African American Migration

By James Wolfinger | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

People of African descent have migrated to Philadelphia since the seventeenth century. First arriving in bondage, either directly from Africa or by way of the Caribbean, they soon developed a small but robust community that grew throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Although African Americans faced employment discrimination, disfranchisement, and periodic race riots in the 1800s, the community attracted tens of thousands of people during World War I’s Great Migration. Drawn by the promise of jobs during the two world wars, Philadelphia’s African Americans created one of the largest Black communities in the urban North in the twentieth century. Deindustrialization and suburbanization from the post-World War II period to the early 2000s contributed to rising rates of poverty, racial tensions, and disinvestment in Black neighborhoods, but the Black community continued to attract new migrants.

Arriving as early as 1639 with the Delaware Valley’s earliest European settlers, the region’s first African residents were few in number and worked as slaves for Swedish, Dutch, and Finnish settlers. Their population grew in 1684 when the ship Isabella brought 150 African slaves to Philadelphia. But with European immigrants available to do the bulk of the region’s manual labor, the slave trade brought only a few Africans each year until the 1750s, when the Seven Years’ War limited German and Scotch-Irish immigration. At that point, the slave trade spiked and anywhere from 100 to 500 Africans came to Philadelphia each year in the 1750s and 1760s. Most new arrivals came on ships from Africa but some fugitive slaves entered the city from Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. By the Revolutionary era, slaves accounted for some one-twelfth of Philadelphia’s population of roughly 16,000 people.

As Philadelphia’s Black population grew, it both encountered social problems and developed community institutions that endured for generations. The law often limited Black immigrants’ advancement, with, for example, Black Codes in the 1720s defining Africans as “an idle, slothful people” and emancipation legislation in the 1780s providing only for gradual manumission, which meant the state still held a few slaves as late as the 1840s. Schools, except for those run by concerned citizens such as the Quaker abolitionist Anthony Benezet (1713-84), seldom accepted Black children. And adults–slave or free–generally found themselves relegated to menial labor, which meant lifelong poverty.

The Free African Society

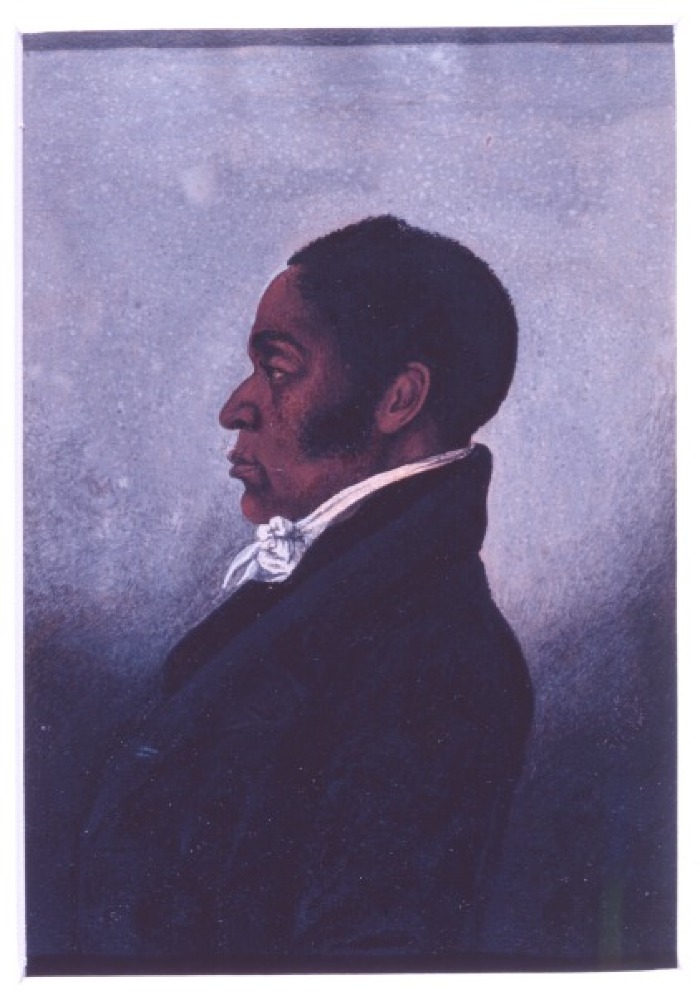

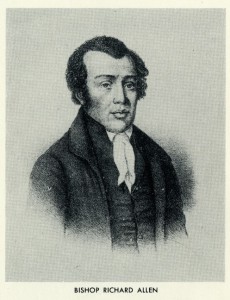

Black Philadelphians countered these problems in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries by building institutions such as the Free African Society (America’s first independent Black organization), founded by Richard Allen (1760-1831) and Absalom Jones (1746-1818), and Allen’s Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (later known as Mother Bethel), and by supporting Freedom’s Journal (the nation’s first Black newspaper). Such activity made Philadelphia a center of abolitionism, especially after James Forten (1766-1842), one of the richest Black men in America, gained fame for funding the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison’s (1805-79) Boston-based newspaper, The Liberator.

In the half century leading up to the Civil War, Philadelphia attracted the largest Black population outside the slave states even though the city’s acceptance of African Americans was mixed at best. The number of Black Philadelphians stood at 15,000 in 1830, grew to nearly 20,000 by 1850, and topped 22,000 in 1860. The population clustered in South Philadelphia near what is today Center City, but smaller concentrations also developed in Kensington, Northern Liberties, and Spring Garden. African Americans came because of the Black community’s reputation as a vibrant political, cultural, and economic center, and Philadelphia, true to its antislavery reputation, became a major stop on the Underground Railroad, especially for slaves making their escapes through Maryland and Delaware. But jobs–the great lure for most immigrants–were mostly physically demanding and low-paying, with only a few people managing to secure positions as barbers, caterers, doctors, ministers, and teachers. Competition for work, coupled with antiabolitionist sentiment, fired conflicts between African Americans and working-class whites, especially Irish immigrants. Between 1828 and 1849 Philadelphia experienced five major race riots that destroyed Black homes, businesses, and abolitionist halls, leading one observer to call the city “illiberal, unjust and oppressive.” Such sentiment was not limited to the city: In 1838, Pennsylvania ratified a new constitution that officially disfranchised African Americans.

Despite the problems confronting Black Philadelphia, the community continued to attract migrants in the second half of the nineteenth century. The population grew to nearly 32,000 in 1880 and almost doubled to some 63,000 in 1900. Black Philadelphia was large enough to muster eleven regiments to serve in the Civil War, and in the ensuing decades it supported approximately 300 Black-owned businesses, including the Philadelphia Tribune (established in 1884) and Douglas Hospital (opened in 1895). By the 1890s, the community had the size and vitality to command sociological investigation, which took the form of W.E.B. Du Bois’s (1868-1963) classic study The Philadelphia Negro (1899).

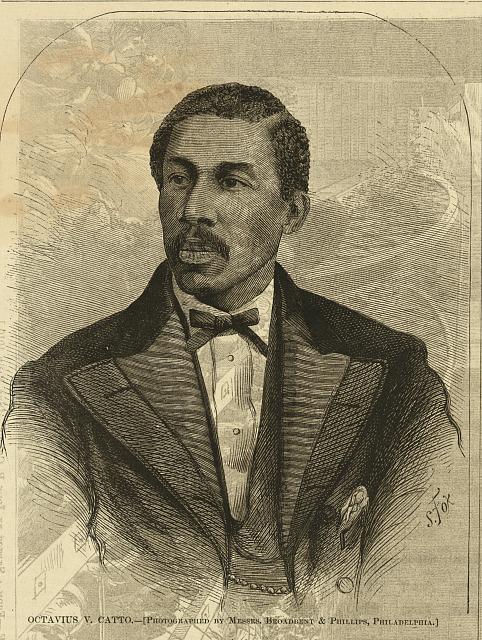

The Civil War experience plus Black Philadelphia’s size led to greater activism on the “race question.” African Americans, led by Octavius V. Catto (1839-71), pushed to regain the right to vote, end segregation of the city’s schools, and desegregate the streetcars. Feeling the pressure, the Pennsylvania state legislature passed a law requiring street railways to carry passengers regardless of color in 1867 and ended legal segregation of the education system in 1881 (although the city’s schools remained segregated by custom for decades afterwards). The Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution compelled Pennsylvania to grant African Americans the franchise in 1870, but, signaling Philadelphia’s continuing racial difficulties, Catto was shot and killed attempting to vote in 1871.

Black Migration North

The greatest wave of Black migrants in Philadelphia’s history to that point came during World War I when the conflict overseas choked off European migration and Northern businesses across the United States looked to the South for labor. This massive population movement, known as the Great Migration, changed the face of American cities from Boston and New York City to Detroit, Chicago, and beyond. Philadelphia’s Black population more than doubled, rising from 63,000 in 1900 to 134,000 in 1920, with most of the migrants coming from the Eastern seaboard. Other industrial cities in the area, such as Camden, Chester, and Norristown, also saw their Black communities grow, but the great bulk of the immigrants moved to Philadelphia. Women played a critical role in the migration, helping establish communal and kin networks that brought migrants to Philadelphia.

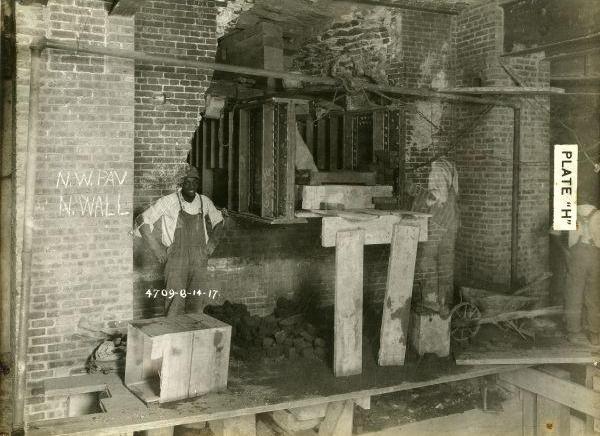

Most newly arrived African Americans were best described as the “working poor” and they sought employment at the area’s major companies such as the Pennsylvania and Reading Railroads, Baldwin Locomotive, Midvale Steel, Cramps Shipyard, and the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company. White Philadelphians, many from families only recently arrived in the United States as immigrants, regarded African Americans as competitors for jobs and decent housing. Their consternation about Blacks in their workplaces and neighborhoods led to a number of racial conflicts that mirrored events across the nation. Philadelphia and Chester, Pennsylvania, both had riots in 1918 that killed five people in each city, and Coatesville (45 miles west of Philadelphia) a few years earlier in 1911 witnessed the lynching of a steelworker named Zachariah Walker. Surveys showed that Philadelphia was so inhospitable that many new residents contemplated returning to the South. Some formed the Colored Protective Association or supported the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to assert their rights.

Philadelphia’s in-migration continued in the ensuing decades, tapering off only during the Great Depression. By the end of the 1920s, Philadelphia’s Black population grew to 220,000 people and the community established a much larger presence in North and West Philadelphia. Enough African Americans enjoyed the era’s prosperity that some critics accused better-off Black Philadelphians of shirking their responsibilities to the poor and working class. Such criticisms diminished in the 1930s when the Depression devastated the city, especially its Black community where unemployment exceeded 50 percent. Across Philadelphia, at textile mills, metal shops, and other places of employment, African Americans faced the age-old problem of “last hired, first fired.” For many working-class Blacks, like the city’s white ethnic groups, economic hard times led them to support Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, a sea change in a city dominated by the Republican Party for a century. Only with the coming of World War II and its attendant federal military supply contracts did the situation improve. African Americans, although some of the last people to gain employment, got jobs at Sun Shipyard, the Philadelphia Transportation Company, and elsewhere. Still, they faced discrimination as Sun Ship created a segregated yard and the transit company endured one of the costliest hate strikes of World War II.

Migration Despite Discrimination

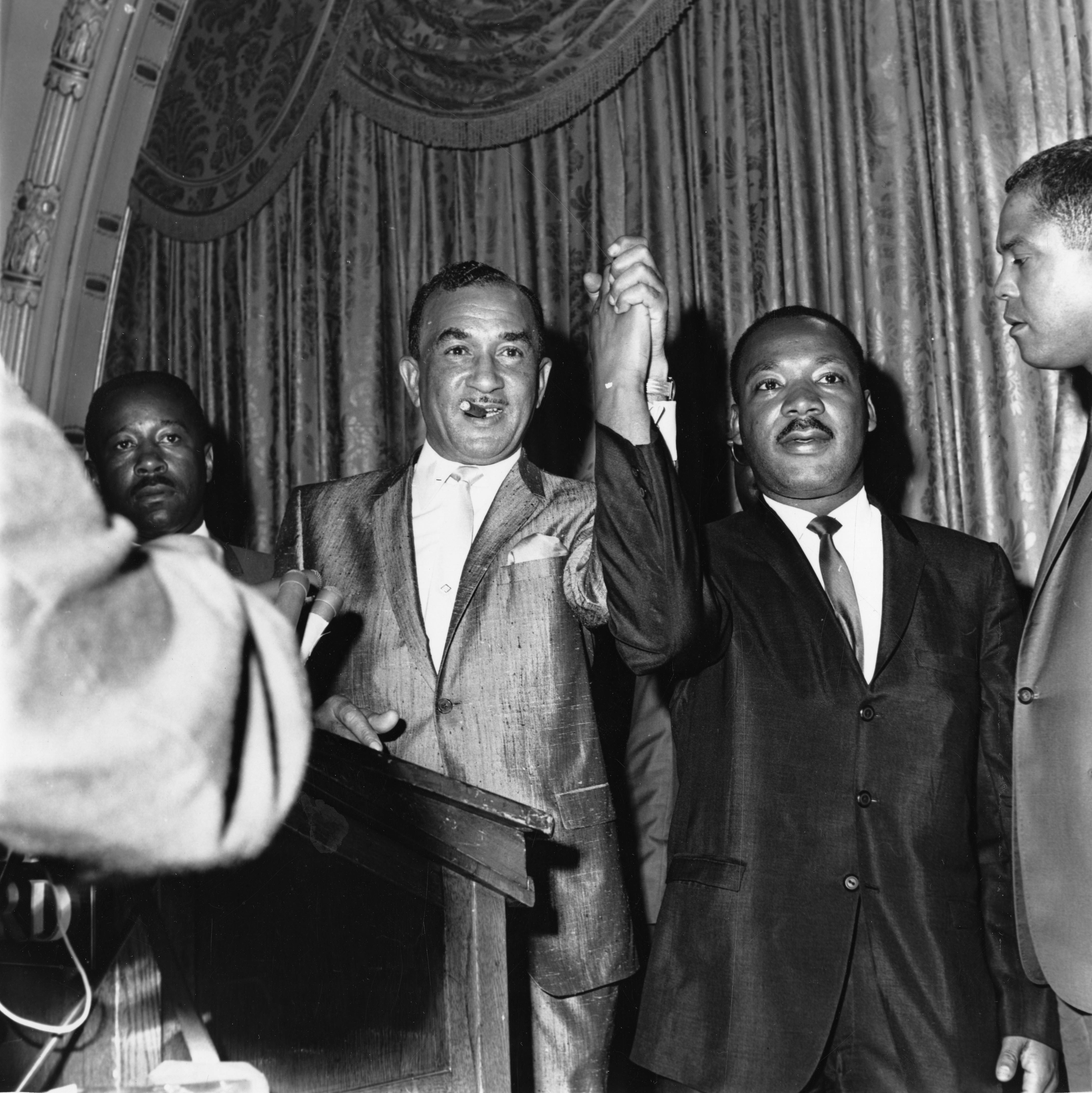

Despite the continued workplace discrimination, Philadelphia attracted tens of thousands of migrants during the war and the numbers continued to rise for decades afterwards. The city’s Black population stood at 250,000 in 1940, grew to 375,000 in 1950, and peaked at some 655,000 residents in 1970. By that year, African Americans represented one-third of the population. Unfortunately for Black Philadelphians, their numbers grew just as the city’s economy declined. For generations a national industrial leader, especially in smaller craft occupations, Philadelphia lost textile, metal manufacturing, and electronic production jobs by the tens of thousands from the 1950s-1970s. Some of the jobs moved to the South and foreign countries while others migrated to the suburbs. African Americans found that because of discriminatory housing practices they could not follow the jobs to suburban Bucks and Montgomery counties, and they increasingly became locked in poor inner-city neighborhoods shorn of jobs and resources. These circumstances led to a more radicalized civil rights movement championed by Cecil B. Moore (1915-79) as well as activism by women who demanded the support of public institutions for their families.

In the last three decades of the twentieth century, Philadelphia’s Black population stabilized at between 630,000 and 655,000 people. As white Philadelphians moved to the suburbs, African Americans became a larger portion of the overall population, 43 percent in 2000. The changing population mix created tense political contests, with law-and-order candidate Frank Rizzo (1920-91) serving two mayoral terms from 1972 to 1980. Wilson Goode (b. 1938) finally secured a representative share of political power for the Black community when he served as mayor from 1984 to 1992, although his first term was marred by an infamous conflict with the Black liberation group MOVE.

Goode’s emergence along with that of Judge Leon Higginbotham, Reverend Leon Sullivan, and others showed the vitality of Philadelphia’s African American community that continued into the first decade of the twenty-first century. The 2010 census demonstrated that Philadelphia remained attractive to Black migrants: the total population stood at 1,526,000, with African Americans comprising 43.4 percent of that total (662,000 residents) and whites comprising 41 percent (626,000 residents). Philadelphia attracted more Hispanic and Asian immigrants in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century (12 percent and 6 percent of the population, respectively in 2010), but it remained a magnet mostly for African American migrants who continued to find opportunities as well as stony ground in the city. John Street (b. 1943) and Michael Nutter (b. 1957) were elected mayor and Congressman Chaka Fattah emerged as a senior member on the House Appropriations Committee. Unemployment, high public school dropout rates, and other problems persisted, but the vibrancy of Philadelphia’s Black community continued, a vibrancy built by migrants over nearly four centuries.

James Wolfinger is associate professor of history and education at DePaul University in Chicago, Illinois. He is the author of numerous articles on Philadelphia’s history as well as the book Philadelphia Divided: Race and Politics in the City of Brotherly Love. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Goin' North: Stories From the First Great Migration to Philadelphia

- In Motion: The African-American Migration Experience

- The African American Museum in Philadelphia

- Civil Rights in a Northern City: Philadelphia (Temple University)

- Mother Bethel AME Museum

- African American Migration Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)