Colonial Revival

Essay

During the late nineteenth century, a time of great tension, new immigration, and accelerating industrialization, white Euro-Americans sought comfort in the past, specifically the Colonial and Revolutionary eras. In their romanticized interpretation, the founding era was defined by simplicity, domestic industry, and unity—qualities in direct contrast to the tumultuous Civil War and its aftermath. They expressed nostalgia for the Colonial and Revolutionary eras through architecture, landscape design, and material culture in a popular movement known as the “Colonial Revival.” The origins of the movement can be traced to the 1876 centennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, which presented an opportunity to reunify the country by showcasing American ingenuity and culture to the world at the Centennial Exhibition held in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park.

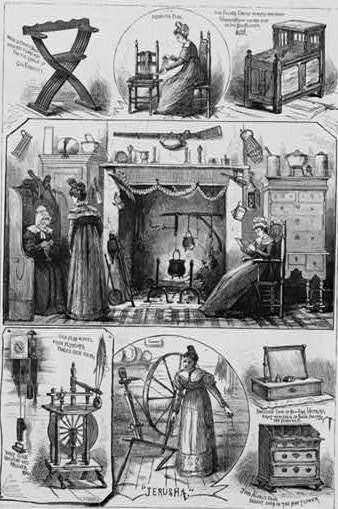

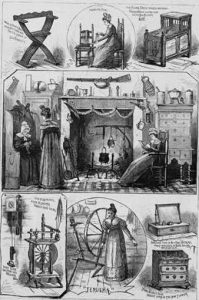

The Centennial Exhibition featured exhibits of American technological advances alongside vignettes from the Colonial era. “The New England farm-house,” for example, presented a picture of domestic industry, complete with tools for traditional arts like candle making and an “old flax wheel from Plymouth.” The state of New Jersey highlighted its revolutionary history by reconstructing the Ford Mansion, the Morristown headquarters of George Washington (1732-99). These exhibits encouraged Americans to grasp a shared past, but the past they presented did not reflect colonial America’s diversity; instead, Anglo-American contributions dominated the conversation.

Although the Centennial Exhibition ended after six months, interest in romanticized, Anglicized versions of early-American architecture, landscapes, and decorative arts continued and evolved through the late nineteenth and twentieth century. Philadelphia became a geographic touchstone in the Colonial Revival movement as collectors like Henry Francis du Pont (1880-1969) turned their attention toward American decorative arts and furniture. At the same time, writers like Harold Eberlein (1875-1965), Anne Hollingsworth Wharton (1845-1928), and Robert (1860-1923) and Elizabeth (1871-1936) Shackleton produced hundred of books on the decorative arts and architecture, feeding the national obsession with all things “colonial.”

Architectural Characteristics

As the Colonial Revival gained momentum, nineteenth- and twentieth-century architects studied the Delaware Valley’s early English, German, Dutch, and Swedish buildings, focusing on their common elements to create a distinct Colonial Revival architectural style. Those elements included double-hung windows with shutters; hipped, gable, or gambrel roofs; and local building materials, such as stone. These features dotted the landscape of the Philadelphia area through the work of architects like Richardson Brognard Okie (1875-1945). Born in Camden, New Jersey, Okie completed his studies in architecture at the University of Pennsylvania during the first wave of the Colonial Revival movement. His designs of private residences, such as the H.B. Du Pont house in-Wilmington, Delaware, featuring stone exteriors, prominent chimneys, wide floorboards, and hand-wrought nails—hallmarks of his Pennsylvania farmhouse style. Another Philadelphia architect, Charles Barton Keen (1868-1931), designed Colonial Revival houses for wealthy Philadelphians then extended his practice along the East Coast.

While some architects employed vernacular building techniques, others paid homage to high-style Georgian architecture, with its symmetrical brick facades, central cupolas, and entrances with pediments. Architects Frank Miles Day (1861-1918) and Charles Z. Klauder (1872-1938) opted for stately Georgian grandeur when they designed “The Green” for the University of Delaware in 1917, giving an architectural nod to Delaware’s status as the first state. Whether they were going for the quaint charm of vernacular architecture or the classical elegance of Georgian architecture, Colonial Revival architects featured common eighteenth-century characteristics to give an impression of the past, rather than reproduce it.

The National Preservation Movement and the Colonial Revival

In the first decades of the twentieth century, architects who spearheaded the Colonial Revival style also participated in an emerging national preservation movement, working with new organizations like Colonial Williamsburg and the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities to bring Colonial buildings back to their former glory. Philadelphia was also an epicenter of historic preservation projects: Fiske Kimball (1888-1955), director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, led the restoration of Fairmount Park’s eighteenth-century mansions. The National Society of the Colonial Dames of America installed a Colonial Revival garden on the grounds of Stenton, the home of James Logan (1674-1751). For his part, Okie took on the restoration of the Betsy Ross House. The Women’s Committee of the Sesquicentennial International Exposition (1926) also selected Okie to head the reconstruction of Philadelphia’s Colonial High Street.

While these projects drew praise and adoration by many, they frustrated ethnic groups that had been steamrolled by the Anglocentric narrative of the preservation movement. Determined to showcase their contributions to American history, ethnic heritage groups organized their own celebrations and projects. In 1913, African Americans in Philadelphia and other cities across the country celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. In 1926, Dr. Amandus Johnson (1877-1974) founded the American Swedish Historical Museum in South Philadelphia to honor the contributions of America’s early Swedes. Despite these and other efforts, nativist sentiments persisted in Philadelphia, and the historical narrative remained relatively unchanged.

Historians also voiced concerns as some preservation projects favored aesthetics over historical accuracy. In the 1930s, Okie headed the reconstruction of Pennsbury Manor, the country estate of William Penn (1644-1718) in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. University of Pennsylvania historian Albert Cook Myers (1874-1960) withdrew his support from the project when he determined it reflected Okie’s personal taste rather than the archaeological and historical evidence. Myers went so far as to call the project a “monstrosity of vicious error.” Despite criticism from Myers and others, the reconstructed estate opened to the public in 1939. While the reconstruction of Pennsbury Manor and other historic preservation projects inspired public interest in the Colonial era, they also blurred the lines between historical and stylized impressions of the past.

The New Deal and Public Architecture

The Colonial Revival movement maintained popularity in the 1930s as a new crisis, the Great Depression, gripped the nation. Colonial Revival architecture continued in the form of new public buildings through the New Deal initiatives of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945). Programs including the Public Works Administration and Works Progress Administration funded the construction and improvement of libraries, post offices, and public schools, such as the Pierre S. Du Pont High School building (later the Pierre S. Du Pont Middle School) in Wilmington, Delaware, and Jenkintown Elementary School in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania. Government funds also went toward the improvement of existing Colonial structures, including Independence Hall; the Trent House in Trenton, New Jersey; and the Vernon-Wister House in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia.

Buildings with brick facades and central cupolas offered a familiar, comfortable aesthetic as an alternative to the sleek, modern Art Deco architecture of the 1920s. Once again, the Colonial Revival movement served as a distraction from the hardships of modern life and encouraged Euro-Americans to look to a romantic version of the past for hope.

Beyond World War II

After the Second World War, suburban neighborhoods inspired a new wave of Colonial Revival architecture—one that was more economical and accessible to the growing middle class. The two Levittown suburbs in Pennsylvania and New Jersey advertised the 1957 “Colonial” as one of six house models. The two-story home offered traditional appeal with room for modern amenities, including a garage. While mass-produced “neocolonial” homes lacked the decorative elements of earlier Colonial Revival homes, they provided buyers with a simplified version using cost-effective materials. Families could continue the theme into the interior living spaces with midcentury versions of Colonial Revival furniture and color palettes. Once again, ideas of peaceful, colonial domesticity hit a chord with post-war, white Americans. However, as before, the Colonial Revival served as a figurative as well as literal façade, this time masking anxiety over suburban housing integration. The same year the “Colonial” debuted, the first African American family moved into a Levittown, Pennsylvania, home. The severe harassment they faced showed their neighbors did not mean to extend “American dream” (and the dream home) to all Americans.

While modernism dominated aesthetics in the 1960s and 1970s, the nation’s Bicentennial in 1976 resurrected Colonial Revival style and placed Philadelphia in the spotlight once more. Interest in Colonial history ebbed and flowed through the rest of the twentieth century, but the Colonial Revival remained in the country’s national consciousness. It peaked during times of social unrest, national crises, and historical milestone anniversary celebrations—moments when white Americans looked for common virtues and ways to maintain familiar social orders. Once maligned for its historical inaccuracies, in the late twentieth century the Colonial Revival became a subject of study and interest among historians. As a physical representation of American virtues and a hub of Colonial history and lore, Philadelphia remained at the fore of the Colonial Revival movement.

Danielle Lehr Schagrin is the former Education Program Coordinator at Pennsbury Manor, the reconstruction of William Penn’s country estate. She completed an internship with the Colonial Williamsburg Teacher Institute and holds an M.A. in History with a concentration in public history from Lehigh University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Colonial Revival Style, 1880s-1940 (National Park Service)

- Colonial Revival Style, 1880-1960 (Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission)

- Colonial Dames? Yes, Still Active (And Growing) on Latimer Street (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- 1926 Meet 1776 at the Philadelphia Sesquicentennial (Alice T. Miner Museum)

- Patriotic Etiquette at the Liberty Bell — 1919 edition (PhillyHistory Blog)