Memorial Day

Essay

Memorial Day, the last Monday in May, has been observed in the Greater Philadelphia area since the 1860s. The springtime holiday is considered the United States’ first multiracial, multiethnic commemoration and the kickoff of the summertime season. However, Memorial Day’s meanings and origin stories have been debated since its creation, and the holiday’s roots have been both contested and deeply enmeshed with the remaking of American memory in the decades following the Civil War. Each spring, generations of Philadelphians have participated in Memorial Day traditions upholding the meanings of the holiday’s past and shaping the direction of celebrations to come.

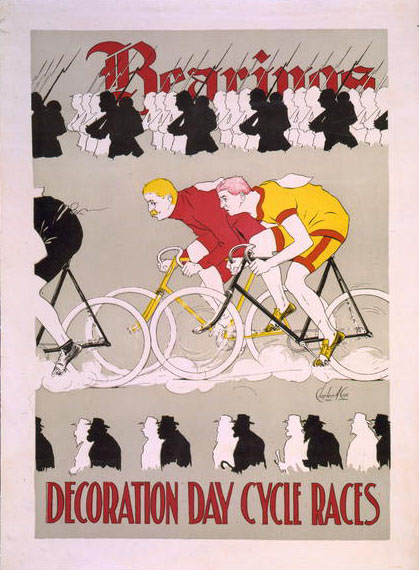

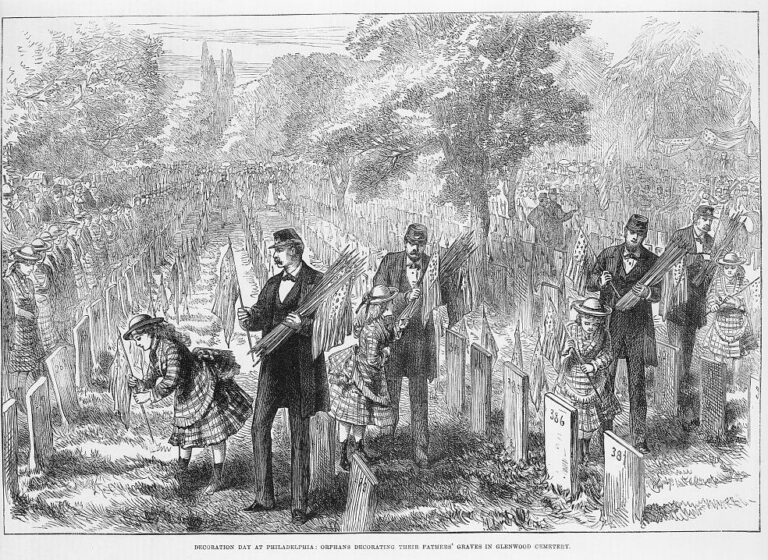

In the years during and immediately following the American Civil War (1861-65), grave decoration, the ritual of adorning burial sites with flowers or small tokens for the dead, led to Memorial Day’s original name, Decoration Day. In the former Confederacy, the Columbus (Georgia) Ladies’ Memorial Association is often credited with originating Memorial Day on April 26, 1866. Founding member Mary Ann Williams (1821-74) declared the purpose to “. . . keep alive the memory of the debt we owe [the Confederate dead].” Similarly, in northern cities and towns local and state governments created cemeteries for Union dead and heeded the call from the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) and its commander-in-chief John Alexander Logan (1826-86) to designate May 30, 1868, “for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion.” The late May date was chosen so the flowers used to decorate graves would be in full bloom. Community participation in Decoration Days often included speeches, church services, musical performances, and parades to honor veterans.

In Bucks County, the city of Doylestown has claimed to host the oldest continuous parade, citing a start date of May 30, 1868. In Philadelphia, Laurel Hill Cemetery was the site of the first Decoration Day observance, also on May 30, 1868. The bucolic burial grounds became the final resting place of several Civil War veterans, including General George Meade (1815-72), who defeated Robert E. Lee (1807-70) and the Confederate army at the Battle of Gettysburg.

While Decoration Day observances in the North and South shared many practices in common, including grave decoration, the “Decoration Day” holiday’s connections to the GAR and the valorization of Union soldiers led many Southerners to alternately use “Memorial Day” or “Confederate Memorial Day” to commemorate their dead. Still, not all Southerners chose to memorialize the Confederacy. On May 1, 1865, a group primarily composed of recently emancipated African Americans honored 257 Union troops left behind at a Confederate mass grave site in Charleston, South Carolina. The group organized the remains and reburied the bodies, created headstones, and decorated the graves with flowers, as almost ten thousand people gathered to march and mourn the soldiers.

The Twentieth Century

By the start of the twentieth century, Decoration Days had grown in popularity and gradually lost their association with the Civil War as the generations directly involved died and the rift between the Union and the former Confederacy significantly diminished. Americans subsequently moved on to mourn those who had died fighting overseas in World War I (1914-18). During this period, the poem “In Flanders Fields” by Canadian Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae (1872-1918) became a popular mourning text and red poppies, associated with the poem, became the flower of choice for decoration of graves or one’s own clothing. “Memorial Day” also supplanted “Decoration Day” as the more popular title for the holiday, as it encompassed a more general theme of remembrance.

In the years following both World War I and II, Philadelphians erected statues and sculptures to memorialize fallen soldiers, including the Smith Memorial Arch (1912) on the Avenue of the Republic in Fairmount Park, Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial (1927) on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway between Twentieth and Twenty-First Streets, and the World War I Aero Memorial (1939) in Logan Square. Some sites, like the Tomb of the Unknown Revolutionary War Solider in Washington Square (1957) and the Vietnam Memorial (1987) hosted annual Memorial Day ceremonies that included the solemn laying of wreaths, singing of the national anthem, and a twenty-one-gun salute to honor the dead.

In 1950, the United States Congress passed a joint resolution requesting that the president proclaim a “Prayer for Peace” on each Memorial Day. In 1967, Congress officially declared May 30, “Memorial Day,” a federal holiday. In 1968, the passage of the Uniform Monday Holiday Act moved Memorial Day to the fourth Monday in May, creating an annual three-day weekend for federal employees. This development notably delighted the travel industry and dismayed some veterans’ groups, who worried the long weekend would overshadow the holiday’s traditionally solemn purpose.

Throughout the second half of the twentieth century across the Greater Philadelphia area, the somber act of grave decoration or tributes to fallen soldiers increasingly gave way to parties, cookouts, and leisure activities that signaled the official start of summer. In New Jersey, while many towns hosted Memorial Day parades, the holiday was most popular as the official opening of the beaches and boardwalks in towns along the shore. In 1964, the winner of the “Miss Mermaid” competition symbolically held the “key to the Atlantic Ocean” in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to signify the start of the summer. In Pennsylvania, Memorial Day Weekend marked the opening of pools at many state parks, as well as Philadelphia’s spray grounds. In Philadelphia, the long weekend also offered festivals, fireworks, and special programs at local museums for tourists and residents alike. In the Bridesburg neighborhood, the local VFW and American Legion chapters raised funds for their Memorial Day parade through a Memorial Day 5k and 1 mile Honor Race.

Twenty-First Century

By the twenty-first century, many Americans marked Memorial Day with recreation or shopping rather than paying homage to those who died while fighting in the armed services. However, local VFW, American Legion, and other veterans continued to host traditional Memorial Day ceremonies. At the Philadelphia National Cemetery in the West Oak Lane neighborhood, graves have been decorated with American flags. In Laurel Hill Cemetery, attendees annually have recreated the original GAR Decoration Day Service of 1868 with speeches, music, and grave decoration. In 2021 President Joseph Biden (b. 1942) visited New Castle, Delaware, and addressed those gathered in observance at War Memorial Plaza on Memorial Day Weekend.

For some, the holiday had grown to encompass memorializing Americans who have died outside of war. Memorial Day 2020 fell on May 25, the same day George Floyd (1973-2020), an unarmed Black man, was killed in the custody of a white police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Video footage of Floyd’s murder quickly circulated online and inspired protests in cities and towns across the country. Participants demanded an end to police brutality, racism, and white supremacy, often while repeating the names of those killed extrajudicially by police. In Philadelphia, protests lasted from May 30 to June 23 and resulted in the removal of a mural and memorial statue honoring Frank Rizzo (1920-91), a former police chief and mayor accused of perpetuating racism and bias in the city. The protests shed light on the ongoing debate over how and why we choose to memorialize the past.

By May 2021, after half a million Americans had died from Covid-19 caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus and vaccines became more widely available, Pennsylvania and New Jersey “reopened” for Memorial Day by lifting almost all Covid-19 gathering restrictions. Philadelphia, while keeping some restrictions in place, encouraged tourists to visit the city. In South Jersey, Absecon, Glassboro, Vineland, and Wildwood hosted parades and the Battleship New Jersey in Camden hosted a wreath ceremony on the Delaware River.

Despite optimistic Memorial Day reopening celebrations, rising pandemic death tolls prompted calls across the United States for a “Covid Memorial Day” at the beginning of March. Across the Delaware Valley, groups came together to remember lost community members in various ways throughout the year. The Delaware COVID-19 Garden Remembrance Memorial at the First Presbyterian Church of Dover opened to the public on Memorial Day weekend in 2021, and the “Rami’s Heart COVID 19 Memorial” was dedicated at Allaire Community Farm in New Jersey on September 17, 2021.

As Americans updated Memorial Day practices to encompass modern feelings of grief and loss, they continued to redefine the act of remembering and who or what is worthy of memorial. In the face of national tragedies, cities and towns created and recreated the traditions of the past to better reflect their present reality and hopes for the future.

Mikaela Maria is a public historian and administrative professional living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Author information current at date of publication.)

Copyright 2023, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History