Printing and Publishing

By James J. Wyatt | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

From the late seventeenth century to the mid-twentieth century, Philadelphia’s printing and publishing industry was a central component of the city’s evolution from “Green Country Town” to “Cradle of Liberty” to “Workshop of the World.” Growing their operations from small do-it-all shops into large fully mechanized publishing houses, Philadelphia’s printers and publishers capitalized on the broad social, political, and economic changes that reshaped the region and nation between the revolutionary and industrial periods. Men such as Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), Mathew Carey (1760-39), William Swain (1809-68), and Cyrus H.K. Curtis (1850-33) utilized pioneering sales and marketing techniques and technologically advanced printing methods while founding some of the nation’s largest publishing companies and establishing Philadelphia as one of the most historically significant publishing centers in the United States. However, during the post-World War II era, publishers in the Greater Philadelphia area experienced an extended period of upheaval that resulted in the sale or closing of several of the most famous and venerable companies.

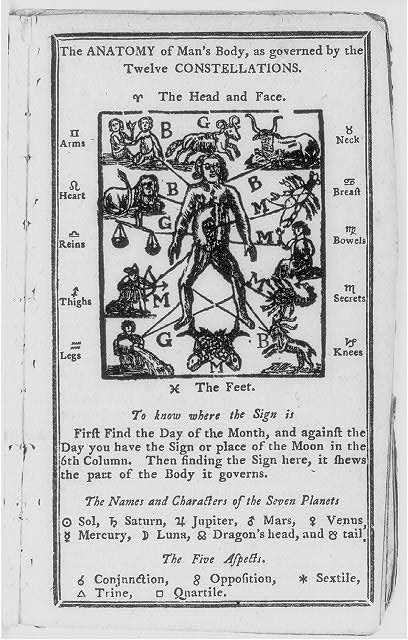

As Philadelphia evolved into America’s largest port city during the eighteenth century, the number of printer-publishers operating within it grew from one in 1683, to nine in 1740, and eventually to fifty-one in 1785. Philadelphia’s colonial printers generally located their shops close to highly trafficked commercial streets and squares, and most cobbled together a living by performing multiple tasks. Virtually all found their bread and butter in fee-based print jobs for clients. Colonial printers published their own works and the works of others in the form of almanacs, pamphlets, and newspapers, and they often operated as retailers, selling supplies and imported books from their shops.

Of the many printers who utilized this business model, none was more successful than Benjamin Franklin. Franklin understood that the key to success lay in finding steady revenue streams and access to new markets. Shortly after establishing his print shop, Franklin negotiated the purchase of a newspaper and acquired a lucrative government printing contract. He shrewdly renamed the paper the Pennsylvania Gazette and changed its format to include more news and entertainment, thereby making it one of the more popular publications in the city and a continuing source of advertising revenue. Franklin used the profits from these endeavors to finance one of the first printing networks in the American colonies, training a coterie of apprentices and helping them establish their own print shops in outlying parts of the region. The network of printers enabled Franklin to sell periodicals and books for which he was the publisher to a larger audience, and through it, works like the annual Poor Richard’s Almanac became widely popular. Franklin’s far-reaching and multifaceted business was enormously successful, and it served as the prototype for building a lasting printing and publishing company in the American colonies.

Do-it-all print shops of this sort predominated in Philadelphia until the early nineteenth century, when market changes precipitated the separation of the city’s printers and publishers into two distinct groups. Philadelphia’s service as the nation’s interim capital during the 1790’s sparked this transition, as several local printer-publishers dedicated themselves to producing crusading, politically partisan newspapers. Most of these papers, save Benjamin Franklin Bache’s (1769-98) Philadelphia Aurora (1789-1824), did not last much past 1800. However, in the ensuing decades, entrepreneurs like Mathew Carey furthered this process by building publishing companies that specialized in producing works for specific segments of the American marketplace.

Growing Demand for Bibles

For his part, Carey took advantage of the growing demand for religious reading materials during the period by focusing his company’s energies on the production of Bibles. The publisher correctly theorized that producing a small assortment of easily printed works for a growing segment of the market would reduce much of the speculation and risk that had long been an intrinsic part of publishing and would provide consistent profits. Carey also pioneered the use of traveling salesmen and book peddlers to carry his products far beyond the Philadelphia region. These initial successes made Carey a wealthy man and helped prove that publishing, by itself, could be lucrative. Of course, those successes also invited competition. In later years, denominational publishers, including the Baptist General Tract Society (1826) and the Lutheran Publication Society (1855), among others, emerged and helped make Philadelphia a hub of religious publishing.

Technological innovation facilitated the further development of Philadelphia’s print-based industries. Area printers and publishers continually sought increased profits through faster and cheaper production methods. During the 1820s, both began experimenting with steam-powered presses and stereotyping, a process by which metal plates cast from molds of set type were used for printing. Early steam-powered presses tripled and quadrupled print speeds while reducing manpower costs, thereby increasing profits for printers and publishers alike. Stereotyping saved publishers money while enabling them to more precisely respond to the market. The plates could be stored and used to print additional copies of books whenever necessary, thus cutting composition costs and alleviating the need to speculatively invest significant capital in unproven publications. Moreover, the plates could be copied and sold to other publishers for the later publication of licensed editions of books.

Book publishers readily benefited from these technological advances. However, it was in the realm of newspaper publishing that they had, arguably, the most transformative impact. Steam-powered presses enabled newspaper publishers to reduce the price of their papers to a penny, thus making their products affordable to a much wider segment of the reading public. Philadelphia became one of the first cities in America to boast a penny paper when Dr. Christopher Columbus Conwell (unknown-1832) founded The Cent in 1830. Conwell’s paper was short-lived, but within a few years William M. Swain’s Public Ledger (1836) had replaced it. Like most penny papers of the 1830s, the Public Ledger played to working-class readers by including sensational headlines and titillating reports, local news and human-interest stories, and entertainment features. It was an immediate success. Within two years of its founding, the Public Ledger’s daily circulation exceeded 20,000 readers. The paper’s popularity was such that Swain was regularly forced to upgrade its equipment to keep up with demand. A year after beginning with a single-cylinder steam press, Swain added a two-cylinder press to his operation, tripling his printing capacity. Less than a decade later, with the Public Ledger among the most read papers in America, Swain had the first type-revolving press installed in his shop. By the 1850s, the publisher had the capacity to produce more than 20,000 Public Ledgers an hour.

Technology Fuels Magazines

Advanced printing technologies also facilitated the development of a nascent magazine publishing industry in Philadelphia during the 1830s. Publishers like Louis A. Godey (1804-78) utilized powered steam-presses and stereotypes in the production of high-quality monthly publications. However, unlike the penny presses, magazines such as Godey’s Lady’s Book (1830-78) targeted a narrower readership. Godey sought readers among the rising numbers of middle-class women in the United States, setting high subscription rates to ensure the periodical’s exclusivity. Following the 1837 appointment of Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879) as editor, the magazine emerged as a taste-making, trendsetting journal with national appeal. Hale filled the magazine with poetry and literary short stories by female and male American authors alike, and she regularly incorporated articles and columns dedicated to women’s topics. It was under Hale’s leadership that Godey’s gained notoriety for the hand-tinted fashion plates at the beginning of each issue. During the 1840s and 1850s, Godey’s became required reading for most women aspiring to or claiming middle-class status. Its circulation climbed accordingly, surpassing 150,000 in the 1850s.

By the mid-nineteenth century, Philadelphia had grown into one of America’s foremost printing and publishing centers, surpassed only by New York City and rivaled only by Boston. In the latter half of the century, the city’s maturation into a densely populated industrial metropolis enabled the continued success and further expansion of these industries.

Newspaper publishers benefited immensely from the centralization of people, industry, and commerce within the city’s boundaries. Since newspapers were then the only sources of national, regional, and local news, many people read more than one each day. In addition, the emergence of large downtown department stores such as Wanamaker’s brought increased advertising revenues. Moreover, the development of ever more technologically advanced printing presses and methodologies enabled publishers to produce larger newspapers faster while keeping costs down. By the 1890s, Philadelphia supported thirteen daily newspapers whose cumulative daily circulation exceeded 800,000. Among the papers competing with the Public Ledger for morning readers were the Record, Inquirer, and North American. Evening dailies, which were actually printed in the afternoon to service the city’s working class, included the Item, Call, Herald, Telegraph, and Evening Bulletin. Unsurprisingly, they varied in size and tone, and some, like the Inquirer, which was widely recognized as an outspoken mouthpiece for the bosses that ran Philadelphia’s Republican machine, gained notoriety for their political positions.

Philadelphia’s newspaper industry was bolstered by the emergence of numerous ethnic presses. Newspapers catering to immigrants were nothing new in the city. Ben Franklin’s German language paper, Philadelphische Zeitung had been founded in 1732, however, the city’s varied and rapidly expanding immigrant population prompted the emergence of dozens of ethnic papers during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Many lasted but a little while, but those that survived and prospered usually published on a weekly or semiweekly basis. Publications such as the Italian Voce Della Colonia (1893-1918), the Polish Patryota (1889-1955), and German Philadelphia Tageblatt (1877-1944) gained popularity by serving as the voices of their communities. They translated important information for non-English speaking readers, carried news of the homeland, and helped establish community bonds by promoting ethnic events and organizations. Some, like the Jewish paper, Idishe Welt (1914-1942) were considered radical or revolutionary. During this period, the Philadelphia Tribune (1884-) was founded to perform similar functions for Philadelphia’s African American community.

Low Subscription Rates

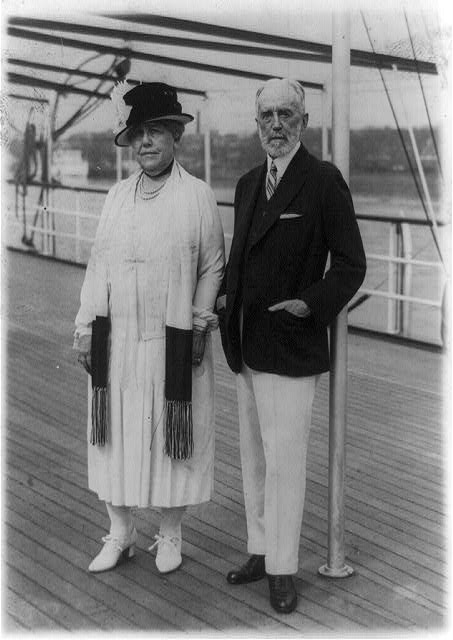

Also taking advantage of the changes wrought by industrialization were the city’s magazine publishers. Among the industrial era’s most successful publishers, Cyrus H.K. Curtis (1850-1933), kept subscription rates low and interest high by selling enormous amounts of advertising space and incorporating helpful and informative content within each magazine. The Ladies Home Journal (1883) frequently blended columns addressing fashion, cooking, and homemaking with articles penned by social reformers such as Jane Addams (1860-1935). Under the guidance of famed editor Edward Bok (1863-1930) and Curtis’ wife, Louisa Knapp Curtis (1852-1910), the Journal became the first magazine to achieve a circulation of one million copies per issue in 1904. Curtis used the profits garnered from the Ladies Home Journal to purchase the Saturday Evening Post in 1897 and then transformed it into America’s most popular magazine. Though the magazine became famous for the Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) illustrations that graced its covers, the Post initially gained popularity as a general-interest magazine that published poetry, short stories, and news. Seemingly including a little something for everyone, the Post attracted readers and advertisers en masse. By 1910, the magazine’s circulation stood in excess of one million, and its annual advertising revenues topped $5 million.

Flush with success, Philadelphia’s publishers upgraded their presses and facilities during the first half of the twentieth century. Cyrus Curtis’ enormous Georgian Revival headquarters was completed in 1910 at the corner of Sixth and Walnut Streets. Along with the neighboring J.B. Lippincott Company and Lea & Febiger Publishers, the Curtis Building helped anchor Philadelphia’s publishers’ row for decades. During the same period, newspaper publishers James Elverson Jr. (1869-1929) and William L. McLean (1852-1931), respectively, moved the Inquirer and Evening Bulletin into gleaming new homes that provided the same advantages, centralized operations and faster production.

Expansions and Consolidations

Philadelphia’s printing and publishing industries continued to prosper well into the 1950s despite the tumult caused by two world wars and the Great Depression. Competition and market changes reduced the number of daily newspapers operating in the city from thirteen to three by mid-century, but the Evening Bulletin thrived and consistently ranked among the nation’s most widely read papers with a daily circulation that often exceeded 700,000. In 1955, the Bulletin Co. opened one of the most technologically advanced newspaper plants in the world, with presses capable of producing near one million newspapers an hour, near Thirtieth and Market Streets. In 1946, Inquirer publisher Walter Annenberg (1908-2002) founded Triangle Publications Inc. and began branching into magazine publishing and broadcast media. By the late 1950s, Triangle’s stable of publications included the Inquirer, the afternoon tabloid Daily News, Seventeen magazine, and TV Guide, which grew into the nation’s largest weekly periodical by the 1970s. The publications provided the foundation upon which Annenberg built Triangle into one of the nation’s largest and most profitable multi-media corporations.

Other Philadelphia publishing stalwarts continuing their successes into the postwar era included the Curtis Publishing Co., which entered the entered the period as one of the largest and most profitable in the world and broke ground in 1946 on an enormous new production facility in Sharon Hill, Pa. The facility, with the capacity to produce more than a million magazines a day, introduced the first successful four-color “perfecting” presses capable of printing rolls of paper on both sides simultaneously. Although Philadelphia’s book publishers were not able to turn back New York’s emergence as the nation’s preeminent publishing center, specialized book publishing, particularly in the areas of science, medicine, education, and religion, remained a successful hallmark of the city’s industry. As one of the nation’s largest book publishers, the J.B. Lippincott Company maintained branch offices in New York City, London, and Canada and successfully expanded beyond medical publishing into elementary and high school textbooks, reference materials, and religious works. In 1961 Lippincott acquired A.J. Holman Company, a noted a publisher of Bibles and religious books, and shortly thereafter opened a 140,000-square-foot distribution center on Roosevelt Boulevard. By 1975, the company’s gross sales exceeded $45 million.

Despite these gains, Philadelphia’s publishers were not immune to the larger market shifts that transformed the national publishing industry during the postwar era. Beginning in the 1960s and carrying forward into the early twenty-first century, the growth of suburban areas and emergence of new communications mediums contributed to a prolonged wave of consolidations and closings among book, magazine, and newspaper publishing companies across the nation.

Philadelphia felt these shifts acutely. During the 1950s, a diverse array of suburban daily and weekly newspapers capitalized on the outflow of people and retailers from the city and established a dominant hold on the region’s lucrative suburban markets by siphoning circulation and advertising revenues from their urban counterparts. Outside corporate ownership also increased during the postwar period. In the 1960s, the Gannett newspaper chain purchased several daily and weekly newspapers in southern New Jersey. In 1969, Annenberg sold the Inquirer and Daily News to Knight Newspapers, and in 1978 Harper Row Publishers Inc. acquired J.B. Lippincott. The company was sold to Wolters Kluwer, a Dutch company, in 1990 for $250 million.

Many Philadelphia publishers and publications did not survive this shifting landscape. During the 1960s, changing reader tastes and increased competition from magazines like Life and Look as well as television contributed to the rapid decline in the popularity of Curtis Publishing’s periodicals. A series of poor management decisions compounded the company’s dwindling profits and led to its rapid collapse by the end of the decade. In 1969, the Saturday Evening Post ceased publication and the Ladies Home Journal was sold. Among the city’s remaining newspapers, the Evening Bulletin experienced a prolonged, though no less stunning, slide. Facing increased competition from the Knight-backed Inquirer and thriving suburban daily and weekly newspapers like the Camden Courier-Post and the Bucks County Courier Times, the paper suffered declining circulation and advertising revenues for almost two decades. In 1980, the McLean family sold the paper to Charter Media Company, and in 1982 the Evening Bulletin’s doors were shuttered for good, leaving the city without a large independently-owned daily newspaper. In 1990, Lea & Febiger, a prominent Philadelphia publisher of scientific books with historic roots extending to Mathew Carey’s publishing company, was purchased by Waverly Press of Baltimore and ceased operations.

The closings and corporate takeovers of the late twentieth century rocked Philadelphia’s printing and publishing industry, but they did not fully cripple it. The shifting market conditions created opportunities for some established publications to expand and for new companies and publications to emerge. While many of Philadelphia’s established ethnic and religious newspapers failed to survive past the 1950s, some, like the Jewish Exponent (1887-), grew into regional publications. The Philadelphia Gay News was established in 1976 to service the city’s growing LGBT community, and two free alternative weeklies, Philadelphia Weekly (1971-) and the City Paper (1981-2015) quickly gained popularity. Additionally, the influx of new immigrant groups into the region fostered development of new ethnic newspapers. Al Día, a free tabloid serving Latino communities, began publishing in 1992, and Metro Chinese Weekly appeared in 2007 to serve Asian-Americans.

In the realm of book publishing, the long tradition of religious publishing in the Philadelphia area continued at two publishers with roots in the nineteenth century, Judson Press (formerly the Baptist General Tract Society), the publishing ministry of American Baptist Churches, USA, and the Jewish Publication Society. Additionally, several independent publishing companies, including Running Press Book Publishers (1973), Camino Books (1987), and Quirk Books (2002) began operation in Philadelphia during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Running Press, founded by brothers Lawrence (1941-2014) and Stuart “Buz” Teacher (b. 1947), published how-to, self-help, and other non-fiction works across the globe. Beginning with a headquarters at 125 S. Twenty-Second Street, the Running Press expanded to include branch offices in New York and London before its purchase by the Perseus Book Group in 2002. Quirk Books gained recognition for publishing several New York Times best-sellers, including Ransom Riggs’ (b. 1979) Miss Peregrin’s Home for Peculiar Children (2011).

Although the region’s printing and publishing industry in the early twenty-first century no longer maintained the lofty status it once enjoyed as one of the nation’s foremost centers for the printed word, the region’s publishers continued to carry on the independent traditions established by Philadelphians like Benjamin Franklin.

James J. Wyatt is the Director of Programs and Research at the Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education at Shepherd University and President of the Association of Centers for the Study of Congress. He is curator of the traveling exhibit “Robert C. Byrd: Senator, Statesman, West Virginian” and co-curator of the collaborative digital exhibit The Great Society Congress, an ACSC project. Wyatt earned a Ph.D. in History at Temple University. His doctoral dissertation, “Covering Suburbia: Newspapers, Suburbanization, and Social Change in the Postwar Philadelphia Region, 1945-1982,” focuses on the emergence of suburban newspapers in the Philadelphia metro area following World War II.

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History