Wilmington, Delaware

By Stephen Nepa | County Seat

Essay

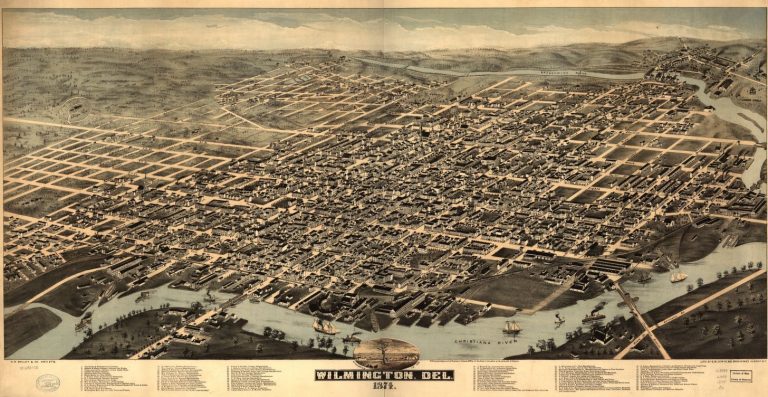

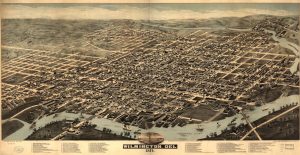

Located thirty miles southwest of Philadelphia, Wilmington is Delaware’s largest city and the New Castle County seat. It originated as a colonial trading area and ferry crossing and later became one of the country’s most vital industrial and chemical-producing centers. With the decline of manufacturing near the close of the twentieth century, the city emerged as America’s “corporate capital.” Despite the city’s industrial might and corporate wealth, its history also reflected the spatial, economic, and racial disparities seen in cities across Greater Philadelphia and the nation. Often overshadowed by the region’s larger cities, Wilmington remained modest in size yet ambitious in scope.

Prior to Swedish and Dutch colonization in the early 1600s, the area that became Wilmington contained a vast population of Lenni Lenape Indians scattered in villages along the Delaware River. Over time, the Indians and settlers engaged in trade, exchanging furs for European-made goods. New Castle, six miles to the south, initially served as the area’s primary trading center. But in 1638, Swedish colonists erected Fort Christina on a narrow stretch of land between the Brandywine and Christina Rivers, the latter of which fed into the larger Delaware. In 1669, Governor Francis Lovelace (1621-75) chartered the Christina’s first ferry service north of present-day Newport. Twenty years later, an additional crossing opened over the Brandywine, generating commerce on the peninsula between the rivers. In 1731, with the colony then under English rule, the humble settlement gained incorporation.

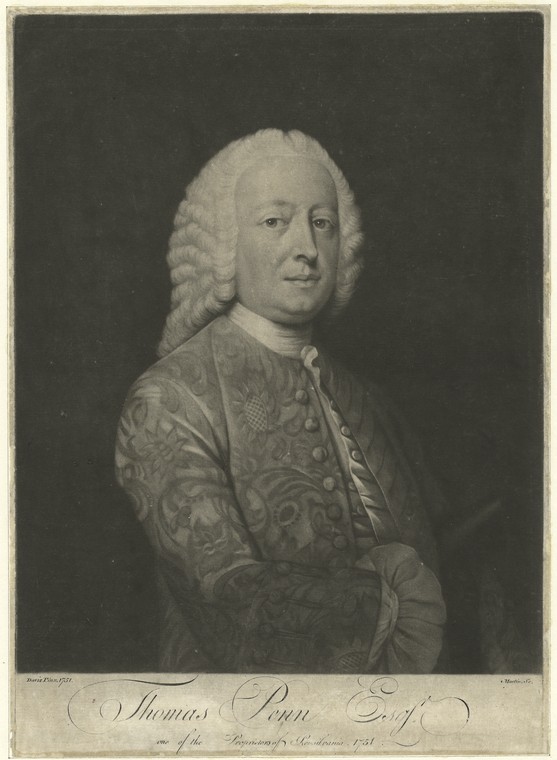

Thomas Penn (1702-75), son of Pennsylvania founder William Penn (1644-1718), served as the first proprietor of the Borough of Wilmington, which he named for Spencer Compton (1673-1743), the First Earl of Wilmington and close associate of King George II (1683-1760). With easy river access to the interior and the Atlantic Ocean, Wilmington attracted craftsmen, merchants, millers, and artisans, who transformed the fledgling borough into a key producer of flour and grain; the city’s so-called “Brandywine Superfine” flour reached markets throughout the colonies and ports as far away as Europe and the West Indies. In 1771, after concluding a carpentry apprenticeship, Samuel Canby (1751-1832) established the borough’s first textile mill along the Brandywine near Orange Street. Later, his son James Canby (1781-1858) assumed control of the mills and eventually helped found the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad, serving as its first chief executive. Although Wilmington witnessed no significant combat during the American Revolution, the borough provided shelter for American troops during the 1777-78 British occupation of nearby Philadelphia. Regiments from Maryland and Delaware remained in Wilmington to protect patriot supply lines along the Elk and Delaware Rivers.

Brandywine Village

Industrialization expanded in the Wilmington area during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Brandywine Village, a flour milling center, opened in 1753. Founded by prominent Quakers William Shipley (1693-1768), his wife Elizabeth Levis-Shipley (1690-1777), and their partner Thomas Canby Jr. (1702-1764), the complex contained twelve mills and more than sixty homes. In 1783, engineer Oliver Evans (1755-1819) introduced his automatic flour mill to the complex, a system that later revolutionized the industry. Working from his Newport, Delaware, and Philadelphia shops, Evans also experimented with steam and refrigeration technologies. With industry came growth; by the early 1800s, Wilmington’s population reached five thousand residents and its papermaking, grain, and flour processing operations were complemented by new technologies and industries. In 1802, French chemist E.I. du Pont (1771-1834) established a gunpowder mill along the Brandywine upstream from the city. Over the next century, his namesake company remained headquartered in Wilmington and grew into the world’s largest explosives manufacturer. Other prominent local families during the period included the Talleys, active in the timber business; the Bringhursts, who prospered in shipping and banking; and the Bancrofts, whose patriarch Joseph Bancroft (1803-1874) opened a textile mill along the Brandywine in 1831.

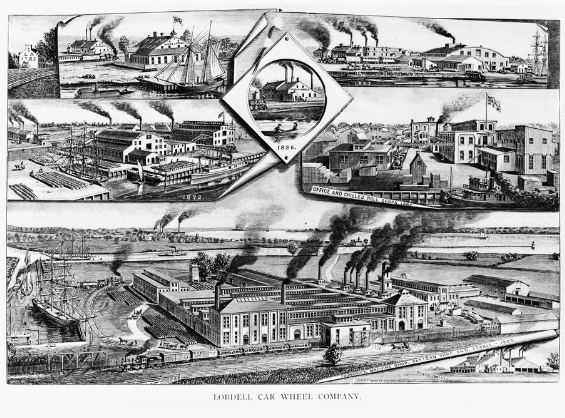

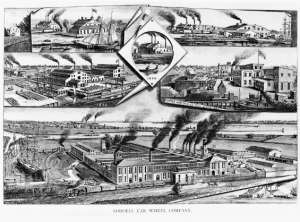

The Delaware legislature rechartered the borough as the city of Wilmington in 1832, and with the completion of the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad five years later, the city’s riverfront advantages merged with the Northeast’s burgeoning rail network. Shipbuilding, carriage making, and iron founding flourished during the 1840s, generating demand for raw materials and skilled workers. Yet railroad cars and their related components generated much of the city’s nineteenth-century economic activity. Prior to the Civil War, companies including Harlan and Hollingsworth, Pusey and Jones, and Jackson and Sharp opened factories along the Christina, placing Wilmington at the forefront of U.S railcar production. The Lobdell Car Wheel Company led the nation in train wheel production while Jackson and Sharp exported cars and later electric trolleys to Europe, Latin America, and Asia. As Wilmington’s industrial base increased, so too did its population of foreign workers, many of whom arrived from Ireland and Germany during the 1840s and 1850s.

The population of New Castle County had included numerous enslaved Africans, primarily in its rural southern areas, since the 1700s, but by the early 1800s members of Wilmington’s free Black community achieved considerable home and property ownership and established a number of schools and churches. In 1827, the Wilmington Union Colonization Society petitioned the state assembly for a resolution to manumit slaves, provided they return to Africa, a measure deeply at odds with the city’s free Blacks, who argued colonization ran counter to the nation’s founding principles. Wilmington also harbored considerable abolitionist sentiment and with its location less than ten miles from the Pennsylvania border served as the northeastern terminus for the Underground Railroad. Hardware purveyor Thomas Garrett (1789-1871) assisted Harriet Tubman (?-1913) on eight of her missions. Garrett’s covert activities eventually landed him in federal court, where in 1848, he was fined $5,400 for violating the Fugitive Slave Act. Other notable Wilmington abolitionists included shoemaker Abraham Doras Shadd (1801-82) and his daughter Mary Ann Shadd (1823-93), who used their homes to aid escaped slaves, as well as Samuel Burris (1808-68), who coordinated escape routes north into Philadelphia and out of Kent and Sussex Counties to the south. Although a slave state in 1860, with its citizens polarized by Northern and Southern sympathies, Delaware remained in the Union following the outbreak of the Civil War. During the conflict, Wilmington’s industries provided the Union Army with much-needed clothing, blankets, riverboats, rail cars, and artillery.

A Key Industrial Contributor

Despite competition from larger cities in the Northeast and Midwest, Wilmington’s productive capacity and population rose after 1865, making the city a key element in greater Philadelphia’s industrial network. Its yards and factories churned out carriages and rail cars, and by 1870, produced more iron ships than the rest of the nation’s facilities combined, earning the city the nickname “the American Clyde.” With such activity, the city’s population, which stood at 21,258 people at the onset of the Civil War, grew steadily, reaching nearly 77,000 by 1900. Newly arrived immigrants from Italy, Hungary, and Poland settled in neighborhoods on the edges of downtown or in low-lying, flood-prone areas along the Christina. Most lived in two- or three-story brick row houses, similar to those in Philadelphia and Camden, and found work in textiles or constructing the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad. However, fierce competition for jobs prompted the Wilmington City Council in the 1880s to temporarily prohibit Italian or Hungarian immigrants from employment on public works projects.

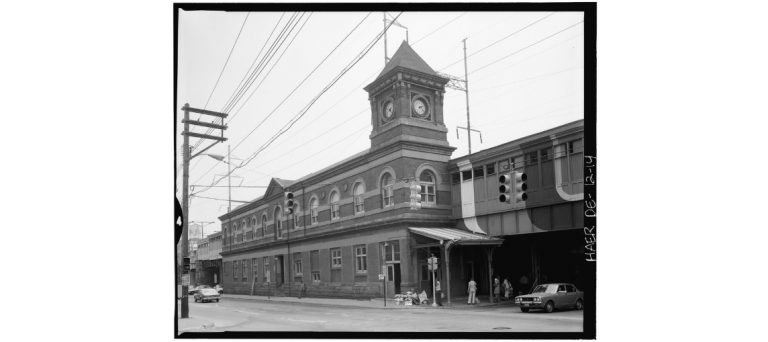

In the late nineteenth century, Wilmington confronted side effects from decades of industrial activity. The Brandywine River, the city’s main source of municipal water, became heavily polluted. Outbreaks of cholera and typhoid fever occurred regularly in the 1870s and 1880s, prompting city officials to build reservoirs, a modern sewer system in 1890, and in 1909, Wilmington’s first water purification plant. In recognizing the ills of the industrial city, Wilmington’s elite removed to the suburbs, constructing mansions in areas such as Kentmere, Westover Hills, and Montchanin. Yet many prominent citizens such as U.S. Sen. Thomas F. Bayard (1828-98), William Poole Bancroft (1835-1928), Pierre S. du Pont (1870-1954), businessman John Jacob Raskob (1879-1950), and U.S. Sen. T. Coleman du Pont (1863-1930) donated influence, land, funding, or ingenuity to beautify Wilmington’s public spaces and improve its infrastructure. Bancroft, known as the godfather of Wilmington’s park system, at Bayard’s urging in 1889 bequeathed to the city acreage for both Rockford Park and Brandywine River Park; the former’s observation tower, built in 1901, became one of Wilmington’s most beloved landmarks. Pierre S. du Pont personally financed road improvements of Kennett Pike (State Route 52), and enlisted Raskob to redesign Rodney Square, the city’s main public square. In 1905, the Pennsylvania Railroad elevated its street-level tracks through Wilmington and retained architect Frank Furness (1839-1912) to design a new station.

The Du Pont family also left an indelible architectural legacy in the city, opening the twelve-story Du Pont Building on Rodney Square in 1906 and the luxurious Hotel Du Pont in 1913. The hotel and its restaurant, the Green Room, remain two of Wilmington’s finest establishments. In 1924 the Du Pont Highway (US 13), personally financed by Pierre Du Pont, opened to vehicular traffic, allowing easier travel between the city and Delaware’s southern counties. Following the death of Wilmington-based artist Howard Pyle (1853-1911), friends, patrons, and former students honored his legacy by establishing the Wilmington Society for Fine Arts. The society later received the art collection of William’s brother Samuel Bancroft Jr. (1840-1915), who also donated eleven acres in Kentmere for the site of the Delaware Art Museum, which opened to the public in 1938. Decades later, artist Helen Farr Sloan (1911-2005) donated to the museum hundreds of paintings and prints executed by her husband John French Sloan (1871-1951), a member of the Philadelphia-founded Ashcan School; over time, her contributions amounted to the largest collection of his works held by a museum.

A Boost From World War I

In the 1910s, Pierre S. du Pont foresaw conflict in Europe, and in 1915 his company began supplying the Allies with armaments. By World War I’s conclusion, Du Pont had provided 40 percent of Allied explosives and seen its labor force increase dramatically, from 5,300 in 1914 to 48,000 four years later. The company’s regional footprint grew as well, as its facility in Carney’s Point, New Jersey, expanded and handled the bulk of wartime production. Hundreds of soldiers from Wilmington fought in the Battle of Argonne while thousands more at home participated in roadbuilding and maintenance work. The city’s shipyards supplied hundreds of submarine-chaser yachts and patrol craft. After the war, Du Pont reduced its munitions production and, aided by confiscated German research and patents, greatly expanded its production of chemicals, dyes, and cinematic film. Over time, this growth led Wilmingtonians to call Du Pont simply “the company.” Aiding the city’s postwar boom, in 1920 the Lobdell Car Wheel Company sold 101 acres of land to the city for the construction of modern port facilities. Two years later, the Port of Wilmington opened for commerce, exporting lumber, cork, burlap, lead, iron ore, fertilizer, and petroleum. As the 1920s drew to a close, Wilmington’s 110,000 residents enjoyed the prosperity seen elsewhere around the country, evident in its movie theaters, clothing stores, hotels and restaurants, sporting venues, and growing use of automobiles.

During the Great Depression, Wilmington benefited from several New Deal projects overseen by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civil Works Administration (CWA). These included new public schools; road, sidewalk, and bridge improvements; upgraded dikes along the Christina River; and new buildings for the Wilmington Waterworks and the United States Postal Service. Located on Rodney Square, the Classical Revival-style post office opened in 1937 and contained murals designed by Albert Pels (1910-98) and Herman Zimmerman. As the nation plunged into World War II, Wilmington’s citizens and industries rushed to meet Allied demands. Thousands enlisted for military service. The New Castle County Airport shifted solely to military use. Iron founding, textile, and shipbuilding activity all increased dramatically as did the chemical and munitions output of the Du Pont, Hercules, and Atlas companies. Additionally, Du Pont engineers, working in Wilmington; Oak Ridge, Tennessee; and Hanford, Washington, played key roles in the Manhattan Project, the secret program to develop the atomic bomb.

Wilmington prospered after World War II. Du Pont increased its workforce by ten thousand in the early 1950s and over the next three decades pioneered advances in plastics, nylon, rayon, Kevlar, Tyvek, and several other chemicals and products that helped fuel the nation’s postwar consumption; the company even advertised its famous “nylon suites” at the Hotel du Pont. With thousands of new jobs in the area, housing developments appeared in suburbs such as Sherwood Park, Pike Creek, Duncan Woods, Talleyville, and Forest Hills Park. While railcar production declined sharply, automobile production emerged as the state’s largest industry, second only to Du Pont. Shifting to peacetime operations, General Motors opened its Wilmington plant in 1947 on Boxwood Road while Chrysler opened a plant in Newark in 1952. In 1957, construction commenced on Interstate 95, which passed directly through downtown Wilmington between Jackson and Adams Streets. The highway, which many neighborhood residents opposed, was completed in 1968 and over time, ferried commuters away from downtown businesses. To relieve traffic congestion, the Interstate 495 bypass, along the city’s eastern edge, opened in 1977. With suburbanization came new recreational opportunities such as the Concord Mall (1965), the Delcastle Sports Complex (1970), and the Christiana Mall (1978).

Rioting of 1968

Despite Wilmington’s prosperity, race relations remained fraught in the postwar decades. While local institutions such as Salesianum High School, the YMCA, and the Hotel Du Pont began integrating in the early 1950s, the fight to desegregate the city’s public schools did not end until the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. Wilmington’s schools complied with the decision later that year. In July 1967, civil disturbances in the city’s Black neighborhoods prompted Mayor John E. Babiarz (1915-2004) to establish an evening curfew and temporary bans on liquor sales. Following the April 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-68), three thousand National Guard troops arrived to quell ten days of widespread rioting and looting of downtown stores. Though Babiarz requested the troops be withdrawn after twenty-four days, Governor Charles L. Terry, Jr. (1900-70), a southern-style Democrat who won office on a platform of law and order, refused on the grounds of maintaining security and protecting property. The troops remained for nine months, leading to Terry’s reelection loss in November and marking the longest military occupation of an American city since the Civil War.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, many of Wilmington’s industrial interests contracted or relocated out of state. Its population dwindled. But the city entered a new phase. Du Pont, Hercules, and BASF continued to grow. Hercules, which spun off from Du Pont decades earlier, completed a 680,000-square-foot headquarters at the edge of the Midtown-Brandywine neighborhood—the state’s largest office building erected during the 1980s. Although Du Pont continued as the city’s largest employer, in September 2017 the storied company completed a $130 billion merger with Dow Chemical; by mid-2019, the newly formed conglomerate planned to break into three independent, publicly traded units. Beyond chemicals, Wilmington continued to diversify. In 1981, with the passage of the Financial Center Development Act, the state’s banking and tax laws were liberalized to attract outside investment. Banking giants such as Chase Manhattan, Bank of America, ING, MBNA, and Barclays opened offices as did pharmaceutical and telecommunications companies. By the 1990s, the city gained a somewhat dubious reputation as a base for “shell companies” suspected of avoiding government regulations and laundering foreign sources of income. These developments earned Wilmington yet another nickname, “corporate capital.”

Even with the influx of corporate investment, Wilmington faced other challenges in the 1990s and early 2000s, such as the environmental cleanup of dozens of industrial sites, the disappearance of automobile manufacturing, and persistent inequality between the city and its suburbs. Decades of manufacturing led to a high concentration of Superfund and brownfield locations, with New Castle County alone containing more than several U.S. states. Many of the most contaminated, such as the Tybout’s Corner landfill, saw remediation completed by the early 2000s. One of the most successful brownfield projects, Justison Landing, was completed in 2005; once home to tanneries and shipyards, the thirty-three-acre site transformed into apartments, offices, restaurants, and a stadium for the Wilmington Blue Rocks, a minor league baseball affiliate of the Kansas City Royals. In 2009, the last active car factory in the eastern U.S, Wilmington’s Boxwood Road GM plant, closed. As of 2019, with the plant demolished, plans included a new e-commerce facility on the site.

Demographic Shifts

Demographics in Wilmington shifted after 1990. The proportion of white residents fell from 40 to 28 percent by 2010, a period of steady gains in the African American population (which reached 58 percent) and Latino residents (12 percent). After the 2010 census, projections estimated Wilmington’s population growing by 0.4 per cent, far below the gains of Philadelphia. Although surrounded by affluent areas on its northern and western edges, in 2018 Wilmington had one of the nation’s highest murder rates and nearly half of its residents under age eighteen lived below the federal poverty line.

Throughout its nearly 350-year existence, Wilmington has mirrored the aspirations, tensions, and historical changes of the United States as a whole. Although never achieving the prominence of nearby Philadelphia or Baltimore to its south, the city at times exerted enormous influence for one of its comparatively smaller size. And despite the many challenges that Wilmington faced in the early twenty-first century, it still strived to be, as welcome signs at the city limits proclaimed, “a place to be somebody.”

Stephen Nepa teaches history at Temple University, Pennsylvania State University-Abington, Rowan University, and Moore College of Art and Design. He is a contributing author to numerous books and journals, and regularly appears in the Emmy Award-winning documentary series Philadelphia: The Great Experiment. He received his B.A and M.A. from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and his Ph.D. from Temple. A native of Wilmington, he lives in Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- A History of the Original Settlements on the Delaware (Archive.org)

- Shipbuilding history along the Wilmington riverfront (Delaware Public Media)

- City History (City of Wilmington, Delaware)

- Delaware's Industrial Brandywine (Hagley Library)

- DuPont Company on the Brandywine (Hagley Library)

- Friends of Wilmington's Parks