Northeast Philadelphia

Essay

From its initial, colonial foundations as a sparsely populated farming hinterland to its dramatic postwar housing development after World War II, Northeast Philadelphia developed into a desirable destination for those seeking to improve their economic, social, and cultural standing within Philadelphia’s city boundaries. Even as Northeast Philadelphia came to symbolize a middle-class environment rooted around homeownership, commercial development, and mass affluence following World War II, it spurred acrimonious racial tensions between white and Black residents and confronted city politicians and policy makers about local concerns related to zoning, commercial, and municipal services. Stretching from Frankford in the lower Northeast to Somerton in the Far Northeast, its vast geographic expanse underwent dramatic spatial, economic, and racial transformations throughout its complex and still unfolding history.

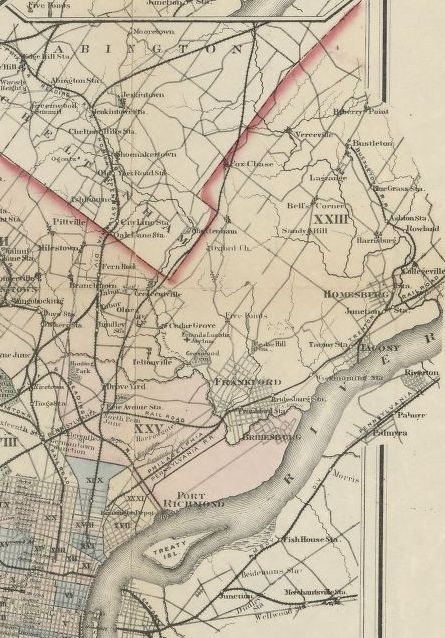

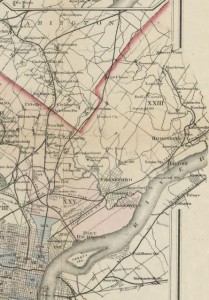

Northeast Philadelphia’s earliest enclave, Frankford, consisted of Lenni Lenape Indians and Swedish settlers prior to the founding of the Pennsylvania colony by William Penn in the early 1680s. Immediately following Pennsylvania’s establishment in 1681, Quaker settlers constructed a meetinghouse, built in 1684, and post office at William Penn’s request in what was initially designated the Manor of Frank during the mid-1680s. Situated to the northeast of the city of Philadelphia, Frankford’s importance as a center of commerce and trade grew principally because of its geographic location along the King’s Highway (present-day Frankford Avenue). It developed into a manufacturing village in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, drawing in German and English settlers, who opened numerous mills along the Frankford Creek. In addition to European settlers, free blacks established fraternal, religious, and anti-slavery institutions in the village to counter the creeping signs of residential segregation and employment discrimination surrounding them. Located within the boundaries of Philadelphia County, Frankford’s commercial dominance attracted nearby farmers, who principally resided in Northeast townships, such as Lower Dublin and Moreland, to process their raw materials and farm products in Frankford’s bustling mills. The village also became a vital munitions site for the U.S. Army after the War of 1812, when the federal government began the construction of an arsenal, completed in the mid-1820s, along the banks of the Frankford Creek.

Other settlements, primarily centered on farming and mill activity, dotted Northeast Philadelphia’s rural terrain and creek beds prior to and following the Consolidation Act of 1854, with pockets of gilded affluence appearing sporadically along the Delaware River in the late nineteenth century. Multiple townships throughout the Northeast possessed small, farming enclaves and communities, especially Bustleton, Somerton, and Fox Chase. In the early 1850s, residents from the Northeast decried the city’s plan to annex their communities into a newly consolidated city-county governance authority, which aimed to confer municipal services and policing functions on outlying suburbs in exchange for jurisdictional control over their neighborhoods. Some Bustleton residents, afraid of losing their independence, resisted the city’s annexation plan in 1852 by initiating legislation, which ultimately failed, to thwart the proposal. While the Northeast remained predominantly rural following the Act of Incorporation’s passage, some of Philadelphia’s well-heeled elite erected palatial mansions and estates in Holmesburg and Torresdale, with the most notable Victorian structure being the opulent Glen Foerd mansion, which still overlooks the Delaware River, in Torresdale.

Flourishing Industry

Additional industrial enterprises and communities emerged and flourished immediately north of Frankford along the Delaware River in the mid- to late nineteenth century, as some industrialists sought additional space to accommodate their expanding companies. Henry Disston (1819-1878), an English industrial entrepreneur, moved his burgeoning saw works enterprise from the congested confines of Northern Liberties to Tacony in 1872. Upon relocating his saw works, he gradually constructed a self-sufficient company town to house his workers. Disston’s company town attracted both existing and newly arrived ethnic, European immigrant communities, namely Irish, Italian, Polish, and Germans, and offered them generous benefits and homeownership opportunities, melding them into a productive and loyal working-class community.

In the early twentieth century, Philadelphia’s elected officials embraced the City Beautiful Movement with the intention of improving the city’s infrastructure and attracting affluent suburbanites to downtown Philadelphia. One of these projects, the Northeast Boulevard, which was renamed the Roosevelt Boulevard in 1918, opened in 1914 to much fanfare, as builders and private developers soon capitalized on the city’s investment in the roadway to construct single- and twin-family dwellings along its expansive corridor, especially in the Northwood section of Frankford in the lower Northeast. As the Roaring Twenties progressed, commercial development also coincided with residential expansion in the lower Northeast. Local booster organizations, especially the establishment of the Northeast Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce, and Sears-Roebuck’s new merchandising facility, which opened in 1919, symbolized the Northeast’s flourishing commercial identity.

The Great Depression’s onset, however, soon dampened the homebuilding spirits of Northeast boosters and exacerbated economic tensions between middle-class WASPs, who inhabited bungalows and mansions along the Boulevard, and ethnic whites and working-class blacks, who remained consigned to industrial enclaves closer to the Delaware River. In the mid-1930s, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, which created detailed, color-coded residential security maps to demarcate desirable from dilapidated housing throughout the city of Philadelphia, documented and widened, through its discriminatory redlining policies, the emerging residential and class disparities in the lower Northeast.

The oldest, residential precincts, especially in Tacony and Wissinoming, primarily housed skilled workers laboring in the Disston Saw Works and other industrial facilities east of Torresdale Avenue. Meanwhile, Mayfair, Lawndale, and the Northwood section of Frankford, home to a mixture of white- and blue-collar workers, had experienced significant construction and residential upgrades immediately south of Cottman Avenue and along Roosevelt Boulevard during the 1920s and early 1930s.

Public Housing Segregation

The growing demand for adequate housing during World War II, in fact, led to increased racial segregation in, and civic resistance to, public housing projects in Northeast Philadelphia. The 1941 Lanham Defense Housing Act established the funding provisions that facilitated the construction of Pennypack Woods and Oxford Village I in 1942, with both housing complexes only accepting applications from white war workers and their families. Speaking on the behalf of anxious, middle-class homeowners in the Northeast, the Northeast Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce resented what it regarded as the federal government’s intrusive wartime housing schemes, openly assailing the government’s intention to provide affordable housing to war workers in the Northeast, albeit on racially segregated terms.

Generous government benefits, namely the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (GI Bill) and FHA home lending policies, assisted returning veterans, the majority of whom were white, in their quest to move from Philadelphia’s densely packed industrial neighborhoods to the quasi-suburban atmosphere of Northeast Philadelphia following World War II. Prominent builders, most notably Hyman Korman (1891-1964) and A.P. Orleans (1888-1981), capitalized on these circumstances to expand home construction west of Roosevelt Boulevard in the Near Northeast, especially in Rhawnhurst, Lawndale, and Oxford Circle, in the late 1940s and 1950s. The Far Northeast, on the other hand, remained largely undeveloped until the late 1950s and 1960s, at which point large contingents of affluent, white households, many of whom were Jewish, were drawn to Cape Cod and ranch dwellings designed with a suburban feel nestled in Bustleton and Somerton. Residential development of a mixed, aesthetic character, containing both row house and single-family dwellings, also unfolded east of Roosevelt Boulevard in the Far Northeast, especially in Torresdale, Holme Circle, and Academy Gardens, throughout the 1950s and 1960s, where an assemblage of white, ethnic Catholics with strong community affiliations to nearby parishes bought homes.

Commercial development, especially shopping centers, also molded the spatial alignment of Northeast Philadelphia’s neighborhoods in the postwar period. Just as mini-strip shopping centers began to dot the Northeast’s still developing landscape during the 1950s and early 1960s, some Northeast residents, apoplectic about commercial overexpansion in their neighborhoods, requested the construction of a major shopping facility to counteract the sometimes unwieldy dimensions of commercial growth in the Northeast. In 1961, for instance, civic boosters, city officials, and residents congregated at the Bustleton-Cottman shopping center—a newly erected major regional shopping facility that openly competed for Northeast customers with Philadelphia’s central business district—to mark its opening, with Gimbels serving as its principal anchor department store.

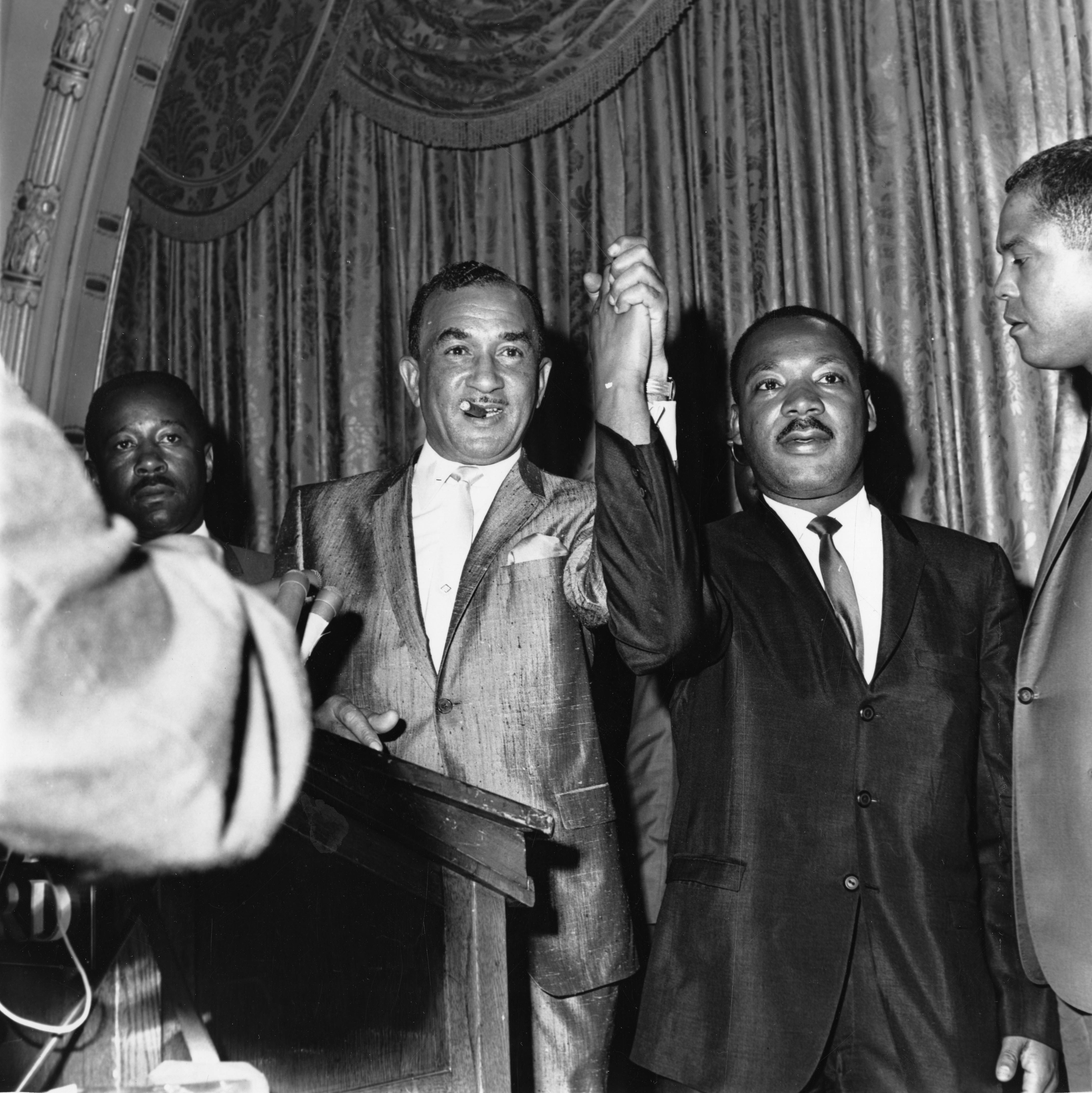

Amid the rising tide of middle-class prosperity coursing through Northeast Philadelphia in the postwar period, there also developed a residential backlash among white homeowners toward proposed zoning changes to accommodate public housing in residential neighborhoods and fair housing proposals offered by civil rights advocates. In July 1959, Harold Stassen (1907-2001), the Republican mayoral candidate, sought the support of Northeast voters by claiming that he would disassemble “City Hall’s bungling socialistic experiments” aimed at providing public housing for low-income families and racial minorities in Northeast neighborhoods. While popular defiance toward public housing in the Northeast persisted over the next two decades, Northeast Realtors and residents also resisted anti-discriminatory overtures in the private housing market, as calls for fair-housing legislation mounted among Philadelphia city officials and state legislators in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Although the Pennsylvania state legislature passed a fair-housing law in 1961 to end discriminatory practices in the private marketplace, Cecil B. Moore (1915-79), a prominent African American civil rights advocate who grew dissatisfied with the pace and trajectory of residential desegregation, still accused the Northeast of being a “lily-white island” within the city’s limits in 1964.

Racial animosities between whites and blacks in Northeast Philadelphia intensified further around busing and school-desegregation proposals during the late 1960s and 1970s. As president of the School Board of Philadelphia, Richardson Dilworth (1888-1974) faced staunch opposition from white residents in both the Near and Far Northeast after the school board, working in conjunction with the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations, released its 1968 desegregation plan for the city’s public schools. In their effort to achieve racial equilibrium and enhance educational standards across Philadelphia’s public school system, Dilworth and the school board encountered massive resistance to the busing of Black students into the Northeast’s overwhelmingly white schools, and “reverse” busing, which entailed busing white children into predominantly Black city schools.

Rizzo’s Mandate

Repeated attempts to implement full-blown school desegregation waned during the mayoral tenure of Frank Rizzo, as he appeased many white residents’ anxieties, especially after receiving an electoral mandate from Northeast whites in 1971, by curtailing liberal demands for racial parity within Philadelphia’s public schools. Public support for mandatory school desegregation in the city’s public schools eventually faded in the mid-1970s, at which point city officials and residents agreed to institute a voluntary school-desegregation plan commencing in 1978, which experienced less popular resistance in the Northeast.

As deindustrialization and white flight threatened Philadelphia’s already shaky fiscal foundations and deteriorating municipal services during the 1970s and early 1980s, some Northeast residents, including Republican State Senator Hank Salvatore (b. 1922), questioned the logic of remaining wedded to the “City of Brotherly Love.” After W. Wilson Goode (b. 1938), the first African American elected mayor of Philadelphia, made repeated calls in the 1983 mayoral election to erect a “mini-City Hall” in Northeast Philadelphia in order to offset Northeast residents’ fears about declining city services, Senator Salvatore, unmoved by Goode’s proposal, declared his intention to introduce legislation in the state legislature that would permit Northeast Philadelphia to secede from the city and become formally known as “Liberty County.” Goode, living up to his promise, opened the mini-City Hall in the Northeast Center Shopping Center along Roosevelt Boulevard in 1985, severely undercutting the legitimacy of Salvatore’s secession agenda, which lost its popular appeal by the late 1980s.

Over the subsequent two decades, Northeast Philadelphia underwent significant demographic and racial changes to become an increasingly diverse, urban community. Starting in the 1990s, white families and individuals relocated, principally because of their economic mobility and aging households, to the surrounding suburban counties and outside the Philadelphia metropolitan region in increasing numbers. In 2011, the Pew Charitable Trusts released a citywide population study that documented the dramatic racial and ethnic transformations that had occurred throughout Philadelphia during the previous twenty years. It found that Northeast Philadelphia’s white population had fallen precipitously, from 92 percent in 1990 to 58.3 percent in 2010. As middle-class whites migrated outside the city’s limits, racial minorities began the process of inhabiting the once predominantly white corridors of Northeast Philadelphia and relied on affordable mass transportation links, such as the Frankford El, for their daily work commutes into the city. Indian families and ethnic Russians moved into the Far Northeast neighborhoods of Bustleton and Somerton, respectively, while African Americans, various Asian groups, and Hispanics relocated from North Philadelphia into the lower Northeast neighborhoods of Mayfair, Frankford, and Oxford Circle. Once a bastion of racial defiance and material affluence, Northeast Philadelphia evolved into a dynamic, cosmopolitan atmosphere in the early twenty-first century to embrace economic, cultural and racial diversity in its private and public spaces.

Matthew Smalarz, who grew up in Northeast Philadelphia, is a Ph. D. candidate at the University of Rochester who teaches at Manor College. His dissertation examines middle-class whiteness in the making of private and public space in Northeast Philadelphia following World War II. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Look Up! Henry Disston's Company Town (PlanPhilly.com)

- Greater Northeastern Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce

- An Urban Village Built on Cooperation (Pennypack Woods) (Philly.com)

- Philadelphia Redlining Maps (University of Pennsylvania)

- Tookany/Tacony-Frankford Watershed History (Philadelphia Water Department)

- Historical Society of Frankford

- Northeast: Mayfair Then and Now (Philadelphia Neighborhoods)