Urban Renewal

Essay

Urban renewal was a nationwide program aimed at maintaining the dominant position of central cities in the face of the urban crisis and suburban growth that marked the decades following World War II. Philadelphia was a leader in this revitalization practice, reserving more federal urban renewal grant funding ($209 million), by the end of 1965, than anywhere else in the country besides New York City. The city also stood out for its distinctive “Philadelphia Approach,” which operated at a smaller scale and in a less physically destructive manner than that of the typical American city. Yet, just as across the country, urban renewal in Philadelphia yielded mixed results that incited controversy.

Federal legislation critically enabled the public-private partnerships behind urban renewal’s implementation, while local actors tailored these policies’ effects in practice. Title I of the Housing Act of 1949 provided loans and two-thirds federal grants to support the acquisition of land and clearance of the areas designated as blighted. Private developers would then redevelop these properties. They did so initially for new housing. Following passage of the Housing Act of 1954, however, they pursued other reuses as well, including shopping, industry, and offices. The Housing Act of 1954 also expanded federal funding to support housing rehabilitation in addition to site clearance.

Philadelphia’s Central Urban Renewal Area (CURA) Study, of 1956, shifted the city towards rehabilitation by focusing timely investments of limited funding on “conservable”—rather than “worst-first”—areas of the city. Even so, the national program—epitomized by Robert Moses (1888-1981) in New York City—emphasized top-down approaches to renewal that generally prioritized demolition of buildings and displacement of population in order to make way for new, modern development. Advocates of the program hoped, variously, to replace dilapidated housing, modernize the city and its relationship to automobiles and highways, strengthen the urban tax base by upgrading the uses of central city land, and create appealing alternatives to the suburbs in order to stem the flight of industry, commerce, and middle- and upper-class residents.

Like hundreds of cities across the country, Philadelphia actively embraced urban renewal. By 1952, it had designated sixteen redevelopment areas, most of them centrally located. Over time, these numbers only increased. In the mixed success of its big downtown office and commercial developments, as well as its creation of many large housing projects, Philadelphia’s experience was quite representative of the national story. But, under the leadership of Edmund Bacon (1910-2005), executive director of the Planning Commission, and William Rafsky (1919-2001), who as the city’s housing director and development director (among other roles) was the driving force behind the CURA policy, Philadelphia also distinguished itself in several ways. It relied more heavily on alternatives to wholesale clearance, “curing slums with penicillin, not surgery,” as Architectural Forum famously put it. The result was a pedestrian-oriented approach to urban renewal that also valued neighborhood conservation. Housing was a particular priority in Philadelphia, and the city built upon its row house past to emphasize low-rise development, not just high-rise construction—for multiple income levels. Finally, the city responded directly to deindustrialization both by rehabilitating existing facilities and by planning for new industrial parks in less central urban locations. Thus, the Philadelphia Approach to urban renewal was both typical and distinctive.

Early Urban Renewal

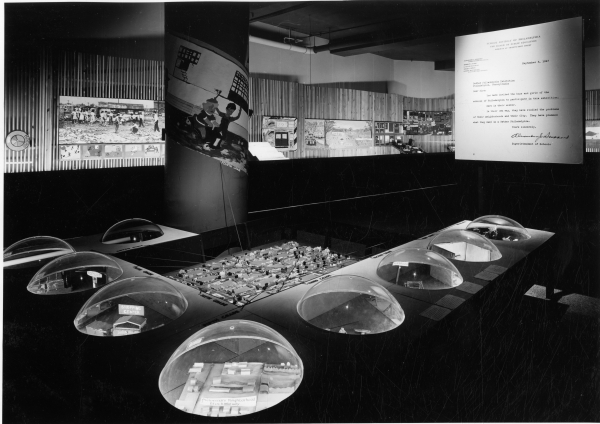

Philadelphia’s urban renewal era began even before passage of the key federal acts. Following Pennsylvania’s 1945 enabling law, the city established its redevelopment authority in 1946. The Better Philadelphia Exhibition of 1947, held at Gimbels department store, deployed photographs, maps, movies, a diorama, a life-size model of a rehabilitated row house, and a vast 14-by-40 foot scale model to showcase Edmund Bacon and architect Oskar Stonorov’s (1905-1970) vision for the city. The reform movement used the exhibition as a key tool for promoting their planning-oriented vision for the city. The event set the stage for the 1951 victory of Mayor Joseph S. Clark, Jr. (1901-1990) who, followed by Mayor Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974), supplied political leadership behind urban renewal. In tandem, the 1948 formation of the Greater Philadelphia Movement, a civic group of key business leaders, provided private sector support for urban renewal in the city.

Philadelphia’s first urban renewal project was in East Poplar, a neighborhood located in lower North Philadelphia. As in most early renewal projects, planners selected East Poplar due to its significant levels of blight. In eradicating that blight, the city also attempted to provide housing affordable to displaced residents. Although the city supplemented Title I funds to reduce rents in the Towne Center development, not everyone could afford those rates. New slums formed around the perimeter to house lower-income displacees. A venture between the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority and American Friends’ Service Committee turned to cooperative rehabilitation, but again yielded rents too high for many of the original residents. The problem of displacement and housing affordability would persist throughout the era of urban renewal.

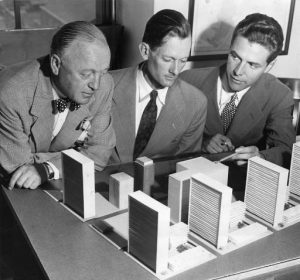

The more visible Penn Center project was the city’s first major downtown redevelopment endeavor. It began in 1952, when the Pennsylvania Railroad vacated its Broad Street station and the adjacent blocks of elevated tracks. This expanse of infrastructure, known as the “Chinese Wall,” had divided this central city location and left dilapidated conditions along its periphery. Bacon hoped to see the large site developed as a single entity that could knit the area back together and serve as a welcoming civic and commercial center. He supported a design by architect Vincent Kling (1916-2003) modeled on New York City’s Rockefeller Center. A street-level pedestrian mall, with parking garages at its ends, would connect three new elevated office towers and offer sweeping sight lines to City Hall. Below ground, a pedestrian concourse would include stores, restaurants, a skating rink, an open central plaza, and connections to rail. Yet the city lacked the funds necessary to purchase the privately owned site and control the design. Instead, the railroad company selected private developers who pared down the original concept for cost-saving purposes, yielding a built project that fell short of its grand urban design expectations.

Market East

Market East was another major downtown project. There, planners sought to realize the commercial redevelopment that was largely unmet at Penn Center. In 1958, the Planning Commission introduced a proposal for a complex of buildings, multimodal transportation access, open-air pedestrian circulation, and office space above that competed with the scale of suburban shopping. Architects Bower & Fradley designed the enclosed, climate-controlled mall. The combined efforts of the Redevelopment Authority, the national retail developer Rouse Company, and the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) led to the opening of The Gallery at Market East in 1977. It included two anchor stores, 122 shops and restaurants, a parking garage, and approval for a new commuter rail tunnel to connect with existing transportation lines. Gallery II, a companion project located one block east, opened in 1983. It included another anchor store, smaller-scale shops, an underground rail station, and office space. Although the malls were originally aimed at drawing suburban shoppers back downtown, it was urban patrons who largely fueled their impressive early sales levels.

While Penn Center and Market East aimed to revitalize downtown commerce, other projects strove to eliminate commercial uses from residential areas. The renewal of Washington Square East into the Society Hill residential area embodied this approach. There, large-scale clearance of a wholesale food market gave way to three new high-rise towers by I. M. Pei (b. 1917). More unusual, however, was the combination of smaller-scale spot demolition, modern infill construction, and historic preservation that characterized the row houses west and south of the towers. Under the guidance of Society Hill resident and National Park Service architect Charles Peterson (1906-2004), historic preservation selectively restored the neighborhood’s Georgian and Federal past. At the same time, it also eradicated the encroachments of most late nineteenth- and twentieth-century architecture, mixed-use and multifamily properties, and industrial facilities. Bacon also inserted park space and greenways to provide brick- and tree-lined pedestrian routes traversing the neighborhood. The adjacent Penn’s Landing project, along the waterfront, revitalized park and cultural spaces aimed at tourists. Most of Society Hill’s previous residents—including largely Eastern European and African American renters—were replaced with more affluent owners who were able to afford the costs of single-family home rehabilitation. Although heralded for its embrace of preservation, the project also offered an early example of gentrification.

Not all housing projects focused on the upper class. In the sixteen thousand sparsely populated acres of the Far Northeast, Bacon aimed to apply suburban-style neighborhood planning principles to an urban setting. The proposal included superblocks with clustered housing, open space, and pedestrian pathways. Surrounding these superblocks, looped streets responded to the topography, while arterial streets and mass transportation offered more distant connections on the periphery. This model would counter both developers’ interest in building more familiar row houses and existing community members’ preferences for suburban-style tract housing. By contrast with typical redevelopment, the city did not own this land, and much of it was unbuilt. Thus, the Planning Commission’s main role was to develop subdivision plans to guide future development. The realized results were mixed. Early projects lacked walkable shopping and mass transit connections, yielding auto-centric living after all. Yet, many of the streams endured, and the clustered row houses made the units affordable to working- and middle-class residents.

Building in part upon the CURA Study’s responsiveness to deindustrialization, the Far Northeast also became a destination for new industrial development that might otherwise have departed the city. In the postwar era, many longtime downtown industries were either being displaced by urban renewal or highways, or were just forsaking their multilevel buildings in search of suburban-style, single-story facilities. Between 1959 and 1970, the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC) financed over one hundred transactions involving moves to or expansion of industrial parks. In this way, the PIDC facilitated industrial decentralization, but still within city boundaries. Still, the majority of its support funded the renovation of existing buildings in the inner city. Although this included declining minority neighborhoods, most of the employment opportunities went to white workers. In other parts of the city, such as West Philadelphia’s University City Science Center, more service-oriented industries like education and medicine also benefited from urban renewal partnerships.

Big Plans for Eastwick

Industrial development also clustered in Eastwick, a three-thousand-acre neighborhood in southwestern Philadelphia. The vast majority of the housing across all of Eastwick was in good repair, with the northwestern portion of the area—consisting mainly of rowhouses occupied by roughly one-third of Eastwick’s population—being particularly well-planned and -maintained. The neighborhood’s southern section, however, was less densely built and lacked necessary public infrastructure, including sewers and sufficiently paved roads. This was a particular challenge given the marshy nature of this landscape. The urban renewal plan for a “city-within-a-city” aimed to make Eastwick the largest redevelopment project in the country by merging housing and industry. Planners targeted twenty thousand jobs and homes for up to sixty thousand people in racially integrated development. While these goals were not fully met, the project did yield many blue-collar jobs and lower middle-income housing units. But these accomplishments came at the cost of the preexisting integrated community, which had unsuccessfully protested against the project from the outset.

Citizen opposition at Eastwick was not atypical. By the 1960s and 1970s, urban renewal projects were inciting increasing protest across the country. Critics charged that the program was synonymous with “Negro removal,” given that African Americans and other minority residents were the disproportionate victims of displacement. Federal legislation required the relocation of previous residents into safe and sanitary homes, and Title II of the Housing Act of 1949 included provisions for additional public housing construction. But, even improved physical environments could not make up for the psychosocial consequences—or “root shock”—that accompanied the breakup of close communities. Not all residents were eligible for public housing, but those who found accommodations there often suffered the relatively rapid decline of many of these new projects. For example, even Louis Kahn’s (1901-74) thoughtfully designed Mill Creek project, consisting of towers amidst a landscaped park in West Philadelphia, ultimately ended in demolition. Further opposition to urban renewal—from Jane Jacobs (1916-2006) among others—decried its destruction of still-vital neighborhoods and solid buildings, the vague definitions of slums and blight, and the failure of the program to realize many of its intended economic gains.

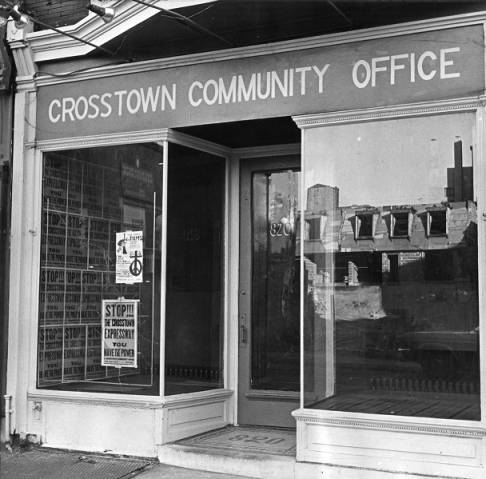

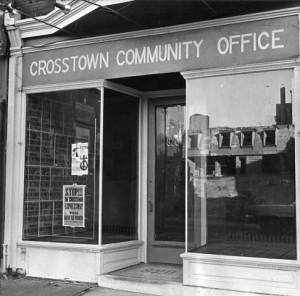

Postwar freeway development, funded through the Interstate Defense and Highway Act of 1956, often linked in with urban renewal projects and caused similar kinds of displacement. The massive destruction of these highways incited protests that sometimes stopped the bulldozer in its tracks. For example, the prolonged efforts of a diverse coalition halted the Crosstown Expressway that would have eradicated a significant African American neighborhood and commercial corridor while dividing Center City from South Philadelphia.

Whereas urban renewal was characterized by top-down efforts focused on physical design, the countermovements that developed in response advocated for bottom-up, community-led approaches aimed at social and economic revitalization. New federal urban renewal grants ceased with the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, which supported Community Development Block Grants with more diverse, local applications instead. But the legacies of postwar urban renewal continued to endure. They survived through the contemporary remaking of unsuccessful renewal projects, the preservation of other built projects as they reached the fiftieth anniversary mark, and ideally the application of lessons learned to the attempted revitalization of twenty-first-century cities.

Francesca Russello Ammon is Assistant Professor of City and Regional Planning and Historic Preservation at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research focuses on the history and culture of the built environment. She is the author of Bulldozer: Demolition and Clearance of the Postwar Landscape (Yale University Press, 2016). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Note: This essay was edited in February 2020. The name of the architecture firm responsible for the Gallery was corrected to Bower & Fradley, and the description of Eastwick was edited to reflect the state of the neighborhood prior to demolition.

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Edmund Bacon, architect of modern Philadelphia, and champion of skateboarders (WHYY, May 22, 2013)

- Franklin Square Park celebrates decadelong resurgence (WHYY, March29, 2016)

- In Philadelphia, a discussion about urban renewal and the 'trauma' of eminent domain (WHYY, April 8, 2016)

- Revitalization stirs up memories of a time Sharswood pulsed with all that jazz (WHYY, August 30, 2016)

- A 1940s documentary about housing and poverty in Philadelphia, and progress since then (WHYY, December 20, 2016)

- The Gallery: Past, Present, and Future (WHYY, October 23, 2018)

Links

- Edmund N. Bacon’s Pitch for Center City’s Revival: Form, Design and The City (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Urban Renewal: The Remaking of Society Hill (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment vis YouTube)

- Ed Bacon, In Perspective (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Philadelphia City Planning Commisssion

- Nearly 60 years later, city starts over in Eastwick (Philly.com, August 16, 2016)

- Renewing Inequality: Urban Renewal, Family Displacements, and Race, 1955-66 (University of Richmond Digital Scholarship Lab)