Ceramics

Essay

Once on par with other industries that gave Greater Philadelphia its reputation as the “Workshop of the World,” ceramic production played a key role in the region’s economic and artistic significance. Innovative makers and entrepreneurs produced a spectrum of utilitarian pottery and refined luxury goods, making visible the shifting patterns of consumption, taste, and technology use. While the height of ceramics production coincided with industrialization in the nineteenth century, the medium’s ubiquity in daily life continued to support Philadelphia-area pottery-making on a smaller scale into the twenty-first century.

Prior to European colonization, abundant local clay deposits supported a continuous indigenous pottery tradition in the region for around three thousand years. The native Lenni Lenape People and their ancestors made, used, and traded earthenware ceramics across a broad territory, throughout the Woodland Period and after (roughly 500 BCE-1500 CE). Early prehistoric vessels were decorated by pressing a cord into the wet clay, while later pots often feature incised geometric patterns around the rim or shoulder. Hand-built and fired without kilns, some Lenape vessels for daily and ceremonial use reached impressive sizes.

Early European settlers in the region drew on the same clay deposits to produce a wide range of useful wares for use in homes, taverns, or dairies. Ceramics with industrial or architectural purposes, including building components like bricks, roof tiles, drain pipes, and chimney liners were also produced from an early date. The porous, low-fire earthenware that formed most of these functional products required glazing to be waterproof. Intensive labor characterized each step of the production process: cutting clay from the ground, preparing and refining it, and shaping, decorating, and firing finished vessels and other objects. Workshops tended to be organized through the longstanding tradition of apprenticeship, although colonial craft was far less formal or regulated than its European precedents, and many potters supplemented their incomes with additional lines of business.

One of the most distinctive styles of early ceramics in the Philadelphia area arrived with the influx of German-speaking settlers to the region in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Pennsylvania Germans (or Pennsylvania Dutch, as the community is often known, based on a corruption of “Deutsch”) produced great quantities of red-bodied earthenware using earthy glazes (typically containing iron oxide, manganese, copper oxide, and cobalt), colored slip (thin, liquid clay), and sgraffito (incised marks) to create a wide variety of decorative effects. The Pennsylvania German tradition in ceramics and other crafts continued into later centuries, even as the mid-eighteenth-century discovery of higher-grade stoneware clays in northern New Jersey and an increase in luxury production throughout the colonies shifted the economic center of gravity away from these more rustic wares.

Casting Off Imported Wares

For Anglo-Europeans, establishing pottery production on a commercial scale aided in casting off reliance on imported wares, thus contributing to economic and political independence from Britain. Philadelphia-area manufactories benefited from the knowledge and skill of émigrés from Staffordshire, the heart of Britain’s ceramics industry. The American China Manufactory, the joint venture of British-born Gousse Bonnin (c. 1741-?) and Philadelphia native George Anthony Morris (c. 1742-73), began operations in 1770 at a site on Front Street and the newly built China Street (later renamed Alter Street) near Philadelphia’s Delaware River waterfront. It became one of the earliest American enterprises to produce porcelain, a type of ceramic highly valued for its physical and visual refinement. The complexity and secrecy surrounding the making of porcelain (which had been exclusive to China for several centuries) fueled demand for the China trade, and scientific and entrepreneurial investment in porcelain production throughout eighteenth-century Europe made and broke personal and state fortunes. Enabled by nearby sources of porcelain ingredients (kaolin and feldspar) in Delaware and New Jersey, Bonnin and Morris’s wares represented not only an American attempt at economic self-determination, but also demonstrated the intellectual and artistic capacity of the colonial states. Despite these ambitions, the manufactory proved fiscally unsustainable, facing stiff competition in quality and price with English imports and struggling to sufficiently compensate its laborers. Although the American China Manufactory ceased operations in 1772, its standing as an early indicator of Philadelphia’s industrial achievements remained.

Objects of Euro-American luxury consumption often survived in museums and private collections, but ceramics were also an important part of daily life for laborers, free and enslaved Africans, and other marginalized groups in the colonial period and early Republic. Sturdy vessels made by Africans and African Americans, termed “colonoware” by archaeologists, originated primarily in southeastern colonies and the Caribbean, but important finds in Philadelphia have shown a wide geographic distribution between the late seventeenth and mid-nineteenth centuries. Alongside such vernacular pottery production, fragments of fine imported wares found at sites associated with African and African American communities and individuals in Philadelphia, including the kitchens and slave quarters of the former President’s House on Market Street, have shown that more expensive forms of ceramics could also move across social and economic divides.

By the 1810 United States Census of Manufactures, Pennsylvania’s leadership in ceramics production had been firmly established: the commonwealth hosted 164 of the 194 potteries in the nation. Despite the difficulties encountered by Bonnin and Morris, Philadelphia’s situation as an intersection between land and maritime transport made it a center for this production. As America’s manufacturing sector grew, the project of reducing national dependence on European imports continued. The William Ellis Tucker China Manufactory (active 1826-38), located at Twenty-Third and Chestnut Streets in Philadelphia, made largely French-styled porcelain and found regular success at exhibitions hosted by Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute, which aimed to support domestic fine ceramics and other luxury industries. Despite its successful porcelain recipe and favorable reception of its designs, the Tucker factory faced continual financial difficulties that revealed the unstable nature of luxury industries, which relied on rapidly shifting tastes and complex manufacturing processes.

Mechanization and Expansion

Over the course of the nineteenth century, like many other industries the ceramics industry experienced mechanization and expansion. Steam-powered machinery for digging and working clay, along with larger kilns fired by coal rather than wood, enabled some manufacturers to grow from small family firms to industrial-scale producers. Railroads fostered better access to inland clay deposits and more reliable distribution of finished wares to customers. Machine-based molding techniques, adapted to mass production from their origins in small potteries, allowed higher output and better consistency. Techniques for transferring patterns and graphic decoration onto blank ceramic shapes saved time and the high cost of hand-painting, although fine handcraft traditions were still valued for high-style wares aimed at elite consumers.

These technological changes reshaped the economic, demographic, and geographic landscapes of ceramics production. In central urban areas, smaller, older potteries closed in the face of population growth, rising land values, and reduced tolerance for manufacturing inside the city’s bounds. Larger firms moved to the edges of urban centers, exploiting low-skill, low-wage labor that allowed them to undercut more traditional potteries (which required higher skill, higher wages, and higher prices for finished wares). In the latter half of the nineteenth century, New Jersey—especially Trenton—became a key center of ceramics production in the United States, mostly because of the confluence there of land and water transportation and its specialization in sanitary ware for institutional customers. Philadelphia-area firms continued to expand their holdings of clay deposits in the interior of Pennsylvania (particularly Lancaster and Cumberland Counties) and diversify their merchandise in response to a growing middle-class consumer base.

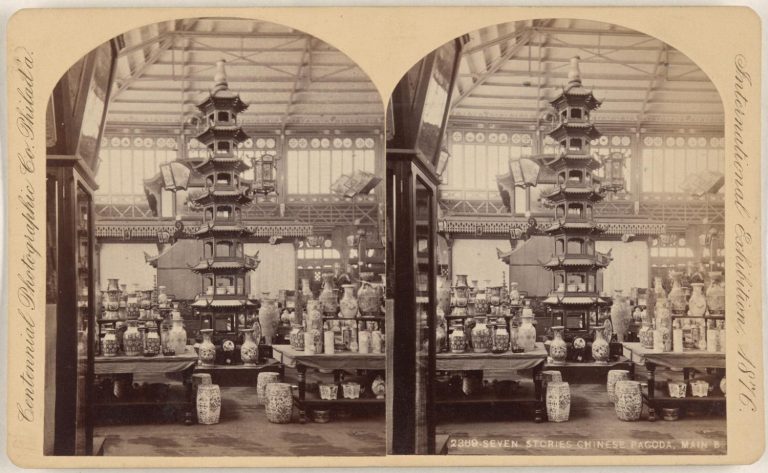

Reflecting the public clout of the pottery business, ceramics were one of the most commented-upon categories of industrial art on view at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition. Displays of ceramics by numerous exhibitors from Europe, Asia, and the United States provided a global view of techniques and styles through both contemporary and historic objects. Many commentators argued that the distinct styles and high degree of workmanship evident in Chinese and Japanese ceramics could be a fresh source of inspiration for domestic producers. European firms with long-standing reputations also displayed wares reinterpreting the historic styles of classical antiquity or the Renaissance, issuing a challenge to their younger American counterparts on the bases of quality and refinement. The Centennial ceramic displays captured many of the defining impulses of nineteenth-century decorative arts—orientalism and historic revivalism, the embrace of handcraft amid increasing industrialization, and concerns about quality in mass production.

These trends also informed the wide diversity of ceramics produced in the Philadelphia region in the later nineteenth century. Examples include J. E. Jeffords & Company, which operated the Philadelphia City Pottery at Edgemont Street and Lehigh Avenue in the Richmond area beginning in the 1868, as well as Ott & Brewer in Trenton, New Jersey, both of which produced highly decorative, orientalist ceramics; Griffen, Smith & Hill Company in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, whose offerings included fashionable majolica and Renaissance-revival objects; the American Crockery Company in Trenton, producing more affordable transferware; and Charles Wingender & Brother, established in 1881 in Haddonfield, New Jersey, by German immigrants who worked to revive the Central European tradition of durable salt-glazed stoneware.

Post-Centennial Institutions

Another impact of the Centennial Exhibition was the establishment of the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (later separated into the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art, forerunner of the University of the Arts). Ceramics acquired from the exhibition formed a major part of the institution’s founding collection, intended to serve as didactic examples to raise the quality of local manufacturing. An early curator and eventual director of the museum, archaeologist Edwin Atlee Barber (1851-1916) was a respected authority on ceramics history, and his publications and acquisitions reinforced the medium as an area of focus for the young institution. While its primary educational mission mainly addressed industry-based makers, the museum and school also promoted china-painting as a respectable income-earning activity for genteel women. This vein of ceramics history is less well-documented or collected in archives or cultural institutions, illustrating the gendered divisions between the professional, “masculine” world of manufacturing and the domestic, amateur, “feminine” sphere of home industry—both in nineteenth-century social terms as well as in subsequent history-writing.

Reactions against mechanization and industrialization—and the social and economic upheavals that accompanied them—led to a surge of interest in small-scale craft production in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Building on the writings and practices of English design reformers, the Arts and Crafts movement in the United States focused on the individual (often rural) craftsperson as a vehicle of both social and artistic change. Ceramics were one of the most financially successful veins of Arts and Crafts activity, and firms like Trenton-based Lenox Incorporated or Flemington, New Jersey-based Fulper Pottery participated in a larger vogue for “art pottery” that suggested handcraft and connections to nature. More radical art colony projects, like Rose Valley outside Philadelphia in Delaware County, sought to construct daily life as an artistic practice, inviting potters like William P. Jervis (1851–1925) to teach craft skills and sell work to support the community.

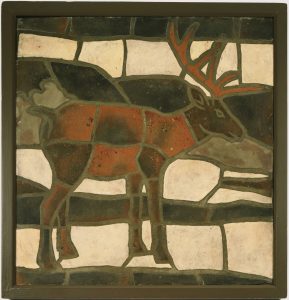

The region’s urban growth in the early twentieth century provided a robust market for architectural ceramics, especially efficiently produced tilework. One of the frontrunners in this arena was the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works, established in 1898 in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, by Henry Chapman Mercer, a notable archaeologist and collector whose interest in the history of Germanic pottery in colonial America led him into the ceramics field. Like many other Arts and Crafts advocates, Mercer looked to the arts of the Middle Ages to inform his designs, producing mosaics and other decoration for buildings throughout the Philadelphia area and elsewhere. Alongside the more romantic Arts and Crafts approach, industrial-scale ceramics production continued unabated, and the construction of Philadelphia’s first skyscrapers spurred architectural terra-cotta ornament to new heights. Many of the region’s buildings dating from the late 1910s into the 1930s sported Art Deco ceramic ornament in patterns and bright colors that suggested the dynamism and modernity of the machine-age city.

After the Second World War, an influx of G.I. Bill students and rising national interest in craft education supported the founding or expansion of ceramics programs at Philadelphia-area institutions including Temple University’s Tyler School of Art, Moore College of Art and Design, Philadelphia College of the Arts (later the University of the Arts), and Beaver College (later Arcadia University). Faculty and graduates of these programs contributed to a turn in the broader field of craft toward more conceptual and sculptural work, moving away from the production of necessarily functional objects and allying themselves with avant-garde artistic ideas. The tensions between notions of utility and artistry and the contested borders between craft, art, and design continued to characterize the ceramics field in subsequent decades.

Ceramists as Teachers

Teaching provided ceramists a secure income as well as time and resources for their work, and many of Philadelphia’s best-known makers cultivated careers as artist-educators, often enjoying lengthy tenures. Rudolf Staffel (1911–2002) taught at the Tyler School of Art for thirty-eight years; Staffel’s student Paula Winokur (1935–2018) taught for three decades at Beaver College, while her husband Robert (b. 1933) taught at Tyler; and William Daley (b. 1925) joined the Philadelphia College of the Arts faculty in 1957 and taught there for thirty-three years. Other notable ceramists who studied or worked in the region bridged multiple geographies over the course of their careers. Robert Turner (1913–2005) studied at Swarthmore and the Pennsylvania Academy before teaching at the experimental Black Mountain College in North Carolina; Byron Temple (1933–2002) operated a studio in Lambertville, New Jersey, while teaching in several New York City programs. Temple’s assistant James Makins (b. 1946) pursued graduate study at the prestigious Cranbrook Art Academy in Michigan before returning to teach at University of the Arts from 1990.

Non-academic cultural organizations also played an important role in the postwar visibility of ceramic art. The Clay Studio was founded in 1974 by a group of Tyler School of Art students and faculty seeking studio space. Originally housed on Orianna Street near Temple University, by 1979 it had transformed into a nonprofit offering public classes, artist residencies, and selling exhibitions for ceramists in the region, moving to Second Street in Old City the next year. Private collectors and commercial galleries also responded to the growing interest in—and market for—contemporary ceramics. Helen Drutt English (b. 1930), a founding member of the Philadelphia Council of Professional Craftsmen in 1967, established a respected Center City gallery that mounted exhibitions of nationally and internationally prominent ceramists during its operation from 1973 to 2002.

In the twenty-first century, ceramics remained a strong presence in the artistic and everyday life of the Philadelphia region, as retailers, galleries, and museums interpreted the creative, economic, and social importance of the medium. The juried Philadelphia Craft Show, running since 1977 as a fundraising project of the Women’s Committee of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, remained a prominent venue for ceramists to exhibit and sell their work, and in 2018 the Clay Studio began planning a move from Old City to a much larger facility for expanded studio and educational offerings. Younger generations of makers like Winnie Owens Hart (b. 1949), Lizbeth Stewart (1948–2013), and Cristina Tufiño (b. 1982)—ceramists who trained or worked in Philadelphia while participating in global artistic conversations—drove the medium in new aesthetic and conceptual directions, exploring how ceramic artworks might critique issues of racial, gender, or economic disparities.

Since its earliest days as a center of making, the Philadelphia region has played a key role in the history of American ceramics—a medium that, at its best, represents a combination of technological knowledge and artistic excellence. Although the mass-production of pottery tapered off over the twentieth century, a strong ceramist community ensured that Philadelphia’s reputation for ceramic innovations continued beyond the region’s transition to a post-industrial economy.

Colin Fanning is a PhD candidate at the Bard Graduate Center, where his research focuses on the history of American design education. From 2014 to 2017, he was Curatorial Fellow for European Decorative Arts and Sculpture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History