Treaty Negotiations with Native Americans

Essay

From the arrival of Europeans in the seventeenth century through the era of the early republic, treaties were an important tool in diplomacy between native nations and colonial Pennsylvania and later the nascent federal government. Treaties followed indigenous modes of diplomacy, into which colonists introduced, and imposed, the signing of treaty documents. However, treaty councils did not always culminate in a signed document. Indeed throughout the colonial period the term treaty described the process of negotiation and diplomacy, regardless of what such meetings produced.

Most famous in Pennsylvania was the legendary treaty of Shackamaxon negotiated by William Penn (1644-1718) and Tamanend, which produced no written record. In the colonial period, treaty councils took place in Philadelphia as well as native and colonial towns within and beyond the growing colony like Shamokin, Conestoga, and Lancaster. Treaties that secured large swaths of land for Pennsylvania at times occurred outside the colony, as with the Albany Purchase of 1754 and the New Purchase (1768) and Last Purchase (1784), both of which occurred at Fort Stanwix in New York. In 1758, at Crosswicks, Lenapes ceded rights to most of their lands in New Jersey to that colony’s government.

Councils were formal affairs steeped in native diplomacy, particularly Iroquoian ceremonies. As negotiators came together, they participated in the Wood’s Edge Ceremony, which acknowledged and ritually cleansed the arriving party from the perils of their journey and opened the lines of communication.

Over the ensuing days, or often weeks, Pennsylvania officials and native leaders exchanged speeches, gifts, and strings of wampum. While chiefs and colonial officials were key players, more often than not it was skilled orators who conducted negotiations, aided by interpreters. Metaphorical language, compelling voice and gestures, and command of an audience were all key to being a skilled native orator. Interpreters and intermediaries, or go-betweens, who relied on their trustworthiness excelled when they could translate not only between languages but also the cultural nuances that inflected negotiations. Colonial scribes recorded speeches from the interpreters and created minutes for treaty councils that offer historians a glimpse of the process and rhetoric of negotiation.

In the early decades of colonial settlement, treaties were often small local gatherings consisting of a few dozen participants. As the eighteenth century progressed, councils grew in size so that several hundred attendees would swarm the treaty grounds. At the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, commissioner Sir William Johnson recorded 2,200 native participants as the council opened. The vast concourse of spectators at treaties was important to the process itself, for native diplomacy relied on a notion of consensus. Indigenous onlookers became participants as they signaled their assent or discontent at the speeches that made up formal negotiations. The struggle for consensus also played out away from the formal and public arena as native leaders, officials, and intermediaries deliberated and worked out their differences in private. The search for common ground could protract the process, and treaty councils sometimes lasted for weeks.

While diplomats and intermediaries worked toward agreement on the issues at hand—land and boundaries were common concerns, but trade and, most importantly, war and peace spurred negotiations—colonial and native spectators busied themselves as well. Councils attracted traders of victuals, cloth, tools, munitions, and accessories. There were times for feasting, singing, dancing, and playing games.

By all accounts, native diplomats seemed impressed with their interactions with the Quakers, likely attributable to the Friends’ professions of peace and fraternal harmony in a period when Indian-colonist violence was foremost in the minds of native ambassadors. Quaker authority declined in Pennsylvania during the eighteenth century, however, as did their formal role in Indian-colonist negotiations. Indeed, following the Paxton Boys’ war to drive all Indians from the Susquehanna region, the belief that Quakers elevated native interests above those of backcountry colonists helped oust the “Quaker party” from the colonial assembly. Nevertheless, treaties of colonial officials with local Indian nations and Iroquoian nations dominated the colonial period even as relations between natives and the Pennsylvania government deteriorated—at times due to treaties themselves. Pennsylvanians’ crafty dealings in the 1737 Walking Purchase displaced and alienated their Lenape neighbors.

By the time the federal government ensconced itself at Philadelphia in the waning days of 1790, treaty negotiations in the city became more diverse and less conclusive. President George Washington (1732-99) and Secretary of War Henry Knox (1750-1806) were deeply concerned with Indian relations in Iroquoia, the Ohio country, and the southeast, rather than in Pennsylvania, where relatively few native people remained. Indeed, delegations to the city in the early 1790s primarily concerned the developing war in the west, where confederated nations of the Ohio country defeated the American army in 1790 and again in 1791.

During the capital’s tenure in Philadelphia, two dozen delegations arrived in the city to negotiate and fortify their ties to the federal government. While only the Cherokees signed a treaty in Philadelphia in these years, negotiations at the capital preceded or followed treaties elsewhere in the country. Visiting diplomats hailed from many nations, including Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Cherokees from the south; Wyandots, Delawares (newly residing in Ohio country), Ottawas, Chippewas, Potawatomies, Eel River, Weas, Kickapoos, Piankashaws, Kaskakias, Miamis, and Shawnees from the west; and Mohawks, Senecas, Oneidas, and Onondagas from the north.

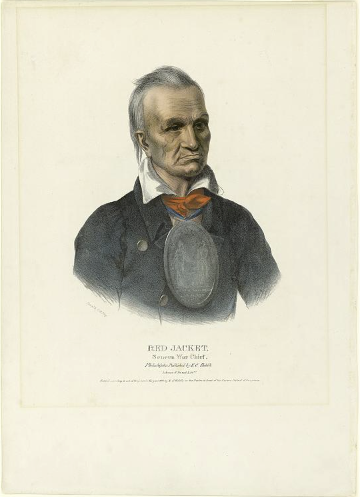

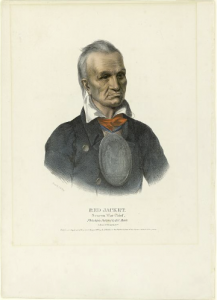

Like earlier treaty councils, formal speeches, or talks, formed the core of negotiation between delegates and the federal government. The Seneca Red Jacket (c.1750-1830), was among the most famous orators (native or white) in the early republic, and his speeches from treaty councils were recorded and published in newspapers around the country. However, negotiations in the capital were much smaller than those from earlier decades. The largest visit in the 1790s consisted of forty-nine Iroquois who attended Philadelphia in 1792, though no treaty was signed at the conclusion of negotiations. However, the average was fewer than a dozen. Deliberations with the president and secretary of war were protracted, with days sometimes intervening between the exchanges of talks, prolonging negotiations, as in the past, over weeks and sometimes months.

During that time, native negotiators toured many cultural and civic sites, such as theaters, museums, churches, and the new waterworks. Several of the iconic prints of William Birch (1755-1834) captured native visitors moving about the city. As they negotiated the urban landscape, diplomats engaged with Philadelphians informally in streets and taverns and in more formal meetings with members of the Quaker Indian Committee and local and foreign dignitaries. Through these meetings long-standing relationships were solidified and new ones forged between the Friends and distant nations like the Creeks and Cherokees.

Gifts and hospitality remained crucial to the treaty negotiations, as reflected in President Washington’s 1792 address to Iroquois diplomats “that during your residence here you should be well fed, well lodged and well cloathed, and that presents should be furnished.” Gifts varied but almost always included clothing and other textiles, and guns and ammunition were common. Cast in large lots at the mint in Philadelphia, medals were a ubiquitous gift to indigenous diplomats. Rank determined the size of medals that the diplomats received, as the most prominent leaders received the largest medallions.

With the transfer of the federal capital to Washington in 1800, Philadelphia’s role in treaty negotiations diminished. Nevertheless, native people continued to come through the city on their way to and from Washington, often to exchange talks with Quaker allies and to take in the sights of one of the nation’s most vibrant cities.

Stephanie Gamble received her Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University in 2014 for her dissertation, “Capital Negotiations: Native Diplomats in the American Capital, 1789-1837,” and is the author of “A Community of Convenience: The Saponi Nation, Governor Spotswood, and the Experiment at Fort Christanna, 1670-1740,” in Native South (2003). She is a Learning Specialist at the University of Kansas Libraries and is working on a history of Native speeches and cultures of diplomacy in the capitals of the early American republic. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University