Irish (The) and Ireland

Essay

Contacts between the Philadelphia region and Ireland began in the late seventeenth century, shortly after the creation of Penn’s colony. Long a part of the urban fabric of Philadelphia, Irish Catholics endured nativist assaults of the Bible Riots of 1844 and did not see one of their own become mayor until James H. J. Tate, who served from 1962 to 1972. By the twenty-first century, the Irish continued to exert significant cultural and political influence in the region, especially in South and Northeast Philadelphia and in surrounding suburban counties.

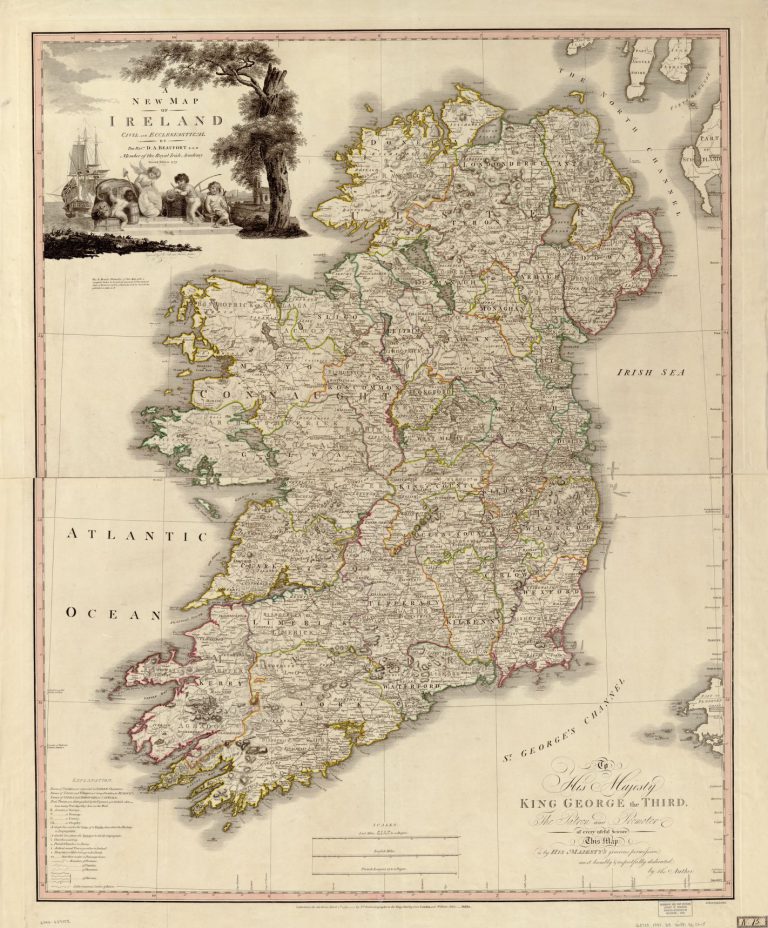

The region’s ties to Ireland extend to Pennsylvania’s founder, William Penn (1644-1718), who was part Irish on his mother’s side. His father, Sir William Penn (1621-70), aided in the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland and was rewarded with land confiscated from Irish Catholics in Macroom, in County Cork. Named an admiral in the English navy, Sir William also assisted in the Stuart Restoration of Charles II and received more land in Kinsale, Shangarry, and Cork City. William Penn himself helped suppress a mutiny in Carrickfergus, County Antrim, in 1666, and became the English purveyor of goods in Cork. He converted to Quakerism in Cork in 1667.

Turmoil in Ireland in the decades prior to the founding of Pennsylvania produced conditions that prompted emigration to America. In the seventeenth century, the English under the Catholic Stuart king, James I, began a colonial endeavor called the Ulster Plantation, which brought thousands of English and Lowland Scots into Ireland and dispossessed native Irish from their lands in counties Antrim, Down, Armagh, Derry, Tyrone, and Fermanagh. Many of the Scots Irish colonists, facing economic marginalization by English and Scottish merchants who feared competition from less expensive Ulster products, fled the island for America. Over two hundred thousand Scots Irish settled in the British North American colonies in the eighteenth century before the American Revolution. Arriving in the ports of Philadelphia and New Castle, many Ulster-born immigrants pressed on into the interior to the Shenandoah frontier to escape the colonial government.

During the eighteenth century, a combination of religious, economic, and other conflicts fueled immigration of Irish Catholics. Many farmers dispossessed of their land by colonization in Ireland in the late seventeenth century were Catholic. To escape long-term hardships during the Protestant Ascendency, when Anglican Protestants loyal to the monarchy held all political power, many Catholics emigrated and some began arriving in Philadelphia. One result was the construction in 1733 of the earliest Catholic Church in British North America—Old St. Joseph’s—in Willings Alley south of Walnut Street. Another parish, Old St. Mary’s, was founded in 1763 on Fourth Street between Manning and Locust Streets. Newly arrived Irish (many from Ulster) helped push the city’s Catholic population to one thousand in 1785, according to an estimate by Bishop John Carroll (1735-1815).

Riverside Settlement

Most Catholic Irish immigrants settled in neighborhoods adjacent to the Delaware River waterfront, and over time followed both skilled and unskilled employment opportunities into other working-class neighborhoods stretching north along the river. These neighborhoods included some that were later termed the “river wards” (including Northern Liberties, Kensington, Port Richmond, Bridesburg, Frankford, Wissinoming, Tacony, and Torresdale), as well as some to the northwest (including Germantown, East Falls, and Manayunk) and southwest (including Kingsessing, Elmwood, and Eastwick). Other Irish immigrants settled west and north of Philadelphia in Delaware, Montgomery, Chester, and Bucks Counties; in the New Jersey counties of Gloucester, Camden, Burlington, and Mercer; and in the northern part of New Castle County, Delaware.

In addition to churches, organizations and rituals united the Irish as a community and sustained Irish culture. The Society of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick was established in Philadelphia at Miller’s Tavern on March 17, 1771, as a charitable organization for the relief of Irish immigrants. Created as a nonsectarian organization, its members were native-born Irishmen or their sons. It sponsored the city’s first St. Patrick’s Day Parade at its founding in 1771.

Several Catholic immigrant members of the Friendly Sons, including Stephen Moylan (1737-1811), John Barry (1745-1803), and Thomas Fitzsimmons (1741-1811), were among about eight hundred Catholics from Philadelphia who served in the American Revolution. Wexford-born Captain Thomas Fitzsimmons served as a delegate to the Continental Congress and became one of only two Catholic signers of the U.S. Constitution. He later served in the U.S. House of Representatives. Financier John Nixon (1733-1808), whose father was from County Wexford, did the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence, at the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall). Thomas McKean (1734-1817), of Scots Irish parentage, served as the chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court from 1777 to 1799.

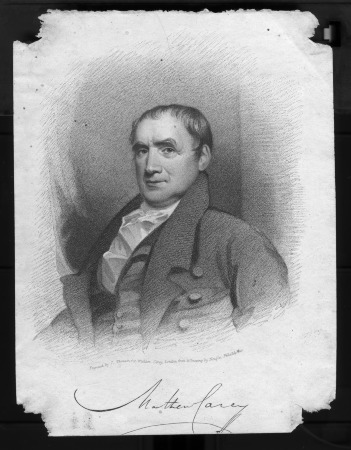

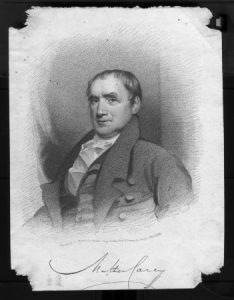

Some Irishmen made a mark in Philadelphia business. For example, John Barclay (1749-1824), born in County Donegal, helped found the Insurance Company of North America in 1792. Joseph Tagert (1758-1849), born in County Tyrone, served for forty years as president of the Farmers and Mechanics Bank, which was founded in 1809 and became the largest bank in Philadelphia by the second half of the nineteenth century). He was also the president of the Friendly Sons from 1818 to 1849. Dublin-born Matthew Carey (1760-1839) published newspapers and books, including the first American Douay Reims version of the Bible for Catholics. In 1790 he founded and served as the first secretary of the Hibernian Society for the Relief of Immigrants, which provided charitable aid to Irish immigrants arriving in Philadelphia. It was one of the earliest of such immigrant relief organizations in the United States.

Railroad and Canal Labor

A new wave of Irish Catholics came in the nineteenth century, many of them individuals seeking employment. Most had been excluded from the emerging industrial economy in Ireland and had never earned a wage for their work on rural farms. Between the War of 1812 and the Great Hunger produced by the potato famine of the 1840s, some five hundred thousand Irish Catholics came to the United States, drawn by prospects for work. From the 1820s through the 1840s, these immigrant laborers built the early infrastructure of rail lines and canals all along the East Coast, and in particular in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, and New York, for twenty-five cents a day. A substantial number came to work on the Main Line of Public Works in Pennsylvania, on sections of the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad and the Allegheny Portage Railroad, and on sections of the Pennsylvania Canal. Irish immigrants were also drawn to work at the duPont family’s Eleutherian Mills gunpowder plant on the Brandywine Creek north of Wilmington in New Castle County, Delaware. The mill, which opened in 1802, eventually employed so many Irish (and Italian) Catholic laborers that in 1841 the duPonts built a Catholic church for them, St. Joseph on the Brandywine, on Barley Mill Road in Greenville, Delaware.

Irish Catholic immigrants faced great depths of animosity during this era. Historian Dennis Clark summarized the roots of the bigotry in his seminal work The Irish in Philadelphia: Ten Generations of the Urban Experience: “The antipathy toward them rested not only on their reputation for violence and their religious difference from the bulk of the city’s natives, but also upon their competition for jobs at the lowest occupational levels, their menial status, their foreign aspect and clannishness, and their notorious intemperance.”

Sectarian violence was common. In 1831, the Philadelphia Orange Riots erupted between Irish Catholics and Irish Protestants over a Protestant parade commemorating Protestant King William III’s victory over Catholic James II at the Battle of the Boyne (1690). During the cholera epidemic of 1832, fifty-seven immigrant railroad workers from Donegal, Tyrone, and Derry died of cholera and violence at a site called Duffy’s Cut in Chester County (Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad mile 59), six weeks after arriving in Philadelphia. Contractor Philip Duffy (1783-1871), himself a Catholic immigrant, was a purveyor of his countrymen for the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad (P&C), the West Chester Railroad, and the Reading Railroad. He naturalized some of them and held indentures for others from his home in Port Richmond.

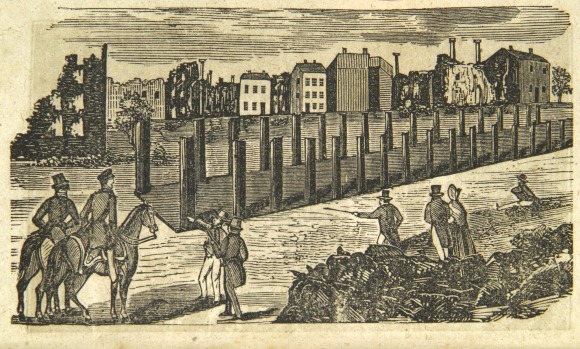

Kensington experienced riots in 1828, 1840, 1841, 1842, 1843, and most violently during the nativist riots of May and July 1844. The riots in Kensington and Southwark cost twenty deaths, about one hundred injuries, the loss of many Irish homes and businesses to fire, as well as the destruction of Sisters of Charity convent (Second and Phoenix Streets), and the churches of St. Michael (Second and Master Streets) and St. Augustine (Fourth Street south of Vine). In Southwark, a nativist mob shot cannons at St. Philip Neri Church (Queen Street), and the services of the state militia were required to quell the riot. The destructiveness of the riots led to police reform and the consolidation of suburban districts with the city. It also contributed to the establishment of the Catholic parochial school system, as controversy over using the King James Bible over the Catholic Douay Bible played a role in the riots. The evolving anti-Catholic atmosphere of Philadelphia fostered the growth of the school that became Villanova University, located in Radnor Township some ten miles from the city.

Irish Famine Relief Committee

By 1850, some seventy-two thousand Philadelphians were Irish-born immigrants—17.6 percent of the city’s total population—and more came in families than in earlier times. Ireland’s Great Hunger of 1845-52, caused by a potato blight and British policies of neglect and eviction, resulted in the death or emigration of a quarter of the Irish population by 1852. One million to one and a half million Irish emigrated abroad, with perhaps nine hundred thousand coming to the United States. The non-denominational Philadelphia Irish Famine Relief Committee formed to collect food, money, and clothing to help the starving population in Ireland. Quakers became particularly active in supporting famine relief.

In the second half of the nineteenth century following the Great Hunger, many Irish immigrants found work as common laborers on the railroads and canals. Others worked in Philadelphia factories, such as the hundreds of textile mills that dominated the industrial landscape in Kensington, Germantown, Port Richmond, and Manayunk, and the thousands of smaller workhouses scattered throughout the city. The Baldwin Locomotive Works employed many Irish laborers during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, first in Philadelphia and then Eddystone, Delaware County. Irishmen were drawn westward to work in textile mills in Delaware County, such as at Kellyville (Drexel Hill). A great many Irish women worked in domestic service in Philadelphia and surrounding communities, continuing the type of work long performed by poor Catholic women in the homes of wealthy Protestants in Ireland. Although many of the Irish worked in industry, after 1850 they were less likely than the Irish in Boston to be engaged in manual labor. As in other urban areas throughout the eastern United States, Irish Americans served in law enforcement and fire protection. According to Clark, between 1850 and 1870 the number of occupations held by Irish Philadelphians nearly doubled from thirty-two to sixty-two, demonstrating a degree of social mobility unknown to Irish Americans elsewhere at the time.

As the Irish population grew, the greater Philadelphia area became an increasingly receptive environment for Irish nationalists. The cause had local support as early as the eighteenth century. Irish revolutionary Theobald Wolfe Tone (1763-98) lived in Philadelphia, West Chester, and Downingtown in 1795 before going to France to secure support for the Society of United Irishmen. In 1880, Charles Stewart Parnell (1846-1891) came to Philadelphia to raise funds and awareness for the Irish National League, and by 1881, several dozen local branches of the Irish Land League formed. Tyrone-born Joseph McGarrity (1874-1940), who settled in Philadelphia, became one of the U.S. leaders of the Irish nationalist organization Clan-na-Gael, which raised funds for the struggle for Irish independence.

Many second and third-generation Irish Philadelphians rose to prominence in business and politics. Thomas Dolan (1834-1914) operated the Keystone Knitting Mills (later, Thomas Dolan and Company) at Hancock and Oxford Street and Columbia Avenue in Philadelphia, and then in Springfield, Delaware County, and later, the United Gas Improvement Company. He served as director of the Union League from 1884 to 1890. Morton McMichael (1807-79), of Scots Irish background (and nativist proclivities), became mayor of Philadelphia, serving 1866-69, and was one of the founders of the Union League. At the time of the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, the city’s Irish elite expressed confidence in their place in American society by unveiling the large, ornamental Catholic Total Abstinence Fountain in Fairmount Park. Featuring sculptures and portrait medallions of Irish-American heroes of the American Revolution and the Catholic Church, the fountain was a project of the Catholic Total Abstinence Union of America, which sought to curb drink among the Irish in America.

Irish in Catholic Church Hierarchy

Irishmen also came to dominate the hierarchy of the Catholic Church in Philadelphia, as they did in many other cities of the Atlantic Seaboard. Patrick John Ryan (1831-1911), born in County Tipperary, became Philadelphia’s second archbishop and oversaw construction of numerous churches and Catholic schools as the number of Catholics in the archdiocese grew to more than half a million during his tenure. The construction projects continued under the third archbishop of Philadelphia, Edmond Francis Prendergast (1843-1918), also from Tipperary. Prendergast was succeeded by Dennis J. Dougherty (1865-1951), an Irish-American from Ashland, Pennsylvania, whose parents were from County Mayo. Dougherty, who was made Philadelphia’s first cardinal in 1921, became the longest-serving archbishop in the history of the Philadelphia archdiocese (1918-1951). He opened 106 new parishes, 146 schools, seven nursing homes, seven orphanages, and a new cardinal’s residence on City Avenue.

Significant numbers of Irish Americans in the Philadelphia region also joined religious orders, including the Christian Brothers, Jesuits, Franciscans, Augustinians, Sisters of Charity, Sisters Servants of the Immaculata Heart of Mary, Sisters of St. Joseph, Sisters of Mercy, and Sisters of the Holy Child Jesus The Irish also had a significant regional impact in education, in parochial schools and at Catholic institutions of higher learning such as Villanova, St. Joseph’s, La Salle, Chestnut Hill, Rosemont, Immaculata, Cabrini, Gwynedd Mercy, and Neumann.

In the first few decades of the twentieth century, another half million Irish came to the United States, but far fewer after a national quota system was implemented in the 1920s. From the 1930s to the 1980s, perhaps 150,000 Irish arrived in the U.S., with severe drops during the world wars and during Northern Ireland’s “Troubles,” the conflict between Irish nationalists and the British government and their Unionist supporters.

Irish American politicians and civic groups flourished in the Philadelphia region in the twentieth and early twenty-first century. In 1962, James H.J. Tate became the first Irish Catholic mayor of Philadelphia, followed by William J. Green III (b. 1938) in 1980 and James Kenney (b. 1968) in 2016. Irish Americans also remained active as ward leaders and members of City Council in Philadelphia and in surrounding counties in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. The Friendly Sons of St. Patrick continued as a significant regional charitable organization, while additional Irish-American organizations and civic groups formed. The St. Patrick’s Day Parade, started in 1771 by members of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, was administered after 1952 by the Philadelphia St. Patrick’s Day Observance Association, which emphasized the essentially Catholic nature of the parade. The Commodore Barry Irish Center in Mount Airy, founded in 1958 and led for most of its existence by Donegal immigrant Vince Gallagher (b. 1944), served as a general meeting place for local Irish organizations and county societies. The Brehon Law Society of Philadelphia, founded in 1976, fostered the profession of law among Irish Americans and promoted an appreciation of Irish culture among jurists. The Irish Immigration and Pastoral Center opened in 1998 on South Cedar Lane in Upper Darby, Delaware County, to assist Irish immigrants. Numerous Ancient Order of Hibernians divisions were established in Philadelphia and nearby counties in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware, as well as schools of Irish traditional dance and bagpipe bands. Many Irish civic and business groups helped erect a bronze Irish Famine Memorial at Front Street near Penn’s landing in Philadelphia in 2003.

Suburban Migration

As with other ethnic groups, suburbanization trends that began in the 1950s reshaped where Irish Americans lived. Delaware County came to contain one of the most dense Irish-American populations in Pennsylvania, especially in Upper Darby, Havertown, and Crum Lynne. In the 1970s and 1980s, many Irish-Americans moved also from inner ring suburbs to communities farther from the city, westward into Montgomery and Chester Counties, northward to Bucks County, eastward to New Jersey, and southward to New Castle County, Delaware. By 2015, Pennsylvania had 2,137,575 self-identified residents of Irish extraction, the third-highest among states in the nation (but seventh in percentage of Irish Americans, at just over 16 percent). The highest concentrations of Irish Americans by county were in the southeastern part of Pennsylvania, including Delaware County (26.4 percent), Montgomery County (21.9 percent), and Philadelphia County (11.6 percent). The smaller state of Delaware had a higher percentage of Irish-Americans residing within it (over 130,000), at 16.6 percent of the total population. Wilmington’s population was 13 percent Irish American. New Jersey had more than 1.3 million Irish Americans, almost 16 percent of the state’s total population.

Philadelphians also sought to build and sustain business relationships between the region and Ireland through organizations such as the Irish-American Business Chamber and Network, founded in 1999 by Bill McLaughlin (b. 1945). In 2010, Philadelphia also gained a branch of the Irish Network-USA, established by the Irish government to promote cultural and business ties. American pharmaceutical companies and technology companies establishing branches in Ireland, and vice versa. By 2016, an estimated seven hundred American companies operated in Ireland, employing 150,000 Irish citizens, while some two hundred Irish companies operated in the U.S. and employed about the same number of American citizens. Irish companies setting up branches in the Delaware Valley included Adapt Pharma in Radnor, Delaware County, and S3 Group (a computer tech company), in Philadelphia.

Irish-Americans helped to define the labor force and build the industrial infrastructure of the Greater Philadelphia area since its earliest days. They heavily influenced the urban politics, educational system, and the Catholic Church in the region, and their culture and their traditions left an enduring imprint on the Delaware Valley.

William E. Watson is Professor of History at Immaculata University and Director of the Duffy’s Cut Project. He received his PhD in European history from the University of Pennsylvania in 1990. (Author information current at time of publication).

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Final lament for Irish immigrants treated roughly in life, death (WHYY, March 9, 2012)

- After 180 years, remains return to ancestral Irish home (WHYY, March 1, 2013)

- Remembering my Irish roots (WHYY, March 17, 2012)

- Is corned beef and cabbage really standard Irish fare? One expert says -- not so much (WHYY, March 14, 2014)

- Irish packaging firm to build plant in Delaware (WHYY, June 23, 2015)

- View Finders Philly puts on the green for Saint Patrick's Day [photos] (WHYY, March 13, 2017)