Socialist Party

Essay

The Socialist Party had a wide-ranging impact on the Philadelphia region, from its influence in garment unions, to free speech battles during the First World War, to the administration of the industrial city of Reading in Berks County. This big-tent organization of radicals, which brought in militant labor unionists and social democratic electoral reformers with moralistic orators, electoral campaigns, and advocacy for socialism, took root within Philadelphia, southeastern Pennsylvania, and to a small degree in Camden, New Jersey. The national Socialist Party was founded in 1901, and Philadelphia quickly became one of its centers with large hubs in the Kensington neighborhood and eventually the textile mills of Reading.

Philadelphia Socialists had a strong presence in immigrant communities, among garment and other textile labor militants, and in the anti-war free speech advocates of World War I. The high-water mark of Socialists in Pennsylvania arrived with the Socialist electoral successes in Reading from 1927-36, when they won the mayorship, several council seats, school board seats, city treasurer, city controller, and other local positions, before the national party crumbled.

During its heyday, the Socialist Party did not have much of a presence in the ring counties of Philadelphia, which at that time consisted mostly of small professional class towns or farmland. In the industrial city of Camden, a small Socialist Party published a labor and anti-war newspaper, The Voice of Labor, while Socialists curiously were largely absent from the chemical industry of Wilmington, Delaware.

Prior to World War I, the Socialists focused on building what they called “industrial democracy,” an economy that would be based around worker ownership instead of owner-management ownership. Many militant labor activists were also members of the Socialist Party, as a sort of clearinghouse of radical ideas and connections, even if Socialist Party activity was not their focus.

Election Influences

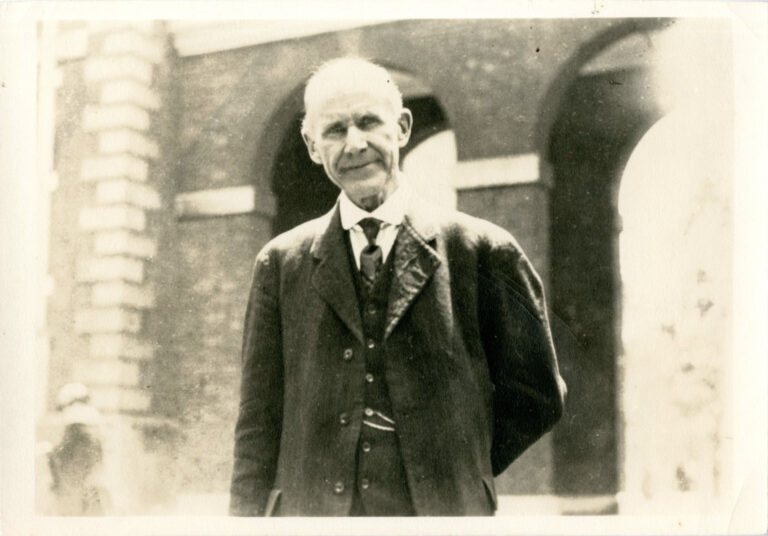

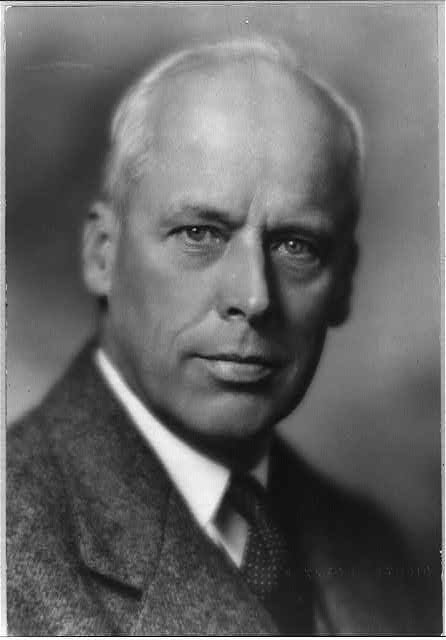

Three presidential elections showed the national influence of the Socialist Party: the 1912 and 1920 Eugene Debs (1855-1926) campaigns, when Debs won 900,390 and 913,664 votes, respectively, and the Norman Thomas (1884-1968) 1932 campaign, when he won 881,951 votes. Those three campaigns also represented good bellwethers of the party’s influence in the greater Philadelphia region, since they represented the three presidential elections of the highest Socialist Party vote totals, both nationally and in the Philadelphia region. In each, Philadelphia County, due to its sheer population size, and Berks County, due to the Socialists’ activist presence in the Reading mills, had the lion’s share of votes for the Socialist Party in the region, and the totals in other counties of the region were minuscule. In the 1912 election, in Philadelphia County, Debs received 19,568 votes (3.9 percent of the total), while in Berks he received 7,272 votes (10.5 percent). In 1912, the vote totals for the rest of the entire Philadelphia region, including the Lehigh Valley, South Jersey river counties, and northern Delaware, was 9,141 (all under 5 percent of the total). In 1920, Debs received 17,484 votes (4.3 percent) in Philadelphia, 5,674 (12.2 percent) in Berks, and 7,166 in the rest of the region (none above 4 percent). In the 1932 election, Norman Thomas garnered 13,038 in Philadelphia (2.1 percent), 15,988 (21.9 percent) in Berks, and 16,571 in the rest of the region(all under 5 percent).

While voting for a Socialist was not the same thing as membership, it did demonstrate the wider influence of the Socialist Party beyond its activist core. The Socialist Party membership was always much smaller than the vote totals, though in general Pennsylvania held the largest, second largest, or third largest state chapters of the party, depending on the year.

Voting was not the only indication of Socialist appeal or activism. In the heavily immigrant Kensington neighborhood, especially among Eastern Europeans, Irish, and Italians and their children, garment and textile workers established themselves as the left wing of the Philadelphia Socialist Party branches, interested far more in direct action industrial unionism than in electoral success. Socialist Party members led the American Federation of Full-Fashion Hosiery Workers as it became an underground secret organization opposing the draconian dictatorship of the emerging women’s clothing corporations by the 1920s. The Kensington Labor Lyceum hosted radical speakers as well as socialist singing societies of the German branch. The Hosiery Workers represented one of two large radical unions in the city, the other being the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) Local 8 on the waterfront. Both pushed for better wages, hours, and benefits, and more control for workers of their own lives from the 1910s through the 1930s.

Anti-War Stance

During World War I the Socialist Party of America, unlike its socialist European counterparts, took an explicitly anti-war stance and strongly opposed the United States mobilization for war. Operating out of its city headquarters/bookstore at 1326 Arch Street, members of the Socialist Party leafletted the city with the pamphlet “Long Live the Constitution of the United States,” urging readers to resist conscription and war during the summer of 1917, which may have contributed to 1,500 of the initial 30,000 Philadelphia draftees not showing up. The party’s Arch Street location was near several military recruiting stations, much to the anger of those recruiters. Moreover, the leafleteers faced mob attacks. In West Philadelphia a running attack of roughly three thousand people chased thirty-four anti-war leafleteers, and another attack took place outside an armory at Forty-First and Mantua Streets.

Police and federal forces launched repressive measures against Socialists in accordance with the Espionage Act of 1917, and thereafter raided a Socialist Party anti-war meeting at Seventh and Dickinson Streets. Finally, on August 28, 1917, police arrested the city’s Socialist Party leadership, including General Secretary Charles T. Schenck (1873-1920). After the war the ensuing free speech case, Schenck v. United States, ended up in the U.S. Supreme Court, where the Socialist Party lost. In Camden, the federal government refused to circulate that publication the Voice of Labor newspaper published during the 1910s because of its anti-war message. The Camden party fell apart after the national party split over the question of aligning with the Soviet Union, although it briefly rebounded during the early years of the Great Depression.

In the aftermath of the war, a nationwide Red Scare and anti-union corporate offensive led to Philadelphia clamping down on both radicals and labor, cementing the city’s reputation as an anti-labor citadel. The Philadelphia Socialists split into a Socialist majority and Communist minority that at times cooperated and at times bitterly opposed each other within the now underground garment unions, like the Hosiery Workers and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. By the Great Depression, they competed for leadership of the Unemployed Councils, although the Socialist Party remained a presence in Kensington with offices on East Allegheny Avenue.

The Socialist Party’s real success was in the city of Reading, in Berks County, sixty miles northwest of Philadelphia. There, the massive Berkshire Knitting Mills became a Socialist recruiting target because of the repressive conditions that workers faced. In elections from 1927 into the next decade, the Socialist Party candidates swept into office, gaining the mayorship, several city council seats, and a host of other positions in Berks County. The Berks Socialists reached their height of electoral success from 1927-36, a period of similar electoral successes in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Supporting Labor Causes in Reading

The Socialist administration in Reading lent support to labor causes, especially the hosiery and pretzel workers unions. Reading also became one of the centers of Socialist Party cultural life, hosting youth conferences, baseball teams, music, theater, the newspaper Labor Advocate, and the Reading Labor College. The Reading Socialists swept the elections of 1936, with a message of good government rather than explicit socialism, but the national Socialist Party fell apart in the late 1930s due to factional fighting between old and new guards. Eventually the old guard left the SPA to form the Social Democratic Federation over the issues of support for the Soviet Union and cooperation with Communists.

With the labor upsurges of the 1930s, former Socialist Party members remained socialists, even as they moved on into other organizations as the national organization collapsed. The Socialist Party branches of Philadelphia and Reading saw the possibilities of a different sort of society, from their influence in unions, brief electoral successes, and campaigns against militarism, even as they faced daunting odds and enemies, from corporate management to both local, state, and national security forces. Many of those Socialists who saw social change through electoral success ended up joining the New Deal Democrats from the late 1930s on.

By the 1940s, remnants of the Socialist Party faded because of its ambiguous position on World War II, neither supporting the war nor actively opposing it in the face of popular support in the United States for the global war against fascism. The few members left after the war later re-formed into the Socialist Party USA, which survived in the early twenty-first century. Although minuscule in numbers compared to the heyday of the Socialist Party, the later organization fielded presidential and statewide candidates for office at various times in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, but with no success.

The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), the largest socialist group in the United States by 2020, also emerged from several splits, mergers, and rebrandings of the Socialist Party of America after the 1950s. Nationally, the DSA grew rapidly after the 2016 and 2020 Bernie Sanders (b. 1941) Democratic Party presidential primary campaigns made “democratic socialism” more widely known and a less threatening philosophy. The DSA was positioned to receive this rapid growth partly because of its name and partly because of its relatively open internal structure. A Philadelphia branch of the DSA became one of the largest in the United States, with regular meetings of a few hundred. The DSA also established branches in Lancaster County, Berks County, and the Lehigh Valley in Pennsylvania, along with a Delaware chapter and a South Jersey chapter.

By 2016, socialism gained renewed interest among left-leaning voters generally, especially after the two Bernie Sanders presidential campaigns where he called himself a democratic socialist and offered a Eugene Debs-like vision of socialism like Scandinavian models of mixed economies. But such interest did not lead to a reconstituted Socialist Party that developed its own slate of candidates and built a separate party movement. By 2022, new groups with no ties to the DSA, such as the “Philly Socialists,” had emerged, but they focused on mutual aid and direct-action political organizing on issues such as tenants’ rights and did not become involved in electoral work. In turn, the DSA sought to affect public policy and gain leadership positions within the Democratic Party by endorsing and supporting democratic socialist candidates running for offices on Democratic Party tickets. Groups like the old Socialist Party of America continued to operate far beyond the lifespan of the original organization, and even, for better or for worse, with many of the same goals of a socialist world as the original SPA. The original Socialist Party of America, through its labor and antiwar work, remained an important note in the history of Philadelphia.

James Robinson, who received his Ph.D. in history from Northeastern University in 2020, is an adjunct instructor at Rutgers University in the Labor Studies Department, and a Philadelphia history tour guide. He has written about links between radicals, labor, and grassroots sports from the 1920s into the 1940s. (Author information current at date of publication.)

Copyright 2023, Rutgers University.