Liberty Bell

By Gary B. Nash | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

It began inconspicuously as a two-thousand-pound mass of unstable metal; it nearly ended up in the scrap heap; it cracked and lost its voice; it was all but forgotten. But then, gradually, it became a priceless national treasure. The Liberty Bell captured American affections and became a stand-in for the nation’s vaunted values: independence, freedom, unalienable rights, and equality. It became a touchstone of American identity as Americans adopted it, along with the flag, as a symbol of justice, the rule of law, and the guardian of sovereign rights.

The Liberty Bell started out simply as the bell commissioned by the colonial legislature of Pennsylvania to hang in the steeple of the State House in 1752 so that the growing city would have a bell with great carrying power to announce meetings of the legislature and toll for notable events. Cast in London, it cracked at its first testing at which point two artisans in Philadelphia, John Pass and John Stow, recast the bell. Around its brim, it carried words from the Old Testament: “Proclaim LIBERTY throughout all the Land unto all the Inhabitants thereof” (Leviticus, XXV, 10).

During the revolutionary era the State House bell became an accomplice in revolutionary politics. It rang out in 1765 to warn of the approach of an English ship sailing up the Delaware River to deliver stamped paper for implementing the hated Stamp Act. It tolled in 1768 to attract thousands gathering to protest the Townshend duties. Again it rang to assemble the citizenry in 1773 for a town meeting to protest the Tea Act. And then again, in 1774, the bell summoned Philadelphians to protest the Coercive Acts. On July 8, 1776, the bell is believed to have pealed as peopled massed in the State House yard to hear the sheriff of Philadelphia read the Declaration of Independence.

Bell Hidden From British

The State House bell had to sit out the British occupation of the city in 1777-78 because Philadelphians, knowing that the British would melt it down and convert it into bullets to be aimed at insurgent Americans, wrestled it down from the State House steeple and carried it by wagon to Allentown. But it was back in the city to toll the British surrender at Yorktown on October 24, 1781, and again to announce the signing of the Treaty of Paris with Great Britain on April 15, 1783.

The bell escaped a narrow brush with death in 1812 when Philadelphia officials considered demolishing the rotting hulk of the State House, which had lost its function since the state capital had moved inland to Harrisburg. But the city brokered a deal in 1816 to acquire the old State House, along with the bell, from the state. Eight years later, when the Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834) made his triumphal tour through the United States, the bell began to acquire a new life, largely through the publicity paid to the crumbling State House. Lafayette was received in a redecorated east room, where the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of 1787 had been signed, amidst massive celebrations and a new wave of interest in the revolutionary era. Now the State House, called Independence Hall, became hallowed ground. But the old bell still awaited its destiny.

That came in the 1830s when New York and Boston abolitionists, drawn by the bell’s inscription about proclaiming freedom throughout the land, appropriated the bell as an emblem of the growing campaign to abolish slavery. The New York Anti-Slavery Society’s Anti-Slavery Record named the “old bell,” as it was familiarly known in Philadelphia, as “The Liberty Bell”—“the tocsin of freedom and slavery’s knell,” as one abolitionist put it in a poem that was reprinted in the abolitionist paper The Liberator. The New York abolitionists egged on their Philadelphia counterparts, reminding them that “Hitherto, the bell has not obeyed the inscription and its peals have been a mockery, while one sixth of ‘all inhabitants’ are in abject slavery.”

1843: The Crack

After almost one hundred years of ringing in important commemorative moments, the Liberty Bell cracked in 1843. To this day many people believe the hoary legend that it cracked when tolling on July 8, 1835, as the funeral procession of John Marshall, longtime chief justice of the U. S. Supreme Court, passed through the city. It is almost certain, however, that the fissure occurred while it rang in remembrance of Washington’s birthday eight years later. Once damaged, it rested on the first floor of Independence Hall in elaborate settings.

The bell did not rest in the public’s admiration. In 1847, the journalist George Lippard (1822-1854) wrote a story, “Ring, Grandfather, Ring” for The Saturday Courier that related how an old bellman rang the bell to pronounce independence, after his grandson heard Congress’s resolve. The popular tale, though fictional, was retold as truth and thereafter linked the bell to the Declaration of Independence.

Once firmly fixed in the American mind as an avatar of all they believed their nation to be, the Liberty Bell was sent to and fro across the continent. After the Civil War, it became an important messenger of reconciliation between the North and South. Invited by the organizers of New Orleans’s World’s Industrial and Cotton Exposition in 1885, the bell, scrubbed and polished, was carried on an elaborately decorated flat car for a four-day trip to New Orleans. At each stop, people surged forward to touch, stroke, and kiss the bell as the train wended through Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi before finally reaching New Orleans. Once installed, it enthralled visitors for nearly five months, reaching iconic status. Once an antislavery symbol, it now became a symbol of national reconciliation, with its old antislavery message muffled in the process.

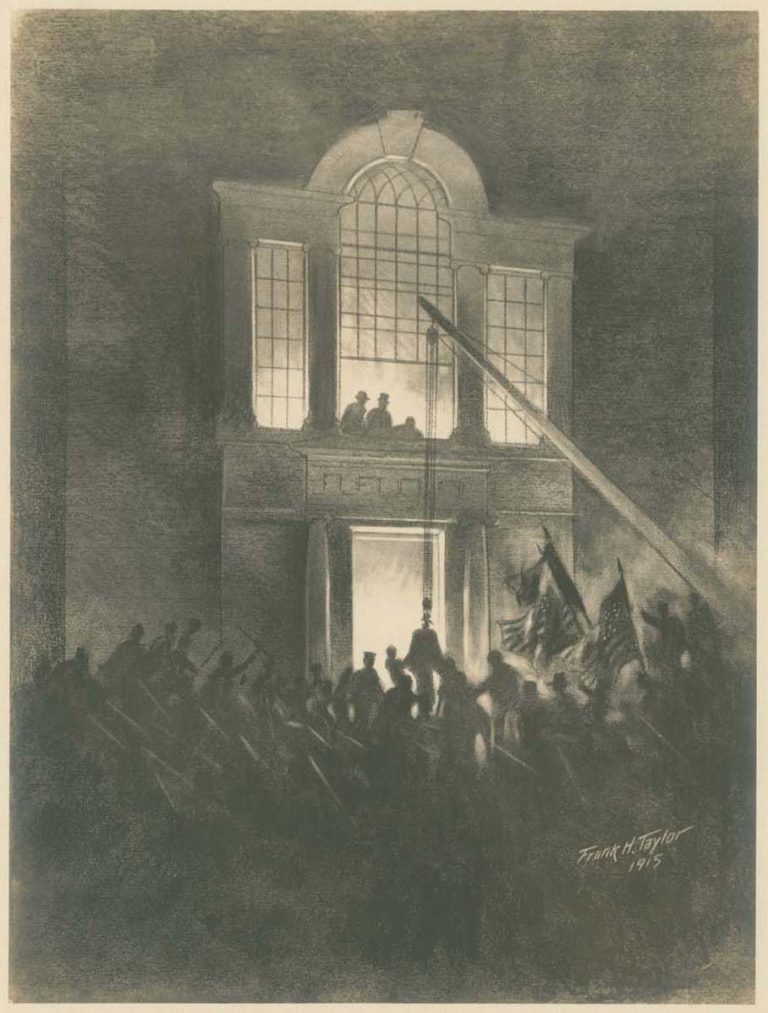

The next trip was to Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. On April 29, 1893, thirteen black horses with one hundred equestrial Chicago Hussars of the Illinois National Guard escorted the bell to the “White City”—the hundreds of building erected on the shore of Lake Michigan. The procession stretched for two miles “through crowds of enthusiastic people who cheered the Emblem of Liberty every step of the way—greater homage was never paid King or Queen,” wrote a Chicago newspaper. Most of some 27 million visitors gazed at the bell, displayed in the Pennsylvania building on a circular platform surrounded by a gilt railing built to keep at a distance the multitudes wanting to caress the bell. Shoals of visitors on July 4, 1893, drank in “The Liberty Bell March,” composed by America’s bandmaster John Philip Sousa (1854-1932). By the time of its return to Philadelphia in November 1893, about one-third of the nation had seen it. Flag worship had seized the country in an era of mass immigration, and bell worship now became its cousin. Other trips took the Liberty Bell to expositions in Atlanta, Charleston, St. Louis, and Boston.

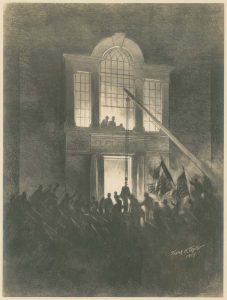

On the last of its seven trips, to San Francisco and San Diego in 1915, in the midst of a world set afire by World War I, a journalist in San Diego opined that “there is not a single person in any state of the union who does not feel a personal interest in the bell.” The historian of the Panama-Pacific Exposition echoed this: “The Bell is the great American patriotic symbol, almost a national Palladium. About that 20-odd hundred-weight of cracked metal there probably clings more of devotional feeling than about any other merely physical thing in the country.”

Never again would the Liberty Bell leave the city. The bell had accepted the laurels of an entire generation of Americans, and the nation’s school children had been taught–in poems, songs, and schoolbook stories–to revere the bell—a bell that belonged to everybody. Making it the indispensable American icon was the marketing of its image in millions of trinkets, postcards, miniature versions, postage stamps, and other memorabilia. On New Year’s Eve in 1924, 1925, and 1926, the tapping of the Liberty Bell, broadcast by radio across the nation, welcomed in the New Year. By this time, there was hardly a sensate American who did not know about the Liberty Bell.

The price of immortality was cooptation. Organizations of every political stripe and multiple causes enlisted the Liberty Bell for what they wanted. Among the first since the abolitionists were women suffragists. The Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association, campaigning amidst World War I, commissioned a Liberty Bell of their own to tour the state. Dubbing their bell the “Justice Bell,” they added two words to the famous inscription: the bell would not only proclaim liberty throughout the land but “establish justice,” which meant enfranchising women. Other groups followed their lead, including a citizens group called the Loyal Fraternity of the Liberty Bell formed to fight the resurgent Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, and the “Liberty Bell Ringers” in Michigan dedicated to keeping alive some of the unrealized Progressive reforms.

In both World War I and World War II, the U.S. government enlisted the Liberty Bell in “Liberty Bond” campaigns to finance the struggle to protect democracy. Ships and airplanes were named after the Liberty Bell, and the Liberty Bell itself, standing in Independence Hall, formed the backdrop for many patriotic gatherings. At President Franklin Roosevelt’s (1882-1945) urging, the bell was tapped for his radio broadcasts to pump up patriotism. The tapping went out over the radio waves throughout the war: tapping “V” for Victory in October 1942 to mark the thirty-first anniversary of the Chinese Republic; for “I am an American Day” on May 16, 1943; for July Fourth in the same year; for the opening of two new war bond drives in September 1943 and January 1944; for a recording to be played to the first wave of soldiers and marines storming the beaches of Normandy in June 1944; for the liberation of the Philippines on March 9, 1945; and tapping out VICTORY in August 1945. But while the United States fought a war in the name of freedom, African Americans recognized that the nation’s freedoms were not equally shared. In Philadelphia, Black banker Richard R. Wright Sr. (1855-1947) instituted an annual commemoration at the Liberty Bell to call attention to the continuing struggle for freedom and equality.

In the Cold War, Washington frequently deployed the Liberty Bell as the beacon demonstrating American unity and strength, while it was further immortalized when “Liberty Bell 7” carried Gus Grissom’s (1926-1967) into space in 1961. By this time, organizations from far right to far left claimed the Liberty Bell as their own. These ranged from the Liberty Belles, who saturated the country with messages that the Sixteenth Amendment (authorizing the federal income tax) was unconstitutional, to many organizations involved in the civil rights movement who staged sit-ins at the Liberty Bell, to members of the Quebec Separatist Movement that planned to dynamite the Liberty Bell in 1965, and to Earth Day environmentalists thronging the Liberty Bell on its first gathering in 1970. Meanwhile, entrepreneurs happily appropriated the Liberty Bell, plastering its image on everything from skimpy women’s underwear, to cat and dog pillows, to the gigantic image at the Phillies Citizens Bank Park that lights up and rings whenever a hometown baseball player hits a home run.

In 1976, to celebrate the Bicentennial of the American Revolution, the National Park Service (which assumed custodianship of the bell, along with Independence Hall, in 1948) moved the Liberty Bell from Independence Hall, where it had rested for more than two centuries, to a glass-and-brick pavilion facing Independence Hall a block away. Then in 2003 it found a new home in a spacious exhibit building at Sixth and Market Streets. This location, adjacent to the site where enslaved Africans labored in the household of President George Washington, forced a new reckoning over the legacies of freedom and enslavement in American history. Visitors to the Liberty Bell, numbering about 1.5 million annually in the early twenty-first century, encountered the bell’s long and varied history in exhibits as they moved toward the sacred bell, to be viewed but no longer touched.

Gary B. Nash is Professor of History Emeritus at UCLA and the author of many books, including First City: Philadelphia and the Forging of Historical Memory (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2010, University of Pennsylvania Press

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Liberty Bell Timeline (USHistory.org)

- Time Lapse, The Liberty Bell (NewsWorks)

- The Liberty Bell March (Library of Congress)

- George Lippard (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- For Teachers: The Liberty Bell, From Obscurity to Icon (National Park Service)

- The President's House (USHistory.org)

- Striking a Chord for Liberty (Hidden City Philadelphia)