Book Publishing and Publishers

Essay

Between 1750 and 1800, Philadelphia became the center for book printing and publishing in the United States, surpassing New York and Boston. Although Philadelphia lost that primacy in the nineteenth century, firms specializing in medical and religious publishing continued to do well. By the mid to late twentieth century, however, as the publishing industry consolidated, few independent Philadelphia book publishers remained.

In the late seventeenth century, William Bradford (1663-1752) established the first printing press in Philadelphia. For many years, he was the only printer in the city. In colonial America, printers often acted as booksellers and sometimes as publishers of broadsides, pamphlets, newspapers, and almanacs. Book publishing was far less common during this period because it was so risky. Printing and binding books was expensive, and would-be publishers had no guarantee that they would be able to recoup their investment through sales. Instead, printers preferred to import books from Great Britain.

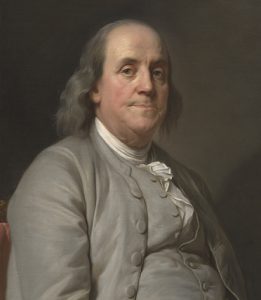

Nonetheless, a few enterprising printers in the Philadelphia region published books during the eighteenth century. Perhaps the most famous of these was Benjamin Franklin (1706-90). Over the course of his career, Franklin printed and financed sixteen books including Samuel Richardson’s novel Pamela (1742-44) and Philadelphia politician and scholar James Logan’s translation of Marcus Tullius Cicero’s Cato Major (1744). One of Franklin’s contemporaries was Christopher Saur (1695-1758). Saur set up shop northwest of Philadelphia in Germantown, where he focused on printing and publishing German-language materials to serve a growing population of German immigrants.

Another early printer and publisher who operated outside of Philadelphia was Delaware-born Isaac Collins (1746-1817). Collins got his start in Philadelphia as an apprentice before moving to Burlington and, later, Trenton, New Jersey. Collins mostly published religious texts as well as a few schoolbooks. Scottish-born printer Thomas Dobson (1751-1823) took on perhaps the most ambitious printing and publishing project during this period: the first American edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1789-98). In order to finance this expensive multivolume work, Dobson gathered subscribers from across the country, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Still, Dobson had trouble finding enough support for the project, and the Britannica was not a financial success.

A Surge in Printers

In the second half of the eighteenth century the number of printers began to grow substantially. Printers gravitated to Philadelphia because of its large, cosmopolitan population, as well as its high concentration of learned organizations, from the American Philosophical Society to the University of Pennsylvania. Geographic location played an important role as well. Philadelphia’s proximity to important rivers and roads meant that printed materials could more easily reach markets in the South and West. By the late 1830s, however, Philadelphia’s growth slowed. With the opening of the Erie Canal, New York possessed superior waterways as well as several large general publishing firms that proved to be tough competition.

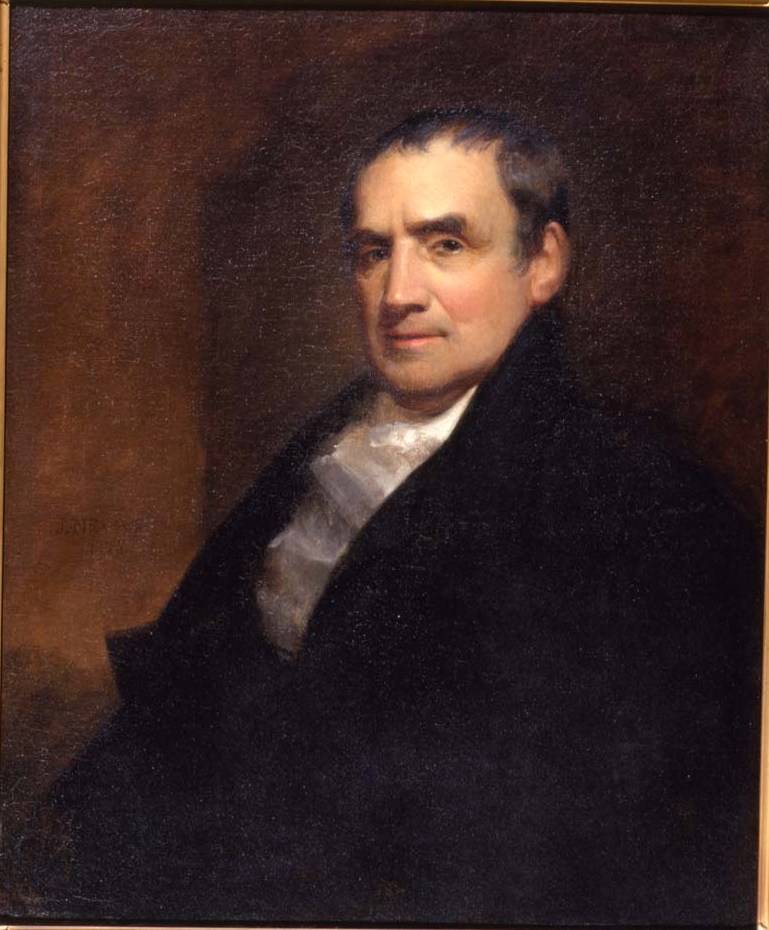

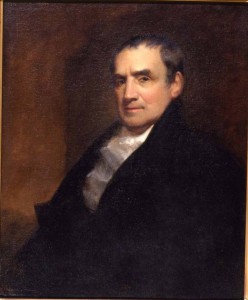

By the nineteenth century, the market for print had expanded considerably. More Americans could read than ever before, and there was a growing sense that an educated society was crucial to a thriving democracy. These changes, along with a booming economy, made printers more willing to take risks and publish books. It was also during this period that the line between printer and publisher became more defined. Mathew Carey (1759-1839) is generally considered Philadelphia’s first modern publisher. Born in Ireland, Carey got his start as a printer but soon focused his attention solely on publishing and bookselling. He found success publishing British novels, such as Susanna Rowson’s Charlotte Temple (first published by Carey in 1794). Carey also pioneered new methods in marketing and distribution that few American publishers had tried before. In the 1820s, Carey asked his oldest son, Henry Charles Carey (1793-1879), and his son-in-law, Isaac Lea (1792-1886), to take over the firm, under the new name Carey & Lea. The firm went on to publish a wide variety of books, including popular novels by Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper. Eventually, fierce competition from the growing Harper Brothers in New York helped convince the firm to shift its focus to medical publishing. Carey & Lea was located in the right city for such a specialization, as Philadelphia was home to a growing medical community which included two medical schools. Over the years, the firm changed names several times. By the twentieth century it was known as Lea & Febiger.

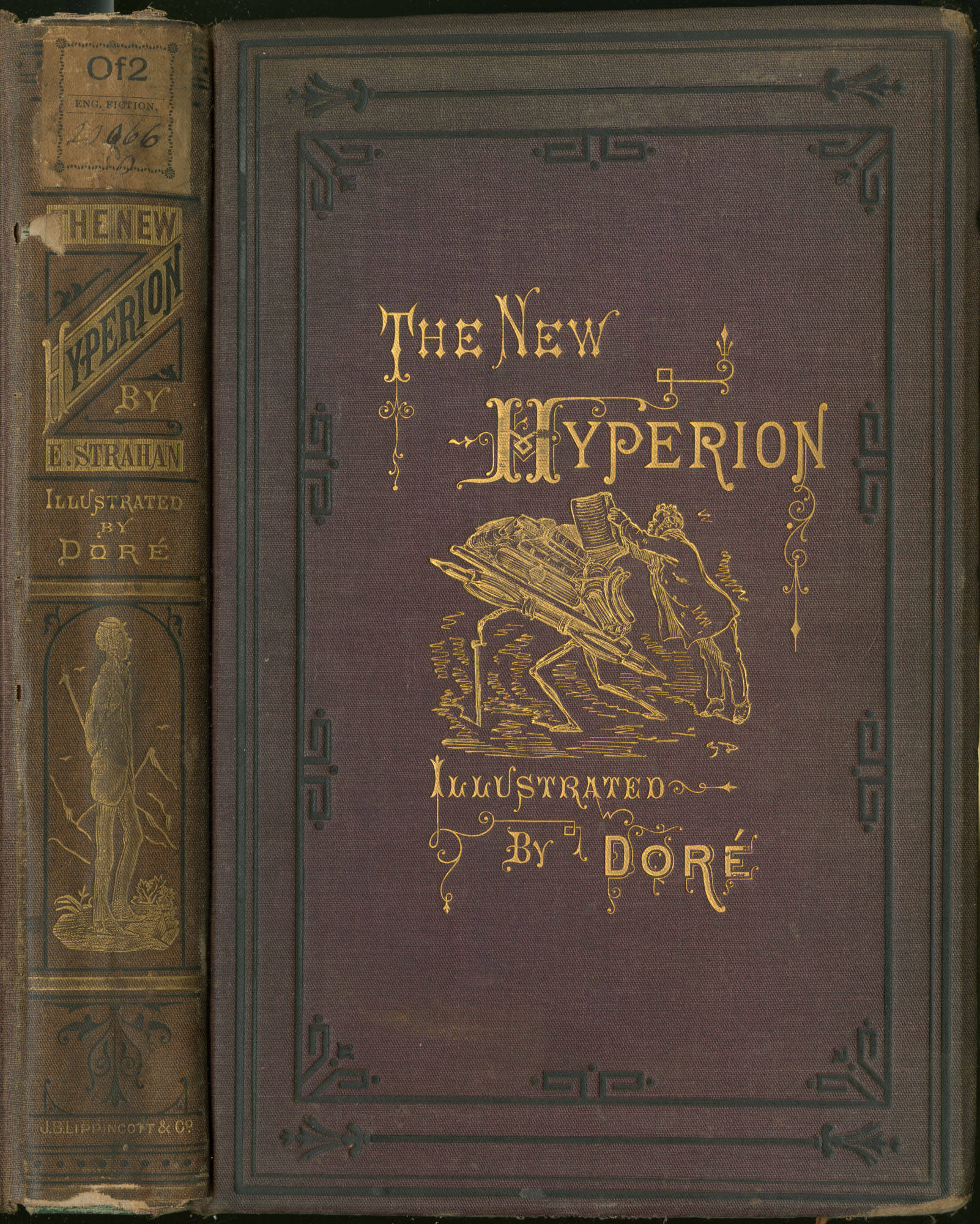

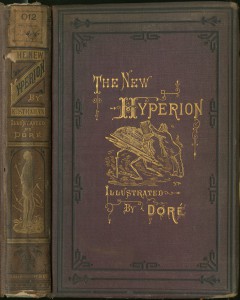

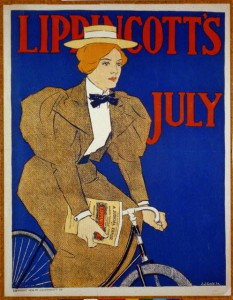

Another important nineteenth-century Philadelphia publishing firm was J.B. Lippincott & Co. Founded in 1836 by New Jersey-born Joshua B. Lippincott (1813-86), the firm got its start publishing religious books. By the 1850s Lippincott began to focus on medical publications and gift books. While Lippincott was known as a publisher, the firm did considerable work as a jobber, helping to distribute books published by other firms to retail stores in the South. Lippincott also operated a large factory for printing and bookbinding at 715 Market Street. The company was incredibly successful, by the end of the nineteenth century printing around 2,000 books per year.

Religious publishers thrived in Philadelphia during the nineteenth century. These organizations, financed largely by donations, sold some of their publications but mostly gave books away for free. The Philadelphia Bible Society, founded in 1809, published Bibles and New Testaments. The American Sunday School Union got its start in Philadelphia in 1824 and soon became one of the largest national religious publishing societies in the United States. The group aimed to establish Sunday Schools across the country and to supply each school with religious books appropriate for children. In addition to noncommercial publishers, by the mid-nineteenth century many general publishers partnered with specific denominations to supply religious works. J.B. Lippincott & Co., for example, allied with the Protestant Episcopal Church.

Subscription Publishing

Another distinctive aspect of the book trade in Philadelphia was its focus on subscription publishing. Subscription books were sold door to door by agents, instead of through a bookstore. Many types of books were sold by subscription, including novels, histories, and reference works. While Hartford and Chicago are often identified as centers of the subscription book trade, Philadelphia also played an important role. In fact, Mathew Carey was one of the earliest American publishers to rely on a book peddler to sell his books. His book agent, a clergyman and author named Mason Locke Weems (1759-1825), traveled across the South trying to convince people to buy. After the Civil War, a number of publishing firms specializing in subscription books formed in Philadelphia, including T. Ellwood Zell, Gebbie and Barrie, and later, the National Publishing Company. Even general publishers like J.B. Lippincott & Co. maintained a subscription book department. Most subscription publishers eventually went bankrupt during the early twentieth century, when the practice of selling books door to door largely ended.

Despite the many book publishers in Philadelphia during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, few were women. Two of city’s earliest female publishers were Jane Aitken (1764-1832) and Lydia Bailey (1779-1869). Although they were printers first and foremost (Lydia Bailey did printing work for Mathew Carey, among others), Aitken and Bailey occasionally acted as publishers. Aitken, for example, published the first American translation of the Bible in 1808. By the late nineteenth century, although more women were entering other areas of the book trade, the number of women book publishers did not increase. In 1880, Florence I. Duncan (1849-1906) and Mary R. Heygate Hall (?-?) formed Duncan & Hall. The firm published at least one book, Ye Last Sweet Thing in Corners (1880), which was written by Duncan. Another woman publisher was Louise C. Boname (?-?), a French teacher in the city who wrote and published French language books for students beginning in 1896.

By the early twentieth century, book publishing in Philadelphia was dominated by a few well-established firms including Lea & Febiger and J.B. Lippincott & Co. In 1901, Lippincott moved to new offices at 227 S. Sixth Street, overlooking Washington Square. W.B. Saunders, Lea & Febiger, David McKay, and others eventually moved to the area as well, making it a center for publishing in the city. Perhaps the best-known book Lippincott published during this period was Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960). Lippincott was sold to Harper & Row in 1978, and then to the Dutch company Wolters Kluwer in 1990. The imprint is now called Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Lea & Febiger was sold to Baltimore-based Waverly Inc. in 1990. Waverly was bought by Wolters Kluwer in 1998 and became part of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Only a handful of new publishing firms formed in Philadelphia during the twentieth century. One of the most important was Running Press, founded by brothers Stuart and Larry Teacher in 1972 to publish nonfiction, children’s literature, and miniature books. Although acquired by New York’s Perseus Book Group in 2002, Running Press remained headquartered in Philadelphia.

While commercial publishing declined, universities became the major publishers of books in the Philadelphia region. University presses got their start publishing faculty scholarship, but soon expanded to publishing the work of other scholars. The University of Pennsylvania Press, established in 1890, began to regularly publish books in 1927, when Phelps Soule (1883-1968) was brought in from Yale University Press to act as a full-time editor. Under Soule, the press grew substantially, publishing books on a wide variety of topics from finance to medicine to bibliography to history. Other presses soon followed. The University of Delaware Press was founded in 1922, Rutgers University Press was founded in 1936, and Temple University Press began publishing in 1969. Saint Joseph’s University Press, primarily a publisher of books on Catholic history and culture, was founded in 1997. Although most books published by university presses are aimed at scholarly readers, some have found a wider audience. The Lincoln Reader, edited by Paul M. Angle and published by Rutgers University Press, was named a Book-of-the-Month Club selection in 1947.

Book publishing is one of Philadelphia’s oldest industries. Early on, Philadelphia printers like Benjamin Franklin and Mathew Carey understood the importance of books to a new nation. Especially during the first half of the nineteenth century, Philadelphia publishers played a crucial role in producing books for readers in remote areas across the United States. As the book trade grew, Philadelphia publishers successfully adapted to a changing market. Ultimately, Philadelphia’s book publishers became part of a national and international industry.

Ann K. Johnson is the Council on Library and Information Resources Postdoctoral Fellow at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. She holds a Ph.D. in history from the University of Southern California. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Now THIS Is A Publishing House! (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Benjamin Franklin, Writer and Printer (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- The Study and Practice of French in School for Beginners by Louise C. Boname (Google Books)

- The Living Book: New Perspectives on Form and Function (Digital Exhibit, Library Company of Philadelphia)