Cold War

Essay

The period of international political and military tension known as the Cold War (1947-91) had military, political, and cultural implications for Greater Philadelphia. The region served as a first line of defense for a conflict that depended more on missiles than forts, and it provided the nation with an arsenal, a shipyard, and a source of manpower. While a direct military confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States, the Cold War’s principal adversaries, failed to materialize, the conflict made its mark on the region in other ways, including anti-communist suspicion, civil defense, and the 1967 summit between President Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-73) and Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin (1904-80) in Glassboro, New Jersey.

The Cold War emerged after World War II when the United States and the Soviet Union—wartime allies against Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy—reverted to their prewar ideological rivalry between U.S. promotion of capitalism and Soviet support for Communist revolutions. As early as 1946, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965) described the postwar divide in Europe as an Iron Curtain. In 1961 the East German government constructed the Berlin Wall, physically dividing the city and symbolic of Cold War tension. While the Soviet Union and the United States avoided direct military conflict, each became involved in proxy wars around the world, most notably in Korea (1950-53), Vietnam (1950-75), and Afghanistan (1979-89). Each nation worked to expand its international influence in a conflict carried out through propaganda, espionage, domestic surveillance, soft power (economic and cultural), the space race, and the threat of atomic weaponry. While Cold War tensions eased during the 1970s, a period characterized by détente (thawing), they resumed following the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979.

Into the Postwar World

At the end of World War II, Philadelphia stood as America’s third largest city. Optimism ran high amid military demobilization and the lapsing of wartime rationing and restrictions. A building boom took place, and rows of small houses and garden apartments appeared in the city’s sections of East Germantown, West Oak Lane, and the Northeast. Philadelphia’s colleges and universities grew markedly in enrollment due to the educational opportunities made possible for veterans under the G.I. Bill.

At the same time, however, apprehension grew over the detrimental impact of the sudden peace on local defense operations and industry. These fears quickly became realized at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, where fifty-eight ships were deactivated by the middle of 1946. The Navy Yard laid off thousands of civilian workers and cut naval personnel from 345 officers and 639 WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) in 1945 to 82 officers and 172 WAVES in 1949. To assist laid-off workers in finding employment, the Navy Yard established a Reduction-in-Force Unit in its Industrial Relations Division.

Postwar cuts generated constant fear of base and shipyard closure. In 1949, the Harry S. Truman (1884-1972) presidential administration laid off more than four thousand government employees at the Frankford Arsenal, Marine Corps Supply Depot, Naval Home, Quartermaster General Depot, and Signal Corps Stock Control Office, reducing the federal payroll in Philadelphia by $13 million. It further closed the Atlantic City Naval Air Station at Pomona, New Jersey, and announced plans to reduce the authorized number of personnel at the Navy Yard from nine thousand to seven thousand.

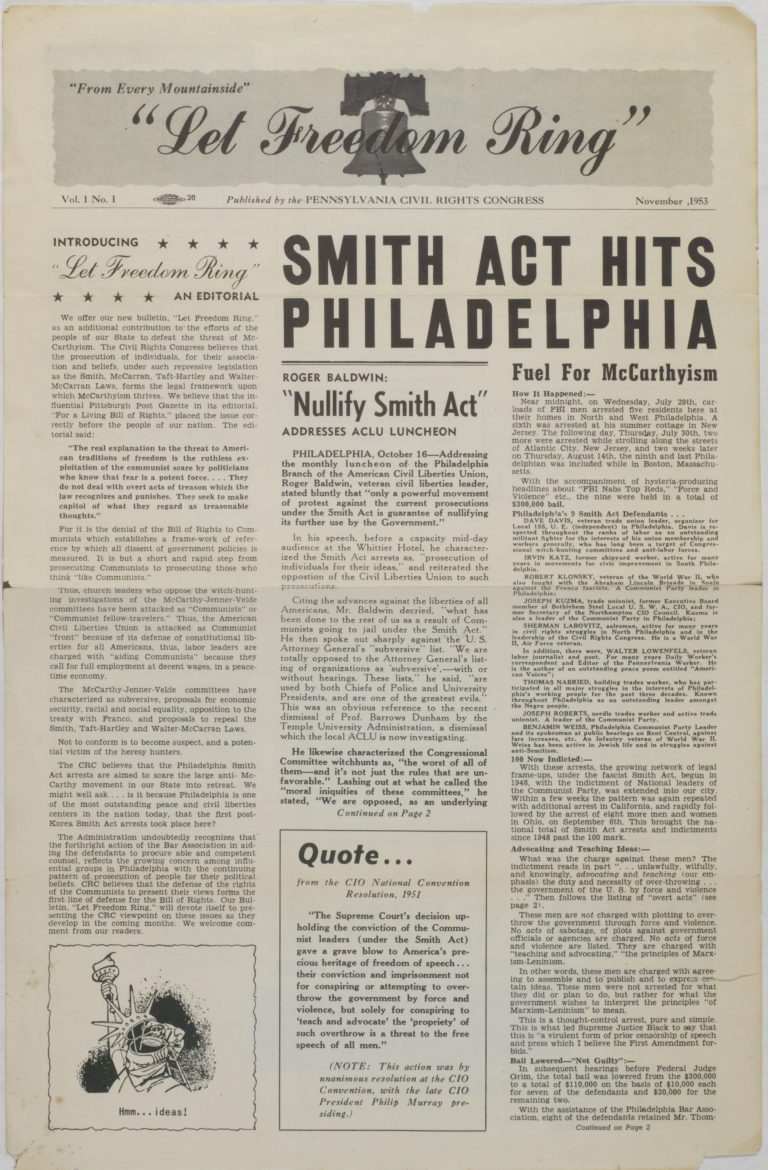

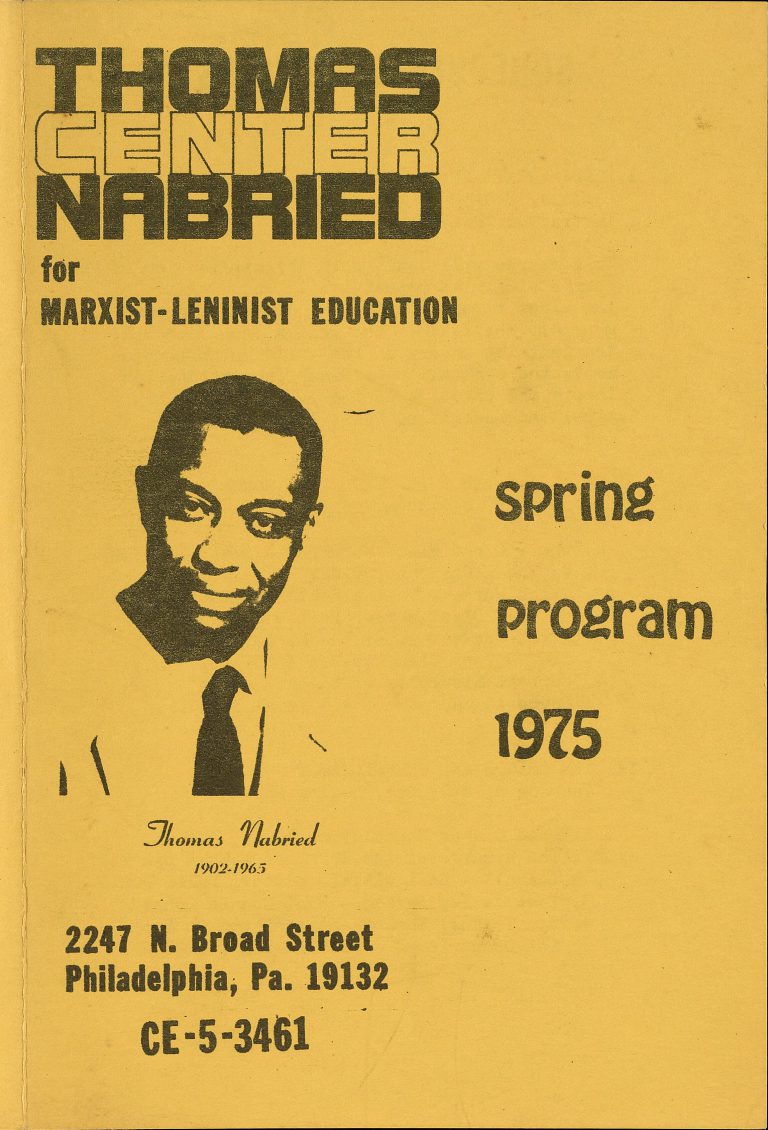

In addition to the military cutbacks, the spectre of communism provoked anxiety as political leaders, the media, and others warned of domestic threats. The Communist Party already had a strong presence in the region. Its membership of nearly one hundred thousand individuals by the late 1940s owed to both the economic toll of the Great Depression and the U.S.-Soviet alliance during World War II. During the postwar period, Communists built on existing racial tensions to recruit African Americans. The party’s newspaper, The Daily Worker, regularly reported instances of police brutality and frame-ups directed against African Americans in Philadelphia. Thomas Nabried (1900-65), the party’s city chair (1942-45) and then district chair for eastern Pennsylvania and Delaware, worked to organize fellow African Americans in the city and throughout Bucks County. By the 1950s, African Americans came to constitute more than one-sixth of the party’s membership. The party’s strength, however, proved short lived, as it failed to withstand the anti-communist mood of the 1950s and ceased to operate as an effective political force.

Veterans organizations emerged early as forceful proponents of anticommunism. The Catholic War Veterans, for example, organized mass demonstrations in Philadelphia in December 1946 to protest the repression of the Catholic Church in communist Eastern Europe. The Pennsylvania American Legion expressed support for the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the McCarran Act, a 1950 federal law that called for the registration of “subversives.” Veterans groups sponsored patriotic celebrations such as Loyalty Day, designated by President Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969) in 1958 and held annually on or near May 1.

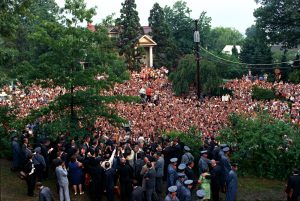

Patriotic activities to celebrate the United States, including the role Philadelphia played in its founding, accompanied anticommunist initiatives throughout the Cold War. Religious leaders played an important role. Vito Mazzone (1903-85), pastor of St. Mary Magdalene de Pazzi at 712 Montrose Street in South Philadelphia, encouraged active patriotism among his parishioners. “Christian patriotism” was the message of evangelist Billy Graham (b. 1918), who attracted a crowd of nearly seven hundred thousand to his Philadelphia crusade in 1961. Philadelphia served as the point of departure for the Freedom Train, which carried an exhibit of the nation’s founding documents around the country between 1947 and 1949. The era’s heightened patriotism also brought increasing numbers of tourists to see Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell, which became the centerpieces of Independence National Historical Park, authorized by Congress in 1948.

Military Revitalization and Nuclear Threats

The Cold War suddenly turned hot in June 1950, when North Korea invaded South Korea. This followed the Soviet Union’s first explosion of an atomic bomb and the creation of the Communist Peoples Republic of China. The Philadelphia region felt the impact as jobs returned to the Naval Yard. At the height of the American-led United Nations “police action” in Korea at the end of 1951, 14,750 went to work for the Navy in the shipyard. A new Radiological Decontamination Training Facility opened in Building 681 and distributed manuals for ship decontamination in the event of an air burst of atomic bombs.

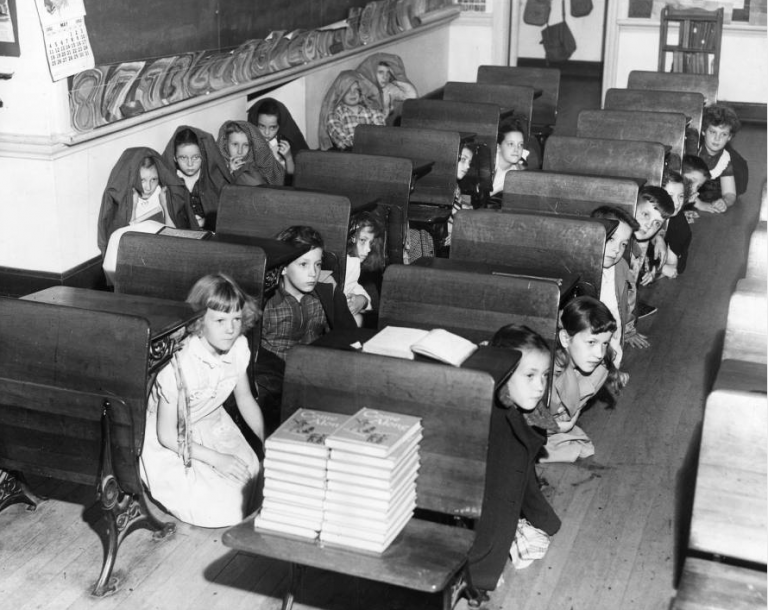

The fear of nuclear attack remained paramount. In 1952, Pennsylvania’s Civil Air Patrol dropped leaflets in Bucks and Chester Counties that warned of potential bombs. By the 1950s, the Philadelphia District of the Corps of Engineers supervised construction of twelve NIKE/AJAX surface-to-air missile sites averaging twenty-five miles from Center City. Regular Army and Pennsylvania National Guard manned the batteries with command and control functions located at a facility in Pedricktown, Salem County, New Jersey. Missile sites in New Jersey protected the New York area in the north and the Philadelphia area in the south.

As nuclear espionage dominated national news, in May 1950 authorities arrested a South Philadelphia man, Harry Gold (1910-72), on espionage charges. A South Philadelphia High School graduate, Gold had studied chemical engineering at Drexel Institute and by the 1930s had begun to provide the Soviets with documents about industrial solvents and manufacturing processes from the Pennsylvania Sugar Company, the Fishtown refinery where he worked. At that time one of the largest sugar refineries in the world, Pennsylvania Sugar had subsidiaries that produced everything from Quaker brand antifreeze to solvents, lacquers, and rum.

Following his arrest, Gold confessed to acting as a courier to pass information for the Soviets about the Manhattan Project, which produced the atomic bomb, to atomic spy Klaus Fuchs (1911-88). This led to the arrest of David Greenglass (1922-2014), a Manhattan Project machinist whose testimony resulted in the espionage arrest, trial and execution of Greenglass’s sister Ethel Rosenberg (1915-53) and her husband, Julius (1918-53). Gold served fifteen years of the thirty-year sentence he received before his parole from the Federal Penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, in May 1966.

Reflecting continuing anxiety about Communist activity within the United States, organizers of Pennsylvania Week activities in 1951 chose “Defense” as their theme. Philadelphia’s Civil Defense Council, citing a shipment of purported sabotage manuals allegedly unloaded from a ship at the Philadelphia docks, warned of the need to detect subversive threats. The region’s desire to expose potential communist subversives manifested in the adoption of statewide loyalty oaths in Pennsylvania (1951) and New Jersey (1949). Delaware remained one of only seven states to resist adopting such legislation. Locally, meanwhile, in 1955 the Philadelphia School District dismissed twenty-six teachers for refusing to answer questions about Communist affiliations on the basis of their rights under the Fifth Amendment. In the suburbs, the Bucks County Bar rejected an applicant based on his association with a Marxist fellow student at the Pennsylvania State University. An appeal eventually overturned the decision.

The Cold War elevated the importance of universities to national security. As centers of scientific production, the federal government provided campuses with unprecedented funding. Philadelphia’s campuses benefited from the Section 112 program, a 1959 revision to the Housing Act that responded to the Soviet Union’s launch of its satellite Sputnik two years before. This enabled urban universities in selected cities, including Philadelphia, to undertake massive expansion projects at little or no cost to the universities.

Because of their perceived importance and the federal dollars they received, universities came under the scrutiny of authorities early and often. Barrows Dunham (1905-95), professor of philosophy and department head at Temple University, attracted interest from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) because of his former membership in the Communist Party. Subpoenaed to appear before the U.S. House Un-American Affairs Committee in October 1952, Dunham ultimately sought protection under the Fifth Amendment and refused to answer questions. Cited for standing in contempt of Congress in May 1954, Dunham secured an acquittal a year later. Temple officials dismissed Dunham and continued to cooperate with the FBI. In July 1981 Temple’s trustees acknowledged Dunham’s dismissal as an error and reinstated him as professor emeritus entitled to a lifetime pension.

The Cold War further revitalized the Philadelphia Naval Yard during the Vietnam War, when the facility entered its most active period of operations and highest level of employment since World War II. Its annual payroll reached nearly $90 million. Activity diminished after Vietnam, but the Naval Base remained vital to national defense throughout the Cold War. Most notably, the Jimmy Carter (b. 1924) presidential administration awarded Philadelphia $500 million to fulfill the first Carrier Service Life Extension Program (SLEP) contract for the 60,000-ton attack carrier Saratoga. Continued SLEP contracts employed thousands of Delaware Valley residents and brought hundreds of millions of dollars to the region over the next twenty years.

The Cold War’s costs included the men and women overseas to serve in the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Draftees and volunteers from across the northeastern United States reported to Fort Dix in New Jersey for basic training. Many did not return. The Korean War exacted a human toll of over six hundred dead from Philadelphia and its surrounding counties. Forty-three from Delaware died in Korea while nearly eight hundred from New Jersey lost their lives. The war in Vietnam proved even more costly, as 646 Philadelphians, 122 service people from Delaware, and 1,500 from New Jersey never returned from Vietnam.

These costs rendered the Vietnam War increasingly divisive at home. The conflict shattered the Cold War consensus as supporters and protestors demonstrated on college campuses and sought claim to Philadelphia’s symbols of America’s democracy, including the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall. Following two years of acrimony on its campus, the University of Pennsylvania terminated its chemical and biological warfare contracts with the Pentagon.

Crossing the Divide

The accelerated globalization that accompanied the Cold War brought issues of national security to doorsteps across the nation. For those in the Philadelphia region, as for others across the United States, this rendered a renewed focus on home and family life that increasingly transpired in the suburbs. At the same time, Philadelphia became more connected to the world. In 1945, the United States Air Force returned Philadelphia Municipal Airport to civil control after using it as an airfield during World War II. It became Philadelphia International Airport later that year when American Overseas Airlines began direct flights to Europe. This coincided with the city proposing that Philadelphia become the permanent home for the newly established United Nations, offering a ten-square-mile site on Belmont Plateau but losing the bid to New York.

While often engulfed in Cold War tensions, Philadelphians also sought ways to alleviate them. In 1958, the Philadelphia Orchestra departed for its first tour of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. In 1973, the orchestra embarked on another first, a trip to the Peoples Republic of China that preceded the existence of an American embassy in Beijing. This type of exchange also extended to sport. In July 1959, Philadelphia hosted the first in a series of track meets between American and Soviet athletes at the University of Pennsylvania’s Franklin Field. While Soviet athletes largely prevailed over their American counterparts, almost twenty years later the defending Stanley Cup champion Philadelphia Flyers scored a convincing 4-1 victory over Moscow’s Central Hockey Club at the Spectrum on January 11, 1976.

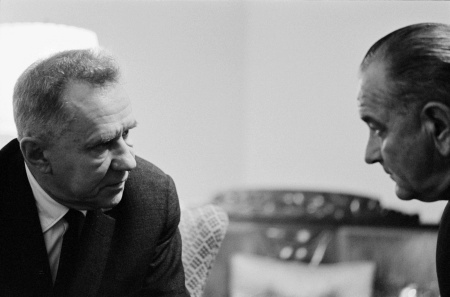

The region also offered the site for the 1967 summit meeting between President Johnson and Soviet Premier Kosygin. The two met June 23-24 at Hollybush Mansion, the residence of Glassboro State College (Rowan University) President Thomas E. Robinson (1905-92). The choice of site, with only two day’s notice, derived from a disagreement about whether the meeting should take place in Washington or in New York, where Kosygin was attending an emergency United Nations Security Council meeting to discuss the recently concluded Six Day War.

Both sides agreed on Glassboro, located exactly at the midpoint between New York and Washington. Johnson considered the site ideal for its relatively rural location, removed from the growing protests on Philadelphia’s campuses against the Vietnam War. The summit failed to produce any agreements, notably on the limitation of anti-ballistic missile systems. Limited headway made by the two leaders on the terms of a nonproliferation treaty failed to result in the issuing of any communique, and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 delayed further serious discussion between American and Soviet officials until 1972. However, the Glassboro meeting’s spontaneity and its spirit of cooperation resonated widely at the time. This helped pave the way for a period of thawed relations between the Cold War adversaries referred to as détente.

Philadelphia continued to serve as an important site for the nation’s expression of patriotism. As the Cold War varied in intensity, the city hosted America’s Bicentennial celebration in 1976 and the bicentennial anniversary of the Constitution in 1987. It also rewarded the pursuit of freedom globally, awarding the inaugural Liberty Medal in 1989 to Lech Walesa (b. 1943) of Poland, the leader of Solidarity, the Soviet bloc’s first independent trade union.

The Cold War concluded in 1991 with the internal collapse of the Soviet Union. The tensions of the era served to revitalize the military establishment in Greater Philadelphia, injecting the economy with money and jobs. The cost, however, included an anticommunist hysteria that occurred throughout the nation. Thousands of area residents lost their lives in Cold War-era military conflicts. While the region contributed markedly to the nation’s defense, through its missile defense initiative and operations at the Philadelphia Naval Yard, its sacrifices proved more substantial.

Robert J. Kodosky is an Associate Professor of History at West Chester University. He is the author of Psychological Operations American Style: The Joint United States Public Affairs Office, Vietnam and Beyond.

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

National History Day Resources

- Thomas Nabried Center for Marxist-Leninist Education (Yale University Libraries)

- FBI Arrests Six Pennsylvania Red Leaders (Chicago Tribune Archives)

- The Atomic Archive

- Barrows Dunham Manuscripts (Princeton University Library)

- he Chance for Peace, speech by Dwight D. Eisenhower, April 16th 1953 (Explore PA History)

- Let Freedom Ring, November 1953 - Smith Acts Hit Philadelphia (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- United States of America v. Joseph Kuzma, Joseph Roberts, Benjamin Weiss, David Davis, Thomas Nabried, Irvin Katz, Walter Lowenfels, Sherman Marion Labovitz, Robert Klonsky, Appellants, 249 F.2d 619 (3d Cir. 1957)