Capital of the United States (Selection of Philadelphia)

Essay

As the national capital from 1790 to 1800, Philadelphia was the seat of the federal government for a short but crucial time in the new nation’s history. How and why Congress selected Philadelphia as the temporary Unites States capital reflects the essential debates of the era, particularly the balance of power between North and South. These debates, as well as the creation of new national institutions and the rise of political parties, defined Philadelphia’s decade as the capital city and created an enduring connection to the early national period.

Philadelphia’s selection in 1790 as the temporary national capital followed the drafting of the new federal Constitution, which authorized Congress to enact legislation for the establishment of a permanent seat of government. After departing Philadelphia in 1783, Congress convened in cities as varied Princeton, New Jersey; Lancaster, Pennsylvania; and Baltimore, Maryland, before settling in New York in 1785. As a candidate for the permanent capital, Philadelphia’s size, wealth, and central location weighed in its favor, yet congressmen from both New England and the Southern states considered

Philadelphia too urban, as well as hot and prone to outbreaks of disease. By and large, sectional conflicts and whether or not the capital should be a commercial city animated the debate and guided Congress’ efforts to find a location “consistent with convenience to the navigation of the Atlantic Ocean, and having due regard to the particular situation of the Western Country.”

Western Contenders

Indeed, the perceived need to secure the ever-expanding western frontier against foreign foes and indigenous independence movements keenly influenced the location of the permanent federal capital. Whereas in 1783 all proposed sites hugged tidewater or lay slightly inland, by 1787 most contenders were farther west, including Lancaster; Carlisle, Pennsylvania; and Fredericksburg, Virginia, as well as a tract of land on the Potomac jointly offered by Maryland and Virginia. Western expansion similarly informed the contest between North and South to secure the capital, as each region adopted a different geographic calculus to advance its case. While Northern advocates focused on current population centers, placing the city east of Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna River, Southern promoters emphasized future growth and the implicit and unstated elevation of the agrarian, slave-based economy from minority to majority status. Notably, both sides assumed a natural alliance between Southern and Western political interests, a crucial consideration given the capital’s potential to enhance the power and leverage of the region in which it was located.

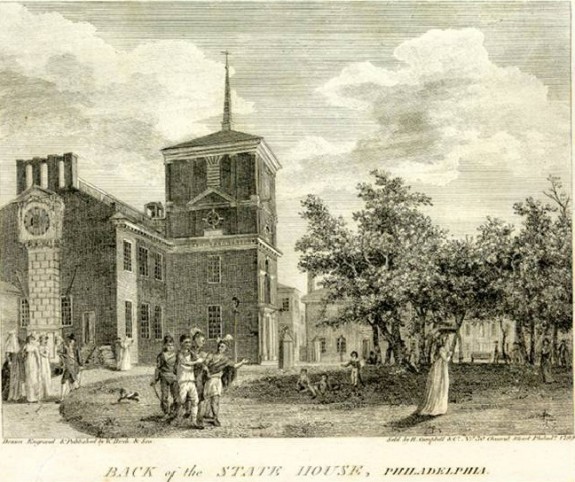

By 1790, two dozen sites, located on or near the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, the Susquehanna, the Chesapeake, and the Potomac, had been proposed publicly as candidates for the capital city. The Philadelphia region figured prominently in several proposals, which alternately incorporated portions of Southwark, Northern Liberties, Byberry, and Germantown. Several prominent Philadelphians, including Tench Coxe (1755-1824), Robert Morris (1734-1806), and Dr. Benjamin Rush (1746-1813), lobbied on the city’s behalf, with Morris going so far as to offer his mansion on High Street as the presidential residence. For their part, Philadelphia’s citizens flooded Congress with petitions and the City Council pledged money for both remodeled federal housing and public buildings, including a new city hall and a courthouse built on the same square as the existing Pennsylvania State House.

Ultimately, the issue of assumption, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton’s (1757-1804) plan for the federal government to assume the states’ war debts, determined the capital’s permanent location. Facing resistance from states like Virginia that had already resolved their debts, Hamilton wedded the questions of assumption and the federal capital together in hopes of striking a political bargain that advanced his cause. While Robert Morris negotiated with Hamilton to establish the capital in Germantown or at the Falls of the Delaware, a deal never came to fruition. Instead, wary of Virginia’s opposition to the assumption plan, Hamilton struck a deal with Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) that provided enough Northern votes for a federal capital on the Potomac. In exchange for the Pennsylvania delegation’s support, Coxe and Morris negotiated a plan to relocate the capital from New York to Philadelphia for ten years. The final compromise, the Residence Act of 1790, passed both houses of Congress in July 1790.

Skepticism Over a Capital on the Potomac

As New Yorkers decried the loss of the capital, Philadelphians embraced the city’s status as the temporary capital and hoped that, once the federal government settled in Philadelphia, inertia would keep it there permanently. While the Potomac seemed best situated to strengthen and preserve the connection between the North, South, and West, many were skeptical that a new capital constructed out of so-called “wilderness” was preferable to the nation’s largest city. As one Baltimore newspaper argued, the “idea of fixing their Residence in the Woods, can only be agreeable to a Congress of hermits.” A Connecticut humorist similarly proposed a constitutional amendment banning Congress from establishing itself “in an Indian wigwam …[or] in the howling wilderness.” Nonetheless, under the leadership of President George Washington (1732-99), plans for a Potomac capital continued apace as Congress reconvened in Philadelphia.

In December 1790, Philadelphia stretched approximately nine blocks north and south along the Delaware River. Per the first federal census, the population of the city and its adjacent districts was 42,520 inhabitants. While the United States Supreme Court occupied City Hall, the House of Representatives and Senate convened in what became known as Congress Hall, a Philadelphia County courthouse recently erected just west of the State House. Over the ensuing decade, these walls bore witness to several key events in the nation’s formative period, including the ratification of the Bill of Rights and Jay’s Treaty, President John Adams’ inauguration, and the passage of both the federal Fugitive Slave Act and the Alien and Sedition Acts. Congress also passed legislation to establish the First Bank of the United States, the U.S. Mint, and the federal tariff, thereby enacting Secretary Hamilton’s plan to create the nation’s first financial center and spur maritime commerce and commercial growth.

As the federal capital, Philadelphia boasted a diverse population that included foreign dignitaries, representatives of many Indian peoples, and a significant free Black community, all of whom animated its political culture and enhanced the city’s reputation as the most cosmopolitan city in the new republic. The concentration of government activity around Sixth and Chestnut Streets notably afforded constituents easy, daily access to their representatives and increased Philadelphians’ political participation to levels unmatched over the next century. Between 1790 and 1800, Philadelphia’s elections were watched for signs of national political developments, most critically Federalists’ declining support and the rise of a two-party system. The growth of partisan politics was likewise evident in the city’s print culture, especially newspapers like the Aurora and Gazette of the United States that increasingly aligned with either the Federalist or Jeffersonian factions. As the federal government prepared to depart Philadelphia in 1800, change was on the horizon for both the nation and the city, whose loss of the federal capital arguably marked the end of its role as the preeminent American metropolis. Nonetheless, the legacy of Philadelphia’s tenure as the national capital endures in the national institutions that first took root in Philadelphia and whose physical presence provides a boon for historical tourism and a trademark of civic identity.

Hillary S. Kativa received her B.A. in History and English from Dickinson College (2005) and her M.A. in History from Villanova University (2008). Her research interests include American political history and presidential campaigns, public history, and digital humanities. (Author information current at time of publication)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University