 45.2 percent black in 1970 and over 76.0 percent in 2010. Unfortunately, many arrived just as the major industries were in rapid decline. Chester’s poverty rate climbed from 19.7 percent in 1970 to 31.4 percent in 2010. In addition, a few smaller boroughs such as West Chester in Chester County and Paulsboro in Gloucester County also developed concentrations of poverty, with 2010 poverty rates of 25.5 and 29.2 percent respectively.

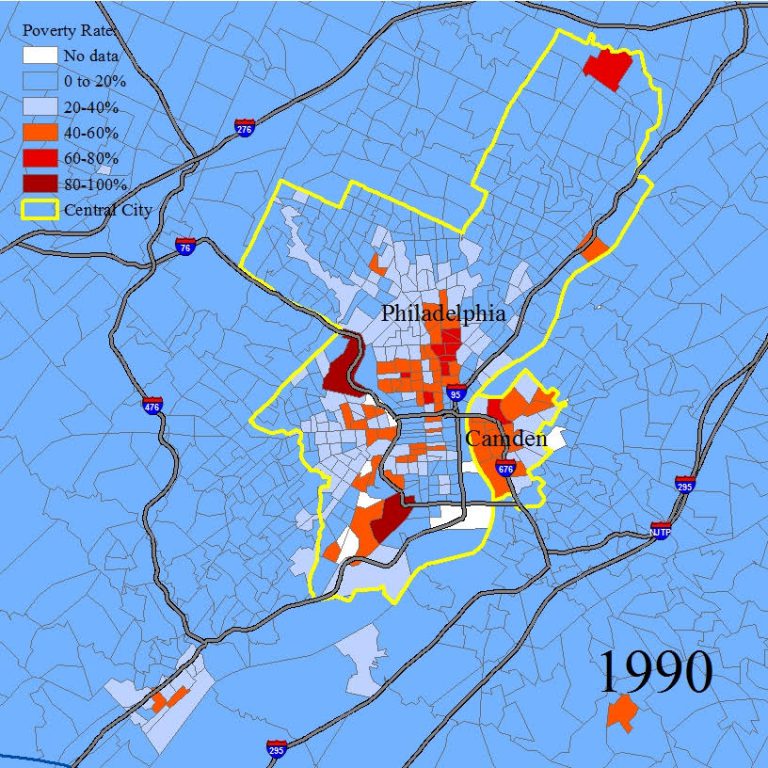

Another factor that began to contribute to poverty in Philadelphia was the rapid growth in the city’s Hispanic population, rising from approximately 43,000 in 1970 to 174,000 in 1990 and 414,000 in 2010. Hispanic newcomers, primarily relocating from Puerto Rico, were disproportionately poor and settled primarily in the neighborhoods east of Broad Street, from Kensington at the south end to Olney at the north end. By the early years of the twenty-first century the poverty rate of Hispanics in Philadelphia had reached 44 percent. Hispanics also settled in neighborhoods in the lower Northeast and in the northern and eastern portions of Camden.

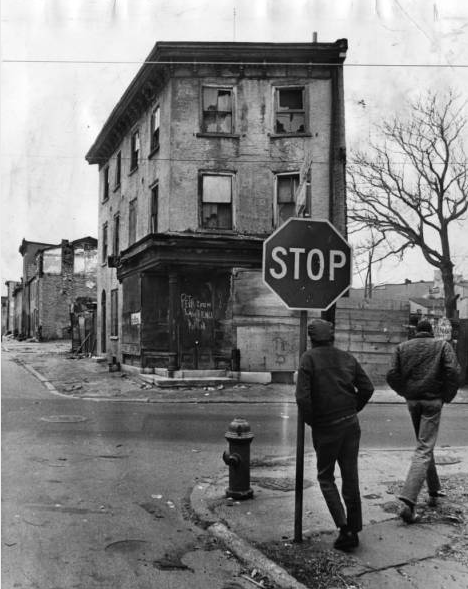

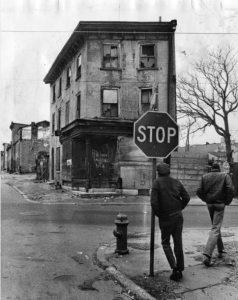

By 1980, poverty had become far deeper and more widespread in North Philadelphia, West Philadelphia, and Camden. Continued “white flight” and population growth in the suburbs meant that the poor became increasingly segregated in neighborhoods with low concentrations of the non-poor, especially within Philadelphia. Housing conditions in these neighborhoods continued to deteriorate, leaving an abundance of abandoned and dilapidated housing structures. High poverty neighborhoods were characterized by drugs and violence, a heightened police presence, and a proliferation of arrests and incarceration.

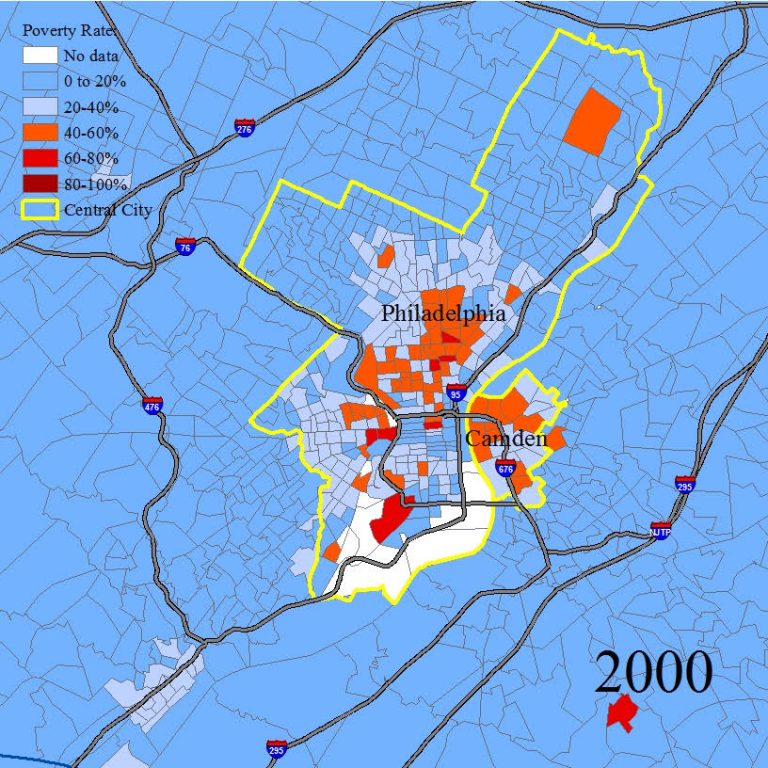

In the 1990s, buoyed by a strong national economy and low unemployment, the percentage of the poor living in concentrated poverty neighborhoods dropped sharply. Although African Americans still comprised the largest share of the region’s poor in 2010, their share steadily dropped since 1990, due in large part to population growth from other racial and ethnic minority groups. Moreover, migrants from other metropolitan areas began to strongly contribute to the persistence of poverty in the region. Those who had lived in another metropolitan area five years earlier increased from approximately 18 percent of the poor in 1980 to 35 percent in 1990. Most of these poor newcomers were non-Hispanic whites and African Americans.

Recession Undermines Gains of the 1990s

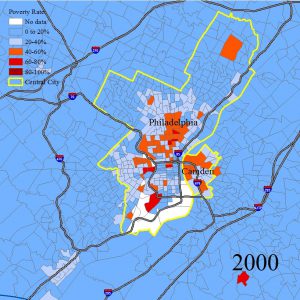

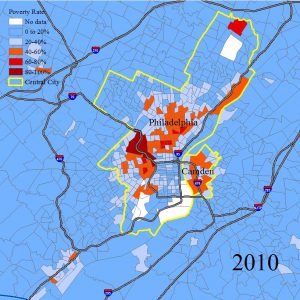

In the 2000s, slower economic growth and the Great Recession beginning in 2008 reversed the gains of the 1990s and boosted the metropolitan region’s poverty rate. While the percentage of the region’s poor living in high-poverty neighborhoods had been steadily dropping from 25.3 percent in 1970 to 17.9 percent in 2000, by 2010 a remarkable 7.4 percentage point increase brought the rate back to the 1970 level. Concentrated poverty within Philadelphia spread beyond persistently impoverished neighborhoods to areas that had been bastions of the city’s middle and working classes. For example, concentrated poverty emerged in such neighborhoods as Haddington in West Philadelphia, Feltonville in the Lower Northeast, and Germantown in the Northwest.

Due to deterioration of older suburbs and displacement caused by gentrification, poverty became more prevalent in the suburbs. By 2013, the percent of the Philadelphia metropolitan area’s poor who lived in the suburbs had reached 50 percent, up from 44 percent in 2000. Poverty rose sharply in the region’s older inner ring suburbs such as Wyncote in Montgomery County, Darby in Delaware County, and Woodlynne in Camden County, New Jersey.

By 2010, the ranks of the Hispanic poor had become much more diverse. Puerto Ricans’ share of the Hispanic poor had fallen to 57.8 percent, as Mexican and other Latin American immigrants formed an increasing share of the Hispanic poor. Mexicans accounted for 7.4 percent of the region’s Hispanic poor in 1980. By 2010 they accounted for 17.4 percent. That year, 60 percent of the Mexican poor were born outside the United States. A gradual increase in the immigrant poor contributed to the persistence of poverty in the region.

The sources of poverty in Greater Philadelphia and the policies to address it evolved over time, yet it remained a persistent problem. The collapse of the manufacturing economy in particular set in place a series of changes that served to stratify the region. As social and economic conditions in the city declined and jobs became less tied to central workplaces, suburban sprawl facilitated white and middle-class flight. With no effective control over suburban growth, either in terms of pace or racial and economic exclusivity, the modern metropolitan area created vast disparities in neighborhood conditions and proximity to economic opportunities that highly disadvantaged the region’s minority populations. Gentrification, as it accelerated in parts of Philadelphia in the early twenty-first century and the increasing presence of poor residents in the older suburbs were new wrinkles in a persistent pattern, but the metropolitan area remained highly segregated by race and social class.

Paul A. Jargowsky is Professor of Public Policy and Director of the Center for Urban Research and Education at Rutgers University in Camden, New Jersey. He is the author of Poverty and Place: Ghettos, Barrios, and The American City and The Architecture of Segregation.

Christopher A. Wheeler is a research economist and manager of data analysis at the New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. He is the author of a 2014 study for the Senator Walter Rand Institute for Public Affairs at Rutgers-Camden, Poverty Dynamics in South Jersey: Trends and Determinants, 1970–2012.

Howard Gillette is Professor of History Emeritus at Rutgers-Camden and co-editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Inside the clinic that treats Germantown's 'working poor' (WHYY, May 8, 2013)

- UPenn researcher: Place and poverty influence HIV risk (WHYY, May 19, 2014)

- Poverty growing for Delaware children (WHYY, April 1, 2015)

- Report: 2.8 million in NJ living in poverty (WHYY, November 15, 2015)

- Lawmakers ponder how to help 2.8 million living in poverty in New Jersey (WHYY, February 1, 2016)

- Concentrated poverty grows in Pennsylvania (WHYY, April 1, 2016)

- Taking on the challenges of poverty in Philadelphia (WHYY, May 18, 2016)

- Philly rise from deep poverty depends on broad political, societal changes (WHYY, July 26, 2016)

- Why is poverty increasing in Northeast Philly? (Philadelphia Inquirer via WHYY, September 21, 2019)

Links

- History of the Chester County Poorhouse

- Fifty Years Before the War on Poverty (Philly History Blog)

- The Rise of Neighborhood Noir (Philly History Blog)

- Hypersegregation + Redlining + Time = Persistent Decline (Philly History Blog)

- Is "Gentrification" Going the way of "Slum"? (Philly History Blog)

- Kensington Blues Puts A Human Face On A Lost Population (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Testing The Gentrification Narrative At Temple University (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Blum Come Down (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Poverty in Philadelphia (Pew Charitable Trusts)

- Broke in Philly Collaborative Reporting Project