Popular Music

By Jack McCarthy | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Philadelphia has been a key center in popular music—music appealing to popular tastes—since the late eighteenth century and at several points in history has been recognized as a world leader in the genre. Shaped by the rich musical traditions of its numerous ethnic and religious groups, the city produced many widely popular and influential artists and styles.

Music in early Philadelphia developed slowly because the city’s founders, members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), shunned all music. The Quaker influence diminished considerably in the mid-eighteenth century, however, and a public musical life began to emerge. Most popular music in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Philadelphia derived from Britain: songs from English musical theater and popular and folk songs from the British Isles. Other nationalities and ethnic groups practiced their own popular music as well, largely out the mainstream.

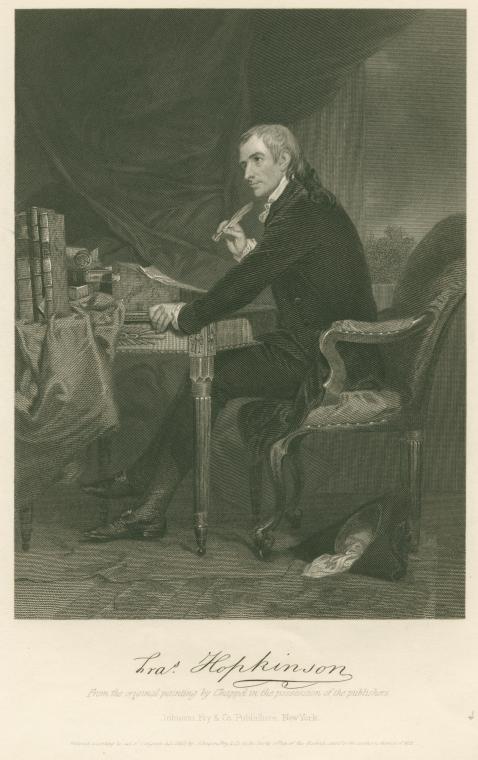

The first Philadelphian to contribute significantly to popular music, Francis Hopkinson (1737-91), America’s first “poet-composer,” wrote songs and performed locally in addition to being a signer of the Declaration of Independence and influential figure in the city’s political and civic life. Hopkinson’s song “My Days Have Been So Wondrous Free,” written in 1759, is generally considered the first secular song composed by a native-born American. (Never published, the song exists only in manuscript form at the Library of Congress.) In 1778, Hopkinson wrote two popular Revolutionary War songs, “Battle of the Kegs,” a satirical song mocking the British army then occupying Philadelphia, and “The Toast,” a song praising George Washington (1732–99) and the American cause. In 1788, Hopkinson published Seven Songs for the Harpsichord or Forte Piano, the first set of secular songs published in the new United States. Although significant historically, there is no indication that these songs, written in genteel English style, became broadly popular or were heard beyond the drawing rooms of Hopkinson’s elite social circles.

In the Federal period, European immigrant musicians dominated Philadelphia musical life. Alexander Reinagle (1756-1809), born in England, settled in Philadelphia in 1786 and became a leading musical figure. In addition to composing “serious” works such as piano sonatas, Reinagle wrote and arranged popular songs, marches, and dance pieces. In 1787 he arranged and compiled Select Collection of the Most Favourite Scots Tunes, followed in 1788 by Collection of Favorite Songs. From 1793 to 1803, when Philadelphia was the cultural center of the United States, Reinagle served as musical director for the city’s Chestnut Street Theatre, arguably the premier American entertainment venue of the period.

Reinagle’s contemporary and occasional collaborator, London-born Benjamin Carr (1768-1831), sometimes called the “Father of Philadelphia Music,” settled in the city in 1793 and became prominent as a singer, organist, composer, and successful music publisher. Like Reinagle, Carr composed in a wide range of idioms, including popular music. One of the best-known songwriters of Federal-period America, Carr wrote both musically sophisticated art songs and simpler songs for popular tastes, which he published individually as sheet music, in multi-song collections, or in various music periodicals. Carr’s most popular song was “The Little Sailor Boy” (1798), but he also composed and published song collections setting the words of famous poets and playwrights to music.

The most widely known song to come out of Federal-period Philadelphia was “Hail, Columbia” (1798), a patriotic rallying cry written as the United States was on the verge of war with France. Joseph Hopkinson (1770-1842)—a Philadelphia lawyer, later U.S. congressman and federal judge, and son of Francis Hopkinson—wrote the words, set to the tune of “The President’s March,” a patriotic instrumental piece by Philip Phile (c. 1734–93), a German immigrant musician active in Philadelphia in the 1780s and 1790s. Premiered at the Chestnut Street Theatre on April 25, 1798, “Hail, Columbia” was an instant hit and, following publication by Benjamin Carr, was widely disseminated in sheet music form throughout the nation. It was one of several songs considered America’s unofficial national anthem, until Congress officially designated “The Star-Spangled Banner” in 1931. It has since served as the official song of the United States vice president.

Music Publishers and Popular Musicians

As the nationwide popularity of “Hail, Columbia” demonstrated, Philadelphia-based music publishers made the city the most important center for popular music in early America. Thousands of popular songs issued from the presses of Benjamin Carr’s Musical Repository on High (later Market) Street, Willig’s Musical Magazine on Chestnut Street, and others. George Willig (1764-1851), who immigrated to Philadelphia from Germany in 1794, took over an earlier music publishing business and built it into one of the largest in the nation. In 1843, the firm Lee & Walker, founded a few years earlier by former Willig employees, published “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean,” a patriotic song whose authorship, although in dispute, is generally credited as words by Philadelphia singer and songwriter David T. Shaw and music by Thomas a’Beckett Sr. (1808-90), an English-born actor and musician active in Philadelphia from the late 1830s to 1890. Like “Hail, Columbia” forty-five years earlier, “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean” became very popular and served for a time as one of the nation’s unofficial national anthems.

In 1818 George Willig published A Collection of New Cotillions, a set of dance pieces by African American musician Francis Johnson (1792-1844), a popular bandleader and instrumentalist, prolific composer, and entrepreneurial musician. Johnson was the favored bandleader for the parties and balls of Philadelphia’s social elite, led wind and brass ensembles for the city’s major military companies, and concertized throughout the Philadelphia region and beyond—remarkable achievements for a Black musician of his time. His Collection of New Cotillions was the first music by an African American to be published, and Johnson became the first American, Black or white, to lead a musical ensemble on a tour of Europe in 1837. Local publishers issued some three hundred Johnson compositions, mostly marches and dance pieces but also some ballads and songs. As published, these works were squarely in the European popular tradition, but contemporary accounts indicate that Johnson took considerable rhythmic and melodic liberties in performance.

Minstrelsy

As Johnson was entertaining audiences with his cultivated, European-derived music, a new “low-brow” type of popular music with African American roots was emerging: blackface minstrelsy. Generally considered the first distinctly American form of music, minstrelsy grew out of white performers performing derogatory imitations of African American life and mannerisms. White entertainers “blacked up” their faces with burnt cork and performed exaggerated songs and dances supposedly based on the music, speech patterns, and dance steps of enslaved Black people on southern plantations. By the middle of the nineteenth century, such performances had evolved into the standardized, enormously popular minstrel show. Philadelphia was an important center in the development of minstrelsy, serving as home to well-known minstrel performers, prominent minstrel theaters, and publishing houses that issued minstrel songs, the latter known variously as “Ethiopian” songs, “coon” songs, or other derogatory designations.

Popular minstrel performers Edward Pierce “E. P.” Christy (1815-1862) and Samuel S. Sanford (1821-1905), who were white, and James Bland (1854-1911), who was Black, had important ties to Philadelphia. Bland was one of many African Americans who, faced with few other options as entertainers, became minstrel performers in the late nineteenth century, despite the genre’s degrading portrayals of Blacks. Dubbed the “World’s Greatest Minstrel Man,” Bland lived in Philadelphia briefly when he was young, and he purportedly fell in love with the banjo after hearing a local Black street musician play the instrument. He later spent his final years in the city. His prolific songwriting output included “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers,” the unofficial theme song of the Philadelphia Mummers, and longtime standards “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” and “In the Evening By the Moonlight.”

Songwriters and Venues

Although Philadelphia’s preeminence in music publishing yielded to New York City by the middle of the nineteenth century, local publishing houses turned out numerous patriotic tunes, genteel love songs, sentimental ballads, and march and dance pieces. Sentimental ballads—songs with sad, often maudlin lyrics of mourning the loss of a loved one, longing for home, or cherishing memories of happier times—were especially popular in the nineteenth century. Philadelphia songwriter, publisher, and music store proprietor Septimus Winner (1827–1902) wrote several well-known sentimental songs, one of which, “Listen to the Mocking Bird,” became hugely popular. Winner had heard an African American street musician whistle a melody imitating a mockingbird and fashioned it into a song, which Lee & Walker published in 1855 under Winner’s pen name, “Alice Hawthorne.” Although the melody of “Listen to the Mocking Bird” is rather upbeat, the lyrics—the singer mourns the loss of his beloved, remembering when they would listen together to a mockingbird—are very much in the sentimental ballad tradition. The song sold millions of copies of sheet music and remained a perennial favorite. In 1869, Winner’s brother, songwriter and music publisher Joseph Eastburn Winner (1837-1918), wrote and published “The Little Brown Jug,” which also had a long period of popularity.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, before recordings and radio fundamentally changed how people listened to music, songs reached audiences through live performances or sheet music. Outdoor band concerts became very popular in this period. John Philip Sousa (1854-1932), America’s “March King,” first came to Philadelphia in 1876 to perform in an orchestra as part of the U.S. Centennial festivities. He remained for several years and played in pit orchestras of local theaters, where he learned to conduct. By the early twentieth century, Sousa was the nation’s most popular bandleader and a renowned composer of march tunes. His marches could be heard throughout region, from major amusement parks to small-town gazebo concerts. From 1901 to 1926, Sousa’s outdoor concerts at Willow Grove Park, outside Philadelphia in Montgomery County, were a very popular attraction.

In addition to outdoor concerts, numerous local vaudeville houses, theaters, and opera houses presented variety shows, operettas, and musical comedies that featured popular songs of the day. Philadelphia also served as one of the main tryout cities for Broadway musicals before they headed to New York City, so local audiences had early opportunities to hear songs that later became well-known.

Changing Cultures and Technologies

Recordings and radio revolutionized popular music in the early twentieth century, allowing music to be disseminated much more broadly and rapidly. The Berliner Gramophone Company of Philadelphia began recording popular singers and bands in the mid-1890s, and its successor in the gramophone business, the Victor Talking Machine Company, formed in 1901 and moved its recording studio to its manufacturing complex in Camden, New Jersey, in 1907. The company produced and sold popular recordings that reached the homes of millions. Commercial radio broadcasting, which began in Philadelphia in 1922, became another major outlet for popular music, with many local stations sponsoring in-house bands and vocalists.

Popular music culture in the Philadelphia area also absorbed the influences of waves of immigrants who settled in the region in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, both African Americans from the southern United States and migrants from eastern and southern Europe. Molly Picon (Malka Opiekun, 1898-1992), born to Polish-Jewish immigrants, grew up in Philadelphia Jewish neighborhoods and became immersed in local Yiddish theater. Ethel Waters (1896-1977), born in Chester, Delaware County, and raised partly there and partly in African American neighborhoods of South Philadelphia, grew up surrounded by the vibrant local Black music scene. African American singer/actress Pearl Bailey (1918-90), born in Newport News, Virginia, moved to Philadelphia with her family in the early 1930s and started her professional career after winning an amateur contest at the Pearl Theater on Ridge Avenue in North Philadelphia in 1933. Mario Lanza (Alfredo Arnold Cocozza, 1921-59), who was born in South Philadelphia to Italian immigrants, had early training and experience in the Italian opera tradition. Each went on to become a major singing and acting star across many media—stage, screen, recordings, radio, and, later, television.

Singers Nelson Eddy (1901-67) and Jeanette MacDonald (1903-65) emerged from the Philadelphia entertainment world in the early twentieth century and became forever linked in American popular culture. MacDonald was born and raised in Philadelphia; Eddy moved there with his family as an adolescent. Eddy began in opera and operetta, MacDonald as a dancer-turned-singer. Each went on to great individual success, while their starring roles as romantic partners in 1930s and 1940s Hollywood film musicals endeared them to millions.

Professional songwriters in this period generally gravitated to New York or Hollywood, the nation’s two primary entertainment centers. Philadelphia native Joseph “Joe” Burke (1884-1950), a graduate of the Philadelphia Conservatory of Music, moved between his hometown and the other cities while writing hit songs such as “Tiptoe Through the Tulips” (1929), “Moon Over Miami” (1935), “Getting Some Fun Out of Life” (1937), and “Rambling Rose” (1948).

Rock and Roll

In the years following World War II, Philadelphia produced several singers who succeeded in mainstream popular music geared toward adult audiences, including Katie “Kitty” Kallen (1921-2016), Al Martino (Jasper Cini, 1927-2009), Edwin Jack “Eddie” Fisher (1928-2010), and the Four Aces, led by Al Alberts (Al Albertini, 1922–2009). This market was overtaken in the mid-1950s by rock ‘n roll, a high-energy, youth-oriented music that emerged from African American rhythm and blues and went on to dominate popular music for decades.

With its large Black population and long tradition of African American popular and religious music, Philadelphia became a hotbed of rhythm and blues, which grew out of jazz, blues, and gospel music. Local rhythm and blues groups, known as “jump bands,” included Jimmy Preston (1913–84) and His Prestonians, Chris Powell (1921–70) and His Blue Flames, and various groups led by Doc Bagby (c.1919-70). They played Black dance halls and clubs and had hit records on the rhythm and blues charts, the popular music charts that tracked Black music sales. White musicians began incorporating elements of rhythm and blues into their music, including country and western bandleader William John Clifton “Bill” Haley (1925–81), based in Boothwyn, Delaware County. His group, Bill Haley and His Comets, had hit records in the early 1950s with their blended country and western/rhythm and blues style and then massive success in 1955 with “Rock Around the Clock,” the first mega-hit in the new rock and roll style, which sold millions of records worldwide and helped usher in the rock and roll era.

Local Music, National Stage

As rock and roll swept the nation in the mid-1950s, several independent record labels and the incredibly influential teen music and dance television show “American Bandstand” made Philadelphia a key center in the popular music industry. “Bandstand,” broadcast nationally from Philadelphia from 1957 to 1964, featured teenagers dancing to the latest records and live appearances by popular recording artists. It began as a local radio show in the late 1940s, debuted as a local TV program in October 1952, and went national in August 1957, with the charismatic Richard Wagstaff “Dick” Clark (1929-2012) as host. Watched by millions of teenagers nationwide every weekday afternoon, the show was a major trendsetter in popular music.

Philadelphia-based independent record labels such as Cameo-Parkway and Chancellor became hit-making machines in the late 1950s and early 1960s, featuring primarily homegrown artists who specialized in teen dance tunes and romantic ballads. The label owners had close ties to, and in some cases business relationships with, Dick Clark, and their recording artists appeared often on Bandstand, which boosted their record sales significantly. Cameo-Parkway had singer/guitarist Charlie Gracie (Charlie Graci, 1936-2022), singers Bobby Rydell (Robert Ridarelli, 1942-2022), Dee Dee Sharp (Dione LaRue, b. 1945), and Chubby Checker (Ernest Evans, b. 1941), and vocal groups the Orlons and the Tymes. Chancellor had singers Frankie Avalon (Francis Avallone, b. 1940) and Fabian (Fabiano Forte, b. 1943). Checker’s “The Twist,” a 1960 cover of a rhythm and blues dance tune, was a huge hit—the only non-holiday song in history to go to number one twice, in 1960 and again in 1962—and started an enduring dance craze.

During this period, young people singing small-group harmonies on street corners and in school hallways created doo wop, a vocal style of rhythm and blues with primarily African American origins. In Philadelphia, African American artists the Silhouettes made “Get a Job” a number one hit in 1958, and Lee Andrews (Arthur Lee Andrew Thompson, 1936–2016) and the Hearts had big hits in 1957 and 1958 with “Teardrops,” “Long Lonely Nights,” and “Try the Impossible.” White groups also achieved popularity in doo wop, including Danny & the Juniors, who had a number-one hit with “At the Hop” and a top twenty hit with “Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay, both in 1958; and the Dovells with “The Bristol Stomp” (inspired by a dance teenagers were doing in nearby Bristol, Bucks County), which reached number two in 1961.

Philly Soul

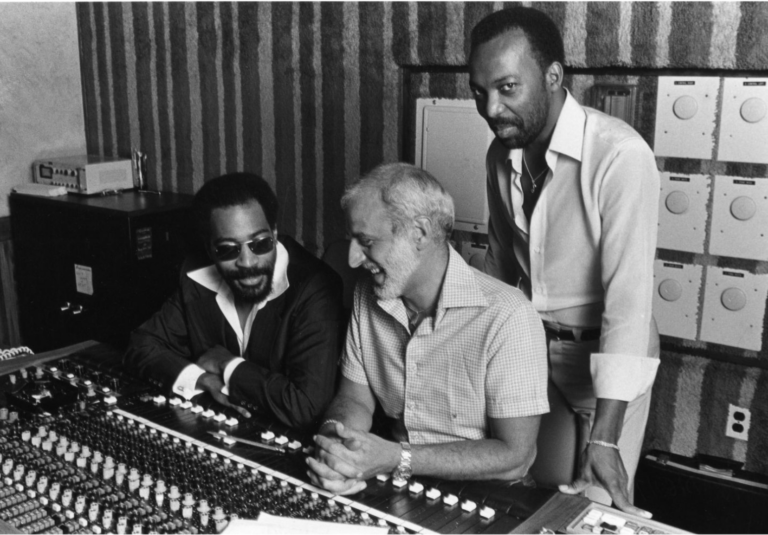

Philadelphia lost its preeminent role in popular music in the mid-1960s as tastes changed and “American Bandstand” relocated to Los Angeles, but a new local style, dubbed “Philly Soul,” returned the city to international prominence in the early 1970s. A Black style emerging from rhythm and blues and popular music but with a strong gospel influence, soul music began to gain popularity nationally in the early 1960s. “Yes, I’m Ready” by local singer Barbara Mason (b. 1947), became the first big hit in the Philly Soul style in 1965. Three key figures emerged as the chief architects of the style: songwriter/producers Kenneth “Kenny” Gamble (b. 1943), Leon Huff (b. 1943), and Thomas “Thom” Bell (1943-2022). Gamble was born in Philadelphia, Huff in Camden, New Jersey, and Bell in Kingston, Jamaica, but raised in Philadelphia. Thom Bell scored a number of hits in the late 1960s and early 1970s with Philadelphia vocal groups the Delfonics and Stylistics, and with the Spinners, who were from Detroit but recorded in Philadelphia under Bell.

Gamble and Huff, after succeeding as a producer/songwriting team for other labels—their first big hit together was “Expressway to Your Heart” by the Soul Survivors in 1967—formed Philadelphia International Records, billed as the “Sound of Philadelphia,” in 1971. Black-owned and managed and featuring primarily African American artists, Philadelphia International released dozens of gold and platinum records from the early 1970s to early 1980s. Its roster included local singers and groups that had come up in the city’s rich Black music scene—the Intruders, Harold Melvin (1939-97) and the Blue Notes, Theodore “Teddy” Pendergrass (1950-2010), Billy Paul (Paul Williams, 1934-2016), Patti LaBelle (Patricia Holte, b. 1944), and the Blue Bells, and others—as well as out-of-town artists who came to Philadelphia to capture the city’s distinctive soul sound, including Lou Rawls (1933-2006), the Jackson Five, and the O’Jays, one of Philadelphia International’s most popular groups. After over a decade of major success, Philadelphia International Records began to decline in the early 1980s, as the Philly Soul style fell out of favor, replaced by new forms of Black popular music, such as rap and new styles of funk.

Philadelphia continued to produce popular white rock and roll artists, including Todd Rundgren (b. 1948), who came into prominence in the late 1960s; Hall & Oates (Daryl Hohl, b. 1946, and John Oates, b. 1948), who had the first of their many hits in the late 1970s; and the Hooters, who became popular in the mid-1980s. By then, rock had become big business, and Philadelphia was a major stop on the rock touring circuit. Electric Factory Concerts, founded in the late 1960s by local club owners the Spivack brothers and managed by promoter Larry Magid (b. 1942), became one of the premier rock concert promotion companies in the nation.

Neo Soul and Rap

Philadelphia again became an important center of Black popular music around the turn of the twenty-first century with the emergence of “Neo Soul,” an African American style built on the legacy of soul but incorporating modern musical elements. Philadelphia-based Neo Soul artists include vocal group Boyz II Men and singers Jill Scott (b. 1972), Musiq Soulchild (Taalib Hassan Johnson, b. 1977), Bilal (Bilal Sayeed Oliver, b. 1979), and Jazmine Sullivan (b. 1987).

Philadelphia was also important in the development of rap. In 1985, Schooly D (Jesse Bonds Weaver Jr., b. 1962) released “P.S.K. (What Does It Mean?),” generally considered the first gangsta rap song. (The title references the Parkside Killers, a gang from Philadelphia’s Parkside neighborhood.) Other local rappers that were popular in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century include the duo DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince (Jeffrey Allen Townes, b. 1965, and Willard Carroll “Will” Smith II, b. 1968), Beanie Siegel (Dwight Equan Grant, b. 1974), and Meek Mill (Robert Rihmeek Williams, b. 1987).

The most popular and influential Philadelphia African American group of the early twenty-first century was the Roots, led by drummer/producer Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson (b. 1971, the son of Lee Andrews), and vocalist/rapper Black Thought (Tarik Luqmaan Trotter, b. 1971), both graduates of Philadelphia High School for the Performing Arts. In addition to success with albums, concerts, and festivals, The Roots gained broad national exposure as house band for the TV show Late Night with Jimmy Fallon and subsequently The Tonight Show, where they were routinely introduced as “The Roots from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.”

By the early twenty-first century Philadelphia could boast over 250 years as an important center for popular music. From mainstream popular song to breakthrough new styles, the city has produced a wide range of popular music and nurtured many influential artists.

Jack McCarthy is an archivist and historian who specializes in three areas of Philadelphia history: music, industry, and Northeast Philadelphia. He regularly writes, lectures, gives tours, curates exhibits, and directs projects focusing on these topics. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2023, Rutgers University.