Independence Hall

Essay

Originally the Pennsylvania State House, the eighteenth-century landmark associated with the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution came to be known as Independence Hall as it evolved from a workplace of government to a treasured shrine, tourist attraction, and World Heritage Site. Its history encompasses more than 275 years of struggles for freedom and public participation in creating, preserving, and debating the founding principles of the United States.

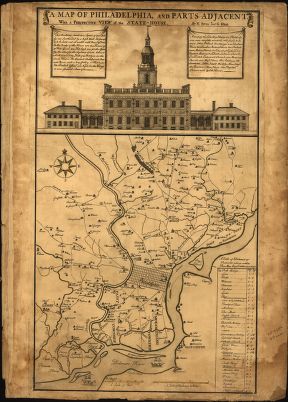

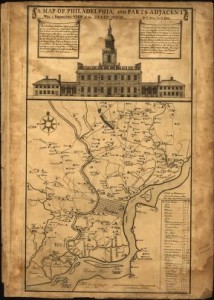

The history of Independence Hall dates to 1729, when the Pennsylvania Assembly authorized construction of “a House for the Assembly of this Province to meet in.” The site chosen, on Chestnut Street between Fifth and Sixth Streets, was then on the outskirts of Philadelphia and therefore pulled the city’s development westward. In architectural style, the building that began construction in 1732 was Georgian—a common choice for American public buildings but also a statement of British elite culture at a time when Pennsylvanians were concerned about large in-migrations of Germans and Scots Irish.

Assembly Speaker Andrew Hamilton (1676-1741) led the committee to select the site and is credited with the building’s design, which closely resembled architectural pattern-book plans for English country houses. Edmund Woolley (c. 1695-1771), a member of the Carpenters’ Company, supervised the craftsmen and laborers who built the structure, which was ready for use by the Assembly by 1736. In 1749, the Assembly again called upon Woolley to add a tower and steeple to the south side of the building, thereby creating the building’s distinctive, church-like silhouette and providing a place to hang a new bell—the same bell that later became known as the Liberty Bell.

The Pennsylvania State House served many purposes in its first half-century, as the seat of provincial government, a banquet hall for occasions such as celebrations of birthdays of British monarchs, and a meeting place for learned societies such as the American Philosophical Society and the Library Company of Philadelphia. But its lasting place in American history was secured during the era of the American Revolution, when Pennsylvania’s central location and relatively moderate politics made Philadelphia the logical gathering place for the First and Second Continental Congresses.

State and National Governments

Despite resistance to independence by the Pennsylvania Assembly, the Second Continental Congress met in the State House beginning in May 1775, and in the east room on the first floor resolved to break from Great Britain on July 2, 1776, and approved the Declaration of Independence on July 4. Within the State House, Pennsylvania government also changed. In July 1776, a Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention produced a constitution regarded as the most democratic among all the former British colonies, and in 1780, the Pennsylvania Assembly passed the nation’s first law mandating the gradual abolition of slavery. The State House served as capital of both the state and national governments for the duration of the War for Independence, interrupted by the British occupation of Philadelphia in 1777-78, when the building served as jail and hospital ward for American prisoners.

A second hallmark event in the building’s history occurred in 1787, when the State House served as meeting place for the Constitutional Convention, which convened in May and completed its work on a new frame of government on September 17. Activity in and around the State House then shifted to whether Pennsylvania would ratify the document, and violent street confrontations occurred between supporters (Federalists) and dissenters. After lengthy public debates by a ratifying convention in the State House, focused on issues such as the lack of guarantees for individual rights, Pennsylvania became the second state (after Delaware) to ratify the U.S. Constitution.

The State House continued as the seat of Pennsylvania government through the 1790s, when Philadelphia also served as the nation’s capital, but became the “old” State House after Pennsylvania followed its westward-growing population by moving the state capital to Lancaster in 1799 and later to Harrisburg. When the federal government also left Philadelphia for the new District of Columbia in 1800, the old State House faced an uncertain future. Through the 1790s and the early decades of the nineteenth century, the second floor gained a new purpose as the home of Charles Willson Peale’s (1741-1827) Museum, which aimed to cultivate a new national culture through appreciation of the arts and natural sciences. But the building and square around it became surplus state property at risk of being sold for redevelopment as building lots.

Altered Architecture

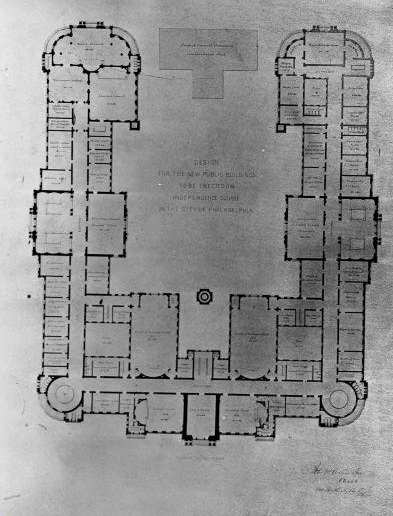

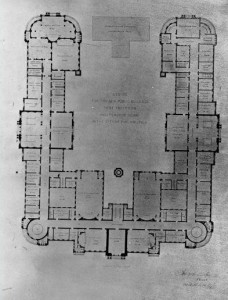

Philadelphians also showed little regard for the original fabric of the old State House when, in 1812, they allowed the structure’s wings and arched piazzas to be replaced by rows of brick buildings for city offices. However, when state proposals in 1813 and 1816 called for selling off the State House square, Philadelphia city officials acted to preserve the building and opened a period of local guardianship that continued until the mid-twentieth century. The city agreed to buy the building and square from the state in 1816, an act regarded as important in the history of historic preservation in the United States.

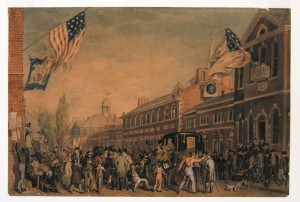

When the Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834), a hero of the American Revolution, visited the United States in 1824, he was welcomed to Philadelphia at the old State House. In the process of planning this event, Philadelphians began to refer to the first-floor east room as “the Hall of Independence” and “Independence Hall”—a name that gradually came to be applied to the entire building. The surrounding square was named Independence Square in 1825, when the city also gave names of historic figures (Washington, Franklin, Rittenhouse, and Logan) to other squares. In 1828, Philadelphia City Councils also ordered a new steeple for the old State House and insisted that it resemble the original, which had rotted away four decades before. Such actions reflected a growing dedication to preserving the memory of the American Revolution as the founding generation passed from the scene.

As a public building associated with the nation’s founding events but surviving in the midst of a growing, industrializing city, Independence Hall served as a focal point for engaging the political, economic, and social issues of the nineteenth century. Other than the first-floor room where independence was declared, through the mid-nineteenth century the building housed courtrooms where judgments determined the freedom or loss of freedom for individuals accused of crimes; apprentices who sued for release from their contracts; and African Americans suspected of being fugitives from slavery.

Just Outside, Historic Gatherings

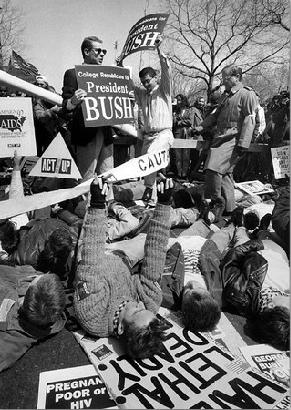

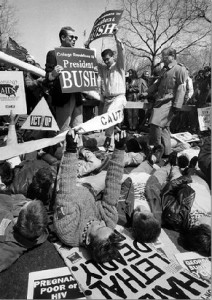

Outside in the square, laborers demonstrated for improved working conditions, immigrants demonstrated in sympathy with revolutions in Europe, and Frederick Douglass (1818-95) spoke against slavery in 1844. In 1876, Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) and other women’s rights activists distributed a Declaration of Rights of Women. Independence Square remained a forum for public dissent until the early twentieth century, when the City of Philadelphia responded to a planned demonstration by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) by restricting activity to officially designated “patriotic purposes.” After the creation of Independence National Historical Park in the mid-twentieth century, the National Park Service tolerated demonstrations during the Civil Rights and Vietnam eras, but federal regulations subsequently placed new restrictions on the use of the square, especially following attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001.

Under the guardianship of Philadelphians, Independence Hall gradually transformed from a working government building to a national shrine, with traces of other local uses often erased in the process. The first-floor east room became a shrine to the founding fathers in 1854 under the sponsorship of nativist politicians, who gained control of the city government that year and created new City Council chambers on the second floor. During the Centennial celebration of 1876, the entire first floor of the building became the “National Museum,” featuring portraits and early-American artifacts. At the end of the century, when the City Councils left the building for the new City Hall, the Daughters of the American Revolution renovated and redecorated the second floor in Colonial Revival style. The despised “row buildings” that had flanked the central structure since 1812 were replaced by new, graceful archways that resembled the original piazzas and opened a view and passageway from Chestnut Street to the square.

With the building now fully dedicated to historic purposes, in the first decades of the twentieth century Philadelphians also advocated creating expanded parks to buffer the treasured landmark from its dense, heavily industrialized surroundings. They succeeded. The resulting Independence Mall and Independence National Historical Park at mid-century led to demolition of six city blocks of buildings not regarded as “historic,” an urban renewal project that also opened a new era of professional stewardship by the National Park Service. Independence Hall gained additional recognition in 1979, when it was designated a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Independence Hall, the scene of events of national and international importance, also influenced the development and redevelopment of its home city and served as an impetus for the growth of the region’s tourist industry. By the first decades of the twenty-first century, Independence Hall anchored a historic district devoted to tourism and civic education, including the National Constitution Center, the Liberty Bell Center, the Independence Visitor Center, the National Museum of American Jewish History, and a memorial to the President’s House and individuals enslaved there by George Washington. Surrounded and dwarfed by larger institutions, Independence Hall is accessible by guided tours led by the National Park Service. Expertly restored, it is experienced as a time capsule of the past, but it has many stories to tell.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and the author of Independence Hall in American Memory(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Philadelphia could be first American city to receive world honor (WHYY, March 30, 2014)

- Marking 50 years of struggle and a week of equality, Annual Reminders to march again in Philly (WHYY, June 29, 2015)

- Protesters to shine DNC spotlight on health care, energy, political art at Independence Mall (WHYY, June 22, 2016)