Corrupt and Contented

Essay

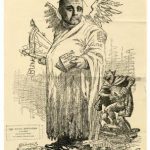

In July 1903, at the height of the period of reform we have come to call the Progressive Era, crusading journalist Lincoln Steffens published the fifth in a series of articles exposing municipal corruption in the United States. His subject was Philadelphia, and to his mind it was worse than any other place he had investigated. “All our municipal governments are more or less bad,” Steffens declared. “Philadelphia is simply the most corrupt and the most contented.”

Steffens’ reports helped launch a period of investigative reporting that President Theodore Roosevelt labeled “muckraking” in a moment of pique, but the phenomenon was otherwise quite compatible with his own reform orientation. Muckraking faded with the reform era itself, but the impression never fully disappeared that Philadelphia deserved the label Steffens had given it. Inquirer columnist Karen Heller invoked Steffens more recently in connection with reports of political pressure to direct $50 million to a favored candidate to operate a charter school. Can so little have changed? Is Philadelphia still corrupt and still contented?

Steffens was in the business of selling magazines, and no doubt he heightened his account for effect. There’s no evidence, really, for the story he recounted of a “party of boodlers” divvying up their graft in unison with the ancient chime of Independence Hall. His account of misfeasance was well enough documented to leave a lasting effect, however. Despite a number of good government efforts, some of which continue today, including the Committee of Seventy dating to 1904, the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia, which started as the Bureau of Municipal Research, and the Fels Institute at the University of Pennsylvania, the suspicion lingers that the public remains all too acquiescent in a political system riddled with conflicts of interest and hidden from adequate public scrutiny.

Anti-Immigration Sentiment

The system Steffens described had its roots in the nineteenth century. Some blamed election day improprieties and the exchange of political favors on the bad effect of masses of newcomers to the city, many of them immigrants with little experience with democratic practice. Anti-immigration sentiment reached a peak with the mid-century rise of a nativist movement, which attempted to extend the waiting period for citizenship to 21 years for the foreign born and to discipline immigrant workers through the prohibition of alcohol. The year this movement reached its peak, in 1854 with the election of a nativist mayor, the city consolidated with the county, and a very different political dynamic ensued.

An expanded city needed a variety of public services. The provision of new streets, gas and water mains, and public transportation all generated opportunities for money to change hands. As permits were issued, as charters were granted, as the number of city workers expanded to 15,000 by the time Steffens wrote, the lines between public power and private profit converged. Something had to hold this fragmented system together, and taking a cut—“honest graft’ as Tammany Hall’s George Washington Plunkitt famously labeled the practice—seemed to be part of the necessary price. But that price could be exorbitant too. The traction magnates William L. Elkins and Peter A.B. Widener consolidated so much money and power for themselves, they formed the model for Theodore Dreiser’s own muckraking trilogy, beginning with The Financier in1912.

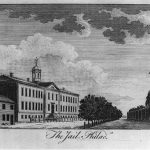

One monument to the system not matched in any other city Steffens examined was Philadelphia City Hall. Covering fully four acres at the heart of the city where William Penn had laid out four squares to form a central park, the massive structure took thirty years to build and cost $24 million, fully $14 million in overruns. Politicians shepherding the project extracted a host of benefits for themselves, all the time keeping thousands of city workers employed.

The political machine Steffens described had only recently consolidated, following a reform effort that culminated in passage of a new city charter in 1887. What he described was the aftermath of such efforts, when the “morning glory” reformers, as their critics liked to call them, retired from public life to take up their private pursuits once again. Given even greater power under the new rules, partisan politicians again emerged triumphant, supported by continued growth in patronage positions that reached 23,000 in the 1920s, second only to New York City.

1951: Republican Reign Ends

Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal failed to unseat the city’s Republican political machine, but spurred by many of the reforms instituted at the national level in the 1930s, Joseph Clark, together with Richardson Dilworth, brought the Republican reign to an end with their elections as mayor and district attorney respectively in 1951. Not incidentally, their election coincided with passage of a home rule charter, which instituted a professional managing director for the city and required civil service exams for many jobs that had been previously doled out as political patronage.

It might be too much to accept Karen Heller’s implication that the Clark-Dilworth years represented only a short hiatus between 85 years of entrenched and calcified Republican rule and 60 years of entrenched and calcified Democratic rule. Whatever good intentions or formal mechanisms were instituted in the 1950s, however, they clearly did not prevent the practice we routinely describe as pay-to-play from infecting public governance, not just in Philadelphia but throughout the region. The central features of the ward system Steffens described in 1903 remain in place today in the city, and in the suburbs service contracts can be repaid quite legally in the form of political contributions to the party controlling the bidding. Occasionally a politician will step far enough over the line to be punished under the law. Vincent Fumo and Wayne Bryant come most readily to mind. For the most part, the system prevails in forms that would be still recognizable to earlier generations.

It was Steffens’ belief that his reports would arouse public opinion sufficiently that it would ultimately cleanse the system. That tradition continues with investigative journalism and widespread use of the Internet to expose corruption. It’s just possible that the Tea Party and Occupy Philadelphia each manifest signs of an awakened electorate. Like Steffens, however, we should not be blind to the obstacles to reform. Transparency and accountability need mechanisms for their sustainability. It won’t be enough to reign in political excesses like DROP (Deferred Retirement Option Program) or to assure that only verified voters cast their ballots. If this is to be yet another Progressive era, voters need to pressure both political parties to make far more effective use of public revenues, even while acknowledging how important those investments are to the modern metropolis.

Howard Gillette is Professor of History Emeritus at Rutgers University-Camden. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Published in partnership with the Historical Society of Philadelphia, with support from the Pennsylvania Humanities Council.