Trees

Essay

Trees have been culturally, environmentally, and symbolically significant to the Philadelphia region since the city’s founding. They were believed to improve public health, they beautified and refined city streets, parks, and other green spaces, and several were revered as living memorials to past historical events. Trees also faced their fair share of destruction during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as unregulated agricultural clear-cutting, competitive markets for fuel and timber, growing industry, and expanding population eliminated many of the region’s forests. Beginning in the late nineteenth century and continuing into the twenty-first century, local, regional, and state organizations have collaborated to increase the tree canopy cover in the Greater Philadelphia area.

Pennsylvania—Latin for “Penn’s Woods”—is uniquely positioned as a space where northern and southern tree species overlap, although Appalachia Oak Forest covers the majority of the state, including around Philadelphia, southern New Jersey, and Delaware. This forest type consists primarily of oaks with black birch, black gum, red maple, hickories, tulip tree, and white pine. William Penn (1644-1718) boasted of the arboreal production of the region—which included present-day New Jersey and Delaware—a few years after King Charles II (1630-1685) presented him with the Pennsylvania colony in 1681: “The trees of most note are the black walnut, cedar, cypress, chestnut, poplar, gumwood, hickory, sassafras, ash, beech; and oak of divers sorts, as red, white, and black, Spanish, chestnut, and swamp.”

Planning a “Greene Country Town”

By the time Penn arrived in North America, however, Native Americans had already dramatically altered the region’s forests. The Lenni Lenape used fire to manage forests, clear land for agriculture, and burn underbrush to encourage the growth of young plants that attracted deer and other small game. Native Americans depended heavily on wood, bark, and vegetable fibers to construct houses and other material goods. When villages exhausted forests after a few decades, communities settled in new sites a few miles away and the process began all over again. By the late seventeenth century, however, European disease had decimated the native population and many of their cultivated spaces may have become overgrown.

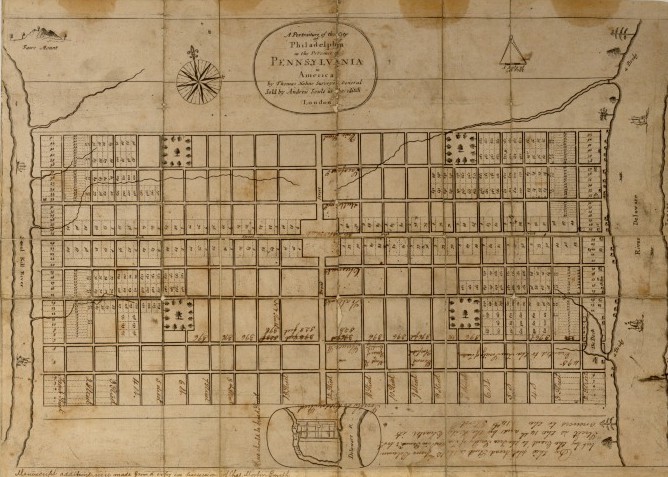

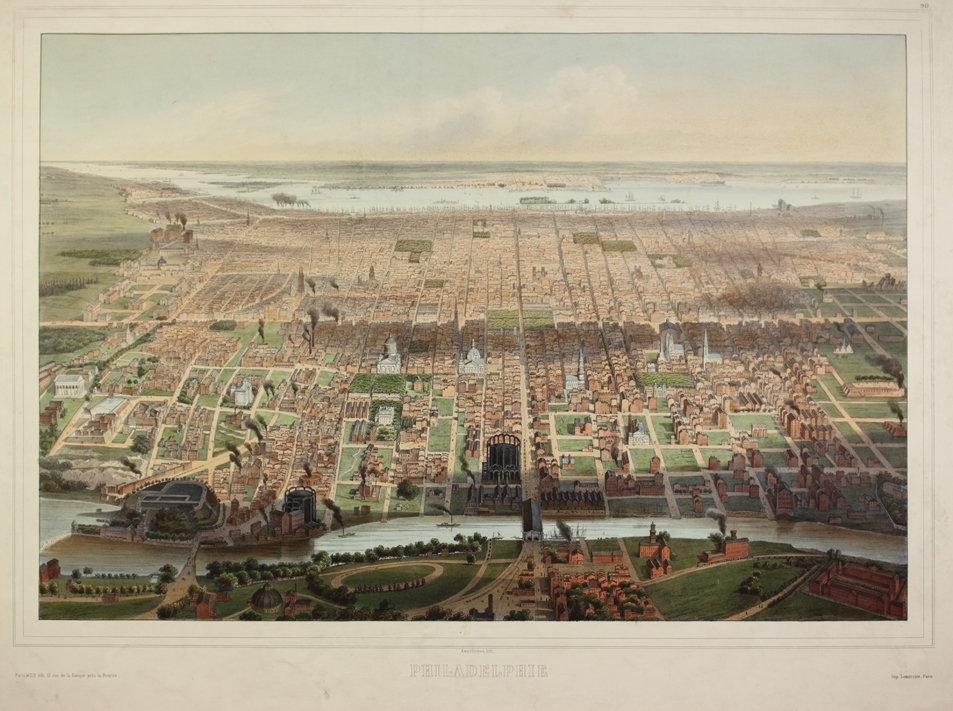

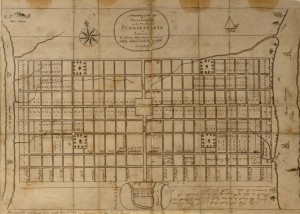

In 1683, when William Penn and surveyor Thomas Holme (1624-95) laid out Philadelphia’s streets in a symmetrical grid, they envisioned trees and green space as important components of the city plan. Penn reserved land for five public squares in different sections of the city and he intended for every house to be surrounded by gardens, orchards, or fields, “that [Philadelphia] may be a greene country town which will never be burnt and always be wholesome.” Inspired by the many types of trees that grew in the region, Penn named the east-west streets of Philadelphia after local varieties: Cedar (now South), Pine, Spruce, Walnut, Chestnut, Mulberry (now Arch), and Sassafras (now Race).

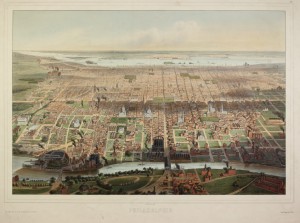

Even though most Philadelphians did not set aside large portions of their land for trees and plants as Penn envisioned, a 1796 map of Philadelphia by John Hills showed trees to be a defining feature of the city after the Revolutionary War. Trees shaded the grounds adjacent to the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall), and wealthy citizens planted them in front of their homes, inspired by the tree-lined promenades of European cities like Paris and Antwerp. Art historian Therese O’Malley has argued that a desire to ornament the new republic motivated an increased interest in landscaping after the Revolution; city trees provided a way to project an aura of refinement and gentility.

Sprucing Up the Squares

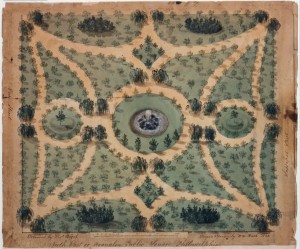

In the 1820s, Philadelphia began rehabilitating Penn’s five original squares, most of which had fallen into disrepair; several were used as trash dumps, potter’s fields, and sites for public hangings. The city attempted to reclaim these spaces through the assignment of commemorative names—Franklin, Washington, Logan, and Rittenhouse—and landscaping. Only the plan for Franklin Square, submitted by the sculptor and city councilman William Rush (1756-1833) and painter Thomas Birch (1779-1851), survived as a record of these projects. The design for this northeastern square depicts an ordered, picturesque view of nature. The numerous, evenly spaced trees and symmetrical copses of evergreens and willows exhibit a desire to order and beautify public space and underscore the close association between trees and health in early nineteenth-century medical philosophy. Physician Benjamin Rush attributed declining health and yellow fever outbreaks in Pennsylvania to “the cutting down of wood, [which] tends to render a country sickly.” He recommended planting trees at unhealthy sites to absorb and purify unwholesome air

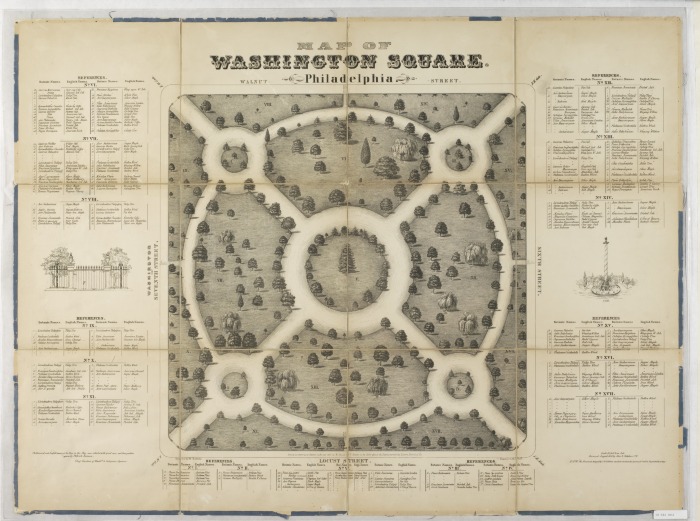

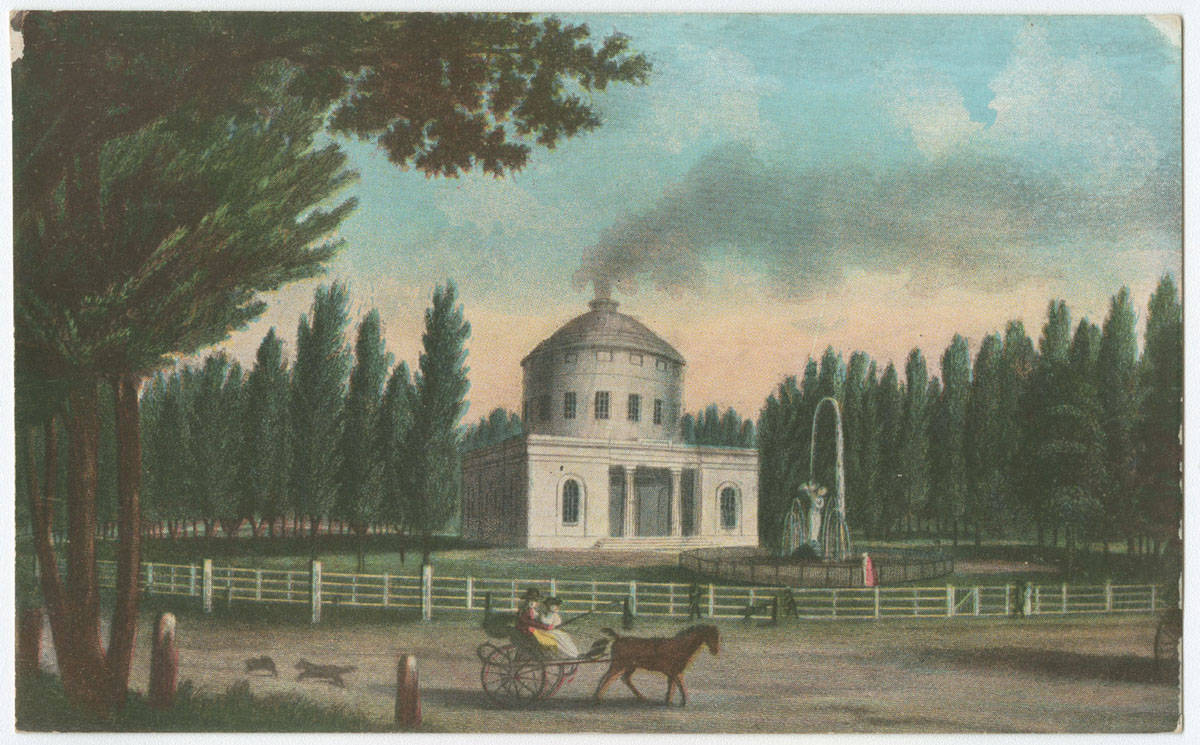

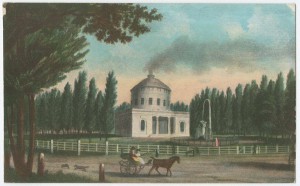

Several squares in Philadelphia became defined by their distinctive trees. Tall Lombardy poplars lined the pathways of Centre Square, the location of a neoclassical Engine House powering the city’s first Waterworks and, later, the site of City Hall. First brought to the United States from Europe in the 1780s by William Hamilton (1745-1813), the proprietor of the Woodlands estate outside the city, Lombardy poplars became extremely popular throughout the Northeast because they quickly grew to great heights and were easily transplanted. Many American cities planted Lombardy poplars after 1799, the year of George Washington’s death, because they were believed to be the first president’s favorite tree. Washington Square served as an arboretum to educate the public about horticulture. By 1831, the square contained fifty varieties of North American and European trees, two of which were introduced by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark from their 1804-06 expedition in the Rocky Mountains.

Select trees in the Philadelphia region were venerated as silent witnesses to a historical and environmental past in the nineteenth century. Paintings, prints, textiles, and fine china celebrated the “Treaty Elm,” under which it was believed William Penn purchased land for Philadelphia from the Lenape in 1683. Images of the respected tree referenced Philadelphia’s creation narrative while also reminding the viewer of the sylvan heritage that contributed to the region’s economic success. A blow to that hallowed heritage occurred when the elm fell in an 1810 storm. The elm’s wood was converted into various artifacts—including trinket boxes and portrait busts of Penn–disseminated throughout the nation and even across the Atlantic Ocean to England. The Treaty Elm, through its destruction, commemoration, and veneration, served as a tangible symbol of the state’s sylvan past, saturated with mythic historical meaning.

Heavy Harvesting

While trees were cultivated in city streets and parks and revered as historical eyewitnesses, they were aggressively harvested in the region’s hinterlands from the eighteenth until the early twentieth century. Wood served as a primary resource for the region. By 1810, approximately two thousand sawmills in Pennsylvania produced nearly seventy-five million feet of sawn lumber. Philadelphia exported or utilized huge quantities of this wood in shipbuilding, housing, construction, tanning, and fuel.

As a result of rapid wood consumption, timber in easy proximity to transportable waterways became scarce by the beginning of the nineteenth century. Large forests of oak, chestnut, pine, and cedar in southwestern New Jersey, directly across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, almost completely disappeared because of agricultural clear-cutting and fuel consumption. One sawmill operator reported in 1821 that the large rafts of sawn lumber floated downstream to the Delaware River wharves north of Vine Street “have decreased [and] they must more & more…the Timber in most places is nearly all cut away.” This deforestation increased by the end of the nineteenth century with the advent of the railroad logging era. Geared logging locomotives allowed the lumber industry to harvest vast, previously inaccessible, acres of forest, and advances in chemistry permitted all types of wood to be treated and distilled into acetate of lime, wood alcohol, wood tar, charcoal, and gases.

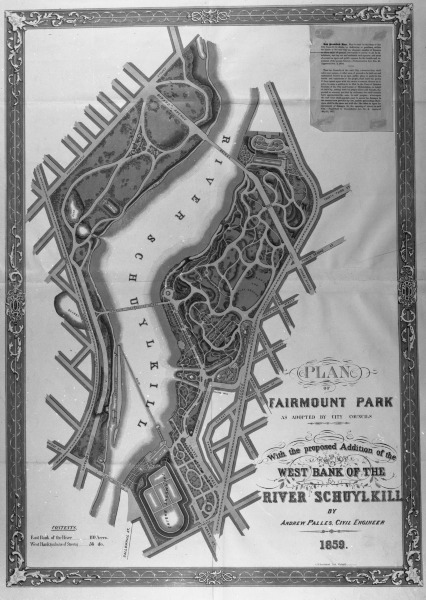

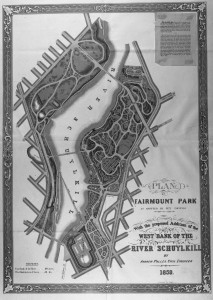

This widespread deforestation alarmed residents of the greater Philadelphia region who understood the importance of trees within their urban, suburban, or rural environments. Throughout the nineteenth century, artists and writers like Thomas Cole, Frederick Church, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry Thoreau promoted a romantic view of forests as spaces of sublime power and mysticism. In the 1860s, George Marsh’s text, Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action, alerted North Americans to the interconnectedness of nature, demonstrating that trees controlled erosion, mediated flooding, and filtered water. As Philadelphia and its surrounding counties developed and industrialized during the nineteenth century, the city began taking steps to preserve wilderness areas in order to protect the upstream sources of its water supply. Philadelphia’s city government purchased land along the Schuylkill River and established Fairmount Park in 1855 to prevent industry from accumulating along the riverbanks and polluting the city’s drinking water. Fairmount Park commissioners preserved the park’s original terrain, with the minor additions of carriage roads and walking paths, noting “the diversified character of the grounds, and the abundance of noble trees and groves give us, at many points, a Park made to our hands.”

Preservation and Planting

By the late nineteenth century, forest education and advocacy campaigns organized by concerned citizens culminated in the establishment of forestry departments and policies at the state and national level. The French botanist François André Michaux (1770-1855)—author of the foundational treatise of American forestry, North American Sylva (1819)—left a legacy of $12,000 to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia to fund a lecture series in silviculture (the science-based management of forests). The resulting Michaux Forestry Lectures, presented from 1877-92, represent an early attempt to educate the general public on forestry concerns. The Pennsylvania Forest Association, founded in Philadelphia in 1886, developed from discussions of forest issues at a local women’s club. Joseph T. Rothrock (1839-1922), a professor of botany at the University of Pennsylvania and frequent Michaux Forestry lecturer, was elected the association’s first president and later became the state’s first commissioner of forestry.

Over the next century, local, state, and national governments assumed responsibility for the planting, cultivation, and preservation of trees in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey. In 1895, a Forestry Commission appointed by the Pennsylvania State Board of Agriculture reported that the amount of forested land in the state had decreased from more than ninety percent to thirty-six percent of the state’s land area, threatening timber supply, water quality, and public health. The Pennsylvania Forestry Commission began purchasing marginal or cutover land abandoned by farmers and timber industries in 1898 in order to encourage forest regrowth and the State Department of Forestry continued these activities after its establishment in 1901. New Jersey established a Forest, Park, and Reservation Commission in 1905, and Delaware introduced a State Board of Forestry in 1909 to monitor and preserve their own forests. By 1936, nearly 179 million seedlings raised in state-funded nurseries had been planted in state forests, along streets and highways, and on private land in Pennsylvania. The early twentieth century also saw the establishment of several local, publicly accessible arboretums—including Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania and Tyler Arboretum in Media—to preserve and study local trees and species from all over world.

In 2011, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society partnered with thirteen counties in southeastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware in a “Plant One Million” campaign to restore the tree canopy cover of the region to thirty percent, replacing trees lost to development. The Parks and Recreation Department additionally introduced the TreePhilly initiative in 2012 to provide free yard and street trees and facilitate maintenance workshops for urban communities. Tree canopy covered twenty percent of total land in Philadelphia in 2012, a four percent increase from 2008, according to a study by the University of Vermont Spatial Analysis in partnership with the United States Forest Service. Valued for their role in improving air and water quality, blocking noise pollution, providing shade, and reducing the “urban heat island effect,” trees became more and more visible within the diverse landscape of the greater Philadelphia region.

Laura Turner Igoe is a Ph.D. Candidate in Art History at Temple University. Her dissertation, entitled “The Opulent City and the Sylvan State: Art and Environmental Embodiment in Early National Philadelphia,” considers how artists and architects used the body as a framework to visualize, comprehend, and reform the city’s rapidly changing urban ecology after the Revolutionary War. Her research has received support from the Philadelphia Area Center for the History of Science, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, the Henry Luce Foundation and the American Council of Learned Societies. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Trees still blooming at Morris Arboretum's cherry blossom festival (WHYY, April 14, 2014)

- Wood artists salvage beauty from destruction at Bartram's Garden (WHYY, May 3, 2014)

- Philly mapped street trees for smarter maintenance (WHYY, July 29, 2016)

- Philadelphia just received the 'largest investment' in its urban forest in decades (WHYY, September 19, 2023)