Tourism

Essay

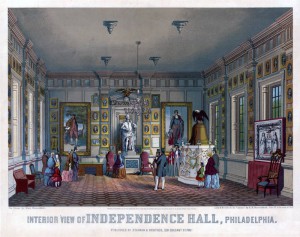

Philadelphia has been a tourist destination since leisure travel emerged as a common pastime for the middle and upper classes in the nineteenth century. By the twenty-first century, the region’s economy depended heavily on tourism to Philadelphia and nearby destinations such as the Brandywine Valley, Valley Forge, and the Jersey and Delaware shores. Historic sites of the colonial era and American Revolution attracted many travelers, but these assets also created a challenge for promoters seeking to portray Philadelphia as not just a place of historical interest but as a lively, exciting place to spend a vacation.

“Tourism” in the sense of travel for no reason other than seeing the sights did not become a phenomenon in the United States until the 1820s, when improvements in transportation and accommodations made touring possible for people with wealth and leisure time. Precedents existed, however. From the time of Philadelphia’s founding in the 1680s, the growing city attracted individual travelers and migrants from other colonies and abroad. Visitors also sought out nearby resorts such as the healthful mineral waters at Yellow Springs in Chester County and Bristol Springs in Bucks County, both popular destinations in the eighteenth century. By the 1810s, Cape May at the southern tip of New Jersey began to develop into a resort for affluent families who traveled on ships from Philadelphia, Wilmington, Trenton, and Baltimore to relax in hotels by the sea.

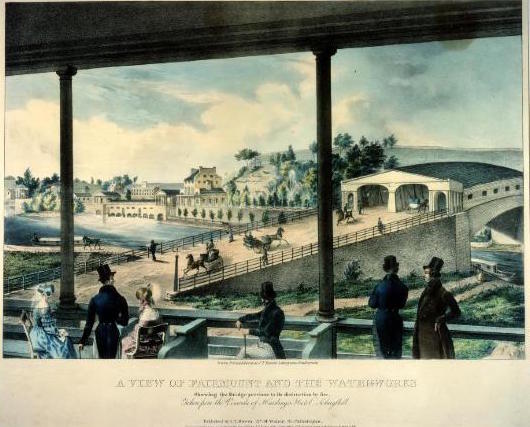

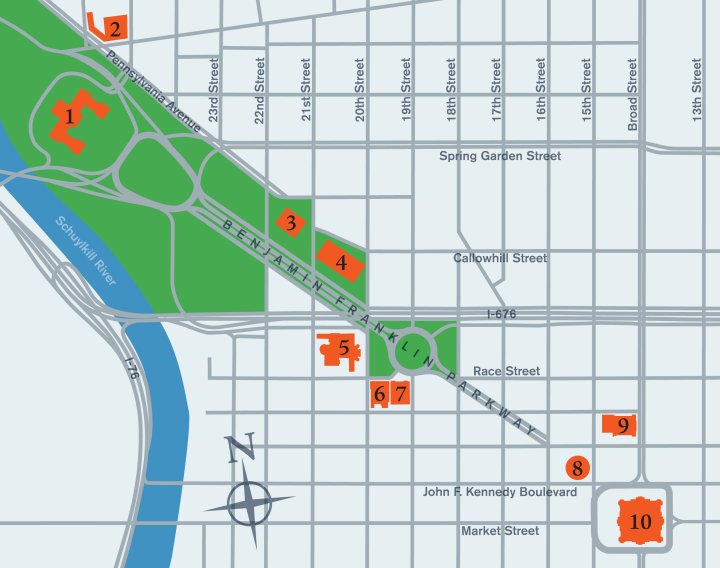

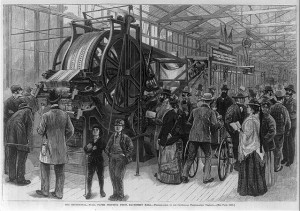

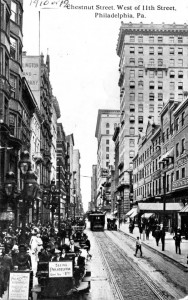

In the early nineteenth century, tourists favored sites of pastoral scenic beauty more than city destinations, so it is likely that Philadelphia sent out more tourists than it received. Nevertheless, the city began to develop an infrastructure for tourism, including the city’s first full-fledged hotel, the United States Hotel, opened in 1828 on Chestnut Street opposite the Second Bank of the United States. Philadelphia publishers also began to produce guides to the city’s sights. Tourists who came to Philadelphia sought out new institutions and immersive experiences, as they did in other major cities. They toured innovations such as the Fairmount Water Works and Eastern State Penitentiary and visited the monumental Laurel Hill Cemetery. They took in exhibitions at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts or Charles Willson Peale’s museum, attended theatrical performances, and explored nature in public gardens and along the Wissahickon Valley. Often they attended worship services at a variety of churches or observed court proceedings. Some also sought out places with historic associations, but the old Pennsylvania State House, where Americans declared independence from Great Britain in 1776, remained in use for courts and other purposes. Only gradually over the nineteenth century did this building become known as Independence Hall and fully presented to the public as a historic site.

In the 1830s, railroads began to open tourism to the emerging middle class. Although far from comfortable for long-distance travel, by 1840 rail lines connected the Mid-Atlantic region to most of the Atlantic Coast from New Hampshire to the Carolinas. Railroads helped to open the tourism potential of the Jersey Shore, as entrepreneurs in the 1850s extended rails from Philadelphia and New York to new resorts such as Atlantic City and expanded links to established destinations such as Cape May. Railroads also enabled countryside excursions from Philadelphia to the Brandywine Valley and Valley Forge.

Vacations of One or Two Weeks

The “vacation” of one or two weeks a year became more common among middle-class Americans from the 1850s through the 1870s, with the time away from work often spent at resort hotels. This increased tourism to seaside areas such as the Jersey Shore but did not significantly benefit Philadelphia and other cities, where travel continued to be dominated by people doing business or visiting family and friends. Vacationers who opted for touring, rather than resort stays, often sought to see as many sights as possible within their limited time. This created a challenge for Philadelphia that persisted for decades: leisure travelers seldom stayed very long in any one place, limiting their economic impact.

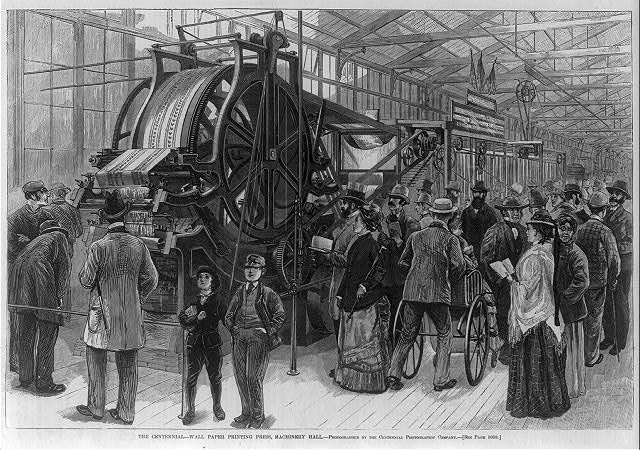

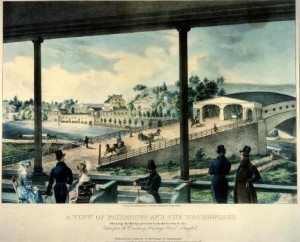

Philadelphia helped to usher in a new era for urban tourism when it staged the first full-scale world’s fair in the United States, the Centennial Exhibition of 1876. World’s fairs, enormously popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, gave tourists an incentive to visit the host cities and fulfilled desires to pack many experiences into a short vacation. The Centennial Exhibition in Fairmount Park attracted more than 10 million visitors. Although that number included local residents and repeat visits, the extent of out-of-town tourists is suggested by the construction of eight temporary hotels adjacent to the fairgrounds, the largest offering 1,325 rooms, to supplement fifty-one downtown hotels each with fifty rooms or more. Railroads also encouraged tourism by offering special fares. World’s fair tourists included not only adults but also entire families.

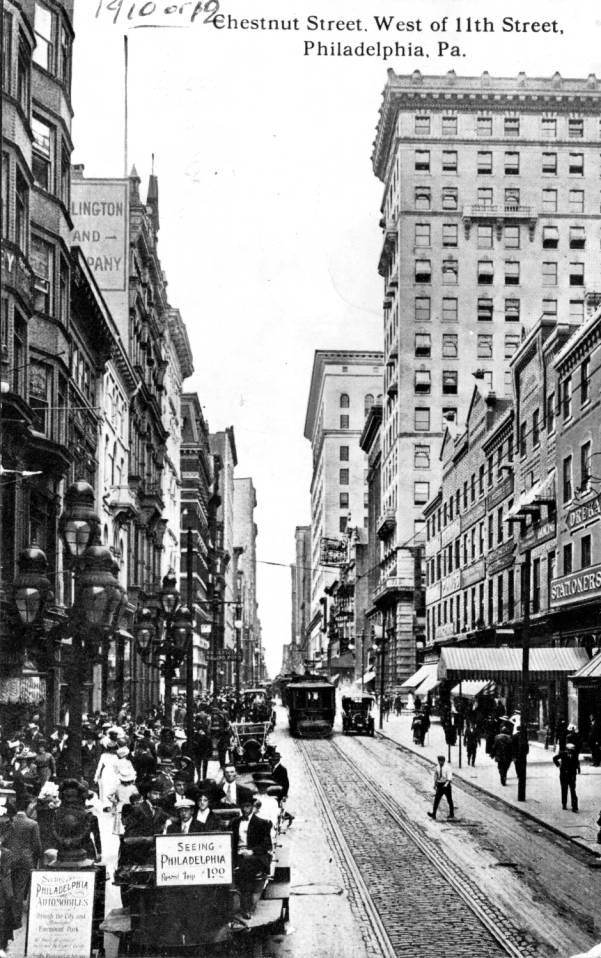

As a celebration of the one hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the Centennial highlighted the dual character of Philadelphia that persisted into the twentieth century as an opportunity but also a challenge for promoters. The region had historic sites of the American Revolution in abundance, and their appeal could not be denied. However, Philadelphia also was a booming industrial city seeking to highlight modern progress more than the past. In 1876, Independence Hall attracted visitors with new exhibits styled as the “National Museum” and took center stage for the Fourth of July, but the world’s fair of modern marvels drew visitors’ greatest attention. By the turn of the century, Philadelphia’s new City Hall (completed in 1901) allowed government functions to finally move out of Independence Hall, leaving it to serve solely historic purposes for the first time. The Betsy Ross House in the 400 block of Arch Street also became an attraction after a fund-raising campaign in the 1890s saved it from demolition. However, City Hall helped to pull civic activity westward to Broad Street’s emerging corridor of skyscrapers and the city’s grandest new hotel, the Bellevue-Stratford (opened in 1904). When the nation celebrated the Declaration of Independence again in 1926, organizers of the Sesquicentennial International Exhibition erected a faux-Colonial “High Street” amid the attractions in South Philadelphia and a giant electrified Liberty Bell across Broad Street. Visiting authentic eighteenth-century landmarks required a side trip away from the fair to the oldest sections of the city.

The forces of past and present combined to reshape the tourism landscape of Philadelphia and the nearby region in the first half of the twentieth century. City planners and architects, seeking alternatives to deteriorating urban conditions, carried out projects such as the Benjamin Franklin Parkway (built 1917-26) and joined with patriotic citizens to support creation of Independence National Historical Park (authorized by Congress in 1948). These projects, requiring demolition of many blocks of eighteenth and nineteenth-century structures, created new, attractive cultural districts and settings for the large-scale events that became a hallmark of Philadelphia later in the century. On a smaller scale, meanwhile, the historic preservation movement sought to sustain material connections to the past in an era of rapid change. Preservation efforts assured that Philadelphia would retain Elfreth’s Alley, the 1765 home of Mayor Samuel Powel (1738-93), and other colonial-era sites in the city and region. Preservationists intervened to prevent the former home of the Franklin Institute, a Greek Revival building designed by John Haviland (1792-1852), from being demolished for a parking lot; instead, radio manufacturer Atwater Kent (1873-1949) bought the structure at 15 S. Seventh Street and gave it to the city for a local history museum (opened in 1941 as the Atwater Kent Museum, later renamed the Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent). The inheritors of a number of private estates in the region also created public museums and gardens, notably the DuPont family’s Longwood Gardens and Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library in the Brandywine Valley of Pennsylvania and Delaware.

Government Looks to Leisure Travel

With an increasing stock of attractions and with tourism growing, first from improvements in comfort on the railroads and then with the advent of automobiles, business and government leaders moved to capitalize on the economic potential of leisure travel. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, American cities competed vigorously for industrial and business opportunities. Groups such as the Philadelphia Board of Trade had long promoted the city as a meeting place for national conventions. Yet Philadelphia lagged behind Boston, another rival similarly stocked with historic sites, in attracting leisure travelers. In the 1920s, with urging from the hotel industry, the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce devoted increasing effort to promoting tourism and school field trips to historic sites. In 1929, the Chamber’s Convention and Exhibition Bureau became the Convention and Tourist Bureau; renamed the Philadelphia Convention and Visitors Bureau in 1945, the organization became an independent entity in 1951.

By mid-century, tourism was not only a local concern but also the dedicated purpose of agencies in federal and state governments. Thus Philadelphia became embedded in a regional network of tourist sites managed by government agencies as well as private operators, connected by the movement of tourists among sites they wished to see. State agencies invested in advertising to potential tourists, erecting historical markers along highways, and managing sites such as Washington’s Crossing on both sides of the Delaware River in Pennsylvania and New Jersey; Pennsbury Manor in Bucks County; Valley Forge in Chester County (which became a national historical park in 1976); and Batsto Village in South Jersey.

The years following World War II propelled a surge of tourism made possible by automobiles and driven by the popularity of family vacations. At a time when the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union placed a high value on the “American way of life,” families sought to instill civic values in their children with trips to historic sites and symbols, including Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell. The construction of Independence National Historical Park underway during the 1950s did not deter vacationing families, and the reform administrations of Mayors Joseph S. Clark (1901-88) and Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974) viewed tourism as integral to revitalizing the city in the wake of the Great Depression and World War II. In 1951, a new city charter established the Office of City Representative, whose responsibilities included promoting Philadelphia as well as representing the mayor at ceremonial events.

During the 1950s Pennsylvania helped promote Philadelphia with depictions of families visiting Independence Hall on the state’s official tourism map, but Philadelphia boosters sought to modernize the city’s appeal. In 1960 the Convention and Visitors Bureau opened a new headquarters and visitor center resembling a space-age flying saucer near the foot of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, a mile west of the “historic district.” In addition to the Convention and Visitors Bureau and the City Representative, tourism development efforts included a Philadelphia Area Council on Tourism (PACT) created in 1961 by Dilworth but not fully funded by City Council. The agencies sometimes worked together, but at other times operated without coordination. Despite their efforts, a 1967 study found that visitors considered Philadelphia an above-average place to visit historic sites, but not an especially exciting place for a vacation. Philadelphians themselves seemed to need to be convinced of the city’s charms, as evidenced by a billboard and slogan for a Chamber of Commerce event in 1972: “Philadelphia isn’t as bad as Philadelphians say it is.”

The Bicentennial Quandary

Although the approaching 1976 Bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence offered a new opportunity to capitalize on the region’s history, local ambitions competed with decentralized, nationwide celebrations. Fears of urban unrest stoked by Mayor Frank Rizzo (1920-91) and an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease undercut Philadelphia’s appeal. Nevertheless, Bicentennial projects expanded the region’s array of tourism attractions and services, including the opening of the Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum (later renamed the African American Museum in Philadelphia), the National Museum of Jewish American History, the Mummers Museum, a new Visitor Center for Independence National Historical Park, and a modern pavilion to show off the Liberty Bell.

The sense that Philadelphia was not doing enough to benefit from tourist dollars persisted into the 1980s and 1990s, an era when globalization made place-marketing a key strategy for localities seeking to differentiate themselves and attract investment. Philadelphia’s painful transition from industrial powerhouse to post-industrial city raised the stakes. To meet the challenge, Mayor Edward G. Rendell (b. 1944) created the Greater Philadelphia Tourism Marketing Corporation (GPTMC, later rebranded Visit Philadelphia) in 1996 to target leisure travelers. Operating separately from the Convention and Visitors Bureau, the new agency took a regional approach to “Philadelphia and Its Countryside” and formed partnerships with similar organizations in the region: the Valley Forge Convention and Visitors Board, Visit Bucks County, and the Brandywine Conference and Visitors Bureau, among others. Beyond this five-county Pennsylvania-based collaboration, similar place-marketing organizations operated in South Jersey, including the South Jersey Tourism Corporation and the Jersey Shore Convention and Visitors Bureau, and in Delaware. The tourism marketers diversified their appeals beyond the traditional Caucasian family vacationer by reaching out to African Americans (through the Multicultural Affairs Congress of the Convention and Visitors Bureau, formed in 1987), gays and lesbians (“Get Your History Straight and Your Nightlife Gay” campaign, GPTMC, 2003), and international travelers. Seeking to advance Philadelphia as an international brand, a Global Philadelphia Association formed in 2010 and five years later succeeded in making Philadelphia the first United States member of the Organization of World Heritage Cities, composed of cities with sites on the World Heritage List of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (in Philadelphia’s case, Independence Hall).

From the 1990s into the early decades of the twenty-first century, the Philadelphia region’s tourism industry created an increasingly elaborate and interdependent infrastructure to attract leisure travelers and convince them to make more than a brief stop to see the Liberty Bell on their way between Washington, D.C., and New York City. With millions of dollars in investment from government, private foundations, and individual donors, underused plazas at Independence National Historical Park evolved into a civic campus with a new exhibit hall for the Liberty Bell, the National Constitution Center, and an Independence Visitor Center to promote the region. Waterfront development in Camden featured the New Jersey State Aquarium, a concert amphitheater, a minor league ball park, and the Battleship New Jersey. Hotels proliferated, especially within walking distance of the Pennsylvania Convention Center (opened in 1993 and expanded in 2011). Temple University established a School of Tourism and Hospitality Management in 1998, and the Association of Philadelphia Tour Guides (formed in 2008) launched a training and certification program in 2011. In the Germantown section of Northwest Philadelphia, historic house museums banded together as Historic Germantown and promoted “Freedom’s Backyard.”

Broadening the City’s Appeal to Tourists

Throughout the region, historic sites, museums, and other cultural organizations sought to attract local residents as well as visitors with varieties of programming. Places that appealed to nineteenth-century tourists because they were new and innovative, such as Eastern State Penitentiary and the Fairmount Water Works, gained new purposes as historic places and centers for education. Tourists could focus their attention on Philadelphia’s place in the nation’s history, to be sure, but the appeal of the city and the region also built upon the arts, on museums and sites focusing on science and medicine, on sports and recreation, on attractions and activities for children, and on a surge of innovative restaurants attracting national and international attention. Beyond the annual celebration of the Fourth of July–expanded and branded as Welcome America–tourism swelled during such mega-events as concerts (from Live Aid in 1985 to the Labor Day-weekend Made in America music festival introduced in 2012), the visits of two popes (John Paul II in 1979 and Francis in 2015), the annual Philadelphia Flower Show and similar extravaganzas, and recurring sports rivalries such as the Army-Navy game.

As a major sector of the region’s post-industrial economy, tourism could be vulnerable to setbacks during times of recession or national emergency, such as the attacks on the United States that occurred on September 11, 2001. Despite these challenges, tourism to the region appeared to have reached new heights by the second decade of the twenty-first century. For the period from 1997 to 2014, Visit Philadelphia reported a 90 percent increase in overnight leisure travelers to its five-county Pennsylvania region, from 7.3 million to 13.9 million (a total exceeding the 10 million visitor count of the Centennial in 1876). Economically, according to the agency’s calculations, this translated to support for 92,000 jobs and $655 million in local and state tax revenue. Once a casual pastime of the wealthy, tourism in the twenty-first century became a more widespread and diverse phenomenon but took place within the realms of sophisticated place-marketing and global competition.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and Editor-in-Chief of the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. She is the author of Independence Hall in American Memory (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002) and Capital of the World: The Race to Host the United Nations (NYU Press, 2013). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Two decades of marketing paying off for Philadelphia tourism (WHYY, May 12, 2011)

- App helps locals and tourists alike find Philly history they weren't even searching for (WHYY, January 2, 2013)

- Philadelphia enlists everyday 'ambassadors' to welcome tourists (WHYY, July 9, 2013)

- Google camera backpack could help Bucks County bring in more tourists (WHYY, May 25, 2015)

- Echoing tourism ad, HollabackPhilly respectfully disagrees with approach (NewsWorks, April 28, 2014)

- VisitPhilly officials will fix Germantown tourism oversights, tour neighborhood (WHYY, June 11, 2014)

- Pennsylvania turns to happiness for new state tourism motto (WHYY, March 8, 2016)

- New Jersey considers spending more on arts, historic heritage and marketing (WHYY, June 10, 2016)

- Extravaganzas and inconveniences: Philly becoming host with the most (WHYY, May 1, 2017)

Links

- Research on Travel and Tourism in the Philadelphia Region (Visit Philadelphia)

- Visit Philadelphia

- Philadelphia Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Bucks County Conference and Visitors Bureau

- Chester County's Brandywine Valley

- Destination Delco

- Visit South Jersey

- Valley Forge

- Visit New Jersey

- Visit Delaware

- Wilmington and the Brandywine Valley

- Philazillas Commercial (Visit Philadelphia)

- The Negro Motorists Green Book (New York Public Library)

- George Brightbill Postcard Collection (Digital Exhibit, Library Company of Philadelphia)