World War II

By Herbert Ershkowitz | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

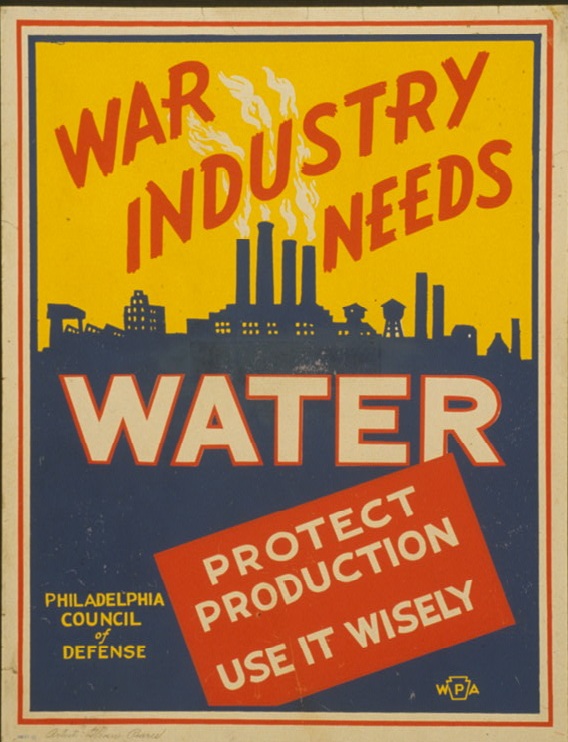

World War II, which created change for industries, populations, and politics in many urban areas in the United States, had a transforming effect on the Philadelphia region. Already industrialized, the region gained new impetus from government orders for supplies, armaments, transportation, and more. Philadelphia-area industries expanded, making the region a major “arsenal for democracy” during the war. With its federal Navy yard, arsenal, and universities, Philadelphia also developed and produced new materials, instruments of communication, electronic tracking, and weaponry. The availability of defense work in cities such as Philadelphia, Camden, and Chester opened opportunities for women and African Americans, including new migrants from the countryside and the South. Much of the demographic movement was temporary, and it was sometimes convulsive, but it helped to redraw the social landscape of the city and region.

The war had sometimes contradictory effects. For example, defense needs created more unity in the region than had existed since the early twentieth century. People mobilizing for a war against Nazism in Europe and against Japanese expansion in Asia shared a common purpose, and they were further united by the effects of federal regulations governing work, consumption, and even entertainment. But the war also created social upheavals and it reduced local autonomy. Philadelphia’s Republican government, which had resisted President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, now found that Washington controlled almost all aspects of city and regional affairs. For example, the federal government treated the area as a single entity for air patrols and air raid drills, and the air command for the whole region was located in the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard. Because of a labor shortage, the War Manpower Commission controlled the allotment of workers to industries in the whole metropolitan area. Other federal agencies with headquarters in Philadelphia managed many aspects of economic and social life in the region. The Office of Price Administration determined retail prices for most consumer products and allotted gasoline and heating oil for individual use.

When the war broke out in Europe, Philadelphia, like the rest of the United States, had high unemployment and many empty factories caused by the Great Depression. After France fell to German armies in June 1940, the Roosevelt administration began a rearmament program that immediately boosted the city’s economy. By the time the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Philadelphia industry had revived enough to mask a long-term trend of industrial decline.

Naval Shipyard Benefits

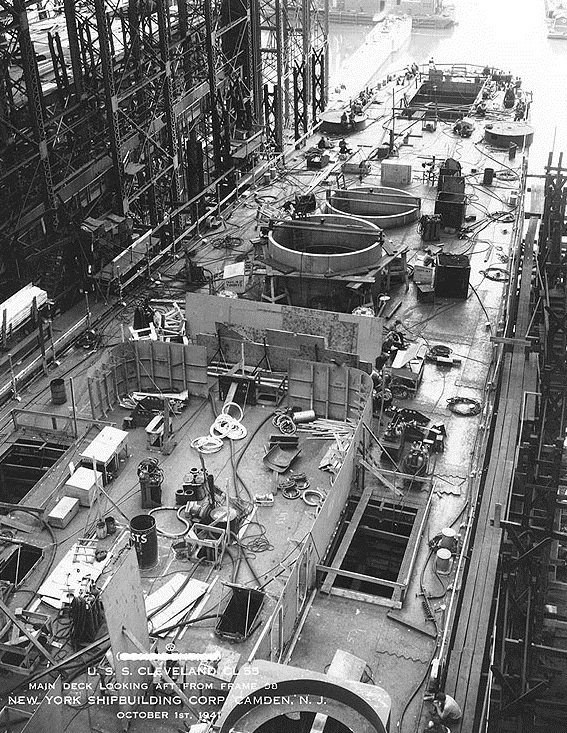

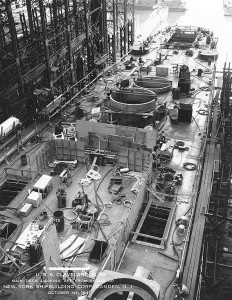

Most immediately, the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, which had been in existence since 1801, benefited from the president’s commitment to building up the Navy. In 1940 and 1941 the Naval Yard also engaged in a clandestine reconstruction of British and other Allied ships damaged by enemy attacks in the Atlantic. The shipyard grew from a few thousand workers in 1939 to 58,000 workers at its peak. The yard even had a naval air field where workers produced aircraft and participated in the development of the first atomic bomb. The Naval Yard’s rebirth benefited suppliers in the metropolitan area, and their work was supplemented by a number of shipyards on the Delaware River including the Cramp Yard in Kensington, the New York Shipbuilding Yard in Camden, and the Sun Shipyard in Chester. In 1944, these shipyards employed more than 150,000 workers and were the largest employers in the metropolitan area. The ships built on the Delaware River were the area’s most important contribution to the war effort.

Because Philadelphia and its suburbs had played such a prominent role supplying munitions in World War I, Washington turned to many of the same facilities for the new conflict. The Frankford Arsenal, which dated from the early 1800s, hired 20,000 workers to manufacture small arms, ammunition, and optical devices. It also engaged in munitions research. Local clothing manufacturers met the needs of the Army Supply Depot, and government turned to other Philadelphia industries to produce tanks, railroad equipment, and heavy weapons. The Baldwin Locomotive Company produced railroad equipment for the Allies and retooled some of its plants to make tanks. The Budd Company in Northeast Philadelphia, which in peace time produced bodies for automobiles, turned out armored cars, tanks, and other equipment. Midvale Steel in Nicetown made armor for the Navy yards. The Radio Corporation of America in Camden, one of the area’s most important electronic companies, produced radios, radar, and other electronic and communications equipment needed by the military.

Roughly 350,000 Philadelphians engaged in defense work, and many thousands more worked in other parts of the region. Camden in New Jersey and Chester, Montgomery, and Bucks Counties in Pennsylvania had large defense contractors. Almost every able-bodied adult who wanted to work found a job, but racial, gender, and ethnic divisions affected when and where individuals found employment and their pay levels. African Americans, who had the highest rate of unemployment during the Depression, found opportunities especially after President Roosevelt issued an executive order prohibiting discrimination in defense hiring. The reluctance of employers to hire African Americans was reinforced by the opposition of labor unions. By the middle of 1943 the actions of the local office of the Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) forced some of the largest defense contractors to reverse their policies. Since the jurisdiction of the FEPC extended over all of Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey, the largest defense contractors in the suburbs began hiring Black employees. American Telephone and Telegraph, the Pennsylvania Railroad, and the Radio Corporation of America revised their hiring practices.

No Black Drivers

Discrimination remained entrenched at the Philadelphia Transit Company (PTC), which ran the buses, trolleys, and subways. Despite repeated pressures from the federal government and local civil rights groups, the company and its union refused to allow Black people to work as drivers. In August 1944, when PTC finally hired seven African American drivers, the union called a strike that tied up the city for a week. President Roosevelt sent in the military to run the transportation services so workers could get to defense jobs, and the government threatened to revoke union members’ draft exemption unless they ended the strike, which led to them returning to their jobs. Before the strike’s conclusion, many Philadelphians feared a race riot similar to the violence that had occurred in Detroit the previous year. But quick action by the NAACP and white civil rights groups, with the cooperation of the newspapers, prevented such an action. Foreshadowing civil rights efforts that would continue after the war, Black activism succeeded in pressuring government to end discrimination across the country, actions that were made possible because the nation needed African Americans’ labor and support. To challenge discrimination, Black organizations worked with white civil rights groups to stage street marches and a newspaper campaign fostering the “Double V,” victory over the Axis abroad and victory over racism at home.

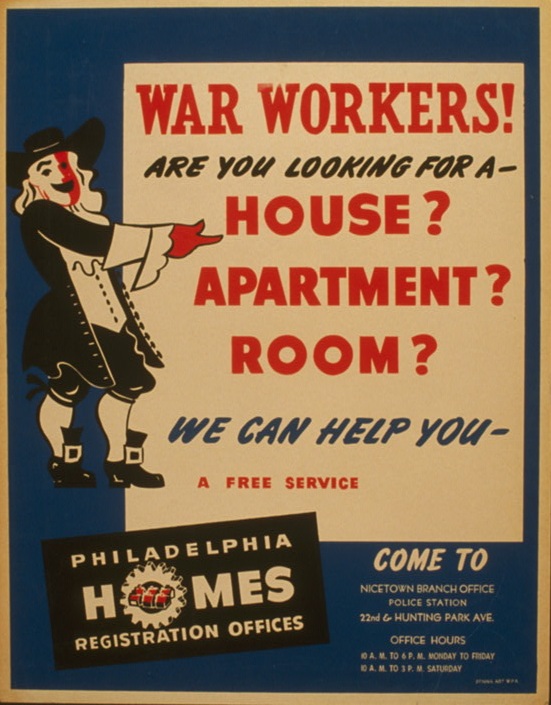

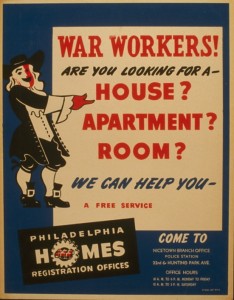

Employment discrimination was only one of many humiliations African Americans suffered during the war. Like other cities, Philadelphia faced an acute housing shortage because of the influx of people looking for work. This affected working-class areas especially as multiple families crowded into small houses, but African Americans lived in the most dilapidated houses of all, often without indoor plumbing.

Throughout the war, as more women entered the workplace, controversy raged over the “proper” place for women and the war’s effects on gender roles. For cultural, ethnic, and social reasons, many Philadelphians worried that letting women work in war plants would threaten the social structure. Several religious organizations charged that working mothers endangered their children. The conservative Republican city government echoed such concerns by refusing to create public day-care centers until near the end of the war. But the shortage of workers ultimately led the War Manpower Commission to recruit women for factories. By 1945, 35 percent of Philadelphia’s women worked outside of the home. Most continued to fill jobs traditionally held by women, but many worked as welders, mechanics, and chemists in ship yards, in the Frankford Arsenal, and at the Pennsylvania Railroad. Before the PTC agreed to hire African Americans as drivers, the company had employed a number of women in that position.

Women and Charities

In a more traditional role, women volunteered to keep Philadelphia’s charities going. The United Service Organizations (USO), which entertained military men in Philadelphia in such centers as the Stage Door Canteen in the basement of the Academy of Music and an open dance floor near City Hall, employed thousands of young women. The USO reached out as well to numerous regional military bases and hospitals, including Fort Dix and the McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey and military hospitals in suburban Philadelphia. Women were active in bond drives and in raising money for social organizations through the United War Fund. In so many ways, women’s involvement in the war gave them their own money to spend, new responsibilities, and new confidence – all of which broadened their social, economic, and political expectations. At war’s end, most women lost or gave up their jobs to returning servicemen and many women settled into family life, sometimes with the benefits of the GI Bill and other federal programs that opened up developing suburbs. Despite a loss of influence that came when women were no longer “needed” in the workplace, their wartime experience laid the grounds for their demands for equal rights in subsequent years.

Although federal propaganda agencies emphasized unity as a necessity for victory, that unity was often missing in Philadelphia. Besides African Americans, other groups experienced discrimination during the war. During the Depression era, Jews often suffered job discrimination and even physical attacks. These attacks increased from 1939 until 1941 during the debate in Philadelphia over whether the United States should remain neutral or provide aid to England and other Allied nations. Opponents of aid charged that the Jews were trying to get the United States involved in another European war. As the debate heated up, Jewish stores were often vandalized, Jewish children often were attacked coming home from school, and there was an arson attack on the home of a West Philadelphia rabbi. Even after Pearl Harbor, Jews continued to face discrimination from groups spreading anti-Semitic literature and practicing job discrimination. Despite service to the war effort on many fronts, Jews continued to face discrimination for years afterwards.

Although no massive relocation occurred on the East Coast to match the forced removal of Japanese from California, Congress classified recent immigrants from Germany and Italy who had not taken out citizenship papers as enemy aliens. The FBI searched their homes and confiscated radios, telescopes, and other instruments regarded as potentially dangerous. Several hundred enemy aliens were held for a time in a facility in southern New Jersey. Enemy aliens were not allowed to work in a defense facilities, which limited their employment opportunities. Despite such restrictions, labor shortages resulted in an unusual occurrence in Cumberland County, New Jersey, as 2,500 Japanese Americans from internment camps in the West were allowed to settle in 1944 to work on the Seabrook Farms and frozen foods factory. Some of them stayed after the war and formed a nucleus of Japanese presence in the region.

Labor strife proved to be another area in which federal efforts to maintain unity often failed. Although nationally unions had agreed to a no-strike agreement, Philadelphia gained a reputation for strikes. During the Depression strikes in textiles and metal manufacturing were common and usually violent. This pattern continued through the war and affected private shipyards, steel mills, and aircraft factories. City workers also went on strike for higher wages. With the support of the War Labor Board, most disputes were settled by arbitration. Attempting to prevent inflation, the War Manpower Commission instituted a wage stabilization program capping wages at 1942 levels. Nevertheless, with full employment and with the average laborer working 48 hours or more a week, Philadelphia workers enjoyed a prosperity that was in sharp contrast to the Depression. To circumvent government wage guidelines, unions often secured fringe benefits such as paid vacations and health benefits which lasted after the war.

City Autonomy Falls Victim to Feds

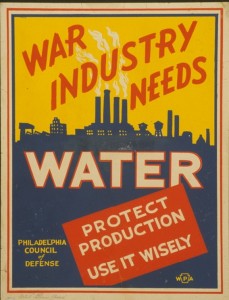

With all kinds of government controls and interference in Philadelphia’s affairs, the autonomy so valued by Mayor Bernard Samuel and the city’s Republican leadership largely disappeared. Decisions made by military commanders stationed in the city largely overturned local authorities. Because of the housing shortage and the refusal of the city government to build public housing, the commandant of the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard ordered the construction of the Tasker Homes in South Philadelphia near the base. By the end of the war, the city reluctantly agreed to build several public housing projects. The same disagreements occurred over civil defense. At first the city government was reluctant to play a role in civil defense, but right before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor it established a Defense Council headed by Mayor Samuel. Particularly in the first two years of the war, the city was on high alert in expectation of an attack from the air. Periodically air raid drills tied up the city as air raid wardens cleared cars and pedestrians from the streets. A general blackout kept homes, stores, and businesses from displaying lights at night.

By early 1945 some of the industries with the highest employment began to lay off workers as the federal government prepared for the end of the war. The shipyards were the first to face retrenchment. The Philadelphia Naval Shipyard reduced its workforce to almost pre-war levels. The Sun Shipyard closed much of its facility and threw thousands of African Americans out of work. When the war ended in August 1945, almost every defense contractor laid off workers. The city never recovered. Many companies, such as Baldwin Locomotive and Budd, survived for a few years but lost out to competitors or in the case of Baldwin to changes in transportation that cut demand for railroad locomotives. The textile industry also collapsed. There were a number of reasons for this failure. During the war the federal government had decentralized its purchases of cloth for uniforms by building factories in the South, where labor costs were lower. While hurting the city, decentralization benefited some of the Philadelphia region’s suburbs, where the War Production Board created new facilities in order to achieve maximum production. For companies seeking factories after the war, this meant a better supply of more efficient facilities in the suburbs than in the city. After World War II Philadelphia’s reputation for labor strife also worked against it. Philadelphia’s dominance in shipbuilding also disappeared. By the time the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard closed in the 1990s all the other major shipyards in the Delaware Valley had shut down. Only one private shipyard survived in the early twenty-first century.

The city of Philadelphia reached its population peak in 1945, but with fewer industrial jobs, its population declined. Regionally, many new jobs were in suburban defense industries such as the Navy’s research center at Willow Grove or the Lockheed-Martin Manufacturing Company in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, or in the RCA facilities in suburban New Jersey. In the 1950 census Philadelphia had 2,071,605 people as a consequence of the war. By the 2000 census the population had declined to 1,517,550, a reduction of about 34 percent in 50 years. Although the 2010 census recorded a slight increase to 1,526,000, the longer-term loss in population made Philadelphia a smaller part of the nine-county metropolitan area surrounding it in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. The city’s share of the population dropped from 60 percent in 1950 to less than 30 percent in 2000. In some ways the suburbs came to look upon the city as their poorer cousin, while the counties outside Philadelphia provided the dynamic economic growth for the region to remain viable.

Although World War II war caused many dislocations and cost the lives of 3,500 servicemen from the city and 1,500 dead from the Pennsylvania counties adjoining Philadelphia, many people look back on this era as a “golden age.” They remember the city’s prosperity, the high wages, and the opportunities the war provided. They remember wartime unity, however illusory, as a marked contrast to the racial and labor conflicts that followed.

Herbert Ershkowitz is Professor of History Emeritus at Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2011, University of Pennsylvania Press.