Orphanages and Orphans

Essay

Philadelphia’s earliest orphanages grew out of social projects intended to help impoverished families. As early the first decades of the eighteenth century, city officials created organizations such as the Overseers of the Poor (later the Guardians of the Poor) to provide relief to those, such as the elderly, widows with children, and orphans, who faced poverty through no fault of their own. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, private groups established orphanages to care for children whose parents could not support them because of poverty or death. By the late twentieth century, group homes and foster care largely replaced orphanages as the primary means of caring for such children.

Prior to the rise of orphanages, orphans often roamed the streets, worked as apprentices through indenture, or faced confinement to almshouses, jails, or insane asylums (State Hospitals). Although many children were orphaned because both parents had died, in other cases orphans still had one or both parents, but due to poverty, illness, widowhood, or other hardship, their parents were unable or unwilling to care for them. Institutions sometimes took in children on the guarantee that a parent would contribute financially to care for their child. Some orphans were indentured out by their extended family, institutions also indentured orphan children. In exchange for labor, these arrangements provided “bound” orphans with gender-specific training, such as agriculture and trades for boys and housewifery for girls. Though rather harsh in nature, these indenture agreements persisted into the early twentieth century.

At the end of the eighteenth century, both war and disease contributed to child homelessness. Local Catholic and Jewish women responded by becoming involved in charitable work. The Sisters of St. Joseph founded St. Joseph’s Orphan Asylum (1797–1984) at Seventh and Spruce Streets following Philadelphia’s deadly yellow fever epidemic of 1793. In 1801, Rebecca Gratz (1781–1869), along with a cohort of women volunteers, established the nonsectarian Female Association for the Relief of Women and Children in Reduced Circumstances to address the needs of “honest and industrious” families left destitute through no fault of their own; it operated a soup kitchen as well as a home for widows and orphans. Orphanages were largely directed by women, a trend that persisted until the late nineteenth century, when social work became more professionalized.

Orphan Society of Philadelphia

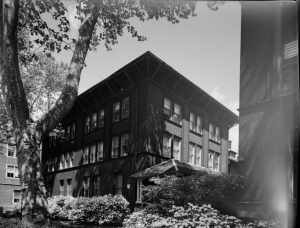

In spite of such efforts, abandoned children were a serious social problem by the early nineteenth century. Disease, immigration, and growing urbanization continued to put a strain on the city’s limited resources. In 1814, a group of Philadelphia women, including Sarah Ralston (1766–1820), Julia Rush (1759–1848), and Rebecca Gratz, founded the Orphan Society of Philadelphia (1814–1965), the region’s first nonsectarian (though Presbyterian-influenced) orphanage, to provide the city’s poor, white, fatherless children of married parents the support and moral education that would eventually render them valuable members of society. Philadelphia was one of the few cities in the United States prior to 1855 that also established orphanages for what were categorized as “special classes” of children. Since white orphanages barred Black children, they were housed with adults at local almshouses. To address this concern, Quaker women established the Association for the Care of Colored Orphans, also known simply as “The Shelter,” in 1822, at Forty-Fourth Street and Haverford Road. The Shelter cared for both boys and girls and offered a homelike environment. New Jersey chartered the West Jersey Orphanage in 1874 to care for “destitute colored children,” which was led by Quakers John Cooper (1814–1894) and his wife, Mary. Located at Oak and Chestnut Streets in Camden, it remained operational until the 1920s, at which point the children were moved to the Camden Home for Friendless Children (1865–1979) at the corner of Fifth and Plum (later Arch) Streets.

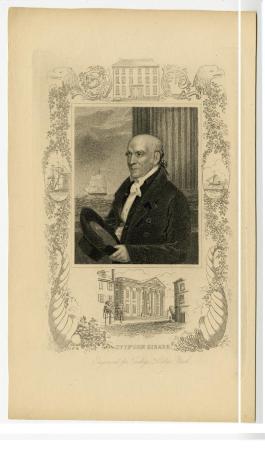

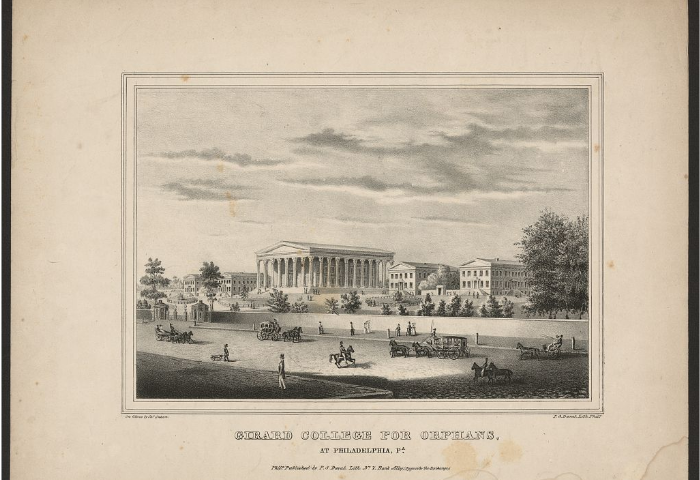

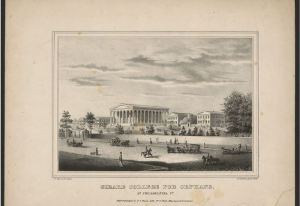

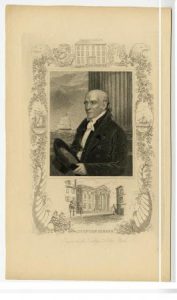

By the mid-nineteenth century, reformers viewed orphanages as a progressive alternative to housing children with adults in almshouses, where, they feared, they would be exposed to criminals and social deviants. Girard College, opened in 1848 for “poor white male orphans,” embraced the model of providing young boys instruction in the trades and mechanical training. The school was founded at the direction of Stephen Girard (1750–1831), who left a $2 million endowment in his will to establish the school, situated north of Poplar Street and Ridge Avenue, a location that Girard believed would provide solace from city life and allow boys to escape poverty by obtaining an education that would otherwise have been unavailable to them. Eventually, Pennsylvania (1883) and New Jersey (1899) passed legislation prohibiting the institutionalization of children in asylums designated for adults. Such views led to the creation of several privately funded orphanages, most of which highlighted the need for education, moral reform, and skills training.

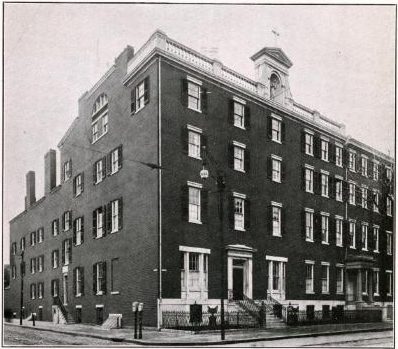

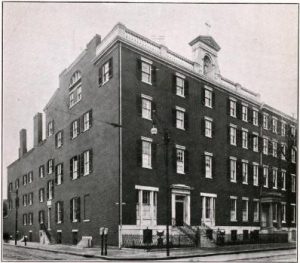

Faith-based groups also founded orphanages in the mid-nineteenth century. Rebecca Gratz, who served for forty years as secretary of the Orphan Society of Philadelphia, established one of the nation’s first orphanages specifically for Jewish children. Gratz created the Hebrew Sunday School program in 1838. By the end of the nineteenth century, this program opened branches across Philadelphia and served over four thousand students. Out of fear that orphaned Jewish children would be reared in non-Jewish asylums and be estranged from the Jewish community, she founded the Jewish Foster Home Society (later the Jewish Foster Home and Orphan Asylum of Philadelphia), located at North Eleventh and Brown Streets, in 1855. Catholics also operated institutions to provide care for abandoned children. The Sisters of Notre Dame ran St. Vincent’s Orphan Asylum of Tacony, also established in 1855, to serve girls identified as dependent or delinquent.

By the late nineteenth century, orphanages adopted a rehabilitative model, in keeping with beliefs that philanthropy and charity ran counter to progressive ideals of self-sufficiency and self-reliance. New institutions, commonly referred to as industrial schools, emphasized practical skills. Industrial schools did not aim to elevate the social standing of orphans, but rather, to prepare them for a life of genteel poverty. The Foulke and Long Institute for Orphan Girls, originally established at Twelfth and Arch Streets in Philadelphia in 1882 and funded by the endowment of Eleanor Parker Foulke Long (1792–1882) and her husband, Burgess B. Long (1796–1873), served daughters of soldiers from the Civil War, as well as daughters of firemen and other public servants who had “sacrificed for the public benefit,” in accordance with instructions Long had left for the disposition of her estate. Pennsylvania’s first industrial school for girls, the institute provided residence in a Christian setting as well as a traditional education coupled with training in the industrial, social, and cultural arts. In 1888, it merged with the Industrial Home for the Training of Girls in the Arts of Housewifery and Sewing. Other privately funded and run facilities provided practical education for orphaned and abandoned boys, such as St. Francis de Sales Industrial School (1888), in Eddington, Pennsylvania; St. Joseph’s House for Homeless Industrious Boys (1888), in North Philadelphia; St. Joseph’s Industrial School (1896), in Clayton, Delaware; and the Delaware Orphans’ Home and Industrial School (1899), in Wilmington.

In 1909, the White House Conference on Children embraced the notion that home life was the “highest and finest product of civilization” and that, if possible, children should be placed in foster homes rather than institutions or indentured arrangements. In the early 1900s, social agencies began to pay and supervise foster parents. Home inspections became mandatory, and increasing professionalization in the field of social work called for inspectors to maintain records and evaluate the living situations of individual children. While encouraging reunification of children with their families whenever possible, the foster care system paved the way for additional related child welfare reforms, such as adoption, nutrition and vocational training, and child labor laws.

Orphanage Restructuring

Findings presented at the 1909 conference also led to significant restructuring of orphanages. Organizations that previously functioned independently joined under a single umbrella. For example, the Catholic Children’s Bureau, created in 1919, attempted to centralize child welfare efforts. In addition, the increasing professionalization of the social work coupled with increased regulation of childcare institutions and support of the foster care system contributed to the decline of the orphanage.

Such reforms would eventually lead to more comprehensive reforms to protect children from abuse or neglect in the latter half of the twentieth century. In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, the numbers of children needing assistance continued to rise as the prevalence of orphanages declined with the advent of new social programs. The Social Security Act of 1935 represented one federal government attempt to provide financial assistance to families in need. By the end of the Second World War, most orphanages had closed or were replaced by smaller institutions that tried to promote group home environments. Federal legislation concerning child abuse in the 1970s drew national attention to the need for child protection. The Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act of 1980 was created to serve children in their own homes, prevent external placement, and facilitate the reunification of families.

Despite such reform, the late 1980s and 1990s experienced increases in child neglect and foster placements. Cuts in public funding led to a decrease in child welfare resources. Church-based organizations such as Catholic Social Services (previously the Catholic Children’s Bureau) stepped in and expanded outreach beyond foster care and adoption to include programs for immigrants, the elderly and medically fragile, and those in need of transitional housing. Catholic Social Services became one of the largest nonprofit providers of social services in Southeastern Pennsylvania, with centers such as Casa del Carmen (originally located at Seventh and Jefferson Streets), created in 1954, which supported the transitional needs of Puerto Rican immigrants. Institutes such as the Foulke and Long Institute and the Carson Valley School broadened their scope. The Foulke and Long Institute merged in 1960 with the Youth Study Center of Philadelphia, an organization that began in 1909 as the House of Detention. Its primary role was to provide education and medical care to abused and neglected children, as well as to those who had been accused of minor delinquency infractions. The Carson Valley School merged with the Children’s Aid Society in 2008 and shifted to serving families in need of drug and alcohol outpatient services and crisis counseling.

By the twenty-first century, community group homes for families in need of transitional housing, family preservation programs, and services such as those offered by the Department of Human Services, delivered in client homes, had largely replace orphanages. Charitable organizations that had formerly provided care for orphans had broadened their agendas to provide services to those suffering from mental illness and homelessness, as well as to those in recovery from drug and alcohol addiction.

Holly Caldwell received her Ph.D. in history from the University of Delaware, where she wrote her dissertation on the medicalization of deafness and deaf education reform at Mexico’s Escuela Nacional de Sordomudos (National School for Deaf-Mutes). She is an adjunct assistant professor of history at Chestnut Hill College and has also taught at Susquehanna University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- La Salle University Threatens Germantown Landmarks (Hidden City)

- With New Center Coming, Remembering The Southern Home For Destitute Children (Hidden City)

- "The Childrens" Home of York, c. 1865 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Soldier's Orphan School Museum Attraction Details (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Girard College Civil Rights Landmark (ExplorePAHistory.com)