Quaker City

Essay

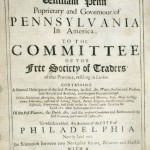

William Penn (1644-1718), the founder and proprietor of Pennsylvania, had high hopes for Philadelphia. He wanted the city to become the economic and moral hub and showpiece of the nearly 50,000 square miles that he had been granted as Pennsylvania (Penn’s Woods). Penn outlined his radical notion when he advertised the city for settlement in 1681: he intended to construct a physical, economic, political, and religious environment in which divine virtue would tame the human tendency for sin and corruption. His mission would leave an indelible imprint on the politics, economics, culture, and land-use of the Delaware River valley region and Philadelphia, the Quaker City.

As a member of the Religious Society of Friends of the Truth (Quakers), a British Christian splinter group, Penn shared in the belief that Christ’s arrival was occurring in his time. In response, it behooved people to live up to Christ’s presence. Though there is no evidence that Penn used the term “The Quaker City” for Philadelphia, he drew inspiration from Quaker founder George Fox, his mentor, as he imagined a communal environment where people would live in a way that “taketh away the need for all wars.”

Penn’s religious faith led him to his conviction that a prudently-designed and carefully-monitored physical environment, governed by a rational and nurturing political and economic leadership, would promote a salubrious community life. To that end, he sent a city planner to lay out the city’s grid and to negotiate with the region’s prior inhabitants before new settlers arrived. In addition Penn’s carefully-crafted Frame of Government for Pennsylvania allowed for a greater religious liberty than had been known in the Old World. Penn’s plan also called for responsible citizen participation in government, and—importantly—a prohibition against a military system.

Having lived through the Great Fire in London in 1666, Penn envisioned that Philadelphia—a “Green Countrie Towne” that would “always be wholesome and never be burnt”–would be the centerpiece of Pennsylvania. Prayerfully, contemplated his project: “And Thou Philadelphia the virgin settlement of this province named before thou wert born, what care, what service, what travail have there been to bring thee forth …. O that thou mayest be kept from the evil that would overwhelm thee…” With careful attention to street layout, architecture, and urban design that emphasized community gathering places and “greene” parks, Penn hoped to engender an atmosphere that would encourage high morality and community responsibility.

The Road to Philadelphia

Penn did not envision his green country town as only an isolated, idyllic outpost for Quakers. Aiming to attract non-Quaker as well as Quaker land-speculators, and others whom he described as “low in the world” (economically, religiously, or politically oppressed), Penn sent representatives to publicize his project widely across northern Europe. Promising economic prosperity and religious freedom, as well as governmental fairness, he broadcast his ambitious plans that Philadelphia would become a “Great Towne,” a leader in the burgeoning Atlantic commercial world. Through careful management of land sales and values, Penn also aimed to have Philadelphia remain the hub of a regional economy.

Penn’s description of the foundations of his Quaker governance worked so well that within a few decades of its founding, non-Quaker residents outnumbered the Quakers in Philadelphia. Despite their minority status, however, the power, influence, legacy, and legend of Quakers’ ideals and values remained an enduring theme in Philadelphia’s development. Though many Philadelphia Quakers withdrew from government service rather than participate in the Seven Years’ War (1756-63), they found other ways to advocate for their particular brand of integrity and community responsibility, including active civic engagement (especially in philanthropy and education); innovative entrepreneurship; attention to integrity, philanthropy, and fiscal responsibility (Quakers call it “stewardship”); and religious and social fairness. By the 1760s, the Quaker reputation for integrity was so widespread that Benjamin Franklin (1706-90)–who worked tirelessly and imaginatively to improve urban life, with projects as diverse as news publishing, mail delivery, improved street lighting, volunteer fire companies, and the Franklin stove—allowed people to think he was a Quaker, even though he was not.

The economy of Philadelphia grew vigorously. Shippers and traders from across the Atlantic world made deals with farmers and entrepreneurs from the city’s back country, who hauled their wares to Philadelphia’s ports along the well-planned roads. Indeed, by 1750, Philadelphia’s Quaker-dominated commercial energies had made it the second most important city in the British empire, and by the 1790s, Quaker entrepreneurship had fostered the nation’s first government-backed toll road from Lancaster to Philadelphia. Within a few years, Quakers Josiah White (1781-1850) and Erskine Hazard (1789-1865) made plans to augment this infrastructure with a network of canals. Thus, Quaker entrepreneurship helped to situate Pennsylvania with an economic preeminence that it yielded to New York only in the 1820s–and only grudgingly.

Urban Vision Writ Large

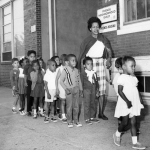

No one knows who originated the quip that “Quakers came to America to do good, and did very well.” But the combination of opportunity and frugality did, for a number of Quakers, bring great wealth. In response, worried that wealth would bring the temptations of moral flabbiness, Quaker leaders encouraged each other to donate the “excess” to worthy community concerns. Thus, beginning in the eighteenth century, Quaker public-good enterprises became ubiquitous. Philadelphia Quaker entrepreneurs were early participants in establishing a lending library (1731); a university (1740); the nation’s first professional medical facility (1751) an anti-slavery network (1770s); canals (1820s); museums and historical societies (1820s); national railroad systems (1830s); investment-banking houses (1830s); and the nation’s first zoo (begun in 1859, and completed fifteen years later). Other nineteenth-century Philadelphia-Quaker initiatives included the nation’s first hospital aimed at offering “tender, sympathetic attention” to the mentally ill (1813); a visionary urban prison system focused on reform, rather than punishment (1829); and a medical college for women (1850s). Beginning with the first Quaker school in the 1680s, the number of Quaker educational institutions mushroomed: as of 2014, more than three dozen Quaker-run schools were operating in the Philadelphia area. Quakers’ “fairness” initiatives also included schools for African Americans (dating from the 1750s) and a number of multi-racial, multi-class cooperative housing ventures (1940s-1960s).

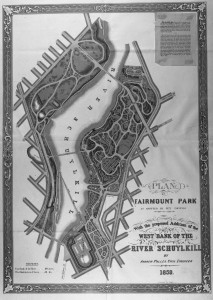

In these and other projects, Quaker investors, architects, and engineers played pivotal roles, often working behind the scenes to consciously echo Penn’s dreams of a responsible citizenry. Eighteenth-century master builder Samuel Rhoads (1711-84) exemplified this posture, serving as a designer of the colony’s state house, as a founding member of the nation’s first lending library and first insurance company, and as a director of Philadelphia’s almshouse and hospital. In 1800, Quaker leadership helped shape the development of America’s second municipal water works, located on the Schuylkill River. In the 1840s, to protect the quality of the water supply, Quakers spearheaded the city’s acquisition of a number of Quaker estates along the banks of the river. This project, which grew into the massive Fairmount Park, also resulted in the establishment of America’s first zoo in 1874.

Throughout the nineteenth-century, the city’s urban design and infrastructure projects were often dominated by Quaker architects and planners, many of whom felt bound by their forebears’ forward-looking vision. Horace Trumbauer (1868-1938), for example, apprenticed with an architectural firm owned by Quakers D.W. and W.D. Hewitt. This firm carried on Quakers’ racial-justice heritage by hiring Julian Abele (1881-1950), Philadelphia’s first African American architect. Quaker Edmund Bacon (1910-2005), who served as director of Philadelphia’s City Planning Commission from 1949 to 1970, also took inspiration from his heritage as a descendant of one of William Penn’s first purchasers. Lecturing frequently on the importance of attractive public spaces, Bacon remained focused on the goal of keeping the city’s economy and infrastructure vibrant, as well as welcoming to a broad mix of inhabitants. Philadelphia’s iconic “Love Park”—which Bacon envisioned while still a young student in architecture school—followed on the tradition of a “greene countrie towne.”

Bacon also embraced the long tradition of Philadelphia as a “Great Towne.” He was fond of displaying the 1794 “Map of Philadelphia and Environs” (by A.P. Folie), with its roadways radiating out from the city, but labeled “the road to Philadelphia,” which testified to the city’s intention to remain a regional hub. So, too, said Bacon, did the construction of the mid-twentieth-century Schuylkill Expressway, which gave suburban dwellers relatively easy access to the city.

The Enduring “Quaker City”

The origins of the nickname of “The Quaker City” are murky, but a surprising amount of Penn’s vision has stood the test of time. Of course, the “Quaker” legacy could not inoculate Philadelphia against the typical urban stresses—political corruption, budget struggles, inter-group tensions, employer/employee conflicts, infrastructure challenges, and crime. However, by the mid-nineteenth century, when novelist George Lippard chose the title The Quaker City for his tale of urban corruption and debauchery– highlighting the disjunction between Quaker vision and urban reality–most readers understood the irony of the fact that the novel included only one Quaker character: indeed a man of integrity, but a man who makes only a brief appearance, as he is exiting Philadelphia.

Nevertheless, in modern times, many of the city’s institutions, businesses, and citizens continued to be stamped by both the positive and negative imagery attributed to the stereotypical “Quaker,” even when the term “Quaker” has little or no relationship to the Religious Society of Friends. As early as 1859, when entrepreneur the “Quaker State” oil company was established by a non-Quaker to harvest and distribute Pennsylvania’s petroleum products, the advertisers and customers understood the appeal of Quakers’ reputation for honesty and integrity. Nearly two decades later, the image of William Penn found its way to the Quaker Oats box, appropriated by an Ohio cereal-maker who had read about Quakers. Philadelphia became home to the University of Pennsylvania’s football team “the Quakers,” and to the William Penn Foundation, a well-endowed organization providing grants to enrich “cultural expression, strengthen children’s futures, and deepen connections to nature and community.” Established in the 1940s, and long known as the Haas Foundation, the William Penn Foundation renamed itself in 1974, explaining the change as reflecting its desire to commemorate Penn’s “pursuit of an exemplary society and understanding of human possibilities.”

Still, the Philadelphia region has been the site of many Quaker “firsts,” including Haverford College (1833)—the world’s first Quaker college—and dozens of Quaker schools and other institutions for social “improvement.” The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), perhaps the best-known Quaker organization, was born in Philadelphia during World War I and its central office has remained in the city. Widely known for its non-partisan relief projects in war-torn regions of the world, and for its partnership with Amish, Mennonite, and United Brethren denominations in designing alternative, nonviolent service instead of military service (conscientious objection), the AFSC accepted the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the Religious Society of Friends in 1947. When two representatives from “the Quaker City” traveled to Stockholm to accept the award, many Philadelphians took pride in the city’s Quaker heritage.

But there is plenty of negativity in the “Quaker” imagery, too. Philadelphians have struggled to live down a reputation for being boring and resistant to change, as well as insular and self-righteous—characteristics that are often attributed to the socially- and economically-conservative Quaker ethos. For example, conservative alcohol-control laws constrain many Philadelphia-area municipalities, and amidst the modern proliferation of skyscrapers, Philadelphia city planners long clung to the notion that no part of Philadelphia’s skyline should rise higher than the statue of “Billy Penn” that stands atop City Hall.

In the twenty-first century, fewer than 15,000 Quakers live in the Philadelphia area, yet the notion of the “Quaker City” survives. Can the mystique and tradition of “the Quaker City” survive the skyline that finally, in the 1990s, eclipsed Billy Penn’s hat?

Emma Lapsansky-Werner is a Quaker, a Professor of History at Haverford College, and a happy resident of the Philadelphia area for more than a half-century. She began researching and writing about the city in the 1960s, and has since has lectured and published on many aspects of Philadelphia’s history. (Author information current at time of publication.)