Stadiums and Arenas

By Guian McKee | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

The stadiums and arenas of the Greater Philadelphia region provide a physical venue not only for athletic contests, but also for Philadelphians’ passionate connection to their sports teams. Deeply embedded in regional identity and personal memories, the history of the area’s stadiums and arenas reflects broad patterns of regional development and change.

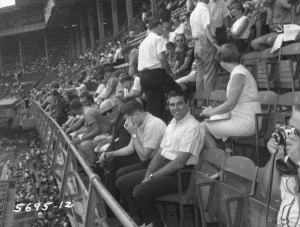

During the 1860s and 1870s, Philadelphia’s early professional baseball teams played in a variety of small, wooden structures scattered around the edges of Center City. In 1887, Phillies owner Alfred Reach (1840-1928) built a much more substantial stadium at Broad Street and Lehigh Avenue. Eventually known as the Baker Bowl, the new stadium originally seated 12,500 people and at one time featured a sloping bicycle track around the outfield. The Baker Bowl represented a major advance in stadium design, as its construction employed brick as well as wood. After an 1894 fire, the team expanded the facility, adding outfield bleachers and, in center field, team offices and a clubhouse with a swimming pool. The rebuilt stadium also featured baseball’s first cantilevered upper deck. Like other urban stadiums of its era, the Baker Bowl adapted to the built environment of the growing city: A Reading Railroad tunnel ran under center field, creating a small hill below the outfield wall. In addition, the stadium’s dimensions reflected the oddly shaped city lot on which it was built, as the right field foul line measured a short 280 feet, far less than left field. Notable disasters plagued the stadium, including a deadly balcony collapse in 1903 that killed twelve people and injured 232. A 1927 bleacher collapse, caused by rotting timbers in the aging stadium, led to a stampede in which one person died and fifty were injured. The Baker Bowl also hosted the Negro League Hilldale Daisies and the football Eagles, who played their first three seasons at the stadium, from 1933 to 1935. The Eagles’ tenancy in an outdated baseball stadium reflected professional football’s relatively low prominence among U.S. spectator sports before World War II.

In 1901, the new American League added a Philadelphia baseball team known as the Athletics. Owned by sporting goods manufacturer Benjamin Shibe (1838-1922) and led by manager Connie Mack (1862-1956), the team experienced almost immediate success. In 1909, the Athletics moved into a new stadium at Twenty-First Street and Lehigh Avenue. Shibe Park was the first stadium constructed entirely of steel and concrete. It seated 40,000. Historian Bruce Kuklick notes that the park also showed unprecedented attention to architectural detail for a sports stadium, with its “ornate facade in the French Renaissance style… rusticated bases, composite columns, arched windows and vaultings, and a domed tower.” Built in what were then the outskirts of North Philadelphia, the park relied on the streetcars that ran frequently along Broad Street and Lehigh Avenue to get fans to games. As neighborhoods of row houses and factories grew up around it, Shibe Park became deeply embedded in the dense urban fabric of the industrial city.

The Athletics gradually expanded Shibe Park so that by 1930 it featured upper decks along the foul lines and in left field. In 1938, the Phillies abandoned the decrepit Baker Bowl and became tenants of the Athletics at Shibe Park. They eventually purchased it from the struggling Athletics in 1954. The Negro League Philadelphia Stars also played Monday night games at Shibe Park, although their primary home was at the small ballpark at Forty-Fourth Street and Parkside Avenue in West Philadelphia.

Pro Sports, Local Identity

During the first half of the century, professional sports retained a local, even neighborhood identity. The Frankford Yellowjackets, a predecessor of the Eagles, were sponsored by the Frankford Athletic Association, a nonprofit community athletic organization that played its games at the tiny Frankford Stadium in the city’s Wissinoming section. The destruction of Frankford Stadium by arson in 1931 contributed to the team’s demise. Meanwhile, the intimate Philadelphia Arena on West Market Street hosted the city’s early hockey and basketball teams, such as the short-lived Philadelphia Quakers of the National Hockey League in 1930-31 and the Warriors of the National Basketball Association from 1946 to 1952.

The earliest hints of a shift away from such urban stadiums, however, had already appeared. After the Eagles left the Baker Bowl, they moved to Philadelphia Municipal Stadium in 1936. Built in far South Philadelphia for the 1926 sesquicentennial, Municipal Stadium was surrounded by parking lots and city dumps–a location completely unlike that of Shibe Park, and one that directly accommodated the automobile. Although the Eagles moved to Shibe Park in 1940, their brief tenancy far from the city center was a sign of things to come. Similarly, the Warriors left the Philadelphia Arena in 1952 for the larger and more modern Philadelphia Municipal, an arena located on the edge of the University of Pennsylvania campus in West Philadelphia.

The University of Pennsylvania itself built Franklin Field in 1895 to house its own athletic teams. Initially, the stadium consisted of a single, horseshoe-shaped deck, but in 1922 Penn added a second deck, raising the capacity to 80,000. The oldest college stadium in the United States, Franklin Field has hosted the Penn Relays track meet every April since 1895. The Eagles, after eighteen seasons at Shibe Park, moved to Franklin Field in 1958, winning their third NFL championship there in 1960. Penn’s basketball arena, the Palestra, was built in 1927–its name bestowed by a professor of Greek. The brick Palestra is small, intimate, and loud. It has been a main venue for Philadelphia’s intense high school and college basketball rivalries, featuring not only the traditional clashes of the local “Big 5” colleges but also numerous city high school championship games. Other important college basketball venues included Temple University’s McGonigle Hall, which opened in 1969 and played host to a series of national-caliber Temple teams before being replaced by the Liacouras Center (originally known as The Apollo of Temple) in 1997.

After World War II, suburbanization created new challenges for Philadelphia’s sports teams. Shibe Park, by then known as Connie Mack Stadium, seemed increasingly problematic as a professional sports venue. As white residents left for the suburbs, the surrounding area suffered from high rates of poverty as well as racial segregation and, increasingly, crime. Fans’ increased reliance on cars rather than mass transit created massive parking problems. After the Athletics departed for Kansas City in 1954 and the Eagles moved to Franklin Field in 1958, the Phillies were left as the sole occupants of a nearly fifty-year-old stadium that lacked modern amenities and sat in a neighborhood that many fans preferred to avoid.

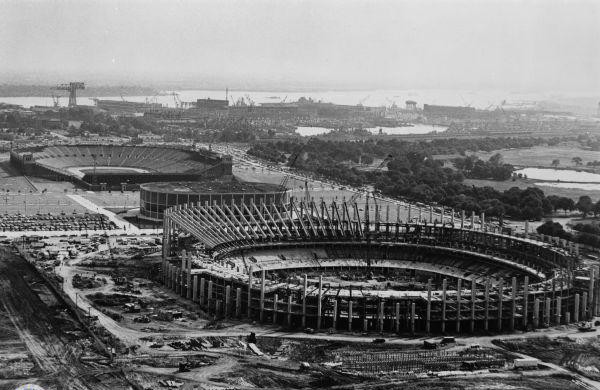

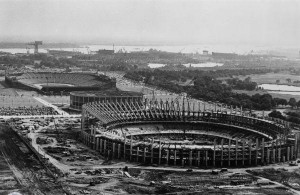

South Philadelphia Sports Complex

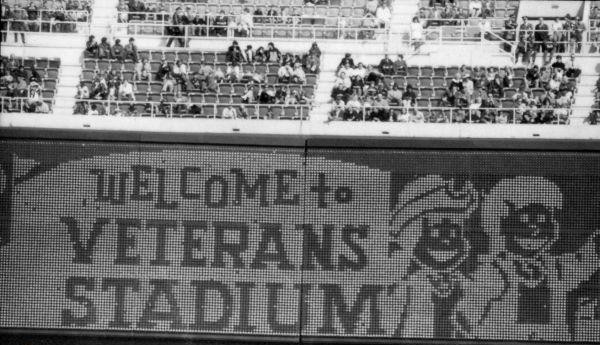

Consensus over where a new stadium should be located or who should pay for it proved difficult to reach. Stadium construction costs had increased dramatically, and neither the Phillies nor the Eagles possessed the capital to fund a new stadium privately. City leaders, however, remained hesitant to provide public funds. Eventually, after potential sites in Camden, in Torresdale, in Montgomery County, and in West Philadelphia above the 30th Street Station railroad yards all proved politically unworkable, the city, the Phillies, and the Eagles agreed on a site just north of Municipal Stadium in South Philadelphia. In 1964, Philadelphia voters narrowly approved a $25 million bond issue to fund a multisport stadium. As city and team officials debated design options, cost estimates rose again, requiring an additional $13 million bond issue in 1967. In 1971, following extensive delays and cost overruns, the Phillies and Eagles moved into Veterans Stadium, a fully enclosed, octorad-shaped structure that cost $65 million and initially seated 56,371 for baseball and 65,358 for football. As late as 2014, Philadelphia taxpayers were still paying off the bonds that had financed Veterans Stadium’s construction.

By the time “the Vet” opened, the Spectrum arena had been built across Pattison Avenue for the new Flyers hockey team and the 76ers basketball team. Along with Municipal Stadium (renamed in 1964 for President John F. Kennedy), the two new facilities created a sports complex that became the central focus for professional sports in the city. The complex’s expansive parking lots and location near interstate highways reflected the teams’ need to provide easy access for suburban fans reliant on the automobile. The location marked a stark contrast to that of earlier stadiums and arenas built in urban neighborhoods. Although neither building offered distinguished architecture, the move to South Philadelphia brought unprecedented on-field success, including championships for the Flyers in 1974 and 1975, the Phillies in 1980, and the 76ers in 1983, as well as a Super Bowl visit for the Eagles in 1981. The 700 level of the Vet became famous as the home of passionate and sometimes violent fans who gave the city its reputation as one of the most intense sports cities in the United States. The Vet and Spectrum also played host to a series of less-famous teams and events, including the Atoms, Fury, and Fever in professional soccer, the Stars of the United States Football League, the annual Army-Navy college football game (previously held at both Franklin Field and Municipal-JFK Stadium), and hundreds of concerts.

As the twentieth century came to a close, both facilities had become outdated. The opening of Baltimore’s Camden Yards baseball stadium started a move towards single-sport stadiums for both baseball and football, usually featuring luxury suites that could be lucratively leased to corporate customers. City leaders around the country began to see such facilities as a tool to promote economic growth and redevelopment, even though economists strongly disputed that claim. In 1996, the 76ers and Flyers moved into the $210 million CoreStates Center (subsequently known as the First Union, the Wachovia, then the Wells Fargo Center), built on the site of Municipal/JFK Stadium. Although the city paid the costs of local infrastructure for the project, most of the financing for the CoreStates Center came from Spectacor, the parent company of the Flyers (which in turn was soon purchased by the Comcast Corporation). Such private financing, however, had increasingly become an anachronism by the 1990s.

New Stadiums, Old Location

Around the United States, professional sports teams received generous public subsidies for new facilities despite widespread shortfalls in municipal budgets for basic city services. This trend soon extended to Philadelphia. Although the city’s business and political leaders initially resisted public financing, the state of Pennsylvania in 1999 agreed to contribute $200 million towards new stadiums for the Phillies and Eagles (part of a complex arrangement that also funded new stadiums in Pittsburgh). After a lengthy local debate, the city provided $300 million in additional subsidies for the stadiums. Private funding covered the remaining costs of the $1.01 billion project. In 2003, the Eagles moved into Lincoln Financial Field, just to the east of the Wells Fargo Center. The Phillies initially sought a downtown stadium, pushing for sites at Broad and Spring Garden Streets and in Chinatown, but opposition from nearby residents and businesses blocked both of these plans. Eventually, the Phillies agreed to remain in South Philadelphia and built Citizens Bank Park to the east of Veterans Stadium. The team played its last season at the Vet in 2003, and the thirty-three-year-old stadium was imploded the following March. The Spectrum remained in limited use until 2009, after which it too was demolished to make room for a new entertainment complex.

Meanwhile, a series of venues for other teams sprung up around the greater Philadelphia area. All of these facilities reflected the premise that sports could fuel economic development, and some have been used as tools for the attempted revival of the region’s most desperately poor communities. This trend began in 1993, with Wilmington’s construction of Daniel S. Frawley Stadium for the minor league Blue Rocks baseball team. Located along the Christina River on the former site of the Dravo Shipyard, the stadium served as an anchor for revitalization of the city’s “Riverfront District.” Built by the Delaware Stadium Corporation at a cost of $3.9 million in state and $2.2 million in city funds, it was followed by the construction nearby of a convention center and the creation of restaurants and other entertainment-oriented businesses. Following this model, Rutgers University joined with state and regional development authorities in 2001 to build a minor league baseball park in Camden (subsequently selling naming rights to Camden’s Campbell Soup Company). Offering spectacular views of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge and the Philadelphia skyline, the field became a popular destination along the revived waterfront of the otherwise still-struggling city. Finally, in Chester, the state of Pennsylvania and Delaware County provided $47 million in conjunction with private investment to build PPL Park, a soccer-only stadium for the Philadelphia Union. Like Frawley Stadium and Campbell’s Field, PPL Park formed the centerpiece of a waterfront-based revitalization effort. All of these facilities sought to appeal to fans throughout the wider region, especially in the suburbs. Whether in Wilmington, Chester, Camden, or South Philadelphia, however, stadiums did not prove to be reliable sources of broad-based economic development. Nearly all of the jobs that they created, either directly at the stadiums or in related commercial enterprises nearby, were part-time, low-wage service sector positions. Although the facilities drew people from throughout the region, they did not immediately provide an effective anchor for additional investment in surrounding, low-income neighborhoods.

For over a century, Philadelphia-area stadiums and arenas provided a core component of the region’s sports identity while also reflecting key characteristics of urban and regional development. From the early urban stadiums accessed by streetcars to modern multifacility complexes located amid acres of parking lots, decisions about the development of stadiums and arenas reflected the region’s changing economy, built environment, and transportation infrastructure. As economic stress increased in the region’s central cities, stadiums and arenas became part of a problematic revitalization strategy that strained public finances while providing benefits mostly for privately owned professional teams.

Guian McKee is Associate Professor of Public Policy at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center and Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy. He is the author of The Problem of Jobs: Liberalism, Race, and Deindustrialization in Philadelphia (Chicago, 2008), and he is the editor of three volumes of the Miller Center’s series The Presidential Recordings of Lyndon B. Johnson (published by W.W. Norton and The University of Virginia Press). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Stadium "delicacy" puts Chestnut Hill on the map (WHYY, December 28, 2010)

- Are new owners of Sixers hamstrung by renting the Wells Fargo Center? (WHYY, July 14, 2011)

- Winter Classic Alumni Game packs Citizens Bank Park seats with Flyers fans, mutual respect (WHYY, January 1, 2012)

- Eagles considering improvements to stadium (WHYY, June 19, 2012)

- Was building Camden's baseball stadium a mistake? (WHYY, April 1, 2014)

- International soccer event slated for Philly in July (WHYY, March 13, 2015)

- 123 years old and running strong, Penn Relays open Thursday (WHYY, April 27, 2017)

- Wells Fargo planning to drop name from South Philadelphia sports arena (6ABC via WHYY, July 24, 2024)

- After protesters removed from chambers, Philly Council votes 12-5 to approve Sixers' arena proposal (WHYY, November 19, 2024)

- Sixers will build new arena in South Philadelphia after deal reached with Comcast Spectacor (PlanPhilly/WHYY, January 13, 2025)