Toy Manufacturing

Essay

Philadelphia helped define the toy industry in the United States with simple yet engaging toys that became beloved by generations. Although social, cultural, and economic changes produced challenges for the industry, a few iconic toys stood the test of time and continued to promote imagination, creativity, and discovery for people of all ages.

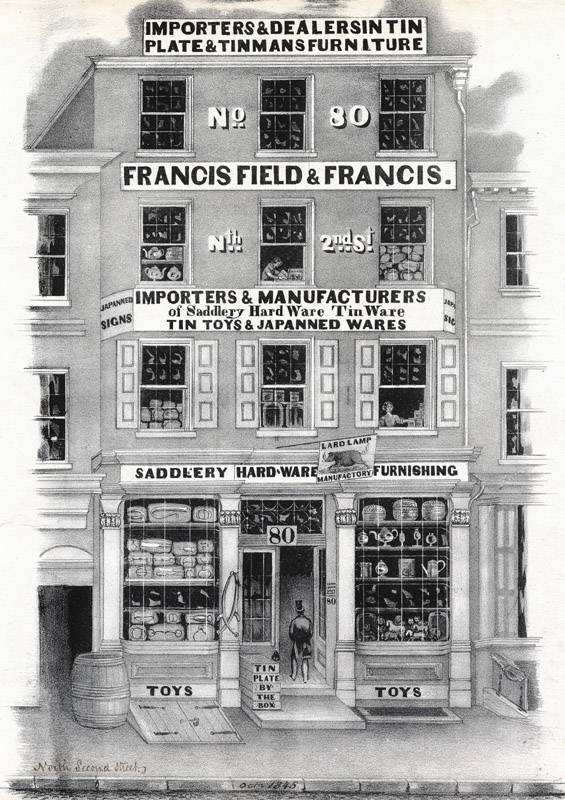

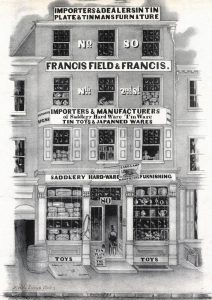

Philadelphia’s first toy manufacturer, among the first in the United States, opened in 1838 on North Second Street, between Race and Arch Streets. Francis, Field, and Francis, commonly known as the Philadelphia Tin Toy Manufactory, advertised imported French and German toys but also produced what is believed to be the first manufactured toy in the United States: a horse-drawn fire apparatus.

During the nineteenth century, as middle class prosperity grew, mechanical banks rose in popularity. The banks, like the “Boy on a Trapeze” bank made in Philadelphia by the J. Barton Smith Company, made the act of saving money fun for children. At the same time, designs often attracted adult interest with racial caricatures and political satire. A Philadelphia pattern maker, James H. Bowen (1877-1906), helped to make a Connecticut firm, J&E Stevens, the nation’s largest manufacturer of cast-iron toys in the country. The Stevens firm, based in Cromwell, Connecticut, originally sold hardware and a few iron toys but in 1869 manufactured its first cast-iron mechanical bank (Hall’s Excelsior). By 1890, the firm produced more than three hundred models, including Bowen designs such as “Darktown Battery,” “Girl Skipping Rope,” and “Reclining Chinaman.”

Toys by local manufacturers were among the products exhibited at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, hosted by Philadelphia in Fairmount Park. Honoring the birthplace of the nation, the Enterprise Manufacturing Company, a North Third Street firm specializing in coffee grinders, exhibited a mechanical bank in the form of Independence Hall. Another local manufacturer, James Fallows and Sons of North Second Street, displayed painted and stenciled tin horse-drawn wheeled vehicles, trains, and boats that judges commended for “economy in cost, adaptation to purpose intended, and durability.”

Albert Schoenhut’s Influence

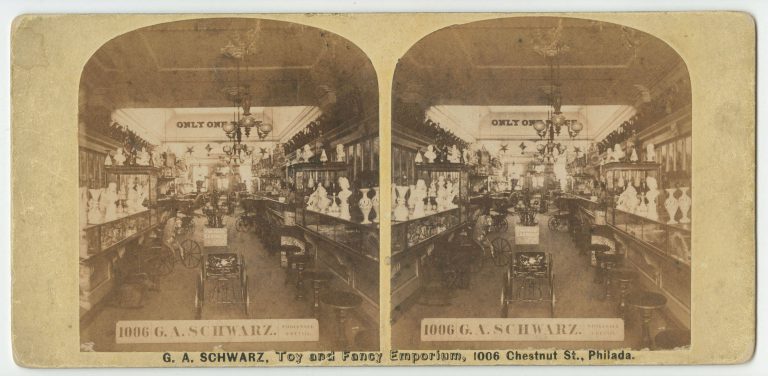

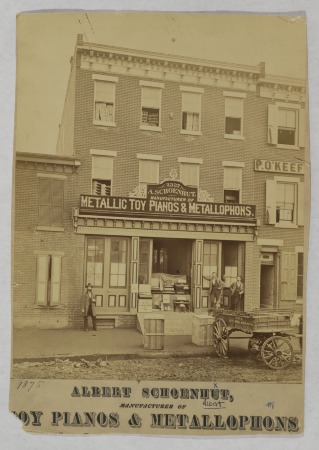

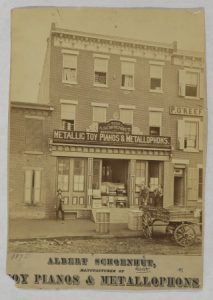

As cities and industries grew in the nineteenth century, mass production and department stores made an increasing array of toys more readily available for children and their families. Department store pioneer John Wanamaker (1838-1922), who sold miniature pianos and other toys, played a role in expanding local toy manufacturing in 1866 when he brought Albert Schoenhut (1849-1912) to Philadelphia to work at his store. From a family of German toymakers, Schoenhut was familiar with the manufacturing of miniature pianos and he fixed the broken glass bars by replacing them with metal ones. These new pianos had a craftsmanship that rivaled European manufacturers, making them a popular item for children in the Philadelphia area.

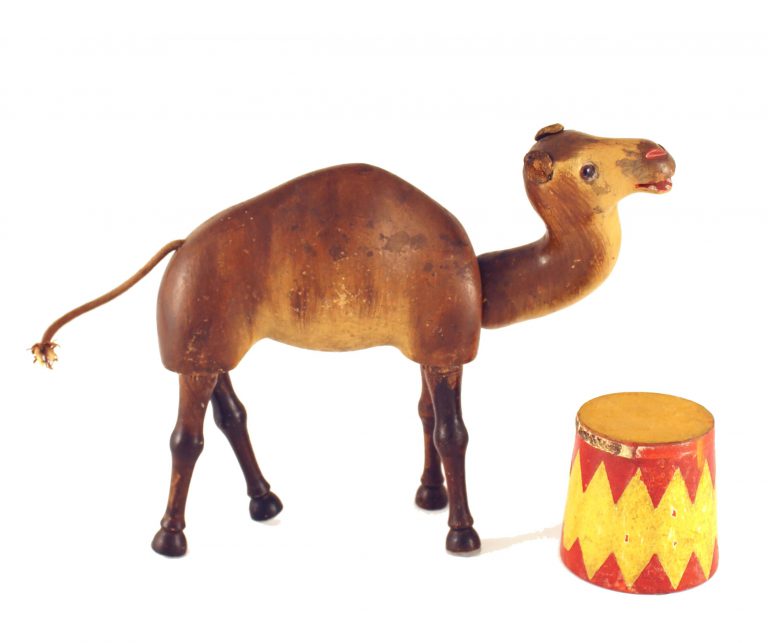

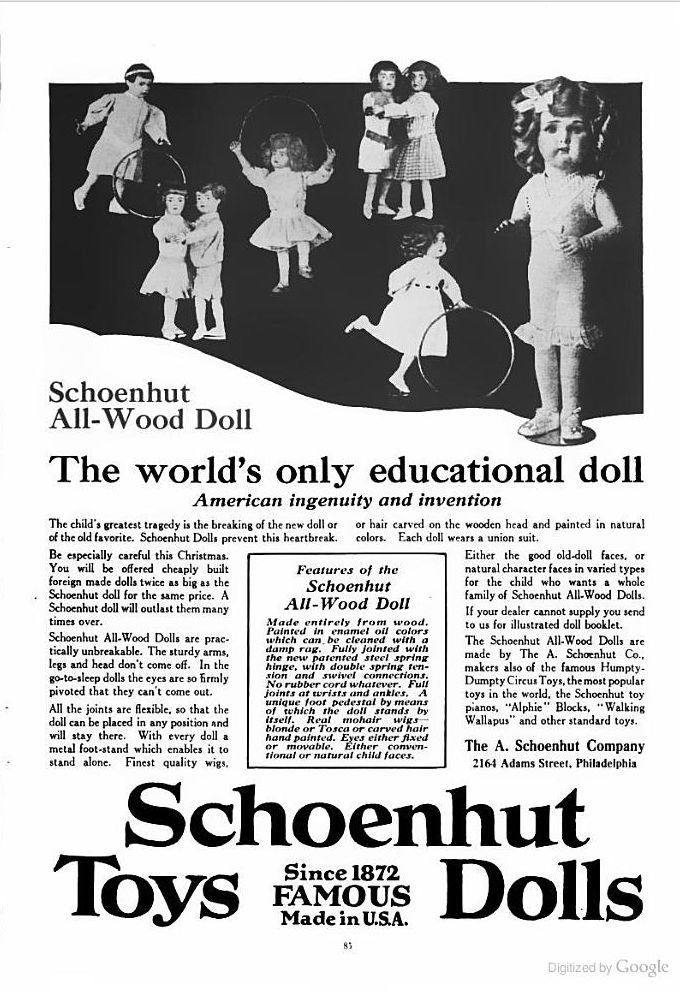

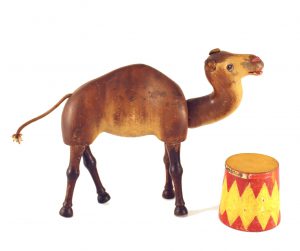

Recognizing the success of his pianos, Schoenhut opened his own storefront in 1872 on Frankford Avenue in Kensington and expanded his products. The company produced a variety of instruments, dolls, wooden dollhouses/furniture, and circus figures that promoted the power of play for childhood development. Around the turn of the century Schoenhut received a patent for clown figures and in 1903 began producing the popular “Humpty Dumpty Circus,” which quickly expanded to include thirty-seven animals, twenty-nine figures, and over forty accessories. By the time of Schoenhut’s death in 1912, the company was the largest toy manufacturer in the United States and the only to export to Germany, helping to build a longstanding reputation as the greatest American wooden-toy manufacturer.

Like other toy manufacturers, Schoenhut benefitted from a toy revolution that occurred as fewer families relied on children’s work for income. More children entered the creative world of play, creating increased consumer demand and growth for the domestic toy industry. World War I also opened a door for American manufacturing as turmoil in Europe cut off German exports to the United States, leading to record toy sales nationally for Christmas 1919. Increasing year-round demand led to the domestic toy industry producing more than $58 million worth of toys in 1925. In addition to Schoenhut, The Industrial Directory of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for 1922 listed Philadelphia contributors to the industry as Ad-Craft Inc., 305 Walnut Street, a maker of games and puzzles; the Philadelphia Game Manufacturing Company, 335 N. Third Street, whose products included a “Major League Baseball” board game; Elias Goodman, Howard and Palmer Streets; and Reeve and Mitchell Co., 1228 Cherry Street, a maker of wooden toys. The Pennsylvania Manufacturing Company in Hatfield, Montgomery County, also made wooden toys.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, however, toys became a luxury and sales dropped, forcing even the A. Schoenhut Co. into bankruptcy in 1935. An additional blow occurred during World War II, when materials previously used to make toys, especially iron, were diverted to war production. As a result of the wartime iron shortage, mechanical banks and other cast iron toys faded by 1950. Instead, similar items were made of tin by companies including J. Chein and Co., a New York-based company that opened a new factory in Burlington, New Jersey, in 1949. The Chein factory turned out banks, globes, sand pails, and other children’s items by the hundreds of thousands before turning to housewares in 1976 and then closing in 1992.

The Slinky Succeeds

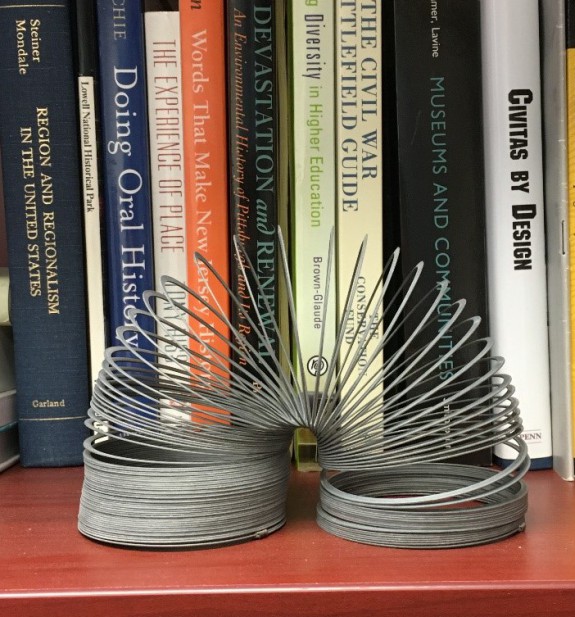

After World War II, Philadelphia became home to a new, iconic toy after a mechanical engineer at the Cramp Shipyard in Fishtown, Richard James (1914-74), discovered in 1943 that a device he was working on to keep equipment steady could “walk” off a shelf. Taking the idea home, after two years of experiments James invented the “Slinky,” a metal coil consisting of eighty feet of wire. By Christmas 1945 James and his wife, Betty (1918-2008), spent $500 to manufacture their new toy to be sold at Gimbels department store. At $1 each, all four hundred Slinkys sold almost instantly. Manufactured in Philadelphia until 1964, the company then moved to Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania, where it continued to produce more than 250 million Slinkys a year.

As product demands grew during the years of the post-World War II baby boom, new manufacturing techniques increased production and decreased production costs. Scale models of airplanes, boats, military vehicles, and trains became popular, and Bachmann Trains on East Erie Avenue used an injection mold technique to produce and debut the Plasticville U.S.A. line in 1947. Bachmann, a firm founded in Philadelphia in 1833 as a manufacturer of hair ornaments, became one of the leading manufacturers for scale-model buildings used on train layouts, adding a variety of buildings to the product line through 1958. By 1963, after slot cars became more popular and the market for model trains decreased, Bachmann introduced a line of slot car accessories. By the mid-1980s, with domestic manufacturing fading, Bachmann was bought by Hong Kong-based Kader Industries, which moved the manufacturing line to China.

Most toy manufacturing in the United States moved overseas in the late twentieth century, but the Philadelphia area also gained a local toy maker in the 1990s. After fidgeting with disposable straws at a wedding in 1990, Joel Glickman (b. 1940) created K’Nex, a building set of rods and connectors that later expanded to include gears, blocks, and wheels. Made in Hatfield, Pennsylvania, by the Rodon Group, more than 39 billion flexible plastic K’Nex pieces were produced beginning in 1992. In 2016, K’Nex formed a holding company, Smart Brands International Co., to build its business globally.

Although the Philadelphia region had a limited presence in the industry by the twenty-first century, its toy legacy remained available for new generations in museums such as the Please Touch Museum in Fairmount Park and the Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent in Center City. These toys remained some of the most iconic in the world with long-lasting influence on the industry.

Amanda Sherry is a museum professional in the greater Philadelphia region. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Flexible Flyer Factory Glides Into Obscurity (Hidden City)

- The slinky, civil engineer Richard P. James of Philadelphia (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Albert Schoenhut and Company (Workshop of the World)

- Bachmann Trains

- Toy World at the New Jersey State Museum (YouTube)

- Seven Decades of J. Chein & Co. Toys (Antiques and the Arts Weekly, 2008)