National Register of Historic Places (Sites)

Essay

The Philadelphia region’s early settlement and political and industrial dominance throughout the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries left a tremendous physical presence on the landscape, both above and below ground. Many of these places have been added to the National Register of Historic Places, a list of buildings, neighborhoods, objects, structures, and sites throughout the United States that are considered historically significant and worthy of preservation.

The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 established the National Register as part of a broader set of federal policies and programs aimed at identifying and preserving properties of historical, cultural, and architectural significance. The act responded to the loss of historic properties in the mid-twentieth century, when federal highway and infrastructure projects and urban renewal significantly impacted or destroyed many historic neighborhoods in the nation’s oldest and densest communities. In Philadelphia, when the construction of I-95 along the Delaware River through some of the city’s earliest neighborhoods, including Pennsport, Society Hill, Old City, and Frankford, demolished thousands of the city’s earliest buildings, no policy required planners to consider the historic value of these resources when determining the route.

That lack of policy changed in 1966. The National Historic Preservation Act, the first comprehensive effort to establish historic preservation as a public policy, required federal agencies to consider the effects of their projects on historic and archaeological resources and take steps to avoid, minimize, or mitigate those effects before implementing projects. To facilitate that consideration, it also established a list of properties deemed historically significant that agencies had to take into account in their plans—the National Register of Historic Places, maintained by the National Park Service in partnership with State and Tribal Historic Preservation Offices. Listing in the National Register came to be a sign of cachet and prestige, and a prerequisite for many government grant programs and tax incentives for historic preservation. The act did not, however, obligate or restrict private owners from using, altering, or even demolishing private property with private funds.

Properties listed in the National Register, all exemplifying some significant aspect of local, state, or national history, could be buildings or building complexes, districts composed of dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of properties, structures such as bridges, objects such as monuments or fountains, or sites, including cemeteries, battlefields, and archaeological sites. Generally speaking, properties were required to be at least fifty years old to be considered eligible for the National Register, although buildings from more recent time periods that have demonstrate “exceptional significance” have also been listed.

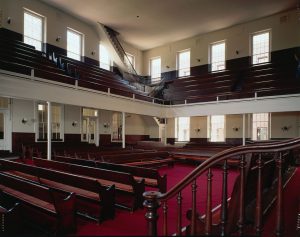

Early listing efforts in the Philadelphia area focused on the region’s oldest and grandest places, including individual buildings scattered throughout Germantown, Society Hill, and Center City. The first district listed in Pennsylvania was the Plymouth Meeting Historic District in Montgomery County in 1971, centered on the Plymouth Friends Meeting and Abolition Hall. In the 1980s more than 150 of the city’s public schools built prior to 1938 were listed as part of a thematic nomination.

By the twenty-first century the National Park Service encouraged diversifying the National Register to be more reflective of the full spectrum of American cultures and time periods. Later Philadelphia listings included diverse resources such as factories associated with the textile industry in Kensington; Mt. Zion A.M.E. Church in Chester County, the site of school desegregation organizing in the 1920s; and Mill-Rae, the home of Rachel Foster Avery (1858–1919), a lieutenant of Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906) in the woman suffrage movement, in the city’s Somerton neighborhood.

In southern New Jersey, the National Register listed places associated with Walt Whitman (1819–92), early Quaker communities, the Battle of Red Bank, and many residential and commercial districts such as Cape May and Haddonfield. Industrial resources, including the entire length of the Delaware & Raritan Canal, Batsto Village, and the Gloucester City Water Works Engine House, also joined the list.

Northern Delaware added numerous districts and individual properties to the National Register, including many neighborhoods in Wilmington, such as the West Ninth Street Commercial District, listed in 2008. Listings outside the city illustrated other themes of the region’s history. The National Register accepted for listing Owl’s Nest Country Place, the 1915 Tudor Revival country house of Eugene duPont Jr. (1873–1954) in Greenville, and the Iron Hill School #112C, built in 1923 for African American students and paid for by a trust established by Pierre S. duPont (1870–1954).

To be listed on the National Register, a property must both have significance and retain integrity. Significance can be defined in one of four ways: in relation to events or patterns of history, significant persons, architectural or engineering significance, or archaeological potential. Integrity is established by a combination of the location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association of a property and the relationship of those aspects to the property’s historical or architectural significance. Despite its name, the National Register has listed not only places of national significance but also properties considered locally significant, with importance and value to their communities or regions. The register also includes places of all ages, sizes, and types.

The National Register is not a static list, but rather a system that allows for the ongoing documentation and evaluation of new properties. Given the many layers of history in the region, many previously underappreciated places, communities, and stories have been deemed worthy of listing in the National Register.

Cory Kegerise is the Community Preservation Coordinator for Eastern Pennsylvania at the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office. A native of Berks County, he lives in Philadelphia and holds a master’s degree in Historic Preservation from the University of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Nomination and Report Library (Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia)

- National Register of Historic Places

- Philadelphia Register of Historic Places

- National Register of Historic Places, Philadelphia County

- Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office

- New Jersey State Historic Preservation Office

- Delaware State Historic Preservation Office